Полная версия

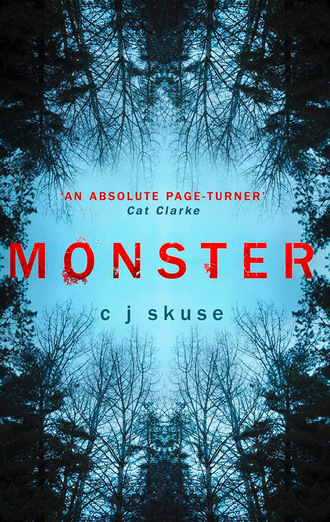

Monster

The more I tried to clear my mind, the more it would fog till it felt like Head Girl was a rope dangling off a cliff face and I was barely clinging on. But cling on I did. I bottled and I clung. Everything I wanted to say, I kept to myself. Everything I wanted to answer her back about—the comments about my ‘scrawny wrists’ as I wrote in the diary, my ‘distinctly miserable face of late’ that might put off prospective parents at the Christmas Fayre—I held back. I swallowed it all down with a glass of tepid tap water and left it at that.

By Monday morning, Seb had been missing for exactly five days and I was losing it rapidly. I felt like a fish on the end of an unending reel.

French:

‘Natasha, est ce qu’il ya une piscine près d’ici?’

Something about swimming pools. ‘Er, non.’

‘Non?’

‘Non, Madame.’

‘Ah oui. Maintenant, nous sommes aimerons aller au la plage.’

Plage was beach. I think. Or plague. ‘Oui, la plage.’

‘Pouvez-vous me donner des directives à la plage, s’il vous plaît?’

Something about medicines to take when you had the plague? Or was she asking for cafés near the beach? My mind was a blank page. I had nothing. ‘Uh, non?’

‘Non?’

‘Oui. Er, non.’

Le grand sigh.

Maths:

‘With that in mind, Natasha, what is the value of n?’

‘The value of n?’

‘Yes, on the board. See where it says n? What is the value of n, if we know that x = 40 and y is 203?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know?’

‘No. What was y again?’

English Lit :

‘So, studying these passages in Jane Eyre and A Tale of Two Cities, how do we begin to compare and contrast some of the ways in which Victorian novelists use landscape to lend resonance to their work? Natasha?’

‘What?’

‘Didn’t you hear what I just said?’

‘Uh, no, sorry, miss.’

Big sigh. ‘The landscape in these two books. How does it lend resonance?’

‘I have no idea.’ Sniggers from the back.

It’s not like you, Natasha. It’s not like you. It’s not like you, not like you, not like you.

The only light that shone onto that day was when I saw the little white Bathory Basics van coming up the drive just before sunset. It pulled up on the gravel driveway just to the left of the front entrance, near the side door to the kitchens. I passed Mrs Saul-Hudson in the front porch.

‘It’s all right, ma’am. It’s just Bathory Basics with the turkeys for Christmas lunch.’

‘Oh wonderful, Natasha. I’ll leave you to deal with it. I’ve got the police on their way. Do you know where Dianna is?’

I stopped in my tracks. ‘The police? Is everything all right, ma’am?’

‘Yes yes yes,’ she said, all flustered and hair-flicky, looking all about her for something. ‘They come every year around this time. Just checking on who is staying over Christmas. Making sure we’ve done our safety checks, that’s all. All quite routine. Have you seen my handbag? Oh, I must have left it upstairs.’

‘Do you need me to talk to the police with you, ma’am?’

‘No, I need Dianna. You’ve got enough to deal with.’

‘Is it about the man in the village who was killed, ma’am?’

‘Yes,’ she said and minced off upstairs without another word.

Bloody Dianna, I thought. Bloody bloody bloody Dianna. Why was she the one to help her talk to the police about it? What about me?

I tried to shake the image of the blonde assassin from my mind as I stepped out onto the front mosaic to greet Charlie Gossard from the shop and try to be happy. I’d had a substantial crush on Charlie for a while now. His dad ran Bathory Basics and he worked there, serving customers and ‘out the back’ though I never really knew what went on ‘out the back’. It had started with the odd flirty comment about what I was buying whenever I walked there on a Saturday morning for provisions, then it progressed to long looks across the freezer in the summer. Now, we were into conversations and every now and again he’d give me some sell-by pies or sweets if there were any due for chucking out. I hadn’t told him about Seb being missing or anything serious like that—our conversations mostly ran to school or what Xbox game he’d recently bought and what his top score was.

He caught sight of me as he got out the driver’s door. ‘Hi, Nash.’

‘Hi, Charlie,’ I said.

‘How are you?’

‘Yeah, fine thanks.’

He was big into gaming, and even though I wasn’t at all, I enjoyed listening to him talk. He could have been reciting the phone book and I’d listen to him. Charlie had short blond hair, blue eyes and always wore tight t-shirts, even in winter, which you could see his nipples through. Maggie said he was a ‘un renard chaud’, which meant a hot fox, but I just thought he was lovely. There was always a long white apron tied around his waist, usually smeared with grubby fingermarks.

‘Do you need any help?’

‘Yeah, if you don’t mind. Thanks.’

His smile cut a diamond into the early evening light and he went to the back doors of the refrigerated van to unlock them, then reached in to get one of three humungous turkeys out for me to carry.

‘She’s a heavy one, mind. You got it?’

‘Yeah,’ I said, straining to hold it in both hands and making my way towards the kitchen door. He grasped the other two, one in each hand.

‘Dad said make sure your cook knows they’re premium birds. KellyBronze. Free range, the lot.’

‘Oh, great,’ I said, struggling a little with the weight of mine as he edged past me and opened the side door to allow me inside. Cook was delighted and, as she and Charlie settled the invoice, I hung around, even though I knew I had no business being there. I was just waiting. For anything. For some little shred of Charlie that I could think about for the rest of the day. Something to send me to sleep smiling tonight instead of crying.

When the invoice was settled and he and Cook had talked about cooking times and types of stuffing and ‘succulence’, he walked back out with me to the annoyingly nearby van.

‘So,’ he said. ‘I guess you go home for the holidays tomorrow then?’

‘Yeah. I guess so.’

‘Not looking forward to it?’

I shrugged. ‘It’ll be nice to see my parents. Yeah. Yeah, it’ll be nice. Presents and Midnight Mass and everything.’

‘Oh, we went one year. Pretty boring really.’

‘It’s tradition though, isn’t it? My mum and dad enjoy it.’

‘Yeah, it is. Gotta keep the old folks happy.’

‘Yeah.’

We both laughed, a nervous sort of laugh that went on as long as it could because it was obvious neither of us knew what to say next. We’d run out of conversation so quickly, I hadn’t seen it coming. I had nothing in reserve to impress him with. I did a bit of subtle eye-batting and leaning in the hope of … What was I hoping for? For him to take me in his arms and ravish me right there in the school driveway? I didn’t know. I just knew I needed something from him. Something more.

‘What are you getting for Christmas then?’ I asked, hopelessly. Desperately.

He laughed. ‘Probably some Boxing Day overtime and a thick ear.’ He smiled, wringing his hands like they were cold. I did the same, mirroring his movements.

‘Are yours freezing too?’ he asked, reaching for them and taking them in his. They were warmer than mine, but at that moment I didn’t care if he’d been lying about having cold hands just so he could hold mine. I didn’t want him to let go. ‘Yeah, they are.’ That tiny moment, with him holding my hands in his, made the day seem finally worth getting up for.

‘I’m all right now,’ I said, regrettably pulling them away and looking down to hide the flames in my cheeks.

‘Listen, you better get in and warm up before they fall off. I’ve got another twelve of these to deliver before the end of the day. Have a great Christmas, all right? And I’ll see you next term.’

‘Yeah,’ I said, as I watched him make his way back to the van. ‘Charlie?’ I called, when he was almost in.

‘Yeah?’ He looked back.

‘You have a great Christmas too.’ And we both smiled at each other. For now, that would have to be enough.

Monday night after Prep and monitoring the Pups’ bedtime, I bathed and wrapped myself in my school-approved navy dressing gown and raspberry slippers with the school crest on and went down to Mrs Saul-Hudson’s office for our usual routine of cocoa and diary. She was sitting at her desk when I knocked and went in, closing the door behind me.

‘Oh, Natasha, is it that time already?’ she said, already in her pyjamas and dressing gown herself and looking more flustered than normal. ‘Sorry, I’ve got such a lot to do before tomorrow.’

‘Good evening, ma’am.’ I placed her cocoa mug down in front of her, my tap water down in front of me, and opened the diary to tomorrow’s page so she could see it. ‘It’s all done for you to check.’

‘Wonderful. Before we go through tomorrow’s notes, have a seat. I wanted to talk to you about something.’

‘Yes, ma’am?’

She took a sip of her cocoa and I took a sip of my water. Then she settled down the mug. ‘Lovely. Just right as usual. Right, last day of term tomorrow, we’ve got lots of visitors coming. Who is supervising Pups all day?’

I opened my notebook and clicked on my pen. ‘The usual staff, ma’am, plus I’ve allocated three prefects from Tudor, Hanover and Windsor House to the three groups as well. No lessons means lots of extra hands on deck, which is great.’

‘Excellent. And how about the Tenderfoots?’

I checked my notes. ‘Two prefects, three members of staff and two TAs. That should be quite enough, ma’am. A lot of the Tenderfoots have gone home early.’

‘Good, and the Christmas Fayre?’

‘Stallholders will be arriving from ten a.m. and the Years Nine and Ten have been briefed by their form tutors about helping set up stalls and—’

‘What about the play?’

‘Years Nine and Ten will be setting out the chairs once they’ve helped with the stalls.’

Mrs Saul-Hudson smiled and sat back in her large leather chair, like a queen testing out a new throne. ‘Where would I be without you, Natasha?’

I smiled and blushed at the same time, taking a large sip of my water.

‘So how are you bearing up? It must be very hard on you and your parents with Sebastian still not found.’

She’d sucker-punched me, bringing Seb into the conversation so quickly, but in a way I was glad she’d found time to care.

‘I’m trying not to think about it really, ma’am,’ I said. ‘Not much I can do by worrying.’

‘That’s the stuff,’ she said proudly. ‘Keep busy, that’s always the best way. No sense in worrying. Worrying, I always say, does not empty tomorrow of its troubles, just empties today of its strength. You bear that in mind, won’t you?’

‘I will, ma’am,’ I said, once I’d figured it out.

‘And you’re doing a marvellous job here so it would be a shame if … well, if things started to slip.’

I didn’t know what she meant by that at that exact moment, but I didn’t have time to figure it out because the next demand came swiftly round the next corner.

‘Oh, and in the morning I want you to arrange some signage to go up once the choral procession through the woods is over. I’ve asked Mr Munday to … well, we’ve taken steps anyway, just in case anything grisly is about. I’m sure there isn’t but, well, best to be safe.’

‘Yes, ma’am. Just regulation “Keep Out” signs, was it?’

‘Yes. Nobody will be going up there over Christmas anyway, but we need signs keeping anyone out of the woods and away from the ponds in case they freeze over.’

I made a note in my book. ‘Yes, ma’am. Is this what the police suggested we do?’

‘Hmm?’ she said, looking up from her papers in alarm as if I’d just asked her what method she suggested I hang myself with.

‘Your meeting with the police this afternoon? They were here to talk about the man in the village and the … beast?’

‘Oh that!’ she said, almost shrieking with laughter. ‘Oh that, yes. Yes, the police did say we needed to take extra precautions.’

‘And … Dianna was a good help with the police?’

‘Yes, wonderful. Actually, you really have both been a constant support this year. And without any detriment to your grades. I don’t know how you and Dianna do it, I really don’t.’

I poured a mental pail of cold water over the flames that had just ignited in my mind. Dianna? A constant support? A constant thorn in my side, rather. A constant interloper on my duties, definitely. ‘Well, I can’t speak for Dianna but I enjoy it, ma’am. I like helping out.’

‘Well, you’ve both been a marvel. How is the play coming along?’

‘Oh we’re almost there, ma’am. If you’d like to come and watch the dress rehearsal, we’ll be starting just after Prayers tomorrow morning.’

‘Lovely, yes, I might do that. And talking of Prayers …’

Here it comes, I thought. This is it. This was the moment I’ve been waiting for. My heart began to pump like a clubhouse classic.

‘Would you be an absolute dear and set out the hymn books first thing tomorrow, please? I meant to ask Clarice Hoon but I never got round to it. Oh and breakfast tomorrow—’

‘I can monitor it,’ I said quickly, so as to squeeze the information, the golden information out of her just that bit quicker. ‘Sorry, ma’am, was there something else you wanted to say about Prayers?’

‘Uh, yes, erm, I’ve forgotten what it was now,’ she chuckled. ‘I’m sure it’ll come to me. I must just tidy up these last few things and show my face at the staff Christmas party. I promised I’d do a little speech and announce Employee of the Year. Any idea where that gold picture frame I got from the mother-in-law last Christmas is?’

‘Yes, it’s on your tallboy in your apartments, ma’am.’

‘Oh good, I’ll wrap that up quickly and give that as a prize. Was there anything else?’

‘Er, no, ma’am.’

She got up from her desk chair as I got up from mine, and went over to her corner armoire and took down a coat hanger from which hung her Christmas end-of-term red trouser suit. ‘Be a dear and go up and hang this in my bedroom would you?’

I looked at her. I waited for her to look at me. Any sign, any inkling, any vestige of good news, vanished from her face.

‘That’ll be all for tonight, thank you, Natasha,’ she said finally, with a knotted brow, clicking off her desk lamp and leaving me in darkness.

3 Insidious

I spent a fitful night, worrying about Seb and angsting over Head Girl. Obsessing over why my dad hadn’t called me with news. Fixating over why Mrs Saul-Hudson hadn’t mentioned some shred of hope that that badge was mine in our meeting. If I got that badge I would be able to cope better with Seb’s disappearance, I knew I would. I’d be able to focus myself on my duties and I would stop worrying so much. If I didn’t get it, what then? What the hell would I do? Who the hell was I at this school if I wasn’t Head Girl? Just some wannabe?

That Tuesday morning, the last day of term, I had a phone call.

I was waiting to be connected to my dad on the public phone outside the school office. There was a shiny prospectus on the shelf and I was absentmindedly peeling through it while I waited. It stated that Bathory School ‘prides itself on its record of pastoral care’. I looked through the pages of all the girls, six-year-old Pups, wide-eyed Tenderfoots, spotty Pre-Pubes, proud prefects and perfect Head Girls of years gone by, action shots of athletics and gymnastics, wondrous gazes down microscopes, contented smiles while reading books on beanbags, playing cellos in the Music room, waving through coach windows on the way to Switzerland, Venice or Amsterdam. I’d done all of that. I’d had all these experiences. My parents were paying £9,000 a term for all this and it wasn’t as though they were rich, not like a lot of the other girls. My mum and dad ran a bakery, that was all. They weren’t loaded by any stretch of the imagination. But they’d sent Seb to a private school, so they sent me too. I knew it was a struggle. I knew I had to do my best.

‘Nash, hi, it’s your dad.’

I closed the prospectus. ‘Hi, Dad.’

‘Nashy, it’s good to hear your voice, darling.’

I wanted to cry. I’d forgotten how much I’d missed his voice. ‘Is everything okay? You don’t usually phone this earl—’

‘I know, darling.’ He’d called me ‘darling’ twice. This really wasn’t good.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘Uh, it’s Seb.’

That was all he’d needed to say. The bottom dropped out of my world. I reached behind me and felt for the corridor wall so I could lean against it.

‘Nash? Nash, darling, are you there?’

‘Yeah.’ I didn’t dare say anything. I didn’t want the silence on the line to be filled with words I’d always dreaded I’d hear. Words from my nightmares. But I had to ask. ‘What’s happened?’

‘Well, there’s still nothing. They think he’s gone off the map a bit.’

I sank back in the big leather swivel chair and it turned me towards the wide bay window. He hadn’t said dead. He still wasn’t past tense. There was still hope.

‘Oh,’ I said.

I could hear Dad scratching his stubbly chin, another bad sign. He hadn’t shaved. By the way he was talking so quietly and slowly, it sounded like he hadn’t slept either. He always talked like that when he’d done a night shift. ‘They’ve made contact with three of the lads on his expedition. Apparently, three of them went off to spot a pod of manatee while the others returned to camp. Seb’s group didn’t come back. I’m sure all will be well. You know Bash. If he fell into a pit of snakes he’d come up wearing snakeskin boots.’

This was Dad trying to make me feel better. It didn’t help. All it did was make me think my big brother had fallen into a pit of snakes.

‘He’s more than likely just gone somewhere remote where there aren’t any phones and he can’t get in touch.

‘We’re catching a flight out there this lunchtime. Managed to get a couple of cancellations. So, I’m afraid, you’ll have to stay there, baby, at least for now.’

‘What?’ I said. ‘Can’t I come?’

‘We can’t come and get you, darling, we’ll have to leave for the airport in a couple of hours.’

‘But I could get a train or something.’

‘It’ll take too long. We’ve got to get our flight. Look, you stay there, where you’re safe. Where we know where you are. We spoke to your Headmistress and she said Matron’s going to be staying over Christmas as well so you won’t be on your own.’

‘So, the Saul-Hudsons aren’t staying?’ I said. ‘First I’ve heard.’ They never went away for Christmas, always New Year skiing, but never Christmas. They always stayed here in case any girls were going home later.

‘Yeah, she said they’re leaving tonight to go skiing or something in Scotland. There’s a few other girls staying as well as you she said. Okay? Nash? They said Matron’s very happy to stay instead of them.’

‘Okay, Dad,’ I said. Cowards, was all I could think. And then my mind went to all the Christmas presents I’d wrapped and put under the loose floorboard in my room. I couldn’t wait to give Dad his. It was this board game he used to play as a kid and thought they’d stopped making. I got it on eBay months ago when I was home for the summer. When Seb was there. We’d had a barbecue for his birthday. We were always together for birthdays and Christmases. Always. Always.

‘What about Christmas?’ A single tear fell into the phone mouthpiece. I rubbed my cheek.

‘We’ll have our Christmas when we get back. All four of us. Okay? Try not to worry too much, Nashy. They’ll find him by then, I know they will.’

I swallowed down a lump of emotion and built a dam for any more tears. There was nothing to cry about yet, I kept telling myself. When I got off the phone, the pain in my throat was worse, but I wouldn’t cry.

‘There’s nothing to cry about, stop it. Stop it,’ I said aloud.

Often, at times where I didn’t know what to do, I’d hear Seb’s voice in my head. He was always full of advice. He always said the right thing.

Suck it up, Nash. I’m fine. Just fancied being on my own for a bit, that’s all. Typical Mum and Dad to panic and get the Embassy involved. I can look after myself.

I could hear it. But I didn’t believe it.

I was in the Chapel, already dressed in my Bob Cratchit outfit for the dress rehearsal straight after morning Prayers. Even though I’d spent a fairly sleepless night, I’d been tasked with setting out the hymn books and assembling the right hymn numbers on the board above the lectern so I focused on the task at hand. I was a mere minutes from the official announcement of Head Girl and I had to put everything else out of my mind.

The Chapel was set apart from the main school, at the start of the wooded valley known as the Landscape Gardens. It was the first building you saw at the bottom of the path. Warm, wooden, bedecked in burgundy and navy curtains, carpets and prayer cushions, it was where we worshipped, where we heard any big announcements and where girls ran if they needed help from a higher source.

‘Hi, Nash.’

Clarice Hoon and a couple of her hangers-on, Allie Powell and Lauren Entwistle, sauntered in and took early places right on the back bench. I heard the creaking of their pews, whispering and a few giggles.

I carried on putting up the numbers on the hymn board. Two five six. One one nine. Twenty-three. Don’t get angry unless you have to, came his voice in my mind. They’re not worth your anger or your tears. ‘Any news about your brother yet?’ Clarice called out. I looked over to them. They had their feet up on the pew in front. ‘Bet you’re worried about him, aren’t you?’

I went over to the organ and got the music sheets ready for Mr Rose.

‘He’s really hot,’ said Lauren.

‘I saw him at Sports Day last year. He came with your parents, didn’t he?’ Allie this time—like Clarice was working them both like a ventriloquist’s act. More giggles. More whispers. ‘Has he got a girlfriend?’

There was a cloth underneath the eagle lectern. I bunched it up and wiped over the top and around the eagle’s bald head, trying hard to zone them out. They’re idiots. They couldn’t find their own backsides with both hands. Don’t even listen. Block it out.

‘Why are you ignoring us, Nash?’

She’d been like this ever since Fourth Form. Last summer I’d reported her for pushing a Pup down the main staircase. There were many things I hadn’t reported her for as well.

‘Just trying to get this place ready,’ I muttered, keeping my head down as I finished polishing the lectern. Now I had done everything I had to do. The hymn books were laid out. The lectern and music were ready. I had to go back down the aisle, past them, to get out of the Chapel and rejoin my class.

I knew one of them would move the moment I was level with them. She blocked my way with her whole body. Don’t vent it. Keep it in check. Stay strong.

‘Let me past, please, Clarice.’

Her face was thick with foundation and blusher. Her breath smelled of sour milk. ‘Why won’t you talk to us? Are you too good for us or something?’

Acid began filling my chest. ‘I have nothing to say to you.’ Lava bubbled up in the middle of my chest. Think of Head Girl. Set the example.

‘Nothing to say? Not like you, is it? You had plenty to say to Saul-Hudson when you reported me.’ She whipped her hair flirtatiously over one shoulder. ‘You never report Maggie and she’s done a lot worse than I have.’

Avoid eye contact. ‘You had your revenge,’ I said, remembering the start of term. She’d put tacks in my outdoor shoes. She never admitted it, but I knew it was her.