Полная версия

Don't You Cry

I start climbing the steps of Ingrid’s wide, white front porch, and that’s when I hear the high-pitched squeal of a squeaky door hinge, followed by the slamming of a screen door from the home next door, a blue cottage converted into an office for Dr. Giles, the town shrink. It’s been less than a year since he moved his practice in. As I peek over, there he stands in the doorway, saying goodbye to a patient before peering up and down the street—hands in pockets—as if waiting for someone else to appear. Does he hug her? I’m quite certain he does, an awkward one-armed hug not meant to happen in plain sight. That’s what makes it weird. He checks his watch. He looks left, he looks right, up and down the street. Someone is late, and Dr. Giles doesn’t want to be kept waiting. He seems miffed that he has to wait. I see it in his squinty eyes, in his vertical posture, in the way his arms are crossed.

I don’t like the man one bit.

The patient who leaves thrusts a hood up over her head, a fur-lined hood on a thick black parka, though whether it’s for warmth or privacy, I can’t say. I don’t know. I never do see her face before she scurries away, down the street the other way. I don’t see her, but I hear her. Half the town hears her. I hear her crying, a distraught wail that can be heard a half block away. He made her cry. Dr. Giles made the girl cry. Add that to the list of reasons I don’t like the guy.

There was a whole scandal when Dr. Giles moved his office into the tiny blue cottage. A scandal because the ladies in town took to lurking around the café, to puttering up and down the street, so they could see the comings and goings of Dr. Giles’s clientele: which of the town’s members was seeing the headshrinker and why. Proving what people hated most about small-town living: there is no such thing as privacy.

Ours really is the paradigm of a small town. We’ve got one stoplight, and we’ve got a town drunk and everybody knows who the town drunk is: my father. Everyone gossips. There’s nothing better to do than throw one another under the bus. And so we do.

Ingrid opens the door before I knock. She opens the door and I step inside, wiping my shoes on the woven floor mat. She smiles. Ingrid is about the same age my mother would be if my mother were still here. Don’t get me wrong, my mother’s not dead (though sometimes I wish she was dead), she’s just not here. Ingrid has one of those short hairdos forty-or fifty-year-old women sometimes have, the color of wet sand. She has welcoming eyes. She has a nice smile, but a sad smile. There isn’t a person in town who could say a bad thing about Ingrid, but rather the bad things that have happened to Ingrid. That’s what they talk about. Ingrid’s life is the definition of tragic. She’s gotten the short end of the stick, that’s for sure, and as a result she’s become the town’s charity case, a fifty-year-old woman too terrified to step foot out of her own home. She has panic attacks any time she does, chest pressure, trouble breathing. I’ve seen it with my own two eyes, though I don’t know her whole story. I make it a point not to meddle in others’ business, and yet I’ve seen Ingrid get loaded into an ambulance and whisked off to the emergency room when she thought that she was dying. Turned out everything was fine. Just fine. Just an ordinary case of agoraphobia, as if it’s ordinary for a fifty-year-old woman to stay in her home because she’s scared to death of the world outside. She doesn’t leave her house for anything, not to get the mail or water a flower or pick a weed. Within the gypsum walls she’s perfectly fine, but outside these walls is another story.

But all that said, Ingrid isn’t crazy. She’s about as normal as they come around here.

“Hi, Alex,” she says to me, and I reply, “Hi.”

Ingrid dresses like a fifty-year-old woman should: a bright orange sweatshirt kind of thing, and black knit pants. Around her neck, a locket and chain. In her earlobes, stud earrings. On her feet is a pair of flats.

Before Ingrid has a chance to close the door, I turn around for a quick peek. There in the storefront glass I see her, Pearl, obscured in part by the reflection of nearly everything on the opposite side of the street. What’s inside and what’s outside are complicated by glass, so it’s no wonder that birds fly headlong into it sometimes, plummeting to their deaths on the porous concrete.

But still, through the marquee of trees and in the manifestation of half the world on one pane of glass, I see her.

Pearl.

Her eyes stare out the window, but not at me. I follow the path of Pearl’s eyes to a sign that hangs with scroll brackets from the neighboring home: Dr. Giles, PhD. Licensed Psychologist. And there he stands, Dr. Giles, with his dark, trim-cut hair and well-groomed style, waiting impatiently for a patient to appear.

Well, I’ll be. She’s watching him.

Does she have an appointment with Dr. Giles? Maybe. Maybe that’s it. My perception shifts, but not so much that I stop thinking about her hair or her eyes, because I don’t. In fact, they’re there every time I so much as blink.

Ingrid closes the door, and she asks of me, “Can you lock it?”

Ingrid’s home is on the small size, but more than adequate for a single occupant as I kick the door closed, turn the dead bolt, and bring Ingrid’s lunch to her kitchen table. On the marble countertop is an open cardboard box, a small reserve of novels set beside it. Something to pass time. There’s a knife set there, too, a professional-grade carving knife, used to slice through the packaging tape.

The television is on, a small flat-screen TV that Ingrid doesn’t watch, though I can tell she’s listening to it and my guess is that the sound of actors and actresses on the TV screen tricks her into feeling like she’s not alone. That someone is here even if they’re only make-believe. It’s a spoof she plays on herself. It must be lonely, not being able to leave your own home.

The house is otherwise quiet. Once upon a time there was the sound of boisterous children and stampeding feet, but not anymore. Now those sounds are gone.

“I was hoping you’d do me a favor, Alex,” Ingrid says, drawing my eyes away from a lady on the TV screen. Her home is a crisp white: white walls, white cabinets. The floors are a contrast to the rest of the home, stained plank flooring, so dark they’re almost black. Her furniture and decor are austere, shades of neutrals and gray, not much in the way of knickknacks or accessories, unlike my own home, Pops being the hoarder that he is, unable to part with anything. It’s not like he collects years’ worth of rubbish, piled miles high in the middle of our living room, stray cats procreating in every crevice of our home so that it burgeons with feral kittens, some living, some dead. No, not like that; not like those hoarders on TV. But he is sentimental, the type that has trouble parting with my junior-high report cards and baby teeth. I suppose this should make me feel good. Deep down I guess it does.

But it’s also a painful reminder that Pops has no one else in this world but me. If I were to leave, where would he be?

“I made a shopping list,” Ingrid says, and without waiting for her to voice the words—Will you go?—I say, “Sure thing. Tomorrow, okay?” And she says that it is.

From a window in the kitchen of Ingrid’s home, I’ve got a decent view straight to the inside of Dr. Giles’s office. Ingrid’s Cape Cod sits just above his, the window at the ideal angle to see right in. It’s not a great view, but still, it’s a view. As Ingrid sorts through her purse for two twenty-dollar bills and hands them to me, I catch sight of something shadowy and vague, just the movement of shapes through the glass. Someone is there. I stare, but I don’t stare long. I can’t. I don’t want Ingrid to think I’m some Peeping Tom. Instead, my eyes meet Ingrid’s and I tuck the two twenty-dollar bills into a pocket and tell her that I’ll go tomorrow morning. I’ll go to the grocery store in the morning. I’ve done this routine many times before.

I take the list, say my goodbyes and go.

The minute I emerge from Ingrid’s house and step down the wide porch steps and onto the sidewalk, I see it.

The café window is now untenanted.

The girl is gone.

Quinn

I often thought that Esther was transparent, like a pane of glass. What you see is what you get. But now, sitting on the floor of her boxy bedroom, on my legs so that they’ve gone numb, holding the note to My Dearest in my hand, I think that maybe I was wrong. I’ve gotten it all wrong.

Maybe Esther isn’t transparent, after all. Not a pane of glass but rather a toy kaleidoscope, the kind with intricate mosaics and patterns that change every time you so much as turn the edge.

It was a listing in the Reader that brought me to Esther.

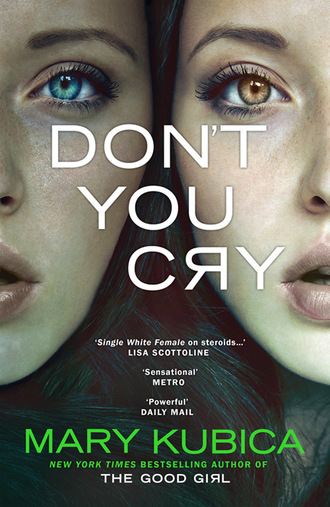

“You can’t be serious?” asked my sister, Madison, when I showed her the ad: Female in need of roommate to share 2BDR Andersonville apartment. Great locale, close to bus and train. “You have seen the movie Single White Female, haven’t you?” she probed from the edge of her twin-size bed, science flash cards spread out before her, proliferating like rabbits on the bedspread.

I picked up a flash card. “You’re never going to need this junk, you know?” I asked, staring at the garbled definition on the back. “Not in the real world, anyway.”

And then Madison gave me that look like she always did and said, “I have a test tomorrow,” as if that was something I didn’t know.

“No shit, Sherlock,” I said, tossing the flash card back on the heaping pile. “But after high school,” I mean. “You’re never going to need this crap.”

I was the last person in the world who should be giving anyone advice on anything, the least of which was education. I had graduated five months ago from college, a crappy college at that, one which didn’t quite make the cut of best colleges in the US of A. But the tuition was cheap, or cheaper than its counterparts. They also let me in, the same of which couldn’t be said for the other colleges to which I applied thanks to a little thing known as learning disabilities. Between the ADHD and the dyslexia, I was a lost cause. Or so said the multitude of rejection letters I received from the colleges to which I applied, with the big, red Rejected stamp across the returned applications.

That’s quite good for the self-esteem. Really, it is.

Or not.

I spent the first two of my eight semesters on academic probation. But when the dean threatened to dismiss me from school, I got my act together and cracked open a book. I also remembered to take my Ritalin from time to time, and admitted to the learning disability, which I wasn’t too keen on having to do.

But still, somehow or other I managed to graduate from college with a 3.0. And yet no one needs academic advice from me, least of all Madison, my little sister, on schedule to graduate with high honors. And so I shut my mouth. On that subject at least.

I had, by the way, seen the movie Single White Female. Of course I had. But desperate times called for desperate measures, and I was desperate. I was twenty-two years old, five months post–college graduation and desperately in need of fleeing my parents’ suburban home where they lived with my mastermind sister and her smelly guinea pig. Madison was still in high school, a science geek with a whole medical career ahead of her. That or an embalmer, maybe, with her whole morbid fascination of things that were dead. She had a taxidermy squirrel she bought on the internet with her allowance, the same thing she planned to do with the guinea pig when it finally kicked the bucket—skin and stuff the pathetic thing so she could set it on a shelf.

Madison was happy as a clam living at home. She couldn’t understand my need to get out. It was more than just dullsville for me; it was nails on a chalkboard, the way my mother’s minivan greeted me at the suburban Barrington Metra station each day after work, Mom behind the wheel, always on my case to know how the day had gone.

Did you make any friends today? she had asked that first day of my new career as a project assistant at an illustrious law firm in the Loop, as if it was the first day of kindergarten and not a job. I got the job based on a little white lie, claiming interest in law school when law school didn’t interest me at all.

Did you learn anything new? my mother asked there, that day, in the front seat of her car.

Nope, Mom. Nothing.

But I did, didn’t I? I learned how much the job sucked.

And then my mother and I drove home, where I was forced to listen to the parental figures go on and on about how Madison was oh so smart, about how Madison aced another exam, about how Madison had already been accepted to some smarty-pants college, while I’d picked one based on the simple fact that it was cheap and they’d actually accepted me as opposed to the mass of rejections I received following a poor performance on my SAT.

I had to get out. I was feeling suffocated, smothered. I couldn’t breathe.

And that’s when it happened. I was riding the Metra home from work when I flipped open to the classifieds and saw the ad in the Reader. Esther’s ad, a beacon in a dark night sky. I’d looked for apartments before, but my entry-level job barely paid minimum wage, and though I tried cutting corners—studio apartments, garden apartments, apartments on the south side—the simple fact was that I couldn’t afford an apartment in Chicago all on my own. And an apartment outside of Chicago was out of the question because then not only would I need an apartment, I’d also need a car, some mode of transportation to drive me to and from the train station rather than mother dearest.

Female in need of roommate to share 2BDR Andersonville apartment. Great locale, close to bus and train.

I was sold! I called immediately and we made arrangements to meet.

The day I was to meet Esther for the first time, I mentally prepared myself for a meeting with Jennifer Jason Leigh. Truth be told, Madison had psyched me out with the whole Single White Female bit. To make matters worse, I watched the movie before our meeting, watched as Jennifer Jason Leigh, aka Hedy, turned all psycho or whatnot, assuaged only in the fact that, as the one moving into Esther’s apartment, I was in fact the Jennifer Jason Leigh in our situation, and she the charming Bridget Fonda.

And indeed she was charming.

Esther was running late that day, held up at work by a coworker who’d called in sick. She phoned as I was heading to the apartment, and we made plans to meet instead at a bookshop on Clark, where I soon found out she worked. Just a part-time gig while she finished up a master’s degree in occupational therapy, she said. She was a singer, too, the type who performed on occasion at one of the local bars. “Just something to pay the bills,” she said, though in time I would come to learn it was more than that. Esther had a secret craving to be the next Joni Mitchell.

“What’s an occupational therapist?” I asked as she led me through the stacks of books to a quieter spot in back and we sat on blood-orange poufs meant for children’s story time, apologizing for dragging me down to the bookshop and veering me away from our original plan. It was a Saturday; the shop was full of cosmopolites, browsing the shelves, picking their books. They looked smart, every single one of them, as did Esther, though in a cool, contemporary sort of way. She was doe-eyed and polite, but possessed traces of an inner devil, be it the sterling silver nose stud or the gradient hair. I liked that about Esther right away. Dressed in a cozy cardigan and cargo pant ensemble, Esther was cool.

“We help people learn how to care for themselves. People with disabilities, delays, injuries. The elderly. It’s like rehab, self-help and psychiatry all rolled into one.”

Her teeth were aligned successively inside her mouth, a brilliant white. Her eyes were heterochromatic—one brown, one blue—something I’d never before seen. She wore glasses that day, though I learned later they were only for show, a prop for her role as book salesman. She said they made her look smart. But Esther didn’t need faux glasses to look smart; she already was.

The day we met, she asked me about my job and whether or not I’d be able to afford my half of the rent. That was Esther’s only qualification, that I pay my own way. “I can,” I promised her, showing my latest paycheck as proof. Five-fifty a month I could do. Five-fifty a month for a bedroom of my own in a walk-up apartment on Chicago’s north side. She took me there, down the street from the bookshop, just as soon as she finished reading to the tiny tots who pilfered from us the blood-orange poufs. I listened to her as she read aloud, taking on the voice of a bear and a cow and a duck, her voice pacifying and sweet. She was meticulous in the details, from the way she made sure the little ones were attentive and quiet, to the way she turned the pages of the oversize book so all could see. Even I found myself perched on the floor, listening to the tale. She was enchanting.

In the walk-up apartment, Esther showed to me the space that could be my room if I so chose.

She never said what happened to the person who used to live there in the room before me, the room I would soon inhabit, though in the weeks that followed I found vestiges of his or her existence in the compact closet in the large bedroom: an indecipherable name etched into the wall with pencil, a fragment of a photograph abandoned on the vacant floor of a hollow room so that all that remained on the glossy image was a wisp of Esther’s shadowy hair.

The scrap of photo I did away with after I moved in, but there was nothing I could do to fix the closet wall. I knew it was Esther’s hair in the photograph because, like the heterochromatic eyes, she had hair like I’d never before seen, the way she bleached it from bottom to top to get a gradual fade, dark brown on top, blond at the bottom. The tear line on the picture was telling, too, the barbed white of the photo paper, the image gone—all but Esther.

I didn’t toss the photo, but rather handed it to Esther with the words, “I think this is yours,” as I unpacked my belongings and moved in. That was nearly a year ago. She’d snatched it from my hand and threw it away, an act that meant nothing to me at the time.

But now I can’t help but wonder if it should have meant something. Though what, I’m not so sure.

Alex

I wait for hours for the girl to return—trying hard to stare through the window coverings of Dr. Giles’s cottage office—but she doesn’t show. I consider sneaking into that space between Ingrid and Dr. Giles’s home, standing on tiptoes to try and see in. I contemplate a return visit to Ingrid’s home—feigning I forgot something, that I needed something—to try and catch a glimpse from her kitchen window. I imagine that Pearl is in there, in Dr. Giles’s cottage, doing what people do in a shrink’s office: sitting on a sofa, spilling her guts to a man who gets his kicks listening to other people’s problems. But then the time goes by—thirty minutes, an hour, two hours—until I tell myself it’s been too long for her to be in there, chatting it up with Dr. Giles. No psychiatry appointment lasts two hours. Or do they? I’m not one to know.

In time, I give up. She’s not in there, I tell myself. But of course I’m not sure. I can only guess.

In the middle of the afternoon, I go home. I retrace the steps I made this morning, down the streets of town, past the small stores that are closing up shop for the night, flipping Open signs to Closed, locking the doors. I’m tired; my feet hurt. My head swims with the image of that girl at the window, here one minute, gone the next.

The streets are paved with setts, rectangular granite blocks like cobblestones. The two restaurants remain open, but the boutique stores—the cutesy one with baby stuff in the front window and the one that carries nothing other than novelty items and a poor selection of cheesy, overpriced greeting cards—will soon close. The streets are sleepy, the gray sky contemplating rain. To the side of the road, there’s a big, black crow feasting on a rabbit carcass: roadkill. Everyone gets a little desperate this time of year. A squirrel scampers across a telephone wire, praying the crow doesn’t see. Down the street a group of preteen boys in shorts and T-shirts walk home, as if unaffected by the cold. The sound of their laughter cuts through the autumn air. One of them puffs on the end of a smoke; he can’t be older than twelve or thirteen.

I pull my hood up over my head. I tuck my hands into the pockets of my pants and walk quickly, head down, through town, past the carousel, and to the beach.

The town is lonesome and I am feeling blue.

I think of my pals Nick and Adam and Percy, off at college, having the time of their lives. Meanwhile, I’m thinking of some girl I don’t even know, may never see again, likely a head case, too.

The lake pounds the shore, no different than it did this morning. It’s only in daylight that I can see the choppy waves out at sea, the steady flow of whitecaps that charge the sand, livid and swift like knights on horseback—a charging cavalry. The sand is a washed-out brown. The lake has a smell to it, not an unpleasant one, but one that just smells soggy and wet and cold. The sand sticks to my black gym shoes as I make my way past the tall beach grass, the dense bursts that emerge through the sand. The grass is brown and brittle now. No longer green. Soon it will be gone, torn from its roots by the cold and the wind and the snow. My eyes rove the sand for crinoid stems—the tiny disks I find in the gravel and in the sand—just as they always do. It’s a fixation for me, a weakness, a habit. Crinoid stems, Indian beads, sea lilies. It’s all the same to me, the fossils of prehistoric creatures that once inhabited Lake Michigan. I gather a crinoid stem from the sand and admire it in the palm of my hand. Much more beautiful than shale or basalt rock to me; much more meaningful than granite or slag, though, really, they’re nothing much to look at. People string jewelry with these, but me, I collect them in a Ziploc bag. For now, I slide it into the pocket of my pants, holding tight, careful not to let go.

There’s a couple out on the pier, a man and a woman, not far out, but far enough to get the gist of it without being knocked into the water by the wind. They hold each other by the hand—steadying one another in the stubborn gale—as they take in the sweeping lake views and the apocalyptic sky, and then they turn and go, trooping to a car parked in the adjoining lot, stomping the sand off their shoes as they do.

But I don’t go. I stay, taking it all in for myself.

It’s only after they’ve left and I’ve watched the black car spin out of the lot and out of town that I see her sitting all alone on the playground’s belt swing, her feet dragging through the sand below. Her hands clutch the chain, though she doesn’t pump her legs, allowing the wind to move the swing for her. It’s a measured swing to say the least, deliberate and lazy, as one does when they’re thinking about something else and not at all about the swing.

Pearl.

Her coat is on; her hat is on. Her hands are ungloved and look to me to be cold. Her scarf is wrapped around her neck, though the wind grabs it by either end and pulls, so that the scarf floats this way and that on the current of the wayward wind. It’s begun to rain—just a slight drizzle—something she seems repellent to, as if she’s waterproof. She doesn’t seem to mind the rain, which pelts me in the eyeballs and soaks my insides. I can’t stand the rain. I could scurry home; I should scurry home. I should run. But I don’t. Instead, I move to a covered spot, a picnic area with wooden tables and, more importantly, a roof. I sit on the timber tabletop, a solid fifty feet from where Pearl sits.

She doesn’t see me.

But I see her.

Quinn

When I get to the end of the note, I have one, simple, undeterred thought: Who the hell is My Dearest? I have to ask Esther about this. I just have to. The last line screams over and over again in my ear: Did you see me? Were you trying to make me mad?