The School for Good and Evil 3-book Collection: The Camelot Years (Books 4- 6)

“Hey, guys?” Nicola interjected.

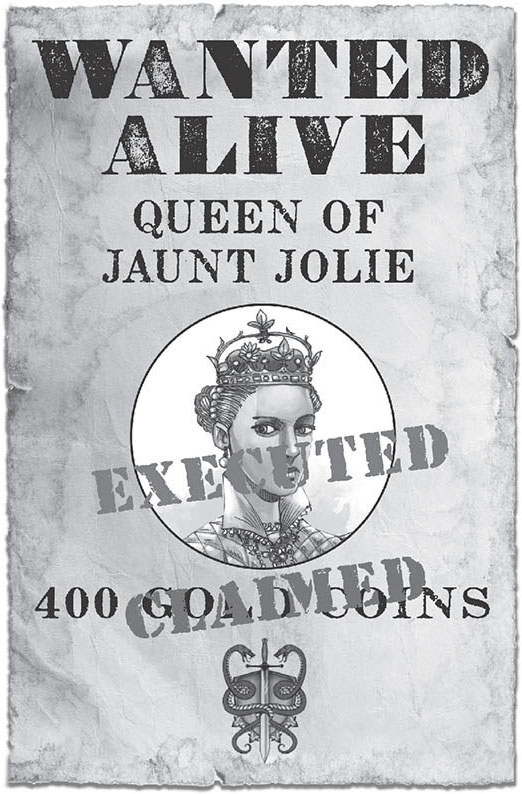

Agatha and Sophie followed her eyes to a tattered poster on the ground.

“He killed a queen?” Sophie breathed.

Agatha knew she should feel scared for her own fate, but looking at the queen’s face, she only felt fury. “What kind of boys would help a masked murderer? They’re just like that scummy beaver. Willing to do anything for a bundle of gold.”

And yet scores of gold coins were littered across the pavilion, as if the scoundrels had earned so much booty that this was merely loose change. Nearby, a young pirate urinated on a wall beneath shops graffitied with new names: “DAMSEL IN ’DIS DRESS,” “YO HO HOME FURNISHINGS,” “THE PEG LEG PUB,” “PLUNDER’S PLUMBING.” And all the while, they sang shanties off-key as they waved cider jugs and stomped their silver-tipped boots—

Underneath me pirate hat,

That’s where I hide me treasure map!

On the deck where floorboards creak,

That’s where I keep me wooden teeth!

In lovely maidens’ open hearts—

That’s where I’m storin’ all me farts!

“No wonder the School Master didn’t take them for Evil,” said Agatha. “Pirates in storybooks are bold and clever. These are just horrible.”

“Wonder if Hort feels the same way,” said Nicola.

“Hort, Hort, Hort. Is that all you talk about?” Sophie moaned.

“Hort’s father was a pirate, which means Hort grew up around pirates,” said Nicola. “He might very well know these boys.”

“Good point,” said Agatha.

Sophie muttered something under her breath.

Agatha wished she could talk to Hort, but he was at the front of the chain, sweaty and shirtless after reverting from a man-wolf (the pirates had thankfully let him put on breeches). The witches were with him too, whispering to each other and giving Agatha nervous looks.

Agatha’s stomach sank. Had she really thought this through? Or had she unwittingly put her crew in danger like she had in Avalon? While sailing from there, they’d all been so busy preparing for the battle against the pirates that Agatha had never prepared for what would happen if they were captured (the pirates had even chained up Hester’s demon). Nor had she or Sophie revealed to the witches what the Lady of the Lake had said. Agatha herself had barely processed what Sophie told her. …

Arthur’s blood? How could the Snake have Arthur’s blood? Was there another relative they didn’t know about? Or did “Arthur’s blood” mean something else? She needed to talk to Professor Dovey about it, but because of that cruddy crystal ball, Dovey wouldn’t check in with them until tomorrow—

Wait. Wouldn’t the Storian have written about it? They were in a fairy tale, after all, where the pen recorded every key moment. Dovey was on watch in the School Master’s tower. … She would have seen the scene unfold between Sophie and the Lady of the Lake … which meant Dovey surely knew what the Lady had said to Sophie before she vanished. And if Dovey knew, so would Merlin … perhaps even Tedros by now. …

Agatha tensed up. Did Tedros know, then, that his best friend was dead? Did he know that his princess was hunting the killer? All her efforts to insulate him from worry suddenly seemed foolish.

And yet, beneath it all, Agatha also felt an odd relief. If anyone could make sense of what the Lady of the Lake had said, it’d be Dovey and Arthur’s own family. She’d leave the mystery in the Dean’s hands for now, then. She had to. Because every part of her had to focus on how she and her crew could meet a murderous villain and still come out alive—

“Aggie, look,” Sophie said, pointing to the royal castle ahead, with two pink-and-gold towers now flying black crossbones flags. It’s where the pirates were leading them.

“Izzat the ‘princess of Camelot’? I’ve seen prettier mole rats,” a handsome young pirate heckled as the prisoners crossed into the pavilion.

“Don’t care if they look like a horse’s arse as long as I git me gold,” a shaved-headed one said. “Tally those bounties, divide by us, and what’s that make?”

“A whole lotta beef,” said a fat pirate, firing up the barbecue to a resounding cheer.

“Blimey. A couple fine ones in there, innit?” grunted a swarthy one, swinging his arm around Nicola.

“And lookie here! The new Dean of Evil!” a runty one hooted, grabbing at Sophie. “Saw her portrait in my sis’s school handbook! Wonder if she’ll let me in for a kiss. …”

Agatha could see Sophie’s finger glowing so pink it was starting to melt the gold vial on her necklace. But even with her cheeks hot with humiliation, Sophie knew full well they shouldn’t fight these thugs. They’d be face-to-face with the Snake soon. …

“Hi-ho! Fair maidens! Sing us a shanty!” the fat pirate yelled.

“Shanty! Shanty!” the boys demanded.

“We need a plan for the Snake,” Agatha whispered to Sophie.

“I have an idea,” Nicola said, eavesdropping.

“We don’t need anything from you, first year,” Sophie grouched.

“A first year who’s saved your life twice,” said Nicola.

“Luck,” Sophie poohed.

“I’ll take any luck we can get,” Agatha trumped to Nicola. “What do you have in mind?”

A spray of gold coins flew over their heads.

“Sing us a shanty!” the fat boy badgered, flinging more gold at them.

“Snake wears a mask, right?” said Nicola, ducking the coins. “He’s not going to want to reveal his identity.”

“Aren’t you glad she’s here, Aggie? So helpful,” Sophie sniped.

“But that’s how we find out who he is,” said Nicola, looking squarely at her. “Sophie, we need you to—”

Someone yanked the line to a stop and the three girls crashed into Willam, who was right in front of them. Sunburnt Wesley glowered down from the horse, his sword blade hooked through the chain. “When a pirate gives ye an order, ye best obey it. Don’t think the Snake would flinch if we delivered yer lot without noses.” He tapped Sophie’s and Nicola’s noses with his sword. “Which means we ain’t movin’ another inch until these two lassies pucker up and sing.”

Sophie and Nicola swallowed.

So did Agatha, Hester, Anadil, Dot, Hort, Bogden, and Willam, finally all able to look at each other again. This wasn’t like the battle on the boat; here they were outnumbered by pirates twenty to one, they couldn’t direct their fingerglows with their hands cuffed behind their backs (Anadil’s rats included), and their best weapon, Hester’s demon, was wrapped in chains, uselessly trapped on her neck. Meaning the future of the crew’s noses depended on the song that was about to come out of the two girls’ mouths.

“I’ll start,” Sophie announced—

“No, I will,” Nicola cut in. She eyed Agatha intently and sang in a clear voice:

“There once was a boy named Ito

Whose tale was in my storybook.

He had a face of perfect beauty

And all day in mirrors he looked.

But Ito loved his face so much

He didn’t want others to enjoy

So he put on a mask

And pretended to be coy

He wore the mask for days and years

Until he fell for a lovely girl

Who confided to a friend,

‘He must be ugly and hiding from the world.’

So Ito finally removed his mask

To prove her wrong and be bold

Only to find that in time

His face had grown very old.”

Agatha lit up with understanding. Looking miffed, Sophie glared at Nicola, then opened her mouth to sing, but Agatha jumped in and sang back to Nicola in a husky, barbarous croak:

“I know a boy like Ito

Who wears a mask of green

We need a pretty girl to tempt his pride

And make him want to be seen.

A girl like a prize or a trophy,

A girl whose name is …”

Agatha and Nicola turned and stared at Sophie.

Sophie blinked back at them, baffled.

Silence hung over the pavilion.

“THAT AIN’T A SHANTY!” a pirate cried.

“Boo!” the others shouted.

Beef bits and fistfuls of coins spewed violently in their direction. Someone threw a parrot and hit Hort in the groin—

“Poke out their eyes!” one ordered.

“Cut off their arms!” commanded another.

Young pirates with swords advanced. Agatha and Nicola recoiled, dragging the rest of the crew with them. There was nowhere to go. All nine members of the group backed up against a wall, shadows of pirate blades rising over them. Fingerglows burnt bright behind the kids’ backs as they tried to melt each other’s cuffs. … Hester’s demon screeched and tore at his chains. … But it was too late. Swords slashed down—

“Yoo-hoo! Boys!”

Hands behind her back, Sophie shimmied her ruffly blue dress and started high-kicking—

“I’m Whiskey Woo, the pirate queen!

Whiskey Woo!

Whiskey Woo!

I’m Whiskey Woo, the pirate queen!

Whiskey Woo!

Whiskey Woo!”

Pirates held their swords, eyes big as gold coins.

Sophie kicked higher, flashing her bloomers and a pearly white smile. “I’m Whiskey Woo, the pirate queen! Whiskey Woo! Whiskey W—”

She saw the pirates’ faces and slowly stopped singing.

The pavilion went silent as a tomb.

Somewhere a parrot squawked.

“Blimey. That’s aworst shanty I ever ’eard,” Wesley spat.

“Bottom of the barrel,” said tattooed Thiago.

“Don’t deserve the word ‘barrel,’” said the fat pirate.

Agatha’s palms dripped. She could see Sophie flush-faced, knowing she’d just doomed them all—

Then like a sun ripping through clouds, the boys exploded into laughter.

“Might be pretty, but she’s stupid as a nut!” the handsome pirate howled.

“Don’t git too close or you might turn stupid too!” the runty one whooped. “Put that inna school handbook!”

“Feel sorry for ’er students! Their Dean’s a dope!” the fat one sniggered.

Sophie gaped at them, red as a beet.

“Get these clods to the Snake,” Wesley snarled, shaking his head. “Faster ye get ’em out of our sight, the faster we’re rid of ’em for good.”

“Whiskey Woo! Whiskey Woo!” his mates mocked.

Eager to deliver their bounties, the horsebound pirates whipped the kids on towards the castle. Agatha stared at Sophie, speechless.

“I saved us, didn’t I?” Sophie retorted.

As they filed out of the pavilion, they could hear pirates still jeering: “Whiskey Woo! Whiskey Woo!”

“A good laugh is worth its weight in gold!” Sophie called back at them angrily. “Better up that bounty on me now! A solid thousand, I’d say, wouldn’t you?”

“Whiskey Woo! Whiskey Woo!” the pirates ragged.

Nicola whispered to Agatha. “At least we have our noses.”

“She can’t outsmart the Snake by being a fool, Nicola!” Agatha hissed, straining against her cuffs. “Your shanty was right. Sophie can get him to take off his mask, but only if he likes her. How is she going to make him like her? With a limerick and a cha-cha?”

“Leave it to me. I’ll help her,” Nicola whispered.

“Yeah, right. You don’t know Sophie like I do—”

“This isn’t just your fairy tale anymore, Agatha,” Nicola said sharply.

Agatha was quiet.

“Listen,” said Nicola. “Ever since I got to the Woods, I’ve thought my real life was back in Gavaldon. But the Storian wrote all of us into this quest for a reason, including me. And the only way I’ll find out why I’m on this quest is if you let me be a part of it.” Her dark eyes softened. “Maybe you already have a best friend, Agatha. Maybe you don’t have room in your story for any more. But I have room in mine. Let me help you.”

Agatha searched the first year’s face. All this time, she thought she was the captain of this fairy tale. The only one who could steer them to a new happy ending, as if it were a mappable port on the shore. That’s another reason she’d left Tedros behind. Because in her toughest moments, Agatha trusted herself and herself alone.

And yet … maybe that’s why she could never find a happy ending that lasted.

She looked into Nicola’s eyes.

“Friends?” the first year asked.

“Friends,” said Agatha, a warm feeling spreading through her.

Together, the two girls raised their gaze to the castle, the chain pulling them towards its doors.

The warmth inside Agatha went cold.

A Snake was waiting.

TEDROS

Riddles and Mistrals

As Tedros swept through the White Tower, veering into dead ends and going round in circles, he kept passing the same square-jawed guard, smirking in his blue-and-gold uniform, daring him to ask for directions.

Tedros insisted to Lancelot he could meet the advisors without Lance taking him there. The knight demanded to come along, wary of a king treading into the dungeons on his own, but Tedros shoved past him, ordering him to stay behind. First of all, the advisors had made it clear they wanted to see him alone. Second, he didn’t want to admit he hadn’t a clue where the prison was after a lifetime of living in Camelot and six months of ruling it. And third, he was done passing the buck to others. On his first night in the castle, when the advisors had refused to see him, he’d let Lancelot throw them in jail instead of doing it himself.

But tonight he’d right that wrong. When it came to these advisors, this coming meeting felt personal.

He’d been roaming the White Tower for nearly an hour now, but the reddish torchlight made every hall look the same. Any time he opened a door it went wrong: a storage space filled with broken weapons … a steward undressing in his quarters … a laundry maid in the midst of ironing, so spooked at the sight of him she burnt through his shirt. … It was futile guesswork: the only part of White Tower that Tedros knew was the strange guest room his father had built on the second floor, which he kept returning to every few minutes like a rat restarting a maze.

Reaper could have shown me the way, Tedros thought, aware he was longing for a creature he’d often imagined falling into a lit fireplace. The cat seemed to know every nook and cranny of this castle. But after he’d kicked him in the guest room this morning, Reaper had vanished, no longer compelled to protect the king.

“Lost, Your Highness?” said the square-jawed guard as he passed.

“If I was, I’d ask,” said Tedros. “Especially since guards don’t speak to kings unless they’re spoken to first.”

The guard bolted to attention, spear to his chest.

One day these guards will look at me the way they looked at my father, Tedros thought, prowling through the empty staff dining room into a carpeted corridor. One day no one will question my place as king—

He tripped over a hole in a carpet and toppled through an open door, his crown flying off him, his body splaying onto a wet floor. He stood up gingerly, his chest and legs drenched. He lit his fingerglow and saw he was in a spacious bathroom, almost as big as his master bath in the Gold Tower. The floor was flooded an inch deep with water. Tedros scanned the bath with his glow until he found the source: a severed toilet hose that had dumped out the entire water tank. Tedros groaned and picked up his dripping crown, smushing it back on his head. He was about to trudge back into the hall and fetch one of the maids … but then something caught his eye.

Farther in, the bathroom had two side doors across from each other, each leading into opposing rooms. Which meant this bathroom was shared between whoever occupied those two rooms.

No wonder it’s so big, Tedros thought.

Curious as to why neither of the rooms’ inhabitants had noticed the leak, Tedros opened one of the side doors and stepped through—

He raised his brows.

It was the strange guest room, with the brown-and-orange rug, bare beige walls, and lonely bed in the corner. The one his father used to hide in during his drunken hazes.

But Tedros hadn’t used this door earlier today. He’d entered through the front door across the room, which still had his bloody handprint on it. And he’d used a key.

He turned and examined the door he’d just come in, with no doorknob on the inside and deftly concealed within the pattern of the wallpaper. It’s why he hadn’t seen it when he was in here this morning.

A secret door? To a guest room?

It didn’t make sense. Then again, many things in this castle didn’t make sense. Especially in the middle of the night, when he could feel his brain deadening and his eyes starting to close. But then another thought struck him—

Who shared the bathroom with this room?

He stepped through the secret door back into the bathroom and waded across the wet floor to the opposite side door.

He opened it—

A blast of perfume hit him, smelling of powdered rose. The small room had lavender wallpaper, a dark purple carpet, and a crisply made bed. A plate of half-eaten biscuits and an empty glass were on the nightstand, a dried-out lemon on the glass’s rim. Next to the glass was a leather-bound notebook. Tedros peeled it open and saw pages filled with Lady Gremlaine’s clear, graceful handwriting: schedules, to-do lists, addresses, notes to self. …

Tedros looked around the deserted room.

Shouldn’t she be sleeping?

There was nothing on the desk cabinets or mantel. He glanced back into the bathroom. There were no face creams or perfume bottles or even a toothbrush.

Tedros’ chest tingled.

He pulled the closet door. Empty. He yanked open the drawers and cabinets. Empty.

He rushed through the room’s main door into the hall and saw the square-jawed guard, reappeared.

Tedros frowned. “Weren’t you in the other … Never mind. Where’s Lady Gremlaine?”

The guard didn’t look at him, his narrow, hooded brown eyes fixed ahead. “Gone, Your Highness.”

“Yes, but gone where?”

“Packed up before lunch. Took all of her belongings and left the castle,” the guard said. “Said she was no longer needed.”

“What? Why would she—”

Tedros’ eyes widened. When they were in the Hall of Kings, he’d promised to stand up for her. To vouch for her after she’d helped him these past six months. He’d given Lady Gremlaine his word. But instead, he’d forgotten all about her and let his mother dismiss her, just like his dad once had.

“Like father, like son,” her words echoed.

Tedros hadn’t just been selfish. He’d been cruel.

The young king stiffened, heat coloring his cheeks.

It was time to swallow his pride.

Slowly he looked up at the guard.

“I seem to be lost after all,” Tedros said.

The dungeon wasn’t in the White Tower.

It was in the Gold Tower and to get there, they had to go through King’s Cove. Turns out Tedros had been working out right over the prison every morning and he hadn’t a clue. He followed the guard through the Gymnasium, tensing up as they passed Excalibur’s empty case, then tightening even more as the guard spotted King Arthur’s statue inside King’s Cove, the eyes gouged out.

“Your Highness,” he gasped, nostrils flaring, “someone has desecrated the—”

“I am aware, guard.”

“I’ll make sure to inform the other men—”

“I’m handling it,” Tedros clipped. “It’s one o’clock. I’d like to sleep tonight. Where is the prison?”

Still looking concerned, the guard stepped into the muggy grotto, the broad frame of his blue-and-gold uniform glowing in the pool’s ghostly light. The weak torches lit up the surface of the fungus-filled water and the slow, leaky cascade over the tall pile of rocks. The guard reached up to the statue of King Arthur holding Excalibur and twisted the sword’s hilt, the stone turning easily under his fingers.

All of a sudden the waterfall stopped running and the rocks parted, revealing a white stone door.

“I believe you have the key, Your Highness,” said the guard.

“Key?” said Tedros.

“Only you and Lady Gremlaine have keys to the door. Lady Gremlaine let us in each day to feed the prisoners. But if she didn’t leave her keys behind when she departed the castle, then only you can let us in now.”

Tedros took out his key ring. “But I don’t have the key to—”

He stopped. There was a coal-colored key scrunched between the many others on his ring—the one he always assumed opened a far-flung lockbox or weapons case. Skirting the edge of the pool, Tedros slipped through the gap in the rocks to reach the door and fit the black key into the lock. He pushed the door open, revealing a steep staircase down into darkness.

The guard lifted a torch off the wall and started descending the steps.

“This way, Your Highness.”

The young king followed quickly, trying not to breathe in the wet, fetid stench. Lancelot was right: the rest of the castle might be crumbling, but the real Royal Rot was hidden down beneath. Tedros was glad he hadn’t come alone.

“Has the prison always been here?” he asked the guard.

“Far as I know, Your Highness. Suppose the old kings enjoyed the thought of swimming idly while their prisoners festered below them. I’m not much older than you, so don’t take my word for it. Started my duties here only a few months after they packed you off to school.”

“How does one even become a guard at Camelot?” Tedros asked, guilty that he didn’t know the answer. In fact, he hadn’t ever remembered talking to a guard before. Growing up, he’d treated them like wallpaper.

“We go to school for it, Your Highness. Not all children get to attend the School for Good and Evil. Though I certainly wrote many a letter to the School Master, begging him to make me an Ever,” said the guard, starting to defrost.

“What kind of school did you go to?” Tedros prodded.

“An ordinary one, Your Highness. The Foxwood Boys School for Conservative Education,” the guard answered. “No magic or wizardry or fingerglows for us. No princess or king will ever ask our names. Storian won’t write ’em in a storybook. Unless we stumble into one. My mate from school almost got his name in The Tale of Sophie and Agatha—served breakfast at his inn to the League of Thirteen before the war against the School Master. But most of us go on to be blacksmiths and bricklayers, far away from any real adventure. I was a lucky one. Kingdoms come to the schools looking for the toughest boys for their royal guards. Had to undergo a whole lot of tests to prove my loyalty to Good. In the end, Camelot and Foxwood both wanted me. Foxwood’s home, but I couldn’t turn down a chance to serve King Arthur’s kingdom.”