Полная версия

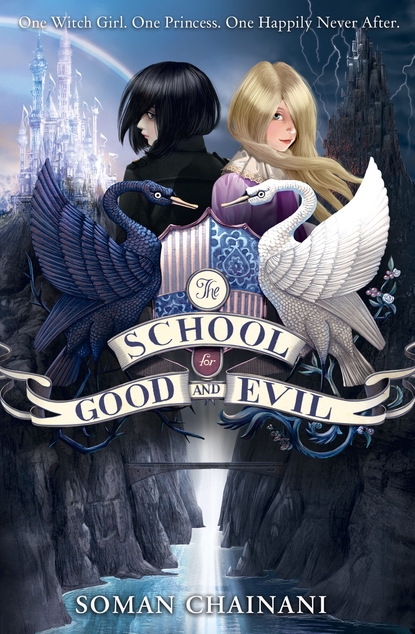

The School for Good and Evil: The Complete 6-book Collection

The Storian plunged to the page: “Stupid girls! They were trapped for eternity!”

“I suspected as much,” said the School Master.

“So there’s no way home?” Agatha asked, eyes welling.

“Not unless it’s your ending,” the School Master said. “And going home together is a rather far-fetched ending for two girls fighting for opposing sides, don’t you think?”

“But we don’t want to fight!” Sophie said.

“We’re on the same side!” said Agatha.

“We’re friends!” Sophie said, clasping Agatha’s hand.

“Friends!” the School Master marveled.

Agatha looked just as surprised, feeling Sophie’s grip.

“Well, that certainly changes things.” The School Master paced like a doddering duck. “You see, a princess and a witch can never be friends in our world. It’s unnatural. It’s unthinkable. It’s impossible. Which means if you are indeed friends . . . Agatha must not be a princess and Sophie must not be a witch.”

“Exactly!” said Sophie. “Because I’m the princess and she’s the wi—” Agatha kicked her.

“And if Agatha is not a princess and Sophie is not a witch, then clearly I’ve got it wrong and you don’t belong in our world at all,” he said, pace slowing. “Maybe what everyone says about me is true after all.”

“That you’re Good?” Sophie said.

“That I’m old,” the School Master sighed out the window.

Agatha couldn’t contain her excitement. “So we can go home now?”

“Well, there is the thorny matter of proving all this.”

“But I’ve tried!” Sophie said. “I’ve tried proving I’m not a villain!”

“And I’ve tried proving I’m not a princess!” said Agatha.

“Ah, but there’s only one way in this world to prove who you are.”

The Storian stopped its busy writing, sensing a pivotal moment. Slowly the School Master turned. For the first time, his blue eyes had a glint of danger.

“What’s the one thing Evil can never have . . . and the one thing Good can never do without?”

The girls looked at each other.

“So we solve your riddle and you . . . send us home?” Agatha asked hopefully.

The School Master turned away. “I trust I won’t see either of you again. Unless you want a rather depressing end to your story.”

Suddenly, the room started disappearing in a sweep of white, as if the scene was being erased before their eyes.

“Wait!” Agatha cried. “What are you doing!”

First the bookshelves vanished, then the walls—

“No! We want to go home now!” Agatha yelled.

Then the ceiling, the table, the floor around them—the two girls lunged to a corner to avoid being erased—

“How do we find you! How do we answe—” Agatha ducked to avoid a streak of white. “You’re cheating!”

Across the room, Sophie saw the Storian furiously writing to keep up with their fairy tale. The pen sensed her gaze, for the words in its steel suddenly seared red and Sophie’s heart burned again with secret understanding. Scared, she clung to Agatha—

“You thief! You bully! You masked-face old creep!” Agatha screamed. “We’re fine without you! Readers are fine without you! Stay in your tower with your masks and pens and stay out of our lives! You hear me! Steal children from other villages and leave us alone!”

The last thing they saw was the School Master turn from the window, smiling in a sea of white.

“What other villages?”

The ground vanished beneath the two girls’ feet and they free-fell into emptiness, the School Master’s last words echoing, blending into the wolves’ call to morning class—

They woke, blinded by sunlight, swimming in puddles of sweat. Agatha looked for Sophie. Sophie looked for Agatha. But all they found were their own beds, in towers far apart.

In Uglification, Sophie tried to ignore all the snickers and focus on Manley’s lecture about the proper use of capes. This took valiant concentration, given Hester’s vengeful glares and the fact that capes could be used for protection, invisibility, disguise, or flight, depending on their fabric and grain, with each type requiring different incantations. Manley blindfolded the students for the class challenge, where students raced to identify their given cape’s fabric and successfully put it to use.

“I didn’t know magic was so complicated,” Hort murmured, massaging his cape to see if it was silk or satin.

“And this is just capes,” Dot said, smelling hers. “Wait until we do spells!”

But if there was one thing Sophie knew, it was clothes. She recognized snakeskin under her fingers, mentally said the incantation, and went invisible under her slinky black cape. The feat earned her another top rank and a look from Hester so lethal Sophie thought she might burst into flames.

Across the moat, Agatha couldn’t turn a corner without seeing Tedros and his mates mimicking hobgoblin lurches, howling gibberish, and beating each other with squashes. Wherever she went, Tedros and company followed, braying and grunting at the top of their lungs, until she finally snatched a squash and jabbed Tedros in the chest with it.

“The only reason this happened is because you chose me! YOU CHOSE ME, you boorish, brainless thug!”

Tedros gaped dumbly as she stormed off.

“You chose the witch?” asked Chaddick.

Tedros turned to find boys staring. “No, I—she tricked—I didn’t—” He pulled his sword. “Who wants to fight?”

With Hansel’s Haven still in ruins, classes were moved to the tower common rooms. Agatha followed a herd of Evers through the Breezeways linking all the Good towers in a zigzag of colorful glass passages high over the lake. While crossing a purple breezeway to Charity, she tuned out gossiping girls and pondered the School Master’s riddle over and over, until she looked up and saw she was all alone. After fumbling through the bubble-filled Laundry, where nymphs scoured dresses, dodging enchanted pots in the Supper Hall making lunch, and trapping herself in a faculty toilet, Agatha finally tracked down the Charity Commons. The pink chaise couches were already full and none of the girls made room for her. Just as she sat on the floor—

“Sit here!”

Kiko, the sweet, short-haired girl, scooted aside. As the others tittered, Agatha squeezed in beside her. “They’ll all hate you now,” she mumbled.

“I don’t understand how they can think themselves Good and be so rude,” Kiko whispered.

“Maybe because I almost burned down the school.”

“They’re just jealous. You can make wishes come true. None of us can do that yet.”

“It was a fluke. If I could make wishes come true, I’d be home with my friend and my cat.” The thought of Reaper made Agatha grasp for another subject. “Um, how’s that boy you wished for?”

“Tristan?” Kiko’s face fell. “He likes Beatrix. Every boy likes Beatrix.”

“But he gave you his rose,” Agatha said, remembering her wish at the lake.

“By accident. I jumped in front of Beatrix to catch it.” Kiko gave Beatrix a dirty look. “Do you think he’ll take me to the Ball? Not every boy can take that she-wolf.”

Agatha smirked. Then frowned. “What ball?”

“The Evers Snow Ball! It’s right before Christmas and every one of us has to find a boy to take us or we’re failed! We get ranked as couples based on our presentation, demeanor, and dancing. Why do you think we all wished for different boys at the lake? Girls are practical like that. Boys just all want the prettiest one.” Kiko grinned. “Who do you have your eye on?”

Before Agatha could vomit, the doors flew open and a busty woman flounced in wearing a bejeweled red turban and scarf that matched her dress, caked caramel makeup, swarthy kohl around her eyes, Gypsy hoop earrings, and jangling tambourine bracelets.

“Umm . . . Professor Anemone?” Kiko gawked.

“I am Scherezade,” Professor Anemone boomed in a ridiculous accent. “Queen of Persia. Sultaness of the Seven Seas. Behold my dusky desert beauty.”

She whipped off her scarf and did a terrible belly dance. “See how I seduce you with my hips!” She veiled her face and blinked like an owl. “See how I tempt you with my eyes!” She shook her bosom and beat her bangles noisily. “See how I become Midnight’s Temptress!”

“More like smoked kebab,” Agatha murmured. Kiko giggled.

Professor Anemone’s smile vanished, as did the accent. “Here I thought I’d teach you to survive 1001 Arabian Nights—dune-ready makeup, hegira fashions, even a proper Dance of the Seven Veils—but perhaps I should start with something less amusing.” She tightened her turban.

“Fairies have alerted me that candy has been vanishing from Hansel’s Haven even while it is under repair. As you know, our school’s classrooms are made of candy as a reminder of all the temptations that you will face beyond our gates.” Her eyes narrowed. “But we know what happens to girls who eat candy. Once they start, they can’t stop. They stray from the path. They fall prey to witches. They gorge themselves on self-pleasure until they die obese, unmarried, and riddled with warts.”

The girls were aghast someone would vandalize the tower, let alone ruin their figure with candy. Agatha tried to look just as scandalized. That’s when the marshmallows fell out of her pocket, followed by a blue lollipop, a hunk of gingerbread, and two bricks of fudge. Twenty gasps came at once.

“I didn’t have time for breakfast!” Agatha insisted. “I didn’t eat all night!”

But no one was sympathetic, including Kiko, who looked sorry that she’d been nice to her at all. Agatha picked guiltily at her swan.

“You’ll be cleaning plates after supper for next two weeks, Agatha,” said her professor. “A useful reminder of the one thing princesses have that villains do not.”

Agatha bolted up. The answer!

“A proper diet,” Professor Anemone huffed.

As the turbaned teacher divulged more Arabian Beauty Secrets, Agatha slumped into the couch. One class and her problems had already multiplied. Between the horror of a mandatory Ball, a week of dish duty, and a decidedly wart-ridden future, she had the crashing realization of just how fast she needed to solve the School Master’s riddle.

“How about poison in her food?” Hester spat.

“She doesn’t eat,” said Anadil, tramping with her through Malice Hall.

“How about poisoned lipstick?”

“They’ll lock us in the Doom Room for weeks!” fretted Dot, lumbering to keep up.

“I don’t care how we do it or how much trouble we get in,” Hester hissed. “I want that snake gone.”

She threw open the door to Room 66 to find Sophie sobbing on her bed.

“Um, snake’s crying,” Anadil said.

“Are you okay, love?” Dot asked, suddenly sorry for the girl she was supposed to kill.

Blubbering, Sophie poured out everything that happened in the School Master’s tower.

“. . . But now there’s a riddle and I don’t know the answer and Tedros thinks I’m a witch because I keep winning challenges and no one understands the reason I keep winning is that I’m good at everything!”

Hester was ready to strangle her right there. Then her face changed.

“This riddle. If you answer it . . . you go home?”

Sophie nodded.

“And we never have to see you again?” said Anadil.

Sophie nodded.

“We’ll solve it,” her roommates pounced.

“You will?” Sophie blinked.

“You know how badly you want to go home?” said Hester.

“We want you to go home more,” said Anadil.

“Well, at least you believe me,” Sophie frowned, wiping tears.

“Guilty until proven innocent,” Hester said. “It’s the Never way.”

“I wouldn’t tell any of this to an Ever, though. They’ll think you’re mad as a hatter,” said Anadil.

“That’s what I thought, but who lies about breaking so many rules?” Dot said, failing to turn her swan crest to chocolate. “Really, this bird is incorrigible.”

“What’s the School Master like?” Hester asked Sophie.

“He’s old. Very, very old.”

“And you actually saw the Storian?” Anadil asked.

“That strange pen? It wrote about us the whole time.”

“It what?” said the three girls at once.

“But you’re in school!” Hester said.

“What can happen in school that’s worthy of a fairy tale?” said Anadil.

“I’m sure it’s just a mistake, like everything else,” Sophie sniffled. “I just need to solve the riddle, tell the School Master, and poof, I’m out of this cursed place. Simple.”

She saw the girls exchange looks. “Isn’t it?”

“There’s two puzzles here,” Anadil said, eyeing Hester. “The School Master’s riddle.”

Hester turned to Sophie. “And why he wants you to solve it.”

If there was one word Agatha dreaded more than “ball,” it was “dancing.”

“Every Good girl must dance at the Ball,” Pollux said, wobbling on mule legs in the Valor Commons.

Agatha tried not to breathe. The room reeked of leather and cologne with its musky brown couches, bear-head carpet, hide-bound books about hunting and riding, and a moose-head plaque flaunting obscenely large antlers. She missed the School for Evil and its graveyard stench.

Pollux led the girls through the dances for the Evers Ball, none of which Agatha could follow, since he kept falling and mumbling it would “make sense once he got his body back.” After tripping a hoof on the rug, impaling himself on the antlers, and landing buttocks first in the fireplace, Pollux barked they “got the point” and wheeled to a group of fairies wielding willow violins. “Play a volta!”

And so they did, lightning quick, with Agatha flung from partner to partner, waist to waist, spinning faster, faster into a wild blur. Her feet caught fire. Every girl in the room was Sophie. The shoes! They were back! “Sophie! I’m coming!” she yelled—

Next thing she knew, she was on the floor.

“There are appropriate times for fainting,” Pollux scowled. “This is not one.”

“I tripped,” Agatha snapped.

“Suppose you faint during the Ball! Chaos! Carnage!”

“I didn’t faint!”

“Forget a ball! It would be a Midnight Massacre!”

Agatha stared him down. “I. Don’t. Faint.”

When the girls reported to the banks of Halfway Bay for Animal Communication, Professor Dovey was waiting. “Princess Uma has taken ill.”

Girls gave Agatha sour looks, since her Wish Fish debacle was surely responsible. With no one to supervise on such short notice, Professor Dovey gave them the session off. “Top-half students may use the Groom Room. Bottom-half students should use the time to reflect upon their mediocrity!”

While Beatrix and her seven minions sashayed to the Groom Room for manicures, the bottom-half girls scurried to peek in on Swordplay, since the boys sparred shirtless. Meanwhile, Agatha hastened to the Gallery of Good, hoping it would inspire an answer to the riddle.

As her eyes drifted across its sculptures, cases, and stuffed creatures lit by pink-flamed torches, she remembered the School Master’s decree that a witch and princess could never be friends. But why? Something had to come between them. Surely this was the mysterious thing a princess could have and a villain could not. She thought about what it could be until her neck prickled red. But still no answer.

She found herself pulled once more to the corner nook, home to the gauzy paintings of Gavaldon’s Readers. Agatha remembered Professor Dovey speaking to that tight-jawed woman. “Professor Sader,” they called the artist. The same Sader who taught History of Heroism? Wasn’t that class next?

This time, Agatha moved through the paintings slowly. As she did, she noticed the landscape evolved from frame to frame: more stores sprang up in the square, the church changed colors from white to red, two windmills rose behind the lake—until the village began to look just like the one she had left. Even more confused now, she drifted along the paintings until one made her stop.

As children read storybooks on the church steps, the sun spotlit a girl in a purple peacoat and yellow hat with sunflowers. Agatha put her nose to the girl. Alice? It had to be. The baker’s daughter had worn the same ridiculous coat and hat every day of her life until she was kidnapped eight years before. Across the painting, an errant ray of sun spotlit a gaunt boy in black beating a cat with a stick. Rune. Agatha remembered him trying to gouge out Reaper’s eye before her mother thrashed him away with a broomstick. Rune too had been taken that year.

Quickly she shifted to the next painting, where scores of children lined up in front of Mr. Deauville’s, but the sun illuminated only two: bald Bane, biting the girl in front of him, and quiet, handsome Garrick. The two boys taken four years before.

Sweating, Agatha slowly turned to the next painting. As children read high on an emerald hill, two sat below, sunlit on a lake bank. A girl in black flicking matches into the water. A girl in pink packing pouches with cucumbers.

Breathless, Agatha dashed back through the row. In every one, light chose two children: one bright and fair, the other strange and grim. Agatha retreated from the nook and climbed on a stuffed cow’s rump so she could see all the paintings at once, paintings that told her three things about this Professor Sader—

He could move between the real and fairy-tale worlds. He knew why children were brought here from Gavaldon.

And he could help them get home.

As fairies chimed the start of the next class, Agatha barged into the Theater of Tales and squeezed beside Kiko, while Tedros and his boys played handball against the phoenix carved into the front of the stone stage.

“Tristan didn’t even say hi,” Kiko griped. “Maybe he thinks I have warts now that I talked to yo—”

“Where’s Sader?” Agatha said.

“Professor Sader,” said a voice.

She looked up and saw a handsome silver-haired teacher give her a cryptic smile as he ascended the stage in his shamrock-green suit. The man who smiled at her in the foyer and on the Bridge.

Professor Crackpot.

Agatha exhaled. Surely he’d help if he liked her so much.

“As you know, I teach fourth session both here and in Evil and unfortunately cannot be in two places at once. Thus I’ll be alternating weeks between schools,” he said, clasping the lectern. “On weeks where I’m not here, you’ll have former students come to recount their adventures in the Endless Woods. They’ll be responsible for your weekly challenges, so please afford them the same respect you’d give me. Finally, given I am responsible for a vast amount of students and a vast amount of history, I do not hold office hours nor will I answer your questions inside or outside of class.”

Agatha coughed. How could she get answers if he didn’t allow questions?

“If you do have questions,” said Sader, hazel eyes unblinking, “you’ll surely find the answers in your text, A Student’s History of the Woods, or in my other authored books, available in the Library of Virtue. Now to roll call. Beatrix?”

“Yes.”

“One more time, Beatrix.”

“Right here,” Beatrix snapped.

“Thank you, Beatrix. Kiko!”

“Present!”

“Again, Kiko.”

“I’m here, Professor Sader!”

“Excellent. Reena!”

“Yes.”

“Again?”

Agatha groaned. At this rate, they’d be here until new moon.

“Tedros!”

“Here.”

“Louder, Tedros.”

“Good grief, is he deaf?” Agatha grouched.

“No, silly,” said Kiko. “He’s blind.”

Agatha snorted. “Don’t be ridi—”

The glassy eyes. The matching names to voices. The way he gripped the lectern.

“But his paintings!” Agatha cried. “He’s seen Gavaldon! He’s seen us!”

That’s when Professor Sader met her eyes and smiled, as if to remind her he’d never seen anything at all.

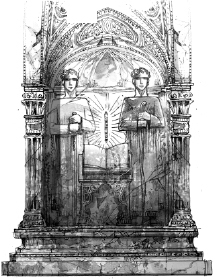

“So let me get this straight,” Sophie said. “There were two School Masters first. And they were brothers.”

“Twins,” said Hester.

“One Good, one Evil,” said Anadil.

Sophie moved along a series of chipped marble murals built into Evil Hall. Covered in emerald algae and blue rust, torch-lit with sea-green flames, the hall looked like a cathedral that had spent most of its life underwater.

She stopped at one, depicting two young men in a castle chamber, keeping watch over the enchanted pen she had seen in the School Master’s tower. One brother wore long black robes, the other white. In the cracked mosaic, she could make out their identical handsome faces, ghostly pale hair, and deep blue eyes. But where the white-robed brother’s face was warm, gentle, the black-robed one’s was icy and hard. Still, something about both of their faces seemed familiar.

“And these brothers ruled both schools and protected the magic pen,” Sophie said.

“The Storian,” Hester corrected.

“And Good won half the time and Evil won half the time?”

“More or less,” said Anadil, feeding a snail to her pocketed rats. “My mother used to say that if Good went on a streak, Evil would find new tricks, forcing Good to improve its defense and beat them back.”

“Nature’s balance,” said Dot, munching on a schoolbook she’d turned to chocolate.

Sophie moved to the next mural, where the Evil brother had gone from ruling peacefully alongside his brother to attacking him with a barrage of spells. “But the Evil one thought he could control the pen—um, Storian—and make Evil invincible. So he gathers an army to destroy his brother and starts war.”

“The Great War,” said Hester. “Where everyone took a side between Good brother and Evil brother.”

“And in the final battle between them, someone won,” said Sophie, eyeing the last mural—a sea of Evers and Nevers bowed before a masked School Master in silver robes, the glowing Storian floating above his hands. “But no one knows who.”

“Quick-study,” Anadil grinned.

“But then surely people must know if he’s the Good brother or Evil brother?” Sophie asked.

“Everyone pretends it’s a mystery,” said Hester, “but since the Great War, Evil hasn’t won a single story.”

“But doesn’t the pen just write what happens in the Woods?” Sophie said, studying the strange symbols in the Storian’s steel. “Don’t we control the stories?”

“And it just happens one day all villains die?” Hester growled. “That pen is forcing our fates. That pen is killing all the villains. That pen is controlled by Good.”

“Storian, love,” Dot chomped. “Not a pen.”

Hester smacked the book out of her mouth.

“But if you’re going to die every time, why bother teaching villains?” said Sophie. “Why have the School for Evil at all?”

“Try asking a teacher that question,” piped Dot, digging in her bag for a bigger book.

“Fine, so you villains can’t win anymore,” Sophie yawned, filing her nails with a marble shard. “What’s this to do with me?”

“The Storian started your fairy tale,” Hester frowned.

“So?”

“And given your current school, the Storian thinks you’re the villain in that fairy tale.”

“And I should care about the opinion of a pen?” Sophie said, whittling nails on her other hand.

“I take back the quick-study bit,” said Anadil.

“If you’re the villain, you die, you imbecile!” Hester barked.

Sophie broke a nail. “But the School Master said I could go home!”