Полная версия

An Irish Nature Year

4th Song thrushes, robins, blackbirds and sparrows are in full voice. Blue tits are singing too, mostly variations of a chirrupy ‘chee-chee-purrrr-ah’. In woodlands, the dominant proclaimer this month is the great tit. Its most common declaration is a ringing, far-reaching, high-low refrain: ‘Teach-er! teach-er! teach-er!’ It also sounds like a vastly amplified squeaky wheelbarrow. This basic phrase is often reworked and embroidered with grace notes. Seventy different utterances, including alarm calls and songs, have been identified among great tits, with each bird normally having a repertoire of about eight songs. When a male is defending his territory, he uses different songs in different areas to fool potential intruders into thinking they are facing multiple birds instead of a lone, resourceful individual. The great tit is the largest of its family to visit gardens. Weighing eighteen grams, it is considerably bulkier than the coal tit or blue tit. It has a black head with white cheeks, a yellow breast and an olive-green back. It also sports a vertical black chest stripe. Males with the widest stripes are most attractive to females.

5th Wheels of jagged dandelion leaves have been expanding since the start of the year, pressed flat against the ground. In milder areas their spring flush of flower is beginning. Within a month their cheery yellow heads will cover grassy verges and weedkiller-less lawns. Some will host pollen beetles, tiny, shiny, black or greeny-bronze insects that tumble about among the petals. Each flower is a composite of individual florets (sometimes over two hundred) with each having a reservoir of nectar and a dusting of pollen. This makes them an important source of food for early bumblebees, honeybees, solitary bees, hoverflies, butterflies and other insects. About a dozen moth species lay their eggs on the plants, which then feed the caterpillars. Later, when the clocks form, goldfinches and house sparrows pluck the seeds. There is no definitive dandelion species. Instead, there is an aggregate of hundreds of microspecies: over seventy different forms have been identified in Dublin alone. Look carefully at a few dandelions in the coming weeks, and you will see how they differ in leaf shape and coloration. Many other factors vary, but these are the easiest to spot.

6th Seabirds are putting on their breeding plumage, which makes them easier to identify. A small but striking bird is the black guillemot, which is a deep sooty brown (nearly black), with a well-defined white wing patch. The legs and inside of the mouth are a rich coral red. It is an auk, a family that includes guillemot, puffin and razorbill. Black guillemots are found all along the coast and are easily spotted in the relatively calm water of various harbours, including Bangor, Dingle, Dún Laoghaire and Howth. The birds float quietly, most often in ones and twos, and disappear from view periodically, as they dive for small crustaceans and fish. Occasionally a small group flies low and fast over the waves. The species’ diminutive size and habit of nesting in crevices and holes in walls led to its common names in Ireland of sea pigeon and rock dove (not to be confused with the European rock dove, mentioned on 16 January). In Roundstone in County Galway, a vernacular name was ‘parrot’, according to the Reverend Charles Swainson’s 1885 book, The Provincial Names and Folklore of British Birds. Britain and Ireland are the black guillemot’s southernmost breeding range. It breeds as far north as Greenland and Alaska.

7th Butterbur is in flower in milder areas. Petasites hybridus is like a better-looking, jumbo version of its invasive relative, winter heliotrope (P. fragrans). Growing along rivers, damp roadsides and other moist places, it carries batons of pink-tipped, tasselled, tubular flowers, thirty to forty centimetres tall. The round and scalloped leaves, emerging now, can expand to ninety centimetres when fully grown. They are also soft and flexible, and were used for wrapping butter in the days before refrigeration. Almost all instances in Ireland are male, so the species can spread to new territories only by the roots fragmenting and starting new plants. In David Moore’s 1866 flora of Ireland, Cybele Hibernica, butterbur was recorded predominantly around houses and gardens in some regions, suggesting that, although native, some populations are relicts of cultivation. In some countries, a preparation known as Ze339, made from an extract of the leaves, is used to alleviate the symptoms of allergic rhinitis. Research has also shown an extract of the root to be effective in reducing the frequency of migraines.

8th If you take a holiday in a warmer climate during this season, you may notice plenty of birdsong. Sometimes the singers are familiar birds, but the melody and timbre may be slightly different. A Canary Island blackbird, for example, gives a less liquid and more staccato performance than its Irish counterpart. Birdsong can vary from region to region, especially in non-migratory species. Even on a small geographic scale, birds of the same species may have distinct ‘dialects’. This happens when colonies are separated by a mountain, water or other inhospitable terrain. Dialects are learned, with young birds adopting the local versions sung by the neighbourhood males. Females usually respond to males vocalising in their own dialect. With some species, however, they may choose males with different dialects, perhaps to widen the genetic base of the next generation. City birds, meanwhile, may sing at higher frequencies than their country cousins: this allows their voices to be heard above the urban din.

9th The summer snowflake is misnamed, as its flowering period – just starting – is over and done with in May. The lampshade-like flowers on this bulb are roughly similar to those of snowdrops, but they dangle in small groups of three to six on tall, knee-high stalks. There are six identical petals, instead of the snowdrop’s arrangement of three outer and three inner petals. Each white petal is tipped with a lime-green nub. Leucojum aestivum is rare in the wild in Ireland, and only a portion of the population – along the banks of the Shannon and in the southeast – is believed to be native. The other instances are probably garden plants that have jumped into the wider countryside, possibly by seeds travelling along watercourses. The fruits are inflated with air, which allows them to float. Leucojum establishes in moist places such as riversides, marshes and damp meadows. There are large colonies at Inistioge in Kilkenny and Innishannon in Cork.

10th Some garden ponds, ditches and bog pools are wriggling with little black tadpoles. Others are still hosting clumps of gelatinous frogspawn in various stages of development, from the solid black pinheads of eggs to the elongating commas of embryonic tadpoles. Prolonged spells of freezing weather, such as those that sometimes hit this month, can kill off both the eggs and the budding tadpoles. Eggs on the bottom of clumps may survive, if they are floating in unfrozen water. Free-swimming tadpoles may also live, provided that the pond is not sealed with ice long enough to become anoxic (deprived of oxygen). Individual frogs lay only one batch of spawn per year, so the producers of frost-damaged eggs will have no progeny this spring. However, some frogs spawn late, so even in very cold years, there will be tadpoles somewhere. If your pond freezes, place a pan of hot water on top of it, to melt a hole in the ice. Sometimes, floating a ball on the surface prevents the water from freezing overnight.

11th Let us consider the ‘Lent lilies’, as daffodils are sometimes known. In Irish it is lus an chromchinn, the plant with the bowed head. Although it is not native in Ireland, several different daffodil species and hybrids have become naturalised, forming colonies in demesnes and gardens and around old ruins. Some communities are very old: a planting of the scented Narcissus x medioluteus on Killiney Hill in County Dublin has been known for over two centuries – although the increased volume of foot traffic now means that its days are probably numbered. Daffodils are an important forage plant for early bees and other pollinators. Another insect depending on daffodils and other bulbs is the large narcissus fly (Merodon equestris) – much despised by bulb growers. This furry hoverfly, which mimics a small bumblebee, is a harmless consumer of nectar and pollen when an adult. Its immature phase is another matter. The larva hatches from a single egg laid at the neck of the bulb in May or June. It tunnels into the bulb’s interior and chomps through the tissues, spending months steadily munching away and leaving behind its excretions of gooey, brown frass. In early spring, the larva moves to the adjoining soil, pupates for a few weeks and then emerges as an innocent hoverfly.

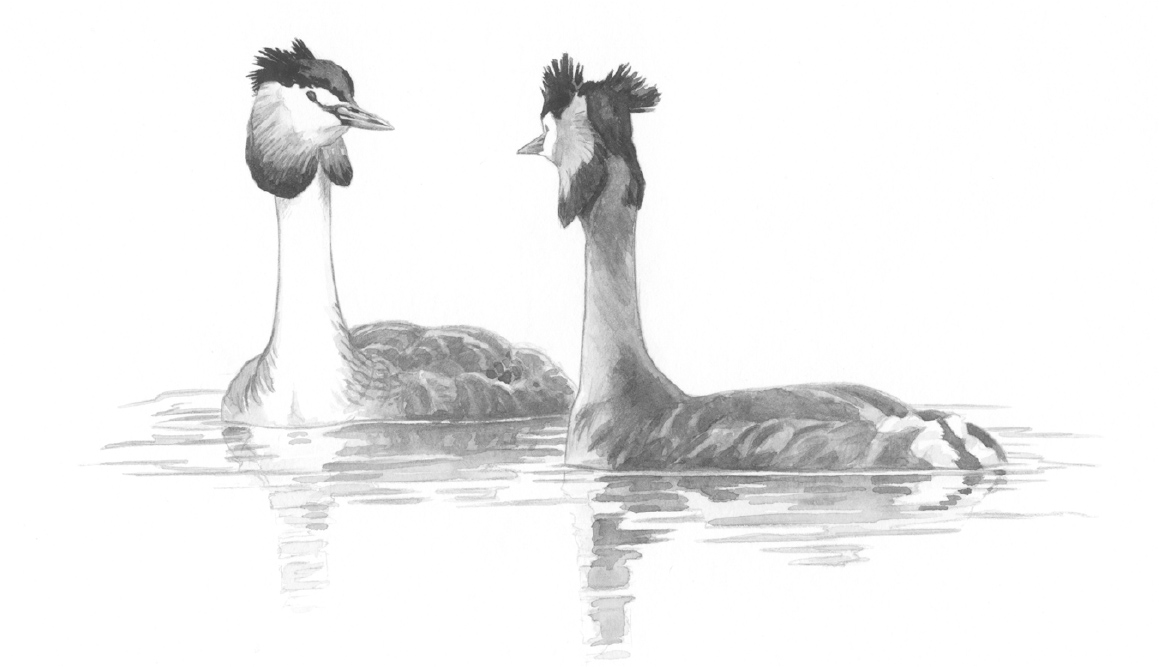

12th In its winter plumage the great crested grebe is an almost puritanical-looking bird, quietly dressed in grey, white and buff. Its dark head plumes, however, jauntily backswept into a quiff, are a hint of the glories that appear now in the breeding season. In spring, the body plumage becomes more richly coloured, and the head and neck are adorned with a double-tufted black crest and chestnut ruff. The birds’ famous courtship display takes place on the lakes, reservoirs and quiet waterways where they will build their nests. With crest and ruff spread tall and wide, a pair dances on the water in a synchronised performance that oscillates between gracefully balletic and energetically slapstick. They head-shake, preen, dip, rise up, tread water, dive and offer each other gifts of waterweed. The nest is a floating platform tethered to vegetation, so that it doesn’t drift away. Demand for the birds’ plumage in Victorian times nearly wiped out the British and Irish populations. By 1860 there were around fifty pairs in Britain. The finely feathered chest skins, known as ‘grebe fur’, were used in clothing, while the head plumes were added to hats.

13th Wood anemones, or wooden enemies, as wits are wont to call them, are in bloom now. Their starry white flowers speckle the ground in mature woodlands and in undisturbed areas in older estates and gardens. Large gatherings are indicators of very old woodland, as the plant spreads at a painfully slow pace, mostly via thin, underground rhizomes, rather than by seed. Clumps are reputed to increase by no more than six feet per hundred years. During rainy or dull weather and at night time, the flowers close up and hang downwards, like minuscule white handkerchiefs. In sunshine they open wide, revealing exquisitely poised golden stamens. Hoverflies and occasionally honeybees visit them. Anemone nemorosa is a spring ephemeral: after flowering, the leaves die back. The plant completely disappears for the rest of the year, its place taken by ferns and mosses. The wood anemone belongs to the same family as the buttercup. Imagine the flowers as yellow instead of white, and the resemblance is clear.

14th Mad March hares are boxing now. They stand on hind legs, batting at each other in quick-fire bouts of frantic, speedy energy. The sparring pairs are usually a female and male, with the former fighting off the attentions of the latter. The bucks are a little smaller than the does: it is possible that the clash is also a test of his strength and stamina. She is more likely to choose a fit and feisty father for her offspring. Our native hare, Lepus timidus hibernicus, is endemic to Ireland (that is, occurring nowhere else) and is a subspecies of the white Arctic hare. Unlike the northern species, the Irish hare does not turn white in winter. Its coat may be anywhere between light brown and dark russet, tones that blend well into our countryside. The Irish hare is found all over our island, from upland bogs to sea level dunes. The greatest numbers are on grassland, such as farmland, golf courses and airfields – including Dublin Airport. The busiest mating season is spring and summer, but breeding can happen all year round. The longer-limbed and longer-eared European brown hare (L. europaeus) has been introduced here several times since the nineteenth century; the two species sometimes crossbreed.

15th Leaves are emerging on some trees, while others are bare. Still others are carrying sere remnants of last year’s foliage, fruits and seeds. Old relics are just as much a part of the tree-scape at this time of the year as new growth. Young beech, oak and hornbeam hold on to their rustling brown leaves until well into spring. Ash is still untidy with bundles of ‘keys’ (seeds): it is the last to leaf up and may be stark and skeletal for many more weeks. Plane trees are adorned with the occasional knobbly seed ball, while on rowan and crab apples a few dried fruits hang – those that escaped the attentions of birds. The great hand-like leaves of horse chestnut are squeezing out of the sticky buds, like lime-green crumpled gloves. In gardens and parks, purple-leaved cherry-plum has been in leaf for over a month and is still sporting dainty pink flowers. On river banks, cascading weeping willows are hazed with green.

16th Sand martins are the smallest of the hirundines that breed here in summer. The others, which share the characteristic bullet body, forked tail and swept-back wings, are barn swallows and house martins. The brown-and-white sand martins are the earliest to arrive, with the first small parties flying in around now. They have spent the winter in Africa, just below the Sahara in the semi-arid Sahel zone. They are faithful to breeding sites, returning year after year to the same locations, which may host colonies of hundreds of birds. Older individuals may return two or three weeks before first-year birds. While this ensures that they can be among the first to set up house in the side of a cliff or quarry, it also puts them at risk from cold March weather. In the coming weeks, pairs will be excavating burrows and lining them with grass and feathers. Despite their petite size, sand martins are adept at digging, shifting heavy stones and other material.

17th There is no true shamrock. Historically, five different trifoliate plants have done service as Saint Patrick’s emblem on this day. The species that is grown commercially is yellow clover (Trifolium dubium), also known as lesser trefoil. It blooms from May onwards with tiny, canary-coloured tuft-like flowers. Its leaves provide food for caterpillars of the common blue butterfly. White clover was another of the shamrocks. In 1726, Caleb Threlkeld notes in his Irish flora:

This Plant is worn by the People in their Hats upon the 17. Day of March yearly, (which is called St. Patrick’s Day.) It being a Current Tradition, that by this Three Leafed Grass, he emblematically set forth to them the Mystery of the Holy Trinity. However that be, when they wet their Seamar-oge, they often commit Excess in Liquor, which is not a right keeping of a Day to the Lord; Error generally leading to Debauchery.

Other plants once used as shamrocks were red clover, black medick and wood sorrel.

18th The wren is the loudest bird in the garden now, declaiming in five-second bursts of clear, trilling sound that end abruptly as if an ‘off’ button has been pressed. The song is both to defend territory from other males and to attract a mate. Despite its great volume, the wren can be difficult to spot, as it is most often surrounded by dense vegetation. Its short, rounded wings are adapted to life in this congested habitat. They allow take-off and other manoeuvres to be accomplished speedily in cramped conditions. Each male builds several nests in his territory (‘cock nests’) and when a female shows interest, he escorts her around his various bits of real estate. One of her criteria is a secluded location, well hidden from potential predators. If she finds a nest that she likes, she adds the finishing touches, bringing in hair and feathers to soften and insulate it. Some males are polygamous, especially in areas where there is abundant food. When they have settled one female in a nest they go off in search of more mates.

19th Moths get bad press, thanks to a few rogues such as the common clothes moth and the codling moth, which is fond of apples. However, of the 1,500-plus species native to Ireland, most do no damage to fabric or food. Some act as pollinators and many provide sustenance to birds and bats and other mammals. Blue tits are just one of the birds that time their broods to coincide with caterpillar season. Several macro-moths – those that are larger and thus easier to identify – are on the wing already. Among these is the beautifully marked emperor (Saturnia pavonia), which belongs to the same family as the silkworm. Males are mostly russet-coloured, while females, which are larger, are more sepia-toned. Both have eye-spots on all four wings, and are decorative enough to be mistaken for a butterfly. Look for them in open, scrubby ground and in hedgerows near brambles, heather and hawthorn – some of the plants fed on by the caterpillars. See mothsireland.com for help with identifying the moths that you find.

20th Cherry laurel is in bloom, holding up slim torches of creamy flower amid large, shiny, leathery leaves. In the past, this native of eastern Europe and southwest Asia was planted extensively on estates for game cover and beautification. By the mid-twentieth century, those well-intended plantings were choking demesne woodlands with evergreen thickets. They marched along, relentlessly sending up new shoots from the base and forming roots where branches touched the ground (processes known as suckering and layering). Bird-dispersed fruits also allowed the plants to jump into the wild. Laurel is now considered an invasive species of high impact, as it shades out native plants and degrades habitats. For non-botanists, it’s hard to believe that this elephantine shrub, with its thick leaves and batons of blossom, is a cherry, but its Latin name, Prunus laurocerasus, signifies its membership of the Prunus or cherry genus. Despite its general undesirability in the wild, it is popular with bees, hoverflies and butterflies, as it produces plenty of nectar. This comes not just from its flowers, but also from nectar-secreting glands (known as extrafloral nectaries) on the undersides of the leaves.

21st Cock pheasants are looking their pompous best for the breeding season. They strut regally with magnificent tails, gleaming blue-green necks, bright-red faces and dazzling white collars. Body and wing plumage is a sumptuous mix of russets and brown with white and dark markings. Males gather a bevy of females, in the same manner as domestic chickens – both belong to the Galliformes order of birds. Pheasants fly only short distances, but they roost in trees at night, out of harm’s way. The hens lay their eggs on the ground in shallow dips, sometimes in the shelter of a bramble or hedgerow. They are not a native species, and are originally from Asia. All those that we see now on roadsides and in parks and woodlands are escapees from shoots, or their descendants. The Romans probably introduced the bird to Britain, but the earliest records in Ireland date from around the sixteenth century.

22nd We have over a dozen native and naturalised species of willow, as well as an array of hybrids. Osiers were often planted in hedgerows and close to houses to provide material for baskets and wickerwork. Such plantings were known as sally gardens: the name is a derivation of the Latin species name, Salix. Most willows are blooming now, although the catkins, as they are known, don’t look like normal flowers. Immature male catkins – pussy willows – are covered in grey fur, which acts as insulation during cold weather. As they mature, they elongate, the stamens protrude, and the copious yellow pollen on the anthers is visible. Willows are wind-pollinated, but they are also visited by bees, which stock up on pollen. Nectar is sometimes produced, and this is a life-saving boost for butterflies emerging from hibernation. The smallest species is the creeping willow, which rarely tops a metre. It grows most often near the coast, on sandy and rocky ground. Look for silvery or silky leaves and little catkins.

23rd Hibernating butterflies sometimes rouse on warm and sunny winter days, but after soaking in a few rays they return to their slumbers. Sunny March days, however, cause surges of butterflies to properly wake up and fly off in search of mates. Peacock, small tortoiseshell, brimstone, comma and red admiral butterflies all overwinter in adult form. The last two have begun to hibernate here only in recent years. Painted lady also attempts to hibernate here, but may not survive. In mild areas the very first of the season’s freshly hatched holly blues may be on the wing. These tiny, pale and luminous butterflies are easy to miss, as they dance in the air some metres overhead and barely stay still. They overwintered as chrysalises on the undersides of the leaves of ivy and various other plants, including bramble. Early summer will see a wave of migrants, including painted lady, red admiral and comma, arriving from abroad.

24th The first of our native hedgerow plants to flower is blackthorn. Its clouds of white blossom billow out from roadside and motorway plantings. The impenetrable thickets of dark twigs – with each shoot ending in a vicious spine – give shelter to the nests of birds, including wrens, blackbirds, thrushes, tits and finches. The leaves provide food for the caterpillars of over fifty different moths. The brown hairstreak butterfly also lays its eggs on blackthorn. The butterfly, which is a rich, rusty orange rather than the brown of its name, is confined to the Burren and a few other places. In autumn, the tremendously bitter sloes, which look like miniature plums, will be eaten by birds and foraged by humans for sloe gin and hedgerow jelly. The stones from sloes picked over a thousand years ago were found in excavations of Viking Dublin. More recently, other parts of the plant were made into folk remedies, while the dried leaves were used as a tobacco substitute. The best-known uses of the wood are for walking sticks and, in the past, for fighting sticks. After the stick was cut it was seasoned in the smoke of the chimney.

25th The dunnock, also known as the hedge sparrow, is a small brown bird. It is not related to the house sparrow, but from a distance it looks similar. It has a slimmer, more pointed bill and more uniform colouring. The dunnock’s manner is careful and diffident, as it shuffles around in the undergrowth, nearly invisible in its sensible, mousy outfit. The Irish-born Victorian ornithologist, the Reverend Frederick Orpen Morris, advocated it as a role model for humans: ‘unobtrusive, quiet and retiring … humble and homely in its deportment and habits, sober and unpretending in its dress…’ Morris was magnificently wrong, for the dunnock’s sex life is so intense that the good reverend is no doubt spinning and blushing in his grave. While a few individuals are monogamous, most dunnocks make complex liaisons involving one, two or even three members of the opposite sex. A ménage à trois of two males and one female is the most common. During the ten-day mating period, starting soon, polyandrous females copulate on average 1.6 times an hour. Females solicit more than one mate because each male who shares paternity of the brood helps to feed her chicks.

26th Young fox cubs are nestled in their dens. In urban areas, vixens may set up house under tool sheds or decking or in an overgrown garden or ruined building. Most cubs are born in March, in litters of four or five. The cubs’ coats are brown when they are first born, and their eyes – which turn a glowing amber as they get older – are blue. Both parents hunt for their offspring, while unmated females born the previous year also often help with care. Rats, mice, nestlings, birds’ eggs and roadkill are all brought back to the den. Back-garden poultry, where available, is a delicacy. The cubs will emerge in the coming weeks, at first staying near the entrance of the den. Later they will play in the open, often stealing balls, plastic plant pots and other items. By the end of the summer they will be able to hunt and forage for themselves.