Полная версия

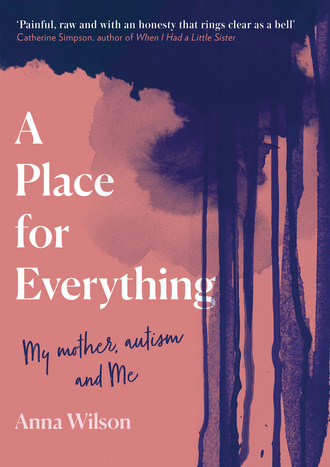

A Place for Everything

Oh, my light and my life. What would Mum be without Dad?

Thirteen

‘Anti-depressants such as fluoxetine (Prozac) have been used to reduce repetitive behaviour. But there are concerns about the use of these drugs … because of the side effects (such as agitation) … anti-psychotic drugs … have also been used as a treatment for irritability and hyperactivity in autism or Asperger Syndrome but again carry risks of side effects (such as mood swings).’ 13

Dad and I are now reunited with Mum, who is being seen by a consultant psychiatrist. I can’t help noticing how young and handsome he is. What am I thinking? I look away, telling myself to get a grip. It’s just such a relief to look at something beautiful.

The consultant takes us through a new regime of drugs and explains that citalopram, the anti-depressant that Mum was prescribed, should be taken in the morning, not at night as her previous psychiatrist had instructed.

‘It has the side-effect of waking you up,’ he explains, ‘hence your mother’s agitation at night. I have already explained this to her.’

I look at Mum, who is breathing shallowly and staring ahead. I can’t believe that she has taken in a word of what the doctor has told her.

‘She should also stick with the citalopram for at least six months,’ he is saying, ‘and not give up after one week as she has been previously advised.’

My head fills with red-hot curses. That bloody psychiatrist! Signing her off with an incorrect prescription! That idiot! That bastard!

I say nothing, however. I try to focus on what we’re being told, while repeating to myself over and over, Please say you’ll keep her in hospital. Please don’t send her home with us. Please. Please.

‘I’m going to give Gillian olanzapine for her psychosis,’ the psychiatrist is saying.

Psychosis! He has said the word. He sees this for what it is. At last. Not a urinary tract infection, then? Surely psychosis is serious enough to keep Mum in?

I know, even as I hope this, that it won’t happen. We are in A&E. You only get admitted if it’s a case of life or death. Mum has us. And she’s not dying.

‘A mental health team from Maidstone will come to the house every day to monitor her progress,’ the doctor says. ‘They’ll be able to keep an eye on how you’re coping as well, Martin,’ he tells Dad.

Mum says nothing. The psychiatrist is no longer looking at or speaking to her. He is directing all his comments to me and Dad. It is clear we are responsible. We always have been. It was folly to think that anyone else would take the baton from us. There is no magic wand. No miracle cure. We have to take her home with us. But, still – a team! A whole team, dedicated to Mum!

Dad looks hopeful. ‘That’s wonderful. Thank you,’ he says.

We’ll have to wait for them to visit, though. And in the meantime we still have an extremely distressed woman on our hands. Mum has found the ordeal of the tests and the questioning too much. On the way back to the car she is agitated again, trotting, whooping, panting, drawing unwanted stares as she did when we arrived. It’s only two o’clock and we still have the rest of this day to get through.

Mum is not allowed to start some of the new drugs until 9 p.m. When we get home, Dad and I resort to what all stressed-out parents do when caring for a wired and noisy child – we put the telly on. We find a documentary about British sketch shows, which includes clips from The Two Ronnies, Monty Python, Not the Nine O’Clock News, Fry and Laurie. I know Dad is thinking what I’m thinking; how, thirty years ago, we sat on the same sofa and watched these same shows together, Dad and I hooting with laughter, Mum not understanding the humour and having to have the jokes explained. No one is laughing now.

At long last it’s time for the life-saving pills. I’m not letting myself think of the implication of chucking so many highly potent chemicals down my mother’s throat. I just cling to the idea of her falling asleep.

Dad and I tuck her into bed, and I send Dad downstairs for a glass of wine and a break as I sit with Mum, stroking her hand. I find myself wanting to sing the only song she ever sang to me when I was small: ‘Golden Slumbers’. I contemplate reading to her. She didn’t like reading us bedtime stories. She didn’t really like stories – didn’t see the point of them. ‘I prefer facts,’ she used to say. Dad was the storyteller, the crooner, recounting tales by heart, remembering the words to every Beatles song, every folk song and nursery rhyme and poem.

Before I can test the tune of the lullaby to see if I can manage to sing without crying, Mum is asleep, snoring gently. I leave her to go back downstairs and sink a glass of wine with Dad. Our own drug of choice.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.