Полная версия

Filming the Unfilmable

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

FOREWORD TO THE SECOND EDITION

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

INTRODUCTION

1 A FILM IN THE CAREER OF CASPER WREDE

2 COSTINGS AND FUNDING

3 PRE-PRODUCTION

4 FILMING

5 THE BOOK – THE SCRIPT – THE FILM: A COMPARISON

6 RECEPTION

EPILOGUE AND CONCLUSIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SELECTED FILMOGRAPHY AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

APPENDICES

I Casper Wrede’s “Russia on My Mind” and “Letter to a Young Actor”

II Student feedback after the viewing of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

III Mikhail Demin’s drawings for the set

IV Other illustrations

V Staging the Unstageable: Casper Wrede’s Production of Hope Against Hope (1983)

FOREWORD TO THE SECOND EDITION

I first watched One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich as a seventeen year old A-level History student. I had read Solzhenitsyn’s novella, borrowing my teacher’s Penguin paperback copy. Shortly afterwards BBC2 aired the movie. The family had recently acquired a new TV and video recorder from my dad’s redundancy money (this was early Thatcherism and this was the industrial north east of England), so I was able to save a copy on videocassette. Years later, as a university academic specializing in Russian history, I wanted to use movies as a historical source, to give students a visual insight into the knowledge normally acquired through the study of texts. For ‘authenticity’ my inclination was to draw upon Soviet movies through the usual suspects – The Battleship Potemkin (early Soviet period), The Cranes Are Flying (Khrushchev), Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (Brezhnev), and Little Vera (Gorbachev). The exception was this favourite Western cinematic adaptation of a crucial text of Khrushchev’s de-Stalinisation. Despite the English and despite the non-Soviet setting, there is honesty to this dramatization that conveys authenticity. When videocassette was becoming technologically obsolete in the classroom, the university technicians transferred it to DVD. After a chance meeting in Glasgow and an accidental academic conversation about current teaching topics and methods, I lent my copy to colleague Andrei Rogachevskii to use in his own teaching. Subsequently he let it slip that he had gone on to co-author a book on filming the impossible, of which the current text is the second edition.

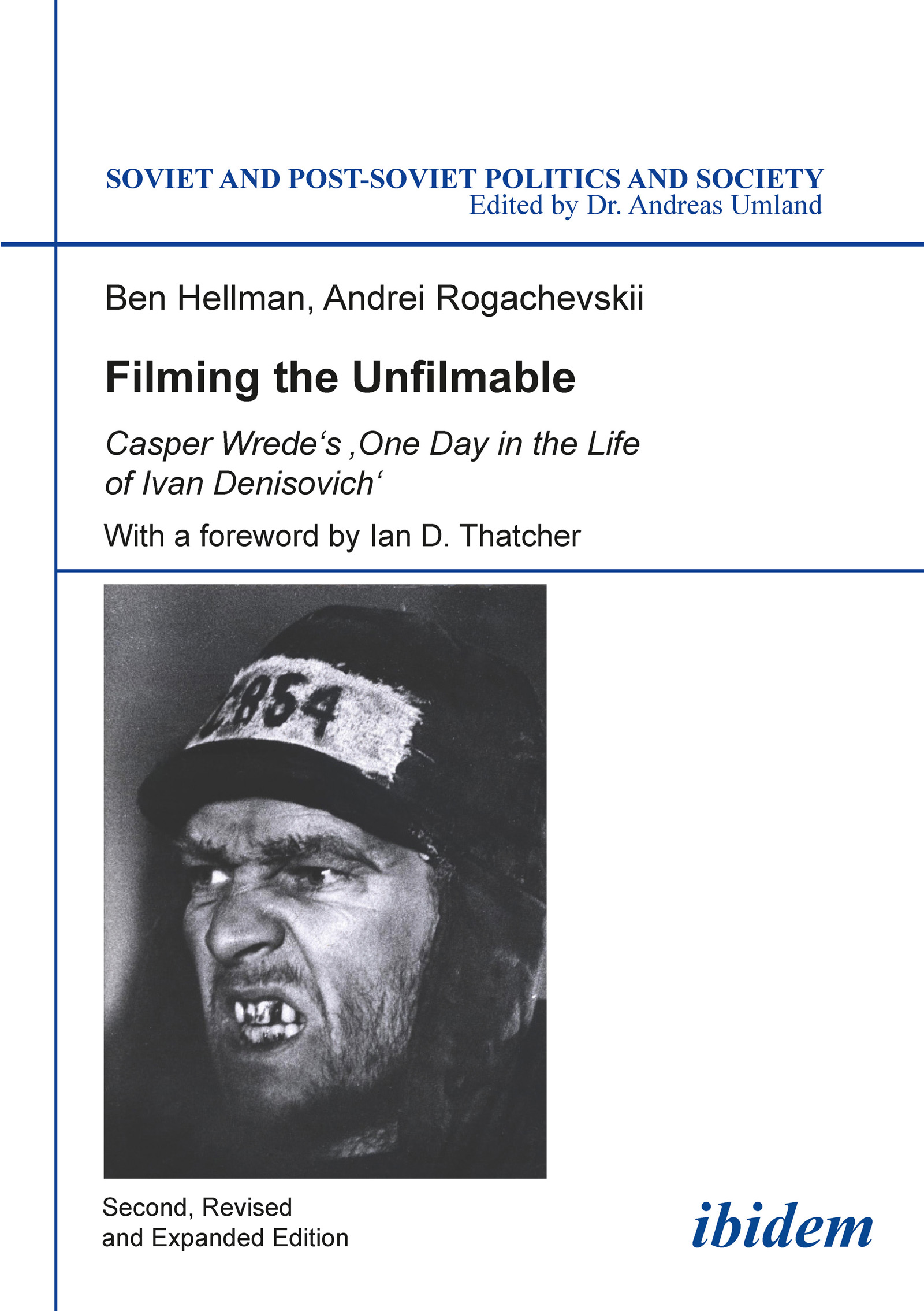

Why does One Day remain, for me, a crucial teaching tool? Why not just use the book? It does not make easy viewing, especially for a younger audience embedded in a culture of fast moving action and instant news. It challenges by its pace, by its silence, by the drama of non-drama. Rogachevskii and his co-author Ben Hellman note that for some critics this left them cold, without a sense of emotional involvement. Exactly – numbness, ambiguity, confusion are appropriate responses. Above all, I show One Day in class because this is a remarkable film that takes a text to a new level of visual art. It speaks directly to the audience as individuals and as a collective about that most difficult of questions: what was life like in the camps? From Tom Courtenay’s narration to the high quality acting in a brilliant and believable set, I defy anyone not to be moved by circumstances in which all, guards and prisoners, are entrapped by life in the camp. Through this movie we feel alternatively the boredom, the drabness, the friendship, the fear, the hope, and the taste of sausage or of tobacco. The editor of Novyi Mir, the Soviet journal that published One Day, praised Solzhenitsyn for encapsulating the contradictions of a complex time in the history of the USSR through well-rounded characters. In this One Day the film more than captures the spirit of One Day the book.

First, it establishes an individual point of view. This is history not as the result of class forces or organisations such as the Communist Party. It is the validity of first-hand experience that is incredibly difficult for us, ‘non-camp inmates’, to question. As Rogachevskii and Hellman point out, Solzhenitsyn felt that the camp was insufficiently realistic – clothes are too fine, prisoners are too well fed. The understandable ex-zek sensitivity will not be shared by most viewers for whom the stark conditions will be apparent.

Second, despite the prominence given to Ivan Denisovich, there is no dominant narrative as there are as many experiences of camp life as there are individuals. Each inmate lives Ivan’s day in his own fashion: one avoids the cells, another ends up in them; one enjoys a comfortable office job and conversations about art, another picks at ice in the open air to help lay the foundations of what will be the People’s Centre for Cultural Activities.

Third, it illustrates the complexity of a range of camp relationships, prisoner-prisoner, prisoner-guard, and guard-guard. There could be collaboration in breaking rules between prisoner and guard, for example, in order to make conditions a little more bearable – as when Ivan is let off punishment for getting up late so that a floor can be cleaned.

Fourth, despite the evidently horrible conditions (barrels as latrines, boiled grass as porridge, cramped sleeping arrangements, and a plethora of rules and regulations), this is a story about life. Death is largely absent; the imperative is to survive and to leave the camps. The arch survivor is Ivan Denisovich, able to take pleasure from building a wall to the extent that he works overtime, risking time in the cells to finish off the last of the cement. The Christian character Alyosha even raises a seemingly impossible consideration: why would one wish to leave the camps for the whirlwind of freedom when in the camps one is free to examine one’s soul? (Saul Bellow reaches a similar conclusion in A Dangling Man).

Fifth, the movie brings out the dilemmas of reform communism. Openness was required and encouraged to face up to the difficult recent Stalinist past. Stalin is linked to the camp system: it is his, not Lenin’s portrait that hangs in the officer’s rest room. That the lies and distortions of socialism Stalin style were an open secret is clear from a prisoner checking the thermometer to see if the temperature is so low that a non-work day would be declared, and a fellow inmate interjecting: ‘Do you think that they would hang one up that gives the real temperature?’ Such talk could produce the system’s downfall. When a supervisor asks Ivan Denisovich why he is laying cement so thinly he replies: ‘Because, citizen, if I lay it on any thicker when the spring comes the whole wall will collapse’. This is the victory of the small man over the bureaucracy. There are limits, though. It is precisely when a commissar’s communist honour is brought into public question during a morning search for ‘illegal garments’ that a harsh punishment is meted out: ‘Ten days in the cells (starting this evening)’. One could say so much more about this movie’s insights into life in a Stalinist camp and how the topic was tackled under Khrushchev. The point to stress is that One Day the movie is not just a historical relic from a Cold War cinematic past. It remains relevant as a celluloid pathway into that past.

Outwith a peculiar and particular Soviet experience, this movie speaks to individual actions and responsibility much more generally and universally. As Wrede himself noted: ‘we are what we do; that is not what we do but how we do it that makes us what we are’. Themes that here are presented in a historical camp context are also relevant in peaceful, ordinary, mainstream society, including the most affluent. One Day is not cheap Cold War rhetoric, for it has challenging and uncomfortable thoughts that transcend political divisions. The key question, repeated twice, is ‘how can we expect someone who is warm to understand someone who is cold?’ When this imaginative leap is taken, when true empathy rules, then one hopes that GULAG camps will not be constructed, that dialogue and charity will replace exclusion and violence in all guises, whether harsh or comparatively mild. This is the essence of a humanistic education. Ultimately and paradoxically, One Day also remains relevant as a hymn to humanism. We should all be grateful to Hellman and Rogachevskii for this fascinating insight into the making and reception of this remarkable filming of the unfilmable. If I were asked to recommend one movie about the camps, this would be it.

Ian D. Thatcher

Professor of History at the University of Ulster

Helsinki, November 2013

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

Since the publication of the first edition of our book, several reviews have come out, aimed at the general public,[1] as well as professional[2] and interest groups.[3] While the reviewers’ appreciation has been rather generous,[4] we would like to use this opportunity to engage with the few instances of criticism.

One reviewer has accurately noted the absence of any theoretical framework in our book.[5] This has been a deliberate decision on our part. ‘Showing instead of telling is what movies are supposed to do’,[6] and in that sense the largely descriptive and meditative nature of Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, coupled with its lack of spectacular action and love interest, does not readily lend itself to screen adaptation. Filming the unfilmable successfully is nothing short of a miracle. Can one really develop a theory of something as exceptional as this?

And what exactly is a success, when it comes to film adaptations? Another reviewer alleges that we have presented ‘Wrede’s One Day as a success due simply to its fidelity to the literary source’.[7] If this is how it looks, it is primarily because Wrede himself had opted to make faithfulness to Solzhenitsyn’s book an integral part of his adaptation strategy. It is probably true that, although used all too frequently by film critics, filmgoers and filmmakers alike, ‘fidelity to its source text <...> is a hopelessly fallacious measure of a given adaptation’s value because it is unattainable, undesirable and theoretically possible only in a trivial sense’.[8] On the occasion, however, it would be unfair not to judge Wrede by his own criteria. As for our own general standpoint on the matter, we are inclined to share Walter Kendrick’s view: ‘it seems self-evident that to film a book is to interpret it, comment on it, violate it perhaps, but not

This quote may serve as our response to the reviewer who has expressed his preference for ‘a clear

On a related issue, another reviewer has wished we would deal more ‘with the failure of the film to connect emotionally with numerous critics’.[12] What is termed here a ‘failure’ may well be rooted in Solzhenitsyn’s original: his fan mail contains both complimentary and reproachful mentions of One Day’s dispassionate manner.[13] Similarly, Wrede’s ‘style of directing was not flamboyant… so what you saw was pretty unadorned when you saw it… [He] wanted the audience to receive what the

The same reviewer observes that we mention ‘the documentary-like feel of the film <...>, but without any exploration of the significance, origin, or even intent of this effect’.[17] Once again, the documentariness originates from Solzhenitsyn’s book. The author was understandably keen to make the GULAG experience a matter of public record. One Day’s first readers, many erstwhile GULAG prisoners among them, called it ‘a truthful document’ and ‘a felicitous snapshot of life in a labour camp’, and challenged anyone to find as much as ‘a modicum of fancy’ in it.[18] It is not therefore too surprising to discover that in the transition from page to screen Wrede retained Solzhenitsyn’s documentary-like approach, just like he tried to keep everything else the book had. Knowing full well that an event has a better chance of surviving in the memory of future generations if it is properly recorded, Wrede presciently did all he could to preserve One Day for the visual age.

Let us return, however, to the issue of a film adaptation’s success. The box office takings aside, it can be claimed that an adaptation is successful if it works as a film, quite irrespective of its relationship to its literary source. Yet one man’s trash is another man’s treasure, and it is not always possible to establish beyond any doubt whether or not a film actually works. An example is Den Første Kreds / The First Circle (1973) by Aleksander Ford, a Danish/Swedish co-production based on another famous book by Solzhenitsyn and released shortly after Wrede’s One Day.

The Polish-Jewish director Aleksander Ford held what might be called a competitive advantage in turning Solzhenitsyn’s The First Circle into a successful film. А forty year long carrier in the film industry had given him the necessary professional skills. As a card-carrying Communist and head of the Polish film production during the first years of Soviet Poland, he had gained quite an insight into the nature of Stalinism. However, in 1968-69, this influential film director and member of the intellectual elite was dismissed from the Polish Filmmakers’ Union, expelled from the Communist Party and forced to leave his country as a victim of an anti-Semitic campaign. His films ended up on the list of prohibited works and his name was wiped out from the history of Polish filmmaking. Outside the Eastern Bloc, he managed to resume his work as a film director, with The First Circle, shot in Denmark, being his most ambitious project, restricted only by financial considerations.

The film’s critical reception upon the 1973 premiere makes a strange reading.[19] An extremely harsh, not to say insulting, tone of many reviews is rather striking. The film is called ‘fairly unforgivable’ (New York Times), ‘a complete shambles’ deserving ‘to be laughed off the screen’ (The New York Daily News), ‘a crime against literature’ (Newsday), а ‘barbarous adaption of the novel’ (Time), ‘an atrocity’ and even ‘crap’ (the New York magazine). It looks as if some critics, anticipating Solzhenitsyn’s negative attitude, took the task of defending the honour of a respected writer, persecuted in his own country and unable to speak up against the attempts by profit-hungry producers in the West to create sensation and make money off his work. Turning a large novel with its many themes and characters into a 100-minute long film was considered a task even more difficult than Wrede’s endeavour. It was a priori doomed to fail both as a work of art and an illustration of Solzhenitsyn’s novel. Consequently, all aspects of the film were seen as disastrous by the distrustful critics.

In their reviews, Ford was accused of turning the book into a flat, static film, lacking in passion and immediacy. The filmmakers’ wish to cover the novel in its entirety resulted in very little of it being left. Solzhenitsyn’s criticism of the Communist system became reductive and his anger nullified. The novel’s characters were moved to a timeless, abstract unreality, with all their features simplified. The descriptive parts of the novel were rendered through pale and lifeless visual devices. Ford also came under attack for filming in colour, instead of black and white. His choice of a multinational cast produced an ‘international mess’ with a tastelessly dubbed dialogue. As a result, spectators watched The First Circle without any emotional engagement.

Nevertheless, there were alternative voices, cautiously ready to accept Ford’s film on its own terms. It packs ‘a considerable punch’, declared Newsweek. The agony was there: it was a passionate cri de coeur against the tyranny of our times. And The New Yorker found The First Circle to be a thoughtful film, forcing cinema audiences to face the same issues that the book had raised. It was ‘an intelligent condensation of the novel’, true to the spirit of Solzhenitsyn’s work, declared Washington Post. The power of accusation was still there (Dagens Nyheter) and Solzhenitsyn’s anti-totalitarian message did come through (Chaplin). Even the cast was praised as talented and apt.

It seems as if The First Circle – in fact, a decent, sombre and respectable film – gains in credit as Solzhenitsyn’s struggle against Communism recedes into history and the audiences no longer seek primarily to compare the book and the film and to judge the latter, first and foremost, by its truthfulness to every aspect of the novel. Phil Berardelli, an enthusiastic cineaste, includes The First Circle among his five hundred favourites, calling Ford’s film ‘a compelling work’, ‘a small movie, but beautifully written and crafted – and making as a point of wisdom that a man who has nothing to lose also has nothing to fear’.[20] And the influential Finnish cinema critic Antti Alanen, who watched the film in 2012 on its Finnish premiere, has found the structure of the screenplay to be successful in its own right. According to him, the film did justice to Solzhenitsyn’s main themes and wit, and its atmosphere rang true, as if personally felt. ‘It’s a memorable movie’,[21] concluded Alanen.

The First Circle can easily serve as an example of how fatally misunderstood some films are. It seems every now and then that all a film needs is a bit of luck. We do hope that, sooner or later, Wrede’s One Day will have its lucky break.

BH, AR

INTRODUCTION

When the Nobel-winning Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn died of heart failure on 3 August 2008, at the age of 89, his legacy was summed up as rallying ‘against all forms of what he saw as spiritual darkness’,[22] although his stance could frequently be characterised as ‘conservative moralising’[23] and was sometimes perceived to be ‘domineering and self-righteous’.[24] Yet all the observers unanimously praised Solzhenitsyn for the role he had played in revealing to the world the nature of the Soviet penitentiary system and the Soviet regime in general. Such revelations had began long before Solzhenitsyn,[25] but only the appearance of his story One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, printed in 1962 by special permission of the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev as part of his policy of de-Stalinisation, managed to capture the attention of a broad cross-section of readership across the globe. The story has been labelled a ‘sensation’ by The Times, The Guardian and The New York Times,[26] and one reader called it ‘a Day that shook the world’.[27] In December 1963, as a sign of its wide recognition in Solzhenitsyn’s native country, the Novyi mir magazine and the Central State Archive for Literature and Art (TsGALI) nominated One Day for a Lenin Prize, one of the Soviet Union’s most prestigious annual awards. However, with the deposition of Khrushchev in 1964 and a moderate re-Stalinisation under Khrushchev’s successor, Leonid Brezhnev, the ‘hard-liners, who feared that Solzhenitsyn had opened a Pandora’s box from which the evils of the Soviet system would escape and sweep the regime away’,[28] did everything within their power to block the author’s further publications in his homeland. Solzhenitsyn’s two major novels, The First Circle (1968) and Cancer Ward (1968-69), came out in the West without the required permission of the Soviet authorities. In November 1969, he was expelled from the Soviet Writers’ Union, and in February 1974, after the publication in December 1973 in Paris of the first volume of his non-fictional Gulag Archipelago – called by the American statesman George F. Keenan ‘the greatest and most powerful single indictment of a political regime ever to be levelled in modern times’[29] – was deported from the Soviet Union ‘for the systematic execution of actions incompatible with Soviet citizenship and harmful to the USSR’,[30] to return only in 1994.

In all these and subsequent years, even The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn’s three-volume opus magnum on political repressions in Soviet Russia in 1918-1956, could not fully surpass One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in importance, possibly because the latter, a slender book in an easily accessible fictional form, seems to contain in a nutshell most of what the average reader needs to know about life in a Stalin’s labour camp and, at the same time, generates a universal appeal by serving as an ‘affirmation of man’s will for survival and his capability of achieving and maintaining dignity under almost unbelievably inhuman conditions’.[31] One Day’s lasting significance was re-emphasised by the decision of the BBC Russian Service to mark the twentieth anniversary of the book’s publication by broadcasting its entire text, read by the author, to listeners in the Soviet Union, on a short wave frequency. In his interview with the journalist Barry Holland that accompanied the broadcast in November 1982, Solzhenitsyn compared the publication of One Day in the Soviet Union, which had occurred thanks to a collaboration of several outstanding personalities and a conflagration of improbable circumstances, to a situation when objects would start lifting off the ground, or cold stones would become red-hot, for no apparent reason, defying the laws of physics.[32] In his later memoirs, recalling how he was recording One Day for this broadcast, Solzhenitsyn talked, perhaps immodestly but not inappropriately, of sensing the story’s timeless nature.[33] A recent Swiss article reaffirms this sensation, well familiar not only to One Day’s author but to many other people, by quoting the Soviet literary critic Vladimir Lakshin, who claimed in 1964 that the story is ‘destined to a long life’.[34]

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was written in 1959, revised and submitted for publication in 1961, first published in the November 1962 issue of the Novyi mir literary magazine[35] and then appeared as a separate edition in the Roman-gazeta series (no. 1, 1963) and under the imprint of the Sovetskii pisatel’ publishers (also in 1963). Ten years later, its full, uncensored version – known as the ‘canonical’ one[36] – was issued in a book form in Paris by YMCA-Press. By 1973, One Day was translated into more than thirty languages, including Afrikaans, Albanian, Bengali, Chinese, Hebrew, Icelandic, Malayalam and Slovene (with at least two different translations available in Czech, Italian, Korean, Portuguese, Swedish and Turkish; at least three, in German; at least four, in Greek; and at least five, in English, German, Japanese and Spanish).[37]