Полная версия

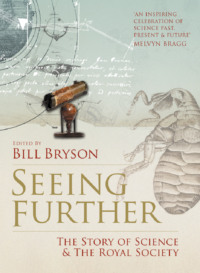

Seeing Further: The Story of Science and the Royal Society

The most surprising, and wonderful composition was that of Whiteness. There is no one sort of Rays which alone can exhibit this. ’Tis ever compounded, and to its composition are requisite all the aforesaid primary Colours, mixed in due proportion. I have often with Admiration beheld, that all the Colours of the Prisme being made to converge, and thereby to be again mixed,…reproduced light, intirely and perfectly white.

This was more interesting, if scarcely more believable, than the Odd Monstrous Calf. It was ordered that the author be solemnly thanked; also that Boyle, Hooke and the Bishop of Salisbury peruse and consider it and report back.

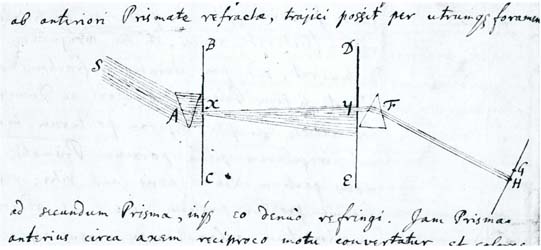

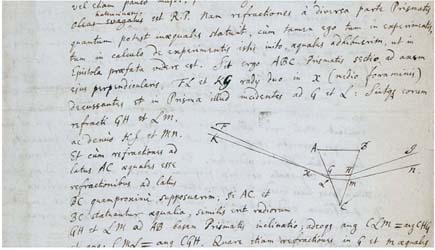

What followed is a story told many times. Newton’s experiment of sunlight refracted by two prisms – so ingeniously conceived, carefully performed, and exquisitely narrated – came to be seen as a landmark in the history of science. It established a great truth of nature. It created a template for the art of reasoning from observation to theory. It shines as a beacon from the past so brightly as to cast the rest of the Society’s contemporaneous activity into relative shadow.

But this is by definition hindsight. That week in February, thinking nothing of history, Hooke dashed off a critique in a matter of hours. He claimed that he, as Curator of Experiments, had already performed such experiments many hundreds of times. He assured the Society that light is a pulse in the ether and that a prism adds colour to whiteness. He infuriated Newton by wielding the word ‘hypothesis’ as a stiletto. Oldenburg published Newton’s entire letter in the Philosophical Transactions, and words of admiration began to come from all across Europe, but Newton was peevish and thin-skinned. He had thought the Royal Society would finally be the audience worthy of him: ‘For beleive me Sir,’ he had told Oldenburg, ‘I doe not onely esteem it a duty to concurre with them in the promotion of reall knowledg, but a great privelege that instead of exposing discourses to a prejudic’t & censorious multitude (by which means many truths have been bafled and lost) I may with freedom apply my self to so judicious & impartiall an Assembly.’ Newton’s dispute with Hooke grew into a lifelong enmity. His distaste for wrangling drove him away from the Society for years to come – years spent largely in the secretive study of alchemy and scripture. He did not publish about optics again until he was an old man and Hooke was dead and buried.

It all seemed so innocent at the time. The meeting of 15 February began with a reading of the minutes from the week before. Cornelio’s claim about tarantulas needed further discussion: ‘some of the members remarking, that it would be hard to accuse of fraud or error Ferdinand Imperato and other good

Diagrams from letters from Isaac Newton to Henry Oldenburg discussing the doctrine of light and colour, 6 June 1672 (above), and a prism diagram, 13 April 1672 (below).

authors, who had delivered from their own experience, so many mischievous effects of the bite of tarantula’s’. They asked Oldenburg to find out what Cornelio had to say in response to those famous men. Then Hooke said that his own observations contradicted Wallis’ idea about the closeness of the Moon causing a rise in the mercury of the barometer. Then Hooke presented his comments on Newton. ‘Nay,’ he said, ‘and even those very experiments, which he alledgeth, do seem to me to prove, that white is nothing but a pulse or motion, propagated through an homogeneous, uniform, and transparent medium: and that colour is nothing but the disturbance of that light…’

‘The same phaenomenon,’ Hooke added, ‘will be solved by my hypothesis, as well as by his, without any manner of difficulty or straining.’ The next week he brought in a candle, to show that, besides the flame and smoke, a continuous stream rose up from it, distinct from the air. Soon after, he showed another phenomenon in a bubble of soapy water, ‘which had neither reflection nor refraction and yet was diaphanous’. He observed it carefully: colours swirling and changing; bubbles blown about by the air. ‘It is pretty hard to imagine,’ Hooke told them, ‘what curious net or invisible body it is, that should keep the form of the bubble, or what kind of magnetism it is, that should keep the film of water from falling down.’ Really, it was hard to know anything at all.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.