Полная версия

The Child of the Sun

ERZEUGT DURCH JUTOH - BITTE REGISTRIEREN SIE SICH, UM DIESE ZEILE ZU ENTFERNEN

ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart

ERZEUGT DURCH JUTOH - BITTE REGISTRIEREN SIE SICH, UM DIESE ZEILE ZU ENTFERNEN

Contents

The Writing Queens of Romania, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) and Marie

Queen Consorts and Writers – a Romanian Phenomenon

Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva): “How I came to take the name of Carmen Sylva as my nom de plume“

Album: Queen Elisabeth, Portraits and Books

Queen Marie: “So I began to write fairy-tales”

Album: Queen Marie, Portraits and Books

The Ideal Sovereign in the Vision of the Writing Queens of Romania, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) and Marie

Bibliography

Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva): Published Works (Selection)

Queen Marie: Published Works (Selection)

Further Bibliography

Selected Fairy Tales

Queen Elisabeth of Romania (Carmen Sylva)

The Child of the Sun

The Treasure Seekers

Vârful cu Dor (The Peak of Yearning)

The Cave of Ialomitza

Furnica (The Anthill)

The Witch’s Stronghold (Cetatea Babei)

The Caraiman

The Serpent-Isle

Râul Doamnei (The River of the Princess)

The Story of a Helpful Queen

My Kaleidoscope

“Stand! Who Goes There?”

Queen Marie of Romania

The Sun-Child

Conu Ilie’s Rose Tree

Baba Alba

The Snake Island

Parintele Simeon’s Wonder Book. A Very Moral Story

A Christmas Tale

The Magic Doll of Romania (fragments)

Selected Essays about Romania

Queen Elisabeth of Romania (Carmen Sylva): Bucharest

Queen Marie of Romania: My Country (fragments)

Queen Marie of Romania: The Country That I Love. An Exile’s Memories (fragments)

“Why This Book Was Written” (Preface)

Jassy

Bran Castle

ERZEUGT DURCH JUTOH - BITTE REGISTRIEREN SIE SICH, UM DIESE ZEILE ZU ENTFERNEN

The Writing Queens of Romania, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) and Marie

Queen Consorts and Writers – a Romanian Phenomenon

The history of the monarchy in Romania and of its four kings would be incomplete without the story of the queen consorts, who seem to have been even more fascinating personalities than the kings. The first two queen consorts, Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) and Marie of Romania, became famous as writers during their lifetime. They both wrote in their mother tongues, Elisabeth in German and Marie in English, and published many of their books, not only in Romania, but also abroad, thus reaching a widespread readership, worldwide publicity, and literary recognition.

Queen Elisabeth of Romania, born on 29 December 1843 in Neuwied, was the eldest child of Prince Hermann of Wied and his wife Marie, born Princess of Nassau. She had received an intense education and was already 26 years old when she married Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen in November 1869, who had become the elected Prince Carol I of Romania in 1866. After the Russian-Turkish war in 1878, when Prince Carol won Independence for his country, Romania became a kingdom and Carol I and Elisabeth the first royal couple of the land. Unfortunately for the royal couple, their first and only child, Princess Marie, died very young, in 1873, and they did not have any other children. This was especially hard for Elisabeth, who suffered because she could not offer an heir to the Kingdom Romania. In 1878, she started her literary activity with a volume of translations of Romanian contemporary poetry into German. In 1880, she chose the pen name Carmen Sylva for her writings. She published a variety of writings in almost all literary genres, written mostly in German: poems, fairy tales, novels, stage plays, essays, and aphorisms (in French and German). Many of her writings soon appeared in translations into Romanian, French, and English. In 1882/1883 Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva) published the first volume of fairy tales and legends connected with the name of the Pelesh Castle in Sinaia. The castle was built by King Carol I of Romania and inaugurated in 1883, and it was named after the river close-by who also gave the tales their name: Pelesch-Märchen (Tales of the Pelesh). The book was published in Romania and Germany, and some of its tales were later published in English translation in the volume Legends from River & Mountain (1896).

The reign of King Carol I ended with his death on 10 October 1914, after 48 years, the longest one of a sovereign in Romania. Queen Elisabeth died on 2 March 1916.

Queen Marie of Romania was born in Eastwell Park in Great Britain on 29 October 1875, as the eldest daughter of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and (since 1893) Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the second son of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and Duchess Marie, born Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, the only daughter of Emperor Alexander II of Russia. She spent a happy childhood in Kent, Malta, and Coburg and married in January 1893, aged 17, the Crown Prince of Romania, Ferdinand, the second son of Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen and nephew of King Carol I of Romania. In October 1893, she gave birth to the next heir of the Romanian dynasty, Prince Carol who would later become King Carol II of Romania.

As crown princess, she began to write fiction, being encouraged by Queen Elisabeth of Romania (Carmen Sylva), who translated some of her stories into German and wrote a preface to Marie‘s fairy tale The Lily of Life (1913). After the death of King Carol in 1914, Ferdinand and Marie became the second royal couple of Romania. During the First World War it was mainly Queen Marie who appeared in public as an author of books, essays, and articles which were meant to promote the national cause of Romania at war while it was partly under the occupation of German and Bulgarian troops. After the war, Queen Marie travelled to Paris and remained there during the Peace Conference held in Versailles in July 1919, in order to campaign for the unification of the provinces Transylvania, Bessarabia, and Bukovina with the Old Kingdom of Romania, all territories with a majority of Romanian population. The enlargement of Romania being recognized in Versailles, King Ferdinand and Queen Marie of Romania thus became the royal couple of Greater Romania. The reign of King Ferdinand ended with his death on 20 July 1927, after only 13 years; Queen Marie outlived Ferdinand for 11 years, and she died on 18 July 1938.

Both first royal couples – King Carol I and Queen Elisabeth as well as King Ferdinand and Queen Marie – are buried in the Cathedral of Curtea de Argeş.

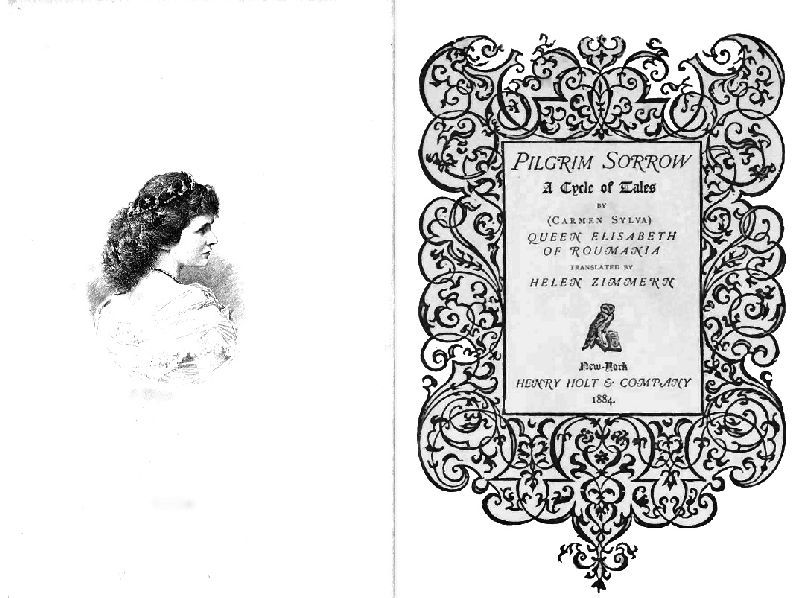

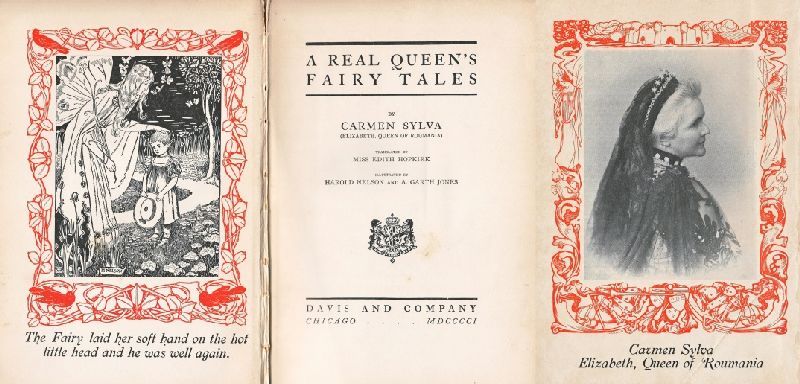

Queen Elisabeth and Crown Princess Marie of Romania had both published some of their fairy tales and fantasy novels in English editions in the United Kingdom and the United States around the year 1900. While the crown princess wrote in English, the German writings of Queen Elisabeth were translated into English. Both queens mentioned their royal status on the titles of their books: Pilgrim Sorrow. A Cycle of Tales by (Carmen Sylva) Queen Elisabeth of Roumania (New York, 1884), Golden Thoughts of Carmen Sylva Queen of Roumania (London and New York, 1900), A Real Queen’s Fairy Tales by Carmen Sylva (Elizabeth, Queen of Roumania) (Chicago, 1901), A Real Queen’s Fairy Book by Carmen Sylva (Queen of Roumania) (London, 1901), The Lily of Life. A Tale by Crown Princess of Roumania with a preface by Carmen Sylva (London, New York, Toronto, 1913). After the death of King Carol I, Queen Marie continued to publish her fairy tales, novels, and children’s books in the USA and the UK calling herself simply „The Queen of Romania”: The Dreamer of Dreams by The Queen of Roumania (London, New York, Toronto, 1915) and The Queen of Roumania’s Fairy Book (New York, ca. 1923).

Besides their fairy tales, in which the queen writers combine fictional tales with promoting the Romanian landscape and popular traditions, they also published some autobiographical tales and essays about their Kingdom. From the writings of Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva), which also appeared in English translation, the essays and memoirs are worth mentioning: Bucharest (1893), My Reminiscences of War (1904), How I Spent My 60th Birthday (1904), and From Memory’s Shrine (1911). The best known book from Queen Marie’s English editions would be her memoires: The Story of My Life (1934-1935). Further interesting autobiographical writings of Queen Marie about Romania are the books: My Country (1916) and The Country That I Love, (1925). Finally, her children’s book The Magic Doll of Romania. A Wonder Story in Which East and West Do Meet (1929), written especially for American children, is an interesting combination of fairy tale with autobiographical aspects and publicity for Romania by the time it was a Kingdom under the reign of King Ferdinand and Queen Marie.

Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva): “How I came to take the name of Carmen Sylva as my nom de plume“

Queen Elisabeth explains her pen name in an autobiographical tale for children, published in German in the volume Märchen einer Königin (1901) and in English translation in A Real Queen’s Fairy Tales1 (1901):

I have very often been asked how I came to take the name of Carmen Sylva as my nom de plume. […] I passed my childhood in the forest amidst the loveliest beech forest trees standing far higher than the castle, and growing so close up to it that their shadows fell across the threshold. […] Now it can be imagined how much the forest told me, especially on my solitary walks. The storm-wind was a special friend of mine. When it made the oaks and the beeches sway and groan, sawing the branches asunder till they came crashing down, then I would tie my little hood over my brown hair, and with my two big St. Bernard dogs by my side, I would race through the forest, avoiding all the beaten tracks, and listen to its voices; for the forest told me stories all the time.

The forest sang the songs to me, which I wrote down afterward at home, but which I never showed to anyone. It was our secret – the woods and mine. We kept it to ourselves. No one else should know the songs we sang together, we two, for no one else would understand them as we did. But the songs poured from my pen, and if my thoughts do but go back to the woods, again they come, like a far-off greeting from my childhood’s days.

How often have I flung my arms round a tree to embrace it, and kissed the rough bark, for if my fellow-creatures thought me too wild and impetuous, the forest never did. The trees never complained that my young arms hugged them too violently, or that I was too noisy when I sang my songs at the top of my voice. For I could never think my songs to myself unsung. I sang them over and over again, hundreds of times, and always to new melodies. […]

I have lovely woods, also, here in Romania, but fir-trees are mixed with the other trees, and there are no lofty, spacious beech avenues, like the aisles of a Gothic cathedral, as in my woods beside the Rhine. And quite a different set of wild animals – bears, lynxes, chamois, eagles, and moor-fowl – inhabit these forests. It is almost another world here, but very beautiful, nevertheless. […]

As a child I always thought I was not so good as the others, and not so well loved, because I was less lovable. And how I prayed that l might become better and worthier of being loved, and that God would also grant me the power in some way or other to set forth his praises, because my heart was always overflowing with thankfulness to see the world so beautiful, and to feel myself so full of youthful strength. And there in secret he planted in my breast the power of poetic song. But at first I did not understand rightly how glorious a gift God had given to me. I did not value it at all – I fancied every one could do just the same, if they only cared to try. And when I grew older and saw that it was really a gift bestowed upon me from on High, then I became still more afraid to speak of it, lest I should be thought vain and boastful. I did not even dare to learn the rules of my art, nor to correct mistakes that I had made; I felt as if that would be scarcely honest and sincere. When I married, I had already written a large volume of poems, and had tried my hand as well at the drama and at prose, writing my first story at eleven years of age and my first play at fourteen. But I knew quite well that it was all very poor stuff. Not till I was five and thirty did I let anything be printed, and that was only because so many people took the pains to copy verses from my scrap-book that I wanted to spare them the trouble and simplify matters. After a time I began to search for a name under which I could hide myself, so that nobody might ever suspect who I really was.

One morning I said to the doctor: “I want a very pretty, poetic name to publish under, and now that I am in Romania, and belong to a Latin people, it must be a Latin name. Yet it must have something in it to recall the land I came from. How do you say 'forest' in Latin?’

“The forest is called silva – or, as some write it, sylva.”

“That is charming! And what do you call a bird?”

„Avis.“

“I do not like that. It is not pretty. What’s the word for a short poem or song?”

“In Latin that is carmen.”

I clapped my hands together. “I have my name. In German I am Waldgesang, the song of the woods, and in Latin that is carmen sylvae. But sylvae does not sound like a real name, so we must take a trifling liberty with it and I will be called Carmen Sylva.”

Since then I resemble the linden tree more and more. Many songsters come and take shelter under my branches and sing beneath my roof, and the bees are countless who work in my house. For it is no home for idlers; work is going on there from early morn till evening, my bees are always flying in and out. But I myself begin work earlier than any of them, for winter and summer I am up before the sun and at my work.

Woodsong, Carmen Sylva, is my name – the name under which I hid myself for so long, and if today I come forth from that shelter that was like the broad leaves of the silver-linden spread over me, it is because so many friends, and especially dear children, have asked it of me, and because I have white hair now and would so gladly be a grandmother if only God had granted me that blessing. I must e’en be all children’s grandmother, and never refuse them anything they ask. The Woodsong is indeed for all children if they will only listen to it, and it will gladden them all alike, whether they be rich or poor, well cared for or in want, whether they go barefoot or wear boots lined with costly fur. The Woodsong loves all alike that come to her, and pours out her whole soul for their delight. And her white hair is like the silver lining of the linden leaves – it gives a bright sheen to thoughts that were otherwise too grave, and she desires that within her shadow it may always be light.

What is it then to be a queen, if it is not like the silver linden tree to cast a protecting shadow over the world’s sweetest songbirds, to offer shelter and refuge to all those whose finely wrought workmanship vies with the spider’s skill; to be the providence of the industrious bees lest they perish in the winter? If all this be done, then indeed may life’s autumn be as sunny as that golden foliage which seems to have retained the whole summer's warmth and light to radiate it forth again.

But it is harder for poor Carmen Sylva than for any other silver-linden. For God had once given her the loveliest song of all, and then he took it away from her again, because he wanted it in his own heaven. That song was her only child, a little girl whose name was Marie, but who called herself Itty when she was so small that she could not say little, and so the name Itty clung to her. She glided about like a little fairy, as if she had wings, during the whole of her short life, she said the sweetest things, she would throw herself on the earth to kiss the sunbeams. She loved the trees, and the flowers, and the water; she danced along the steepest mountain paths as if there were no danger, no precipice below. And if ever I were sad, she sprang up behind me in the big armchair, and turned my face round to her and looked in my eyes to ask: “Are you not happy, mama?”

But God called her back to heaven because the little angel was missing there, which he had lent for a short time to earth. And it seemed to the poor linden tree as if it stood there desolate, and as if there were no voices to be heard in its branches, and as if the sky had suddenly darkened overhead, and the sun gave no more warmth.

But years afterward, all at once a soft murmur penetrated the sorrowing tree and stirred it to the very core. And then the sky grew bright again, and the birds sang once more, and the dried blossoms filled with honey, for it was the voice of Song and Story, the nearest approach this world can offer for the voice of Itty – consoling and gladdening the heart by endeavoring to give comfort and joy to others.

***

And now, dear children, I bid you farewell for the present. Next year I may have another volume for you. In the meantime I hope you will tell me which of these tales you like best and perhaps I will write sequels to some of them.

Album: Queen Elisabeth, Portraits and Books

Queen Elisabeth of Romania, the poet Carmen Sylva, ca. 1883.

Queen Elisabeth in Romanian costume, ca. 1883-1886.

Princess Elisabeth with her daughter Maria, ca. 1873.

Queen Elisabeth, ca. 1883.

Queen Elisabeth, coronation photography, 1881.

Queen Elisabeth, ca. 1896, old postcard.

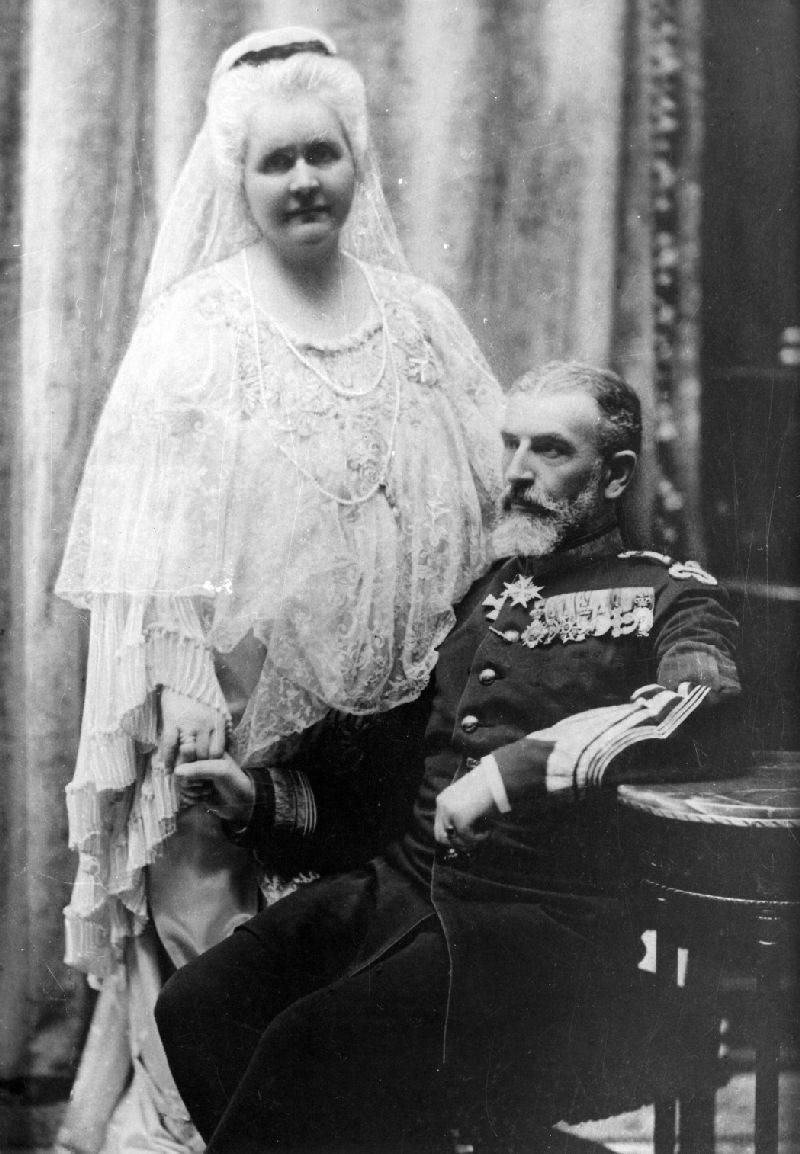

King Carol I and Queen Elisabeth, ca. 1909, old postcard.

King Carol I and Queen Elisabeth, ca. 1913.

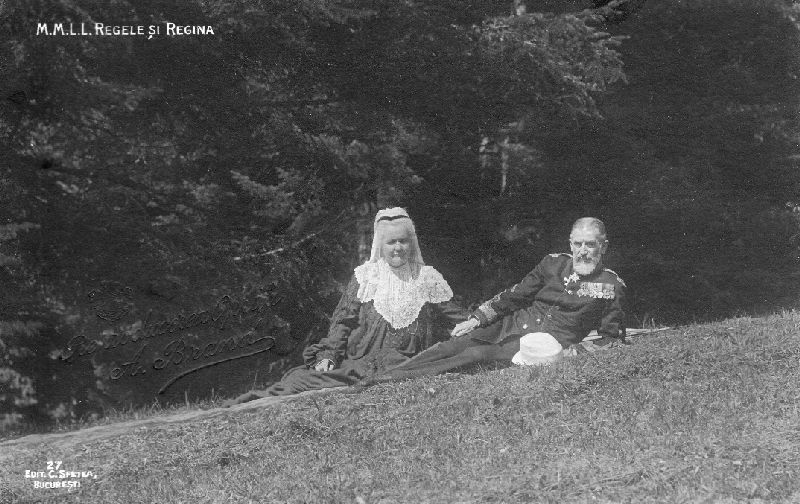

King Carol I and Queen Elisabeth at Sinaia, ca. 1913, old postcard.

Queen Elisabeth photographed by Crown Princess Marie on the Serpent-Isle, ca. 1910.

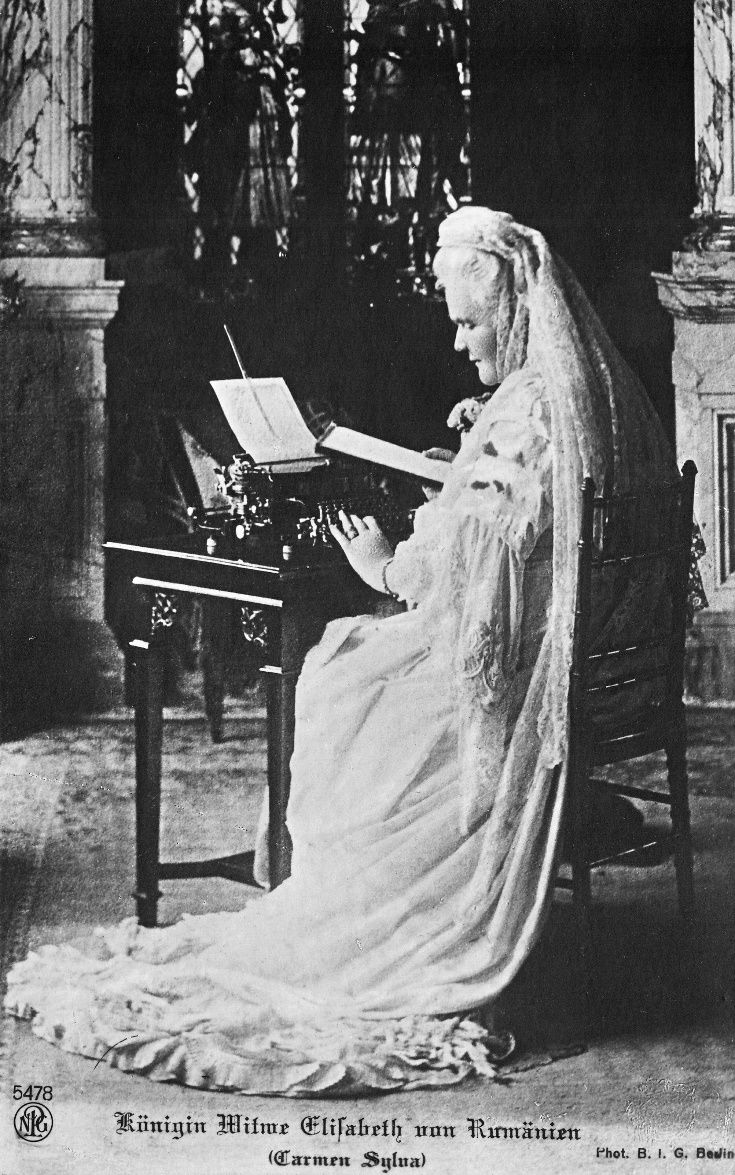

Queen Dowager Elisabeth, ca. 1914-1915, old postcard.

„Pilgrim Sorrow. A Cycle of Tales” (New York, 1884),

American English edition of the book “Leidens Erdengang” (German edition, 1882).

With a portrait of Queen Elisabeth on the frontispiece.

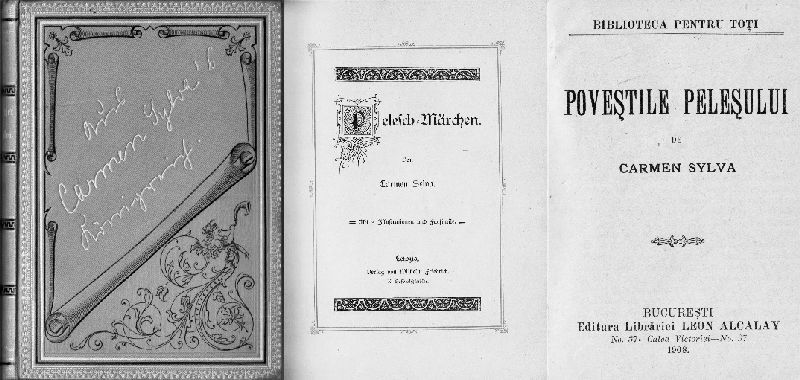

”Pelesch-Märchen” (Tales of the Pelesh) by Carmen Sylva

(cover and title page of the 1st German edition, 1883),

and “Poveştile Peleşului” (title page of a Romanian edition from 1908).

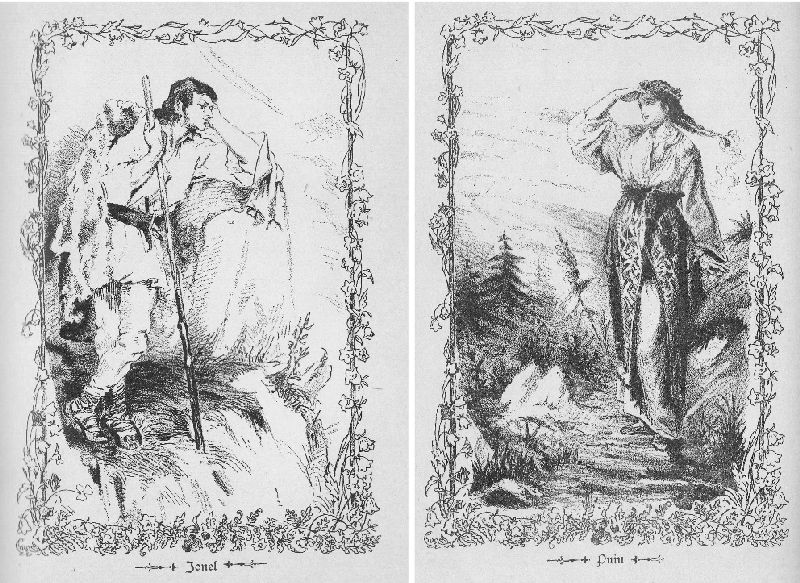

Illustrations of Romanian peasants in “Pelesch-Märchen”

(Tales of the Pelesh, 1st German edition, 1883).

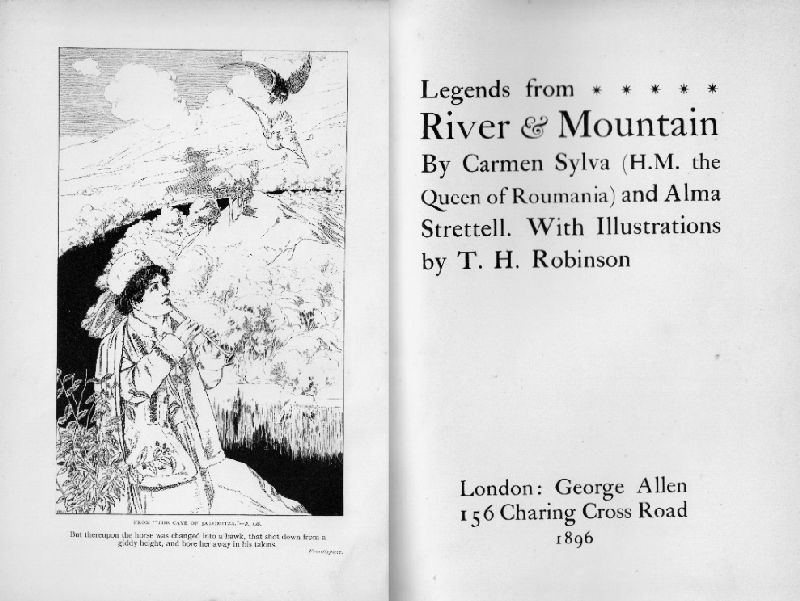

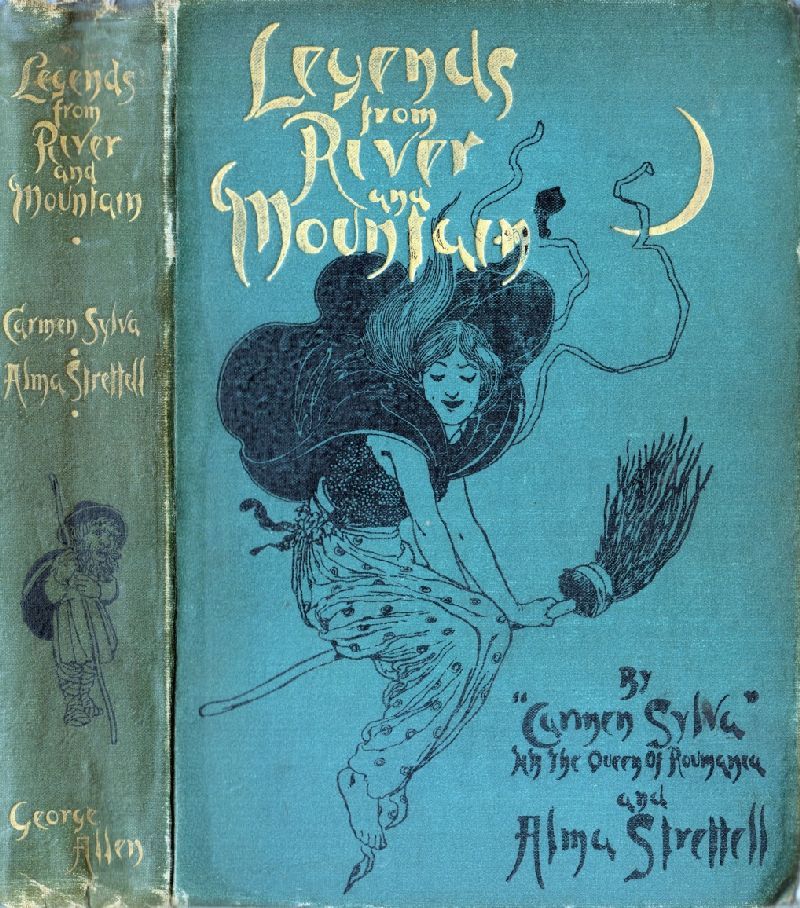

“Legends from River & Mountain” by Carmen Sylva (H.M. the Queen of Romania),

translated into English by Alma Strettel and illustrated by T.H. Robinson

(London, 1896).

“Legends from River & Mountain” by Carmen Sylva (H.M. the Queen of Romania), translated into English by Alma Strettel (London, 1896), containing tales from the volume “Pelesch-Märchen” (Tales of the Pelesh, German edition: 1883) and legends from the volume: “Durch die Jahrhunderte” (Through the Centuries, German edition: 1885).

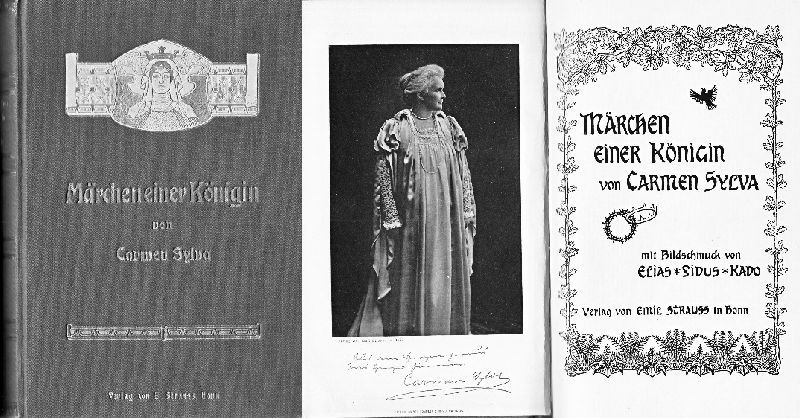

„Märchen einer Königin” (A Queen’s Fairy Tales, German edition, 1901).

Queen Elisabeth in illustrations for the autobiographic tale “Carmen Sylva”

in “Märchen einer Königin” (A Queen’s Fairy Tales, German edition, 1901).

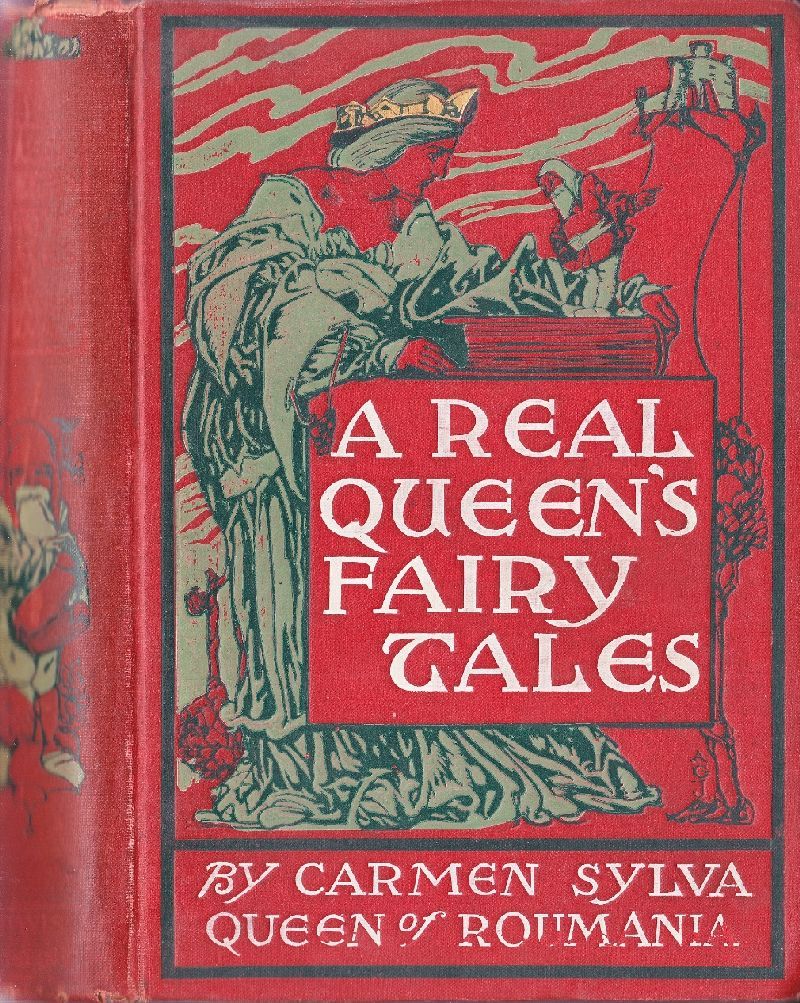

American English edition of the fairy tales by Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva):

“A Real Queen’s Fairy Tales” (Chicago, 1901).

American and British editions of the fairy tales by Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva):

“A Real Queen’s Fairy Tales” (Chigaco, 1901),