Полная версия

Charlie Bone and the Castle of Mirrors

First published in Great Britain 2005 by Egmont UK Limited

This edition published 2010

by Egmont UK Limited

239 Kensington High Street

London W8 6SA

Text copyright © 2005 Jenny Nimmo

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

ISBN 978 1 4052 2465 9

eBook ISBN 978 1 7803 1205 7

www.egmont.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Egmont is passionate about helping to preserve the world’s remaining ancient forests. We only use paper from legal and sustainable forest sources, so we know where every single tree comes from that goes into every paper that makes up every book.

This book is made from paper certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC), an organisation dedicated to promoting responsible management of forest resources. For more information on the FSC, please visit www.fsc.org. To learn more about Egmont’s sustainable paper policy, please visit www.egmont.co.uk/ethical.

For David, who led me to the castle, with love.

Contents

Cover

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

The endowed children

Prologue

1. A fatal sneeze

2. The phantom horse

3. The boy with paper in his hair

4. Detention for Charlie

5. Billy’s oath

6. Alice Angel

7. The Book of Amadis

8. The white moth

9. A man trapped in glass

10. The jailbird

11. The Passing House

12. Breaking the force-field

13. The battle of oaths and spirits

14. Children of the Queen

15. The enchanted cape

16. The wall of history

17. The black yew

18. Losing the balance

19. Olivia’s talent

20. The warrior

21. The captives’ story

About Egmont Press

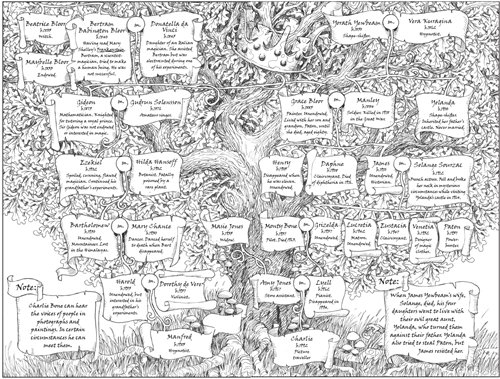

The children of the Red King, called the endowed

Manfred Bloor Son of the headmaster of Bloor’s Academy. A hypnotiser. He is descended from Borlath, eldest son of the Red King. Borlath was a brutal and sadistic tyrant. Asa Pike A were-beast. He is descended from a tribe who lived in the Northern forests and kept strange beasts. Asa can change shape at dusk. Billy Raven Billy can communicate with animals. One of his ancestors conversed with ravens that sat on a gibbet where dead men hung. For this talent he was banished from his village. Lysander Sage Descended from an African wise man. He can call up his spirit ancestors. Tancred Torsson A storm-bringer. His Scandinavian ancestor was named after the thunder god, Thor. Tancred can bring rain, wind, thunder and lightning. Gabriel Silk Gabriel can feel scenes and emotions through the clothes of others. He comes from a line of psychics. Emma Tolly Emma can fly. Her surname derives from the Spanish swordsman from Toledo, whose daughter married the Red King. He is therefore an ancestor to all the endowed children. Charlie Bone Charlie can travel into photographs and paintings. He is descended from the Yewbeams, a family with many magical endowments. Dorcas Loom Dorcas can bewitch items of clothing. Her ancestor, Lola Defarge, knitted a shrivelling shawl whilst enjoying the execution of the Queen of France in 1793. Idith and Inez Branko Telekinetic twins, distantly related to Zelda Dobinsky, who has left Bloor’s Academy. Joshua Tilpin Joshua has magnetism. His origins are, at present, a mystery. Even the Bloors are unsure where he lives. He arrived at their doors alone and introduced himself. His fees are paid through a private bank.

The endowed are all descended from the ten children of the Red King; a magician-king who left Africa in the twelfth century, accompanied by three leopards.

Prologue

The Red King and his queen were riding by the sea. It was that time of year when the wind carries a hint of frost. Evening clouds had begun to appear and where the sun could find a way through the gathering dusk, it struck the sea in bands of startling light.

The king and queen urged their horses home but, all at once, the queen reined in her mount and, in absolute stillness, stared out across the water. The king, following her gaze, beheld an island of astounding beauty. Caught in shafts of sunlight it sparkled with a thousand shades of blue.

‘Oh,’ sighed the queen, in a voice of dread.

‘What is it, my heart?’ asked the king.

In the matter of their children the queen’s intuition was greater than the king’s, and when she saw the island of a thousand blues, it was as if an icy hand had clutched her heart. ‘The children.’ Her voice was hardly more than a whisper.

The king asked his wife which of their nine children concerned her, but the queen couldn’t say. Yet when they returned to the Red Castle and she saw her two sons, Borlath and Amadis, the queen had a terrible forboding. She saw black smoke rising from the blue island, and flames turning the earth to ash. She saw a castle of shining glass appear in a snowstorm, and when her soul’s eye travelled over the glass walls, she saw a boy with hair the colour of snow climb from a well and close his eyes against the death that lay all about him.

‘We must never let our children see that island,’ she told the king. ‘We must never let them tread on that blue, enchanted earth.’

The king made a promise. But in less than a year the queen would be dead, and he, bowed down with grief, would leave the castle and his children. The queen died nine days after giving birth to her tenth child, a girl she named Amoret. A girl whom no one could protect.

A fatal sneeze

At the edge of the city, Bloor’s Academy stood dark and silent under the stars. Tomorrow, three hundred children would climb the steps between two towers, cross the courtyard and crowd through the great oak doors. But for now the old building appeared to be utterly deserted.

And yet, if you had been standing in the garden, on the other side of the school, you could not have failed to notice the strange lights that occasionally flickered from small windows in the roof. And if you had been able to look through one of these windows, you would have seen Ezekiel Bloor, a very old man, manoeuvring his vintage wheel chair into an extraordinary room.

The laboratory, as Ezekiel liked to call it, was a long attic room with wide, dusty floorboards and a ceiling of bare rafters. Assorted tables, covered with bottles, books, herbs, bones and weapons, stood against the walls, while beneath them, a muddle of dusty chests protruded into the room, threatening to trip anyone who might pass their way.

Dried and faded plants hung from the rafters, and pieces of armour, suspended from the broad crossbeams, clunked ominously whenever a draught swept past them. They clunked now as Ezekiel moved across the floor.

The old man’s great-grandson, Manfred, was standing beside a trestle table in the centre of the room. Manfred had grown during the summer holiday, and Ezekiel felt proud that he had chosen to work with him, rather than go off to college like the other sixth-formers. Mind you, despite his height, Manfred had a skinny frame, sallow, blotchy skin and a face that was all bone and hollows.

At this moment his face was twisted into a grimace of concentration as he shuffled a pile of bones across the table in front of him. Above him hung seven gas jets set into an iron wheel, their bluish flames emitting a faint purr. When he saw his great-grandfather, Manfred gave a sigh of irritation and exclaimed, ‘It’s beyond me. I hate puzzles.’

‘It’s not a puzzle,’ snapped Ezekiel. ‘Those are the bones of Hamaran, a warhorse of exceptional strength and courage.’

‘So what? How are a few measly bones going to bring your ancestor back to life?’ Manfred directed a disdainful glance at Ezekiel, who instantly lowered his gaze. He didn’t want to be hypnotised by his own great-grandson.

Keeping his eyes fixed on the bones, the old man brought his wheelchair closer to the table. Ezekiel Bloor was one hundred and one years old, but other men of that age could look considerably better preserved. Ezekiel’s face was little more than a skull. His remaining teeth were cracked and blackened, and a few thin strands of white hair hung from beneath a black velvet cap. But his eyes were still full of life; black and glittering, they darted about with a savage intensity.

‘We have enough,’ said the old man, indicating the other objects on the table: a suit of chain mail, a helmet, a black fur cape and a gold cloak pin. ‘They’re Borlath’s. My grandfather found them in the castle, wrapped in leather inside the tomb. The skeleton was gone, more’s the pity. Rats probably.’ He stroked the black fur almost fondly.

Borlath had been Ezekiel’s hero ever since he was a boy. Stories of his warlike ancestor had fired his imagination until he came to believe that Borlath could solve all his problems. Lately, he had dreamt that Borlath would sweep him out of his wheelchair and together they would terrorise the city. Then Charlie Bone and his detestable uncle would have to look out.

‘What about electricity for the – you know – moment of life? There isn’t any in here.’ Manfred looked up at the gas jets.

‘Oh that!’ Ezekiel waved his hand dismissively. He wheeled himself to another table and picked up a small tin with two prongs extending from the top. He turned a handle in the side of the tin and a blue spark leapt between the prongs. ‘Voila! Electricity!’ he gleefully announced. ‘Now get on with it. The children will be back tomorrow, and we don’t want any of them getting in the way of our little experiment.’

‘Especially Charlie Bone,’ Manfred grunted.

‘Huh! Charlie Bone!’ Ezekiel almost spat the name. ‘His grandmother said he’d be a help, but he’s the reverse. I thought I’d almost got him on my side last term, but then he had to go whining on about his lost father and blaming me.’

‘He wasn’t wrong there,’ said Manfred, almost to himself.

‘Think what we could do with that talent of his,’ went on Ezekiel. ‘He looks into a picture and bingo he’s there, talking to people long dead. What I wouldn’t give . . .’ Ezekiel shook his head. ‘He’s got the blood of that infernal Welsh magician. And the wand.’

‘I have plans for that,’ said Manfred softly. ‘It’ll be mine soon, just you wait.’

‘Indeed?’ Ezekiel chuckled. He began to propel himself away while his great-grandson concentrated on the delicate job of bone-gluing.

As Ezekiel moved into the deep shadows at the far end of the room, his thoughts turned to Billy Raven, the white-haired orphan who used to spy on Charlie Bone. Billy had become rebellious of late. He’d refused to tell Ezekiel what Charlie and his friends were up to. As a result, Ezekiel and the Bloors were in danger of losing control of all the endowed children in the school. Something would have to be done.

‘Parents,’ Ezekiel said to himself. ‘I’ll have to get Billy adopted. I promised I’d find the orphan some parents and I never did. He’s given up on me. Well, Billy shall have his nice, kind parents.’

‘Not too kind,’ said Manfred, who had overheard.

‘Never fear. I’ve got just the couple. I don’t know why I didn’t think of them before.’ Ezekiel turned his head expectantly. ‘Ah, we’re about to get assistance.’

A distant patter of footsteps could be heard; a few seconds later the door opened and three women walked into the room. The first was the oldest. Her iron-grey hair was piled atop her head like a giant bun; her clothes were black and so were her eyes. Lucretia Yewbeam was the school matron and Charlie Bone’s great-aunt. ‘I’ve brought my sisters,’ she told Ezekiel. ‘You said you needed help.’

‘And where’s the fourth?’ asked Ezekiel. ‘Where’s Grizelda?’

‘She’s best left out of things for now,’ said Eustacia, the second sister. ‘After all, she’s got to live with our wretched brother – and the boy. She might blab – accidentally, of course.’

Eustacia, a clairvoyant, walked over to the table. Her grey hair still held threads of black, but in most other respects she resembled her older sister. Her small eyes darted over the objects on the table and she gave a crooked smile. ‘So, that’s what you’re up to, you old devil. Who is he?’

‘My ancestor, Borlath,’ Ezekiel replied. ‘Greatest of all the Red King’s children. Most magnificent, powerful and wise.’

‘Most vile and bloodthirsty, would be more accurate,’ said the third sister, dumping a large leather bag on the table. Her greasy hair hung over her shoulders in sooty swathes and dark shadows ringed her coal-black eyes. Compared with her sisters she looked a mess. Her long coat was a size too large for her, and the greyish blouse beneath looked badly in need of a wash. No one would have guessed that this bedraggled creature had once been a proud and immaculately dressed woman.

‘Venetia’s been waiting for something like this,’ said Eustacia. ‘Ever since that hateful Charlie Bone burnt her house down.’

‘I thought your brother did that,’ put in Manfred.

‘So he did,’ snarled Venetia, ‘but Charlie was responsible, the little worm. I want him snuffed out. I want him gibbering with fright, tortured, tormented – dead.’

‘Calm down, Venetia.’ Ezekiel spun quickly to her side. ‘We don’t want to lose the boy entirely.’

‘Why? What use is he? Can you imagine what it’s like to lose everything? To see your possessions – the work of a lifetime – go up in smoke?’

Ezekiel whacked the table with his cane. ‘Don’t be so pathetic, woman. Charlie can be used. I can force him to carry me into the past. I could change history. Think of that!’

‘You can’t change history, Great-grandpa,’ Manfred said flatly.

‘How do you know?’ barked Ezekiel. ‘No one’s tried.’

An awkward silence followed. No one dared to suggest that it had probably been tried several times, without success. Venetia chewed her lip, still thinking of revenge. She could wait, but one day she would find a way to finish Charlie Bone – permanently.

Lucretia broke the silence by asking, ‘Why the horse?’

‘Because I’ve got the bones,’ snapped Ezekiel. ‘This horse, Hamaran,’ he nodded at the bones, ‘was a magnificent creature, by all accounts. And a mounted man can be very threatening, don’t you agree?’

The others muttered an assent.

‘The boy will be terrified,’ Ezekiel went on gleefully. ‘He’ll do anything we ask.’

Venetia said, ‘And how are you going to control this freak?’

Ezekiel had been hoping that no one would ask him this, because he didn’t have a satisfactory answer, yet. ‘He’s my ancestor,’ he said with a confident grin. ‘Why wouldn’t he help me? But first things first. Let’s get it up and running, as it were. Ha! Ha!’

While Lucretia sat on a moth-eaten armchair her sisters unpacked the leather bag. Phials of liquid began to appear on the table; silver spoons, bags of herbs, small, twinkling pieces of quartz, a black marble pestle and mortar, and five candles. Ezekiel watched the proceedings with hungry eyes.

An hour later the leg bones of a galloping horse had been arranged on the table. The chain mail glistened with a foul-smelling liquid and the fur cloak had been covered with tiny seeds.

The five candles cast leaping shadows on the wall. One had been placed above the helmet, one at the end of each of the chain-mail sleeves, and the last two stood in place of the horse’s missing front hooves.

Venetia had enjoyed the work in spite of herself. It was good to get her teeth into something destructive again. As she caressed the black fur, tiny flames crackled at the tips of her fingers. ‘Are we ready, then?’ she asked.

‘Not quite.’ With a cunning smile Ezekiel put his hand beneath the rug on his lap and produced a small golden casket. In the centre of the jewelled lid a cluster of rubies, shaped like a heart, shone out in the dim room with a dazzling brilliance. ‘The heart,’ said Ezekiel, his voice a deep-throated gurgle. ‘Asa, the beast-boy, found it in the ruin. He was out there digging, as is his wretched habit, and he found a gravestone marked with a B. He dug further and found this,’ he tapped the casket, ‘buried deep beneath the stone.’

From her chair in the shadows, Lucretia asked, ‘Why wasn’t it in the tomb?’

‘Why? Why?’ Ezekiel gave way to a bout of unpleasant, bronchial coughing. ‘Secrecy, perhaps. But it’s his. I know it. Borlath was the only one of the king’s children with the initial B.’ He opened the casket.

‘Aaaaah!’ Eustacia stepped away from the table, for inside the casket lay a small heart-shaped leather pouch that did, indeed, appear to contain – something.

‘See? A heart,’ said Ezekiel triumphantly. ‘Now, let’s get on with it.’ Scooping the pouch from its casket, he placed it on the suit of armour, just left of centre, where he judged a heart might lie. Then he uncoiled a wire from his electric box and wrapped the end once, twice, three times around the pouch.

An expectant hush descended on the room as the old man began to turn the handle of the silver box. Faster and faster. His crooked hand became a flying blur, his black eyes burned with excitement. A spark leapt between the steel prongs and travelled down the wire to Borlath’s heart. Ezekiel emitted a croak of triumph and his hand was still.

The three sisters were tempted to exclaim with rapture, but they knew that silence was essential at such a moment. The bones of Hamaran were beginning to move.

Ezekiel and the Yewbeams were watching the table so intently, they failed to notice Manfred pull out a handkerchief and press it to his nose. His face turned bright pink as he struggled to suppress a sneeze. It was no use.

‘ATISHOO!’

Ezekiel recoiled as if from a blow. He covered his ears and rasped, ‘No,’ as Manfred tried to hold back yet another sneeze. The sisters watched in horror as the young man screwed up his face, and,

‘ATISHOO!’

The bones stopped moving. Vile, black vapour rose from the fur and the chain mail writhed under the smouldering pouch.

‘ATISHOO!’

There was a thunderous bang and a reeking pall of smoke filled the room. As the onlookers choked and spluttered, a huge form lifted from the table and vanished into the billowing black clouds. Hidden under one of the tables at the far end of the room, a short, fat dog trembled and closed his eyes.

A second violent bang shook the whole room, and Lucretia cried, ‘What happened?’

‘That ruddy idiot sneezed,’ shrieked Ezekiel.

‘Sorry, sorry. Couldn’t help it,’ whined Manfred. ‘It was the dust.’

‘Not good enough,’ scolded Venetia. ‘You should have taken your wretched nose outside. The whole thing’s ruined. A waste of time.’

‘Maybe not,’ Eustacia broke in. ‘Look at the table. The bones have gone.’

The smoke was clearing rapidly due to a sudden rush of cold air, and they all saw that the bones of Hamaran had, indeed, vanished. But Borlath’s armour, his helmet, cloak and gold pin, still lay where they were, rather the worse for the spell they had been subjected to.

‘Damn!’ cried Ezekiel. He thumped the table with his fist and the scorched garments shuddered. ‘It didn’t work.’

‘My part did,’ said Manfred. ‘The horse is out there.’ He pointed to a gaping hole in the wall.

‘Dogs’ teeth!’ yelled Ezekiel. ‘My laboratory’s wrecked, and there’s a warhorse on the loose.’

‘A warhorse with a tyrant’s heart,’ said Venetia. ‘See, it’s gone!’

Where the heart had lain, there was now only a scorched black hole in the smouldering armour.

‘What does it mean?’ asked Manfred, in a hushed voice. Ezekiel stroked his long nose. ‘It means that all’s not lost. But I’ll need help. I think I’ll call on a friend of mine, someone with a score to settle.’

Everyone looked at him, waiting for a name, but the old man was not ready to enlighten them.

‘A warhorse could be very useful,’ said Venetia thoughtfully, ‘providing one could ride it.’

They all stared at the empty space left by the bones, as though willing it to speak, and then Manfred said, ‘Billy Raven’s good with animals.’

In a long dormitory, three floors beneath Ezekiel’s attic, Billy Raven woke up, suddenly afraid. He turned to the window for a reassuring glimpse of the moon and saw a white horse sail through ragged clouds – and disappear.

The phantom horse

On the first day of the autumn term, Charlie Bone dashed down to breakfast with a comb sticking out of his hair.

‘What do you think you look like?’ said Grandma Bone from her seat beside the stove.

‘A dinosaur?’ Charlie suggested. ‘I pulled and pulled but my comb wouldn’t come out.’

‘Hair like a hedge,’ grunted his bony grand mother. ‘Smarten yourself up, boy. They don’t like untidiness at Bloor’s Academy.’

‘Come here, pet.’ Charlie’s other, more tender-hearted, grandmother put down her cup of tea and tugged at the comb. Out it came with a clump of Charlie’s hair.

‘Maisie! Ouch!’ cried Charlie.

‘Sorry, pet,’ said Maisie. ‘But it had to be done.’

‘OK.’ Charlie rubbed his sore head. He sat at the kitchen table and poured himself a bowl of cereal.

‘You’re late. You’ll miss the school bus,’ said Grandma Bone. ‘Dr Bloor’s a stickler for punctuality.’

Charlie put a spoonful of cereal into his mouth and said, ‘So what?’

‘Don’t speak with your mouth full,’ said Grandma Bone.

‘Leave him alone, Grizelda,’ said Maisie. ‘He’s got to have a good breakfast. He probably won’t have a decent meal for another five days.’

Grandma Bone snorted and bit into a banana. She hadn’t smiled for three months; not since her sister Venetia’s house had burned down.

Charlie gulped back a mug of tea, flung on his jacket and leapt upstairs to fetch his school bags.

‘Cape!’ he said to himself, remembering it was still hanging in the wardrobe. He pulled out the cape and a small photograph fluttered to the floor. ‘Benjamin,’ he smiled picking it up. ‘Where are you?’