Полная версия

The Forgotten Child

Christmas was always a special occasion to brighten the winter months at Field House. None of us had families to spend Christmas with, so the housemothers did all they could to make it special for us, although they must have had their own families too.

There was no build-up like there is today. The first we knew of it being anything different was on Christmas Eve, when fir trees were brought in from somewhere in the grounds. One was placed in the girls’ dormitory, another in the boys’ and one in the dining room too. The tree in our room was almost up to the high ceiling and wide all around. I remember the lovely scent of the fir needles that pervaded the dormitory. The staff came in and decorated it for us while we watched them, our excitement mounting as they adorned the branches with glittery silver and red tinsel, gold-foil wrapped chocolate coins and, right at the top, a large silver star.

‘Tomorrow is Christmas Day,’ explained my housemother as she put me to bed that evening. ‘If you are all good boys, there will be some presents under the tree when you wake up in the morning and a chocolate coin for each of you. We will come in and give them out.’

This was such an exciting prospect that it was hard to get to sleep that evening, but finally, we all did, and sure enough, when we awoke it was Christmas Day and there were presents all around the bottom of the tree. We leapt out of our beds with squeals of delight, but three of the housemothers were already there too, so nobody had the chance to touch the presents until it was time.

‘You can all sit on the ends of your beds and look at the presents. There are enough for everybody and you can all choose one each, but no squabbling. I am sure you will share them with each other,’ said one of the housemothers.

I could hardly contain my excitement. The presents were all sorts of toys and games and cuddly things – none of them wrapped – so I remember casting my eyes across all this bounty to see if anything particularly appealed. We had been so well brought up to share and take turns that none of us were selfish enough to grab something that someone else wanted. If I chose something that another boy had his eyes on, he might say, ‘I would like that’, and I would give it to him.

‘Here you are,’ I would say. ‘I’ll choose something else.’ And the housemothers would smile at me and make sure I kept my next choice.

I remember the Christmas after my fourth birthday, how excited I was when I spotted something straight away that I would ask for as my choice. It was a round metal thing with coloured circles painted round it, a push-down button at the top and a sort of spike underneath. Having never seen one before, I wanted to know how it worked and what it did. I waited as patiently as I could until it was my turn, hoping desperately that nobody else would choose it first. Fortunately, it was still there, so I went and pointed at it.

‘That’s a spinning top,’ said one of the staff. ‘I’ll show you how it works, if you like.’

‘Yes, please!’ I exclaimed.

She came over and pressed down the button on the top, which sent the top spinning on its spike, so that the coloured circles made patterns. When it went fast they seemed to disappear, but when it slowed down it was wobbling about all over the place, which made me laugh. I loved that spinning top. It was the best toy ever and I played with it a lot, but I let the others have goes with it, too, just as I did with my two toy cars.

One of the other boys would say: ‘Please can I play with your red car?’

‘Yes, you can,’ I would reply.

He would play with it for a while, then he would bring it back and park it under my bed alongside my other car. It was the same if I asked to borrow anyone else’s toy. We were all very good at that, we all shared everything.

What I remember best about our wonderful Christmases at Field House was the food. To start with, the smell of roasting turkey wafted through the house. It was so enticing that I found it very hard to have to wait until lunchtime.

Finally, it was time to go into the dining room, where there was another tall Christmas tree, with tinsel and various other decorations hanging on it, including crackers. We jumped up and down to see the tables specially decorated with red tablecloths and strewn down the middle with more crackers. We were so excited to pull those, but we had to wait till after we’d finished eating. It was a lovely, heart-warming occasion and we had a delicious meal, piled up high. Even I felt full after just one plateful!

Later that afternoon, we all stood together and sang carols round the dining-room Christmas tree, with its lights twinkling. It was a magical time. Most of the housemothers were there, including mine, joining in with us as we sang ‘Away in a Manger’, ‘Once in Royal David’s City’, ‘Jingle Bells’and other well-known festive songs.

We all loved the whole, very special Christmas experience, but it didn’t last long. On Boxing Day the trees came down and everything went back to normal again, except we still had our presents to play with. And I loved my top – I enjoyed setting it off and watching it spin, round and round. I soon discovered that I could make it spin faster and longer if I wanted and after that I spent hours with it, perfecting the way I spun it.

Birthdays were celebrated in a low-key way. The staff would tell us ‘This is Richard’s birthday’ or ‘This is David’s birthday’ and at teatime there would be a cake with a single candle in it, whatever the age. The birthday child would blow out the candle and then we all sang ‘Happy Birthday’ and that was all – no presents. What I hadn’t yet grasped was that with every birthday, the time when I would have to leave drew nearer. None of the children could stay at Field House beyond their fifth birthdays, so I was now perilously close to that time.

CHAPTER 4

Chosen

November 1958 (aged 4) – Physically very fit. Sturdy. Speech fluent. Making much better progress. Is imaginative in play. Likes to play alone. Still has an occasional temper tantrum.

Field House progress report

Every now and then, we older children had to line up along the lawn. Now four and a half years old, I was aware that, after these line-ups, children sometimes left Field House, so I didn’t want to be in the line, but if I tried to hide, one of the staff would be sure to come and find me.

‘Come along, Richard. There are people coming to see you today,’ explained the housemother. ‘And they could become your mother and father. If they decide they would like you to be part of their family, they’ll be able to take you to live with them in their home. Wouldn’t that be lovely?’

I must have shrugged or shown my indifference in some way. I know she wanted me to be excited, and I should have been, shouldn’t I? Some children were, but not me. I didn’t want anything to change, I wanted to stay at Field House for ever.

But the housemother had to get me into the line, so she took a different approach.

‘It won’t take long, then you can go and play again.’

‘Oh, all right,’ I reluctantly agreed.

So, she encouraged me to change, and dressed in my ‘Sunday best’, mainly charity clothes, I joined the line-up on the lawn outside Field House, my eyes staring at the ground and my insides trembling lest someone should pick me.

Couples arrived and joined one of the housemothers to walk along the line, looking at each of us and whispering to each other as they went by. Occasionally, they would stop and talk to a child, then they might ask to take that child for a walk around the grounds. It was all rather unnerving and I was always highly relieved when nobody picked me and I could indeed run off and play.

On one of these line-up days, a couple did stop and talk to me. I think they just asked me my name, how old I was and what I liked doing best. They seemed happy with my answers and turned to the housemother.

‘Can we take him for a walk and get to know him better?’ asked the woman.

So off we went. I told them I liked cars, so they took me to see their big green car, parked in the drive. It looked a funny shape, like a shiny green bell. The man opened the bonnet and showed me the engine, which was quite exciting.

‘Where else shall we go?’ asked the woman. ‘Is there anything you would like to show us?’

My first idea was the Japanese garden, but I thought they might like that too much and take me away.

‘We could go round the lawn,’ I suggested.

The woman took my hand and I led them to my favourite parts of the garden.

‘This is my tree,’ I explained when we reached the tall cedar tree with its low branches. ‘I like to sit in this tree and eat burnt crusts.’

They exchanged glances.

‘Then I took them down the drive.

‘Sometimes we go for walks down to the lane,’ I said. ‘And up to the hills.’

‘That must be fun,’ said the woman.

‘Yes, we sing songs and eat sandwiches and see a man with a monkey.’

‘A monkey?’ asked the man. ‘A real monkey?’

‘Yes, he sits on the man’s shoulder when we walk past.’

There was a pause as we came to the bramble hedge.

‘This is where we pick blackberries,’ I told them. ‘We have little baskets and pick the fruit to put in a crumble.’

‘That sounds nice,’ the woman said. ‘What’s your favourite food?’

‘Steak pie and gravy,’ I said, licking my lips.

They kept on asking me questions, and I tried to be polite, but I wished they would go away and I could get back to playing. Finally, I think they gave up on me.

I was so happy that I ran three times round the lawn before going in for tea.

Although I didn’t want to be picked in these regular line-ups, sometimes, if they didn’t pick me, I would wonder, Why haven’t they chosen me? What’s wrong with me?

I knew that I was getting older and would soon be too old to stay at Field House, but I didn’t want to think about that – I couldn’t quite believe it.

My lovely, kind housemother sat me down one day.

‘Let’s have a talk,’ she said.

‘Have I done something wrong?’

‘No, not at all,’ she reassured me with a smile. ‘But you will soon be five, so it’s nearly time for you to leave Field House and move on,’ she explained. ‘If you don’t have a new mummy and daddy to take you out of the line next week, you will have to move to another house, maybe a house with lots of children, all much bigger and older than you.’

I didn’t like the sound of that.

‘Will you come with me?’ I asked.

‘No, I’m afraid that wouldn’t be allowed,’ she said in her gentle voice.

I thought about that a lot over the coming days and nights, but I couldn’t quite accept it. This was my home, the only home I had ever known. Why couldn’t I stay here? Finally, on the next line-up day, my housemother gave me some nearly-new clothes to put on.

‘Try and keep clean and tidy,’ she said, grinning. ‘No climbing trees today!’

The Matron herself spoke to me after breakfast: ‘Hello, Richard. I’m glad you are looking so smart today. I’m sure you will be glad to know that we have a couple coming to see you this afternoon, so we won’t have to put you in the line for long. They will come and choose you and then I want you to be a good boy and be polite to them and get to know them while you show them round the gardens. Will you be able to do that?’ She waited expectantly with a half-smile. I’d never seen her smiling even the smallest bit before, so I tried to be brave and smile back.

‘Yes, all right,’ I agreed.

So, we all lined up as usual and I was placed near the beginning this time. My housemother came out of the front door with a couple and they walked straight in my direction. This seemed very strange. They ignored all the other children and homed in on me. I suppose it must have been to do with my age and the fact that the staff wanted me to go to a family home, rather than a larger children’s home, so they thought they were doing this for the right reasons. I thought so too, as I was frightened of the idea of all the big boys there might be at the children’s home.

The couple walked over and stopped in front of me, just as Matron had said.

‘This is Richard,’ said the housemother. ‘He’s a happy boy and likes playing in the garden.’ She turned to me and introduced them. ‘This is Mr and Mrs Gallear,’ she told me. ‘Will you take them for a walk and show them round our gardens? They want to know all about you and the things you like.’

‘All right,’ I nodded uncertainly.

The woman was very short and she had a big smile. She seemed really pleased to be there and to see me. But the man wasn’t smiling. He stood back, towering over her.

‘Come on,’ she said in a friendly voice, taking my hand in hers. ‘My name is Pearl and Mr Gallear is called Arnold. Now, where will you take us first?’

As I walked out of the line, I looked back over my shoulder at all my friends, who watched me go away from them, across the lawn with these visitors – still strangers to me.

‘Would you like to see the vegetable garden?’ I asked them. ‘I love watching things grow in the garden.’

‘Yes, that would be lovely,’ Mrs Gallear said in a bright voice. ‘Wouldn’t it, Arnold?’

He grunted, with a slight nod and followed as I led his wife to the path.

‘That’s the boys’ dormitory.’ I pointed through the long window as we passed by. ‘I sleep next to this window.’

‘That’s nice,’ said Mrs Gallear. ‘How many of you are there?’

‘Ten of us,’ I replied. ‘All boys.’

When we reached the vegetable garden, I picked up a small can and watered a row of newly planted seeds. ‘These will be lettuces,’ I said proudly. ‘I helped the gardener sow the seeds.’

‘Well done,’ said Mrs Gallear with a beaming smile. ‘We have a garden at home. Maybe you could come and grow some lettuces in our garden too?’

‘Maybe,’ I agreed, looking sideways at Mr Gallear, unsure whether he wanted me doing anything in his garden.

As we wandered among the rows of vegetables, I looked at each of the visitors in turn. Pearl Gallear was small and slight, with short, dark grey, curly hair, though I don’t think she was very old. She wore glasses, a flowery dress and a long coat over the top. The thing I liked best about her was her smile. Thinking back now, it was a warm, genuine smile – I felt she really liked me.

Arnold Gallear had a serious face. He wore black-framed glasses and looked awfully tall to me, well-built but not much hair. It was only later, when he bent over to pick up a coin and put it in his pocket, that I saw the funny thing he’d done with his hair: he had a big bald spot and he’d combed thin strands of his light brown hair over the bald part. I longed for it to be windy and blow it all away.

‘Do you like vegetables?’ asked Pearl.

‘Yes, we have lovely vegetables every day with our lunch.’

‘Lucky you!’ she said with a tinkling laugh. ‘What other foods do you like?’

‘Steak pie,’ I said. ‘And puddings and gravy … and cakes and burnt bread crusts …’

‘Well,’ she laughed again, ‘I’m glad you enjoy your food!’

Pearl chatted to me all the time and made a very good impression on me. She was quiet, gentle and very kind – I really liked her.

I saw Arnold taking a sideways look at me. He didn’t smile, but he didn’t frown either. I felt unsure of him, because he wasn’t friendly and warm like Pearl. But I was pleased somebody was taking an interest in me – and Pearl certainly was.

‘Where else shall we go?’ she asked.

‘Come and see the Japanese garden,’ I suggested, leading them round to the side of the house and through the gate in the wall.

‘Ooh! Isn’t this beautiful?’ She seemed quite excited.

I took them round to look at the little waterfalls and showed them where the toad sometimes sat, but he wasn’t there that day. I told her what I had learnt about the plants and the animals that lived there.

‘Oh, you are a clever boy!’ said Pearl with an admiring look. ‘Isn’t he, Arnold?’

But Arnold grunted and turned his head away without saying anything. It might have been a ‘yes’ sort of grunt, but maybe not.

Finally, we went a little way down the drive and I told them about our summer outings to the Clent Hills.

‘This seems like a lovely place,’ said Pearl as we walked back towards the house.

‘Yes, I love it here,’ I grinned.

‘We’ve enjoyed talking to you,’ she said, which I thought was rather odd as Arnold hadn’t said a word. ‘But I’m afraid it’s time for us to go now. Perhaps we might be able to come and see you again. Would that be all right?’

‘Yes,’ I agreed readily. Pearl seemed to be a lovely woman – I thought I’d definitely prefer to be with her than with a lot of big boys in a home full of strangers. So, off they went and I ran in, just in time to wash my hands and join my friends for tea.

That night in the dormitory, getting into bed and falling asleep to another bedtime story that I didn’t hear the end of, I didn’t give the visitors another thought. The next day, I remembered they’d been and I wondered whether I would ever see them again. I would have liked to see Pearl, but wasn’t so sure about Arnold. And I didn’t want to hasten leaving my idyllic life with my friends and all the kind staff, so when nobody told me anything, I didn’t ask.

It must have been a few days later, maybe a week, when my housemother sat me down and told me: ‘Tomorrow, your new mother and father are going to come and collect you.’

I was shocked. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Do you remember Mr and Mrs Gallear, the nice couple who came to see you last week?’

‘Yes, but nobody said anything, so I thought they didn’t like me.’

‘Well, they did like you and they want to take you home.’

‘Are they my real mother and father?’ I asked. Children in books always seemed to have mothers and fathers, so I assumed I must have too.

‘Not your birth mother and father, no, but they want to be your foster parents.’

‘I liked her, she was nice.’

‘Good. Well, they will be your foster parents – your foster mother and foster father. You will call them Mummy and Daddy.’

‘Oh.’

‘Won’t that be nice?’

‘Tomorrow?’ I asked, suddenly welling up with tears. ‘Does it have to be tomorrow?’

‘Yes,’ she said gently, giving me a cuddle when she saw how upset I was. ‘Don’t worry, they are looking forward to taking you back with them to their house, which will become your new home. They will look after you. You’re going to have your own bedroom and you will have a lovely time making lots of new friends where they live.’

I couldn’t speak for crying. My stomach went all wobbly and I just couldn’t take all this in. I suppose I didn’t want to and it all seemed so sudden – I had no time at all.

‘Can I take my cars and my spinning top?’

‘Yes, of course you can. We’ll put them in your case to take with you. I expect you will have some more toys to play with at their house, and maybe some new clothes of your own too.’ She gave me another hug.

‘Can’t I stay here a bit longer?’

‘No, little soldier, I’m afraid you can’t, but they’re not coming till after lunch tomorrow, so you can enjoy all this afternoon and tomorrow morning in the garden. Have a good run round, play with your friends and sit in your favourite tree, whatever you like. I’ll come and find you out there when I’ve gathered all your things to pack, then we can talk some more. Would you like that?’

I nodded, as more tears trickled down my cheeks.

‘Here, take my hankie.’

It was a fine summer’s day and I walked around all my favourite places, ending up on a branch of the cedar tree. How could this happen to me? I knew others had gone to foster homes before me, but I couldn’t talk to any of them to find out if they were happy there.

At bedtime I was tearful and my housemother soothed my fears as best she could.

‘What if I don’t like it there?’ I asked her.

‘You will like it,’ she reassured me. ‘It may take you a little time to settle and get used to belonging to a proper family, getting to know them better, and all their routines. You’ll soon forget all about us. You will make new friends and I expect you’ll be starting school soon. You’ll love school, you can learn all sorts of new things at school.’

She did her best to inspire me with confidence, but it didn’t really work. For once, I didn’t fall asleep before the bedtime story finished – I don’t think I was even listening. As I lay in my bed with the lights out, a shaft of waning daylight shining across my bed from a crack in the curtains, I hoped against hope that when I woke up in the morning it would all be a dream and I wouldn’t have to leave after all.

1959–71: THE CRUEL YEARS

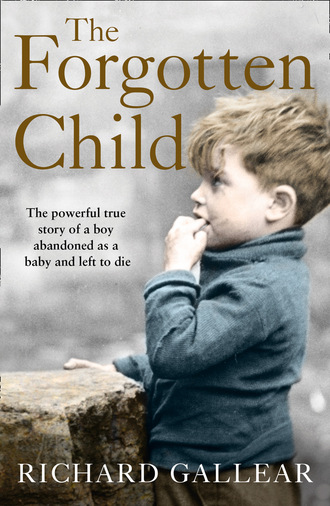

Richard at school, aged 8

CHAPTER 5

Goodbye to Happiness

July 1959 (4 years, 8 months) – Fine healthy boy. Much more stable and happier. Full of imagination, conversation, knowledge of everyday things.

Richard’s last progress report before leaving Field House

30 August 1959 was a beautiful sunny day, but it didn’t feel sunny to me. It was the day my cosy world fell apart. That afternoon I would have to leave the only home I’d ever known – a happy home of fun and laughter with my friends, a secure place where every adult loved us and cared for us. I knew nothing of my beginnings, but I did know I didn’t want to leave Field House. I didn’t want to go and live anywhere else, I wanted to stay there for ever.

It was my last morning so I went to all my favourite places. First, to the vegetable garden, where I had ‘helped’ so often. Everything was growing well, including ‘my’ lettuces, poking up through the soil, and the runner beans I’d planted and watched growing up their canes.

‘I’m leaving today,’ I told the kindly gardener, trying to put on a brave face.

‘Are you now?’ he said. ‘We’ll miss you.’ He paused. ‘Have you got time to pick a few of these beans for the kitchen before you go? Then you can eat them for lunch.’

‘Yes, please,’ I said, perking up at the thought.

Next, I visited the Japanese garden and said goodbye to my friend the toad, who sat and croaked as if he understood.

The rest of the morning went far too quickly and when I went in for lunch, I was overjoyed that it was steak pie, mash and gravy with ‘my’ beans. It was all delicious, so I had another helping.

The housemother at our table told the other boys that I was leaving and they all came up to say goodbye to me as we left the dining room. I didn’t like them saying goodbye – I didn’t want to say goodbye, I didn’t want to go.

Finally, I went to my dormitory, where my housemother was packing my few belongings into a little, scuffed leather suitcase and ticking them off on a list.

‘I’ve packed some spare clothes for you,’ she explained in her kindest voice. I didn’t realise it at the time, but perhaps she didn’t want me to go either. ‘I’ve put in your favourite toys too.’

‘My cars?’ I asked.

‘Yes, both your cars and your spinning top.’

I pulled open the drawer by my bed: it was empty.

‘Where are my conkers?’ I asked, my anxiety rising.

‘In your case.’

I tried desperately to think what else I might need. Then I realised …