Полная версия

Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Cold War Icon, Gulag Author, Russian Nationalist?

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Dedication

In loving memory of my grandfather, Teodoro García (1921-2013)

Foreword

Acknowledgements

1. Introduction

1.1 The Goal and the Scope of the Study

1.2 Review of Research Literature on the Subject

1.3 Theoretical and Methodological Background of the Project

2. Solzhenitsyn as a Writer and a Witness

2.1 The Style and Genre of Solzhenitsyn’s camp-related Literature

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

The First Circle

The Gulag Archipelago

2.2 The Experience behind the Text: Camp Literature and Witness Literature

2.3 The Reception of Solzhenitsyn’s Camp Literature

2.4 Chapter Conclusion

3. Solzhenitsyn’s Oeuvre between Aesthetics and Politics

3.1 Introduction to Methods and Contextualization

3.2 Anti-communism: Solzhenitsyn at the Heart of the Cold War

Solzhenitsyn’s Reception during the Cold War

Solzhenitsyn in Brandt’s Germany

Solzhenitsyn in 1970’s Britain and the US

Solzhenitsyn’s Late Cold War Reception

Solzhenitsyn’s Reception upon the Collapse of European Communism

3.3 Solzhenitsyn in Revisionist Debates

Introduction

Revisionism in Solzhenitsyn’s Work and Reception

Solzhenitsyn and World War II

Solzhenitsyn and Russian Nationalism

Solzhenitsyn and “the Jews”

3.4 Political Christianity

3.5 Comparative Chapter Conclusion

4. Solzhenitsyn in History

4.1 Solzhenitsyn and Historiography

4.2 Solzhenitsyn and Memory Culture in East and West

4.3 Chapter Conclusion

Conclusions

The Ethic

The Political

The Aesthetic

Concluding Thoughts

Bibliography

A SALAMANDER IN PERMAFROST?

Without Solzhenitsyn the world would hardly have been the same—but does the changing world still need him? As Elisa Kriza’s book demonstrates, the answer often depends on where and who you are and which part of the author’s legacy you prefer to focus on.

In Russia, Solzhenitsyn’s works defeated the Soviet ban, have (re-)entered the school curriculum and are being staged and televised. His Dictionary of Linguistic Expansion (1990)—a quixotic attempt to save underused Russian vocabulary from oblivion—has recently gone into a third edition. The Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia, in operation since 2010, can be seen as a partial implementation of Solzhenitsyn’s 1990 manifesto Rebuilding Russia, which advocated fostering ties between Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine; and suggestively noted the share of Southern Siberia and the Ural Mountains in what Kazakhstan consists of. His film scripts about a Soviet car mechanic (The Parasite, 1968) and the Kengir uprising (Tanks Know the Truth, 1959) are perhaps the only substantial pieces that remain unwanted, possibly because of their high production costs.

As far as the West is concerned, with communism in retreat, Solzhenitsyn is no longer a household name as one of the doctrine’s most iconic detractors and victims. The general decline of the readership in our increasingly visual age is probably affecting Solzhenitsyn more than other authors, because the average length of his books appears prohibitive even to those appreciably intrigued by his controversial (or maybe misunderstood) views on Nazism, homosexuality, Western democracy, and the role of Jews in Russian history (all of which are discussed in Kriza’s study). Anybody who has read Solzhenitsyn’s unfinished Red Wheel epic, about World War I and the Russian Revolutions of 1917—in its entirety, in ten volumes, up to 800 pages each—may well deserve a monument.

Of Solzhenitsyn’s relatively shorter fiction, his 1962 novella about Soviet labour camp experience in the early 1950s, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (his arguably best known and most impactful title), is frequently perceived to be of purely historical significance, while his novel Cancer Ward (1967) is likely to gain following among cancer patients and their friends and relatives, given that the number of cancer cases across the globe, now at approximately 14 million annually, is expected to rise twofold over the next two decades. Solzhenitsyn’s memoirs about his life in the West, The Grain and the Millstones (1998-2003; a sequel to the 1975 USSR-based The Oak and the Calf), are bound to cause quite a stir when they are translated into English—but they have not yet appeared as a separate edition even in Russia, although more than ten years have passed since the last instalment in their serialization (the delay may have been caused by some potentially litigious content).

According to Kriza, Western academia may have a role to play in helping Solzhenitsyn retain some form of public interest beyond Russia, especially if his reception is regularly mediated by recourse to various literary theories (as opposed to judgements dictated largely by political stances and affiliations). All in all, it is not easy to speculate if Solzhenitsyn’s Western reputation as a credible artist-cum-prophet would rebound any time soon, or, to use his own image from the preface to The Gulag Archipelago, his ideas would stay well preserved, like a salamander in permafrost, hoping to impress distant future generations. Meanwhile, in 2012, as a testimony to Solzhenitsyn’s lasting relevance, the Council of Paris voted (against the objections from the Left) to name a city square in his honour. This may or may not be an encouraging sign.

Andrei Rogatchevski

Professor of Russian Literature and Culture

University of Tromsø, Norway

Acknowledgements

This book is based on the doctoral research I conducted as a fellow at Aarhus University. First of all, I would like to thank the Faculty of Arts for the generous stipend that made this project possible. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor Karen-Margrethe Simonsen of the Section of Comparative Literature for her valuable advice and her helpful comments on my text. I also thank my co-supervisor Henrik Kaare Nielsen, and the members of my PhD defence committee—Svend Erik Larsen, Galin Tihanov, and Anja Tippner—for their insightful observations on my thesis. I would like to express my gratitude to Andreas Umland, the editor of this series, and ibidem-Verlag for the opportunity to publish in a series I have long been a fan of. I thank Andrei Rogatchevski for his detailed reading of my manuscript and for kindly contributing the foreword of this book. I would also like to thank Victoria Gosling, my proof-reader, for her good work. I am very grateful to my husband, Thomas, for his unwavering support and encouragement (not only) while I worked on this project.

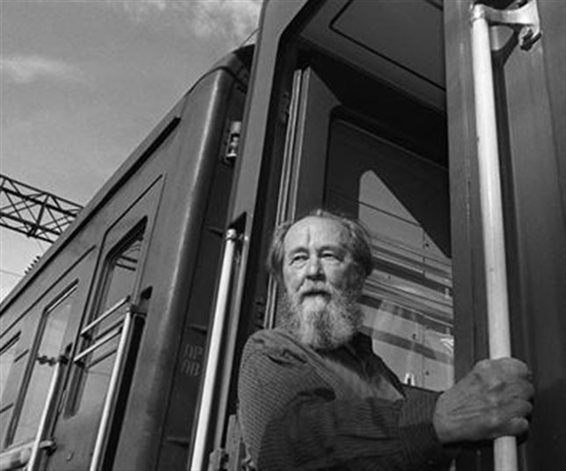

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Russian writer and Nobel prize winner, looks out from a

train, in Vladivostok, summer 1994, before departing on a journey across Russia.

Photo by Mikhail Evstafiev.

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

1. Introduction

1.1 The Goal and the Scope of the Study

In this book I analyze the reception of the Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn in three Western countries: the US, the UK, and the Federal Republic of Germany. My goal is not a quantitative study of Solzhenitsyn’s reception in its entirety but a qualitative analysis under specific perspectives. I investigate the role of the historical and political context in Solzhenitsyn’s reception and its effect on the canonization of his works. Furthermore, I propose new critical readings of his work from a contemporary viewpoint.

The end of 2013 marked exactly forty years since a Russian émigré publisher in Paris printed the first edition of Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago. The apex of Solzhenitsyn’s world fame is now a few decades behind us. What makes a study of his reception relevant today?

Studying the reception of this author is relevant both in a particular sense and more generally. First of all, the results of this study have broader significance because the process of Solzhenitsyn’s international canonization is associated with his status both as a victim of state violence and as a dissident—and this is not unique to the Soviet case. Identifying different canonization mechanisms operating in his reception will give insight into the influence of political, humanitarian, and/or ethical criteria in the assessment of literature under similar circumstances.

Furthermore, Solzhenitsyn is a Nobel Prize winner, and he is an author often described as one of the most significant writers of the 20th century. He has a vast international reception which has received scant attention, making a new and updated study necessary. It is therefore relevant to study the reception of one of the Cold War’s most iconic authors in itself.

Out of the hundreds of dissident writers in Russian history I have chosen to focus on Solzhenitsyn because political dissent has been more central to his reception than it was in the case of other politically troubled authors, such as Alexander Pushkin, or Joseph Brodsky. In my book, I will explore why this aspect of Solzhenitsyn’s work is so central, and why his reception seems much more ample than that of similarly politicized writers such as Andrey Sinyavsky.

Solzhenitsyn belonged to the generation of dissidents who enjoyed a period of cultural freedom during the Khrushchev era (1953-1964), only to be persecuted in the more restrictive environment under Brezhnev (1964-1982). In 1974, he was forced into emigration like many other dissidents. For twenty years he belonged to the Russian Diaspora and émigré culture. Widespread Western interest in the Soviet dissident movement of the late 60s and 70s welcomed him and gave his work an international platform. Because of both foreign interest in dissidents, and his forced exile in the West, Solzhenitsyn became an international object of research and journalism. A foreign gaze focused upon Solzhenitsyn and his work is bound to offer different perspectives than a Russian observation would. In this book I analyze what it was that sparked special interest in the author, but also delve into possible misunderstandings and misrepresentations relating to him. I also take a look at Solzhenitsyn’s place among émigrés and the type of conflicts that arose from his peculiar position.

The time scope of this study will begin with Solzhenitsyn’s first work, which was published in 1962, and end shortly after 2008, the year of the author’s death. This will allow a contrastive analysis of his reception both before and well after the end of the Cold War. The temporal distance from the crest of Solzhenitsyn’s Western reception makes both a diachronic as well as a synchronic approach more accessible. The fact that Solzhenitsyn passed away and that the corpus of his work is now complete makes it feasible to follow the ups and downs of his reception within the context of his entire oeuvre.

As opposed to earlier reception studies of Solzhenitsyn’s work, I not only analyze his reception but also examine aspects of his work it relates to. Solzhenitsyn’s texts have a characteristic ambiguity in genre and authorial voice that had an often neglected impact on their reception. As I will show in this book, this is central to the interpretation of his reception. The parallel presentation of reception and the problematization of key aspects in Solzhenitsyn’s oeuvre will allow me to map the various ways this author has been read, but also ways he has not been read. Areas of emphasis and neglect are both very telling with regard to the workings of Western criticism.

In my study, I will update the discussion on Solzhenitsyn by drawing on recent developments in three areas of study: witness literature, politics and aesthetics, and the role of literature in historiography and memory culture. The structure of this book will reflect these three areas. This is a new and modern approach to the topic that will contribute to contemporary theoretical debates on a general level.

Two core chapters—chapters two and three—build the body of my reception analysis. Chapter two is defined by the theme of witness literature,[1] and starts with an analysis of the genre and style of Solzhenitsyn’s prison camp-related works One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, First Circle, and The Gulag Archipelago. These three works are worthy of special attention for two reasons. The most obvious one is that these are Solzhenitsyn’s most influential books. Additionally, it is because of their subject matter—the prison camp experience—that close attention needs to be paid to their genre and authorial voice. Because Solzhenitsyn was a survivor of the Soviet prison camps, the reception of the connection between fact and fiction in these works is particularly complex. I therefore begin this chapter with an introduction of the style and genre of these three works, and discuss the authorial voice in them. This is a key foundation for later discussions of different forms of reception. I then elaborate upon the relationship between the authorial voice used in these works and their genre, and reflect on the way this can be integrated into theoretical ponderings about witness literature and camp literature. Many scholars who have written about these works emphasize their character as testimonial texts and theoreticians of witness literature and camp literature consider them to belong to these genres. In section 2.2 I will bring these two—very similar—genres into a dialogue about Solzhenitsyn’s work and its reception. In this way, I will clarify if these works can be best understood as witness literature, if the theoretical foundations of these forms of literature are adequate to analyze the complexity of the works they refer to and I will adumbrate how camp literature and witness literature differ from each other. I thus acknowledge one of the most salient features of Solzhenitsyn’s reception—the emphasis on his status as a witness of the Soviet camps—and contrast different understandings of what this implies. Solzhenitsyn was not the first author to touch on the subject of the Soviet prison camps, but he became the most well-known author to do so. What arguments were used to mark out his testimony as better, or as more important than that of other former victims of repression in the USSR? What made his texts stand out in the perception of Western critics? Section 2.3 looks into these questions.

The interaction between aesthetics and politics in Solzhenitsyn’s reception define the outline of chapter three. The central question is, what are the main types of political readings of Solzhenitsyn’s work, and how do they relate to his work? As some of Solzhenitsyn’s texts were relevant to diverse debates I do not build the chapter around his texts, but around the common denominator of these debates. The framework of the chapter takes into account the socio-political particularities of each of the countries of my study and their divergent readings of Solzhenitsyn’s work.

Having achieved fame at the peak of the Cold War, Solzhenitsyn’s work stood in the midst of political debates until the collapse of the Soviet Union. His first text was published weeks after the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, and he was sent into exile while détente and Ostpolitik were leading the headlines. The rise of conservative and neo-conservative movements in the 1970s and 80s is a further aspect that affected Solzhenitsyn’s reception. Yet, how central were directly political arguments in the appraisal of Solzhenitsyn’s work? How far did his influence in political discourse go? How did this change after 1991? The most prominent of the political readings of Solzhenitsyn’s work is anti-communism. I begin my chapter by scrutinizing his reception in anti-communist debates in the Cold War and its aftermath in section 3.2. Less encompassing, but more controversial topics follow. Section 3.3 introduces the phenomenon of revisionism in Solzhenitsyn’s work and looks at examples of these quantitatively vast—yet marginal—readings. Solzhenitsyn’s nationalism as well as his portrayal of World War II and Jews have long been the cause of unease among some liberal readers, but have made the author a standard reference for extremist groups and right-wing scholars. However, because much of this reception takes place outside academia and mainstream media, it has not been the most influential. This explains the short space dedicated to this subject. Lastly, in section 3.4, I discuss readings of Solzhenitsyn that focus on the role of Christianity in politics and society. Several Christian scholars have written numerous books inspired by Solzhenitsyn’s Christian thought. Although this ideological perspective remains peripheral, it is an area in which Solzhenitsyn continues to be avidly read and written about.

In this extensive chapter I show dominant political perspectives emphasized in Solzhenitsyn’s reception, and also sketch some of the topics that are commonly relevant in literary criticism but have been neglected in this particular case. In doing so, I propose possible causes for this selectivity.

In the fourth chapter, I will discuss the role of history in Solzhenitsyn’s work and reception. Most of Solzhenitsyn’s works present historical topics in an innovative and/or peculiar manner, and they have influenced the way scholars write about Russian/Soviet history in the past. For those readers not familiar with historiography of Russia in the West, it may come as a surprise that works like Solzhenitsyn’s novels, novellas, and life-writing have been used as factual sources by different historians. At relevant moments in this book, I discuss the consequences of reading Solzhenitsyn as a factual source. In this chapter, I sum up the problems related with historiographical readings of his work, and propose a constructive way of dealing with history in Solzhenitsyn’s oeuvre by redefining it as a form of memory culture. I will explore this subject while taking into account new developments in the study of historiography, and recent changes in source criticism. Furthermore, this chapter elevates the analysis to a meta-level by appraising the role of Solzhenitsyn’s work and his persona as a part of memory culture in East and West. By drawing from the findings of modern memory theorists, I contrast the meanings attached to Solzhenitsyn in the countries of my analysis and in Russia, and how these have evolved in the last decades. I also argue for the benefits of analyzing the dissident within the methodological framework of memory studies.

The core sources in my project are reviews, articles, and books written about Solzhenitsyn’s works. I focus on the reception of scholars and prominent publicists in the UK, US, and the Federal Republic of Germany. Confining my attention to scholarly and publicistic reception allows me to make meaningful conclusions about influential forms of reception, the development of literary criticism, and the appraisal of literary works in aesthetic and/or political terms as expressed in this paradigmatic case. Although I do include certain controversial scholars and authors, I have decided to exclude authors from the extreme edges of the political spectrum.[2] Because of their peripheral nature their inclusion would skew the results of my research.

Solzhenitsyn’s reception is vast, thus creating the need to set boundaries in its study. I have decided to focus on three influential Western countries:[3] the United States, the Federal Republic of Germany, and the United Kingdom. All three countries had a dynamic relationship with the Soviet Union that affected the way they related to its dissidents. At the same time, these countries have held a lively tradition of cultural exchange with Russia and of studying its literature in specialized institutes and departments in many of their universities. During the Cold War, the US represented the polar opposite to the USSR and it was therefore compelling to include this country in my reception study: no other place embodied anti-communism more vividly than the US and no other dissident represented anti-communism more famously than Alexander Solzhenitsyn. The US was also the country that hosted Solzhenitsyn for nearly twenty years. In the US, Solzhenitsyn continued writing and publishing, and he made important public appearances, such as his famous Harvard Address (1978).

As Solzhenitsyn’s obituaries in the US and Britain show, he is remembered as someone who brought the gulag to the world’s attention. My choice of including the Federal Republic of Germany was based in part on the fact that the knowledge of the gulag there was not new by the time that Solzhenitsyn was writing about this subject. Hence, including a country in my study where this topic did not have the same novelty effect adds more nuance to my research. Furthermore, Solzhenitsyn’s entire oeuvre was translated into German, including books that have remained unpublished in English. The availability of a wider variety of his works in German has also led to a more diverse form of reception, which is interesting in its own right. The effects of the Cold War in Germany awakened a special interest in Solzhenitsyn in the Federal Republic: his claims about what went on behind the Iron Curtain were of particular concern to a divided country. Solzhenitsyn’s relationship to US and German intellectuals remained strong throughout the years. This influenced the continuing public interest in Solzhenitsyn in the US and West Germany.

In the United Kingdom, Solzhenitsyn was part of discussions about communism and how Britain was to relate to the USSR. The scholarly and intellectual relationships between the US and the UK are at times so close that some of the scholars who wrote about and promoted the knowledge of Solzhenitsyn’s work moved from one country to the other, making an inclusion of the UK in my study indispensable. At the same time, the inclusion of Britain prevents a possibly misleading pattern from arising that would be caused by the juxtaposition of merely the US and German reception. Similarities and differences in reception are not easily explained as “European” or “American” peculiarities, but are rooted in both the historical and cultural environment in which they develop as well as the political circumstances and diplomatic ties these countries had with each other.

A further country lurks in the background of this study, and that is, of course, Russia (i.e. the USSR). Very often Solzhenitsyn’s Western reception reflects the way he is read (or not) in his own country, but above all, the rejection or acceptance of the author by his government had a considerable influence on his early readership. The exceptional conditions under which Russian literature developed in the 20th century complicate the question of how and why an author was read. In my study, I introduce a glimpse of Solzhenitsyn’s Russian reception when it relates to that of the countries I discuss. The examination of convergences and divergences of Solzhenitsyn’s reception in East and West can allow local priorities to percolate. I do not study all of Solzhenitsyn’s reception in Russia because of its highly desultory character: Solzhenitsyn was only published in the USSR in the early sixties, late eighties and early nineties. Soviet reception did not develop freely or in parallel to the Western one.