полная версия

полная версияHarper's Young People, December 2, 1879

Watho called her Nycteris, and she grew as like Vesper as possible—in all but one particular. She had the same dark skin, dark eyelashes and brows, dark hair, and gentle, sad look; but she had just the eyes of Aurora, the mother of Photogen, and if they grew darker as she grew older, it was only a darker blue. Watho, with the help of Falca, took the greatest possible care of her—in every way consistent with her plans, that is, the main point in which was that she should never see any light but what came from the lamp. Hence her optic nerves, and indeed her whole apparatus for seeing, grew both larger and more sensitive; her eyes, indeed, stopped short only of being too large. She was a sadly dainty little creature. No one in the world except those two was aware of the being of the little bat. Watho trained her to sleep during the day, and wake during the night. She taught her music, and taught her scarcely anything else.

VI.—HOW PHOTOGEN GREW

The hollow in which the castle of Watho lay was a cleft in a plain rather than a valley among hills, for at the top of its steep sides, both north and south, was a table-land large and wide. It was covered with rich grass and flowers, with here and there a wood, the outlying colony of a great forest. These grassy plains were the finest hunting grounds in the world. The chief of Watho's huntsmen was a fine fellow, and when Photogen began to outgrow the training she could give him, she handed him over to Fargu. He with a will set about teaching him all he knew. He got him pony after pony, larger and larger as he grew, every one less manageable than that which had preceded it, and advanced him from pony to horse, and from horse to horse, until he was equal to anything in that kind which the country produced. In similar fashion he trained him to the use of bow and arrow substituting every three months a stronger bow and longer arrows, and soon he became, even on horseback, a wonderful archer. Every day, almost as soon as the sun was up, he went out hunting, and would in general be out nearly the whole of the day. But Watho had laid upon Fargu just one commandment, namely, that Photogen should on no account, whatever the plea, be out until sun-down, or so near it as to wake in him the desire of seeing what was going to happen; and this commandment Fargu was anxiously careful not to break; for although he would not have trembled had a whole herd of bulls come down upon him, charging at full speed across the level, and not an arrow left in his quiver, he was more than afraid of his mistress. So that, as Photogen grew older, Fargu began to tremble, for he found it steadily growing harder to restrain him. He did not know what fear was, and that not because he did not know danger; for he had had a severe laceration from the razor-like tusk of a boar—whose spine, however, he had severed with one blow of his hunting-knife before Fargu could reach him with defense.

When the boy was approaching his sixteenth year, Fargu ventured to beg of Watho that she would lay her commands upon the youth himself, and release him from responsibility for him. One might as soon hold a tawny-maned lion as Photogen, he said. Watho called the youth, laid her command upon him never to be out when the rim of the sun should touch the horizon, accompanying the prohibition with hints of consequences none the less awful that they were obscure. Photogen listened respectfully, but knowing neither the taste of fear nor the temptation of the night, her words were but sounds to him.

VII.—HOW NYCTERIS GREW

The little education she intended Nycteris to have, Watho gave her by word of mouth. Not meaning she should have light enough to read by, she never put a book in her hands. Nycteris, however, saw so much better than Watho imagined, that the light she gave her was quite sufficient, and she managed to coax Falca into teaching her the letters, after which she taught herself to read, and Falca now and then brought her a child's book. But her chief pleasure was in her instrument. Her very fingers loved it, and would wander about over its keys like feeding sheep. She was not unhappy. She knew nothing of the world except the tomb in which she dwelt, and had some pleasure in everything she did. But she desired, nevertheless, something more or different. She did not know what it was, and the nearest she could come to expressing it to herself was—that she wanted more room. Watho and Falca would go from her beyond the shine of the lamp, and come again; therefore surely there must be more room somewhere. As often as she was left alone she would fall to poring over the colored bas-reliefs on the walls. These were intended to represent various of the powers of Nature under allegorical similitudes, and as nothing can be made that does not belong to the general scheme, she could not fail at least to imagine a flicker of relationship between some of them, and thus a shadow of the reality of things found its way to her.

There was one thing, however, which moved and taught her more than all the rest—the lamp, namely, that hung from the ceiling, which she always saw alight, though she never saw the flame, only the slight condensation toward the centre of the alabaster globe. And besides the operation of the light itself after its kind, the indefiniteness of the globe, and the softness of the light, giving her the feeling as if her eyes could go in and into its whiteness, were somehow also associated with the idea of space and room. She would sit for an hour together gazing up at the lamp, and her heart would swell as she gazed. She would wonder what had hurt her when she found her face wet with tears, and then would wonder how she could have been hurt without knowing it. She never looked thus at the lamp except when she was alone.

[to be continued.]

WAITING FOR THEIR TURN.

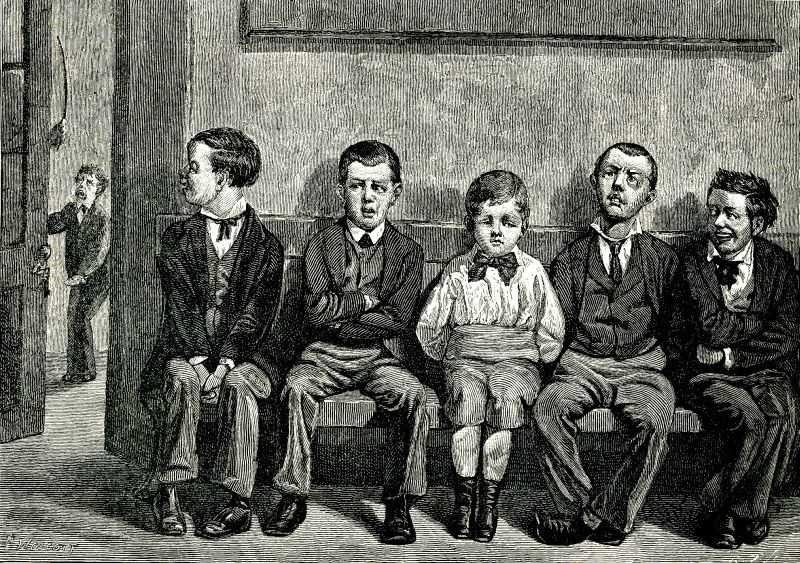

EMBROIDERED CANVAS RUG

Fig. 1.—Rug.—[See Figs. 2-4.]

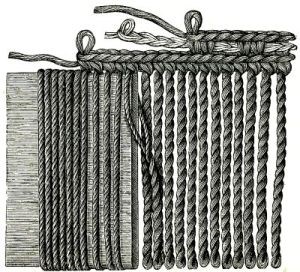

The pretty glove-case published in No. 2, November 11, was warmly welcomed, and our young friends are eagerly clamoring for more holiday gifts that they can make readily and cheaply. In compliance with their wish we will occasionally furnish fancy articles that can be manufactured by little hands. One of the most tasteful and useful presents that we can suggest is a handsome canvas rug, which can be easily made with the help of the accompanying pictures and description, and which is sure to prove a successful Christmas gift. The rug is made of écru linen Java canvas, which, with the border, can be bought cheaply in any large fancy store. The centre of the rug is twenty-eight inches long and nineteen inches wide, and is embroidered in loop stitch with claret-colored worsted. The border is four inches wide, and is worked in cross stitch with similar worsted. That useful periodical, Harper's Bazar, gives full directions for working these and many other stitches. Almost every little girl, however, knows how to make these simple stitches, or can find some one to show her. The rug is lined with gray drilling, and edged with fringe, of which the illustration Fig. 4 shows a full-sized section.

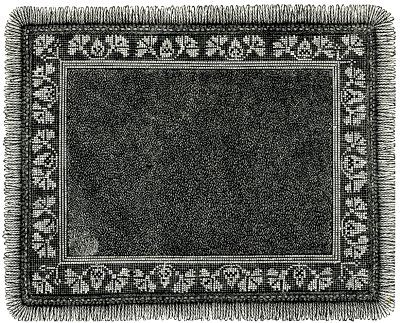

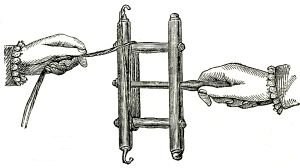

Fig. 2.—Reel for Rug, Fig. 1.

Fig. 3.—Reel for Rug, Fig. 1.

To make the fringe first twist together threads of claret-colored worsted. For this purpose use a wooden reel, the middle rod of which forms a movable handle. One side of the reel is furnished with brass hooks on the ends. Lay a thread of claret-colored worsted on the upper hook as shown by Fig. 2; turn the reel quickly, holding the thread double with the left hand and the handle of the reel with the right hand until the thread has been twisted long enough to be wound on the reel, with the hands in the position as shown by Fig. 3. When the threads have been twisted of sufficient length, wind them tight on a long wooden board four inches and seven-eighths in circumference (see Fig. 4), and for the heading of the fringe crochet on each thread 1 sc. (single crochet) with claret-colored worsted. Withdraw the board from the loops, twist these, and on the sc. work a second round of sc. with similar worsted, at the same time fastening in a chain stitch foundation worked with écru cotton. In doing this, work alternately 2 sc. on the foundation and 2 sc. without the foundation.

Fig. 4.—Manner of making Fringe for Rug, Fig. 1.

Another simple fringe is made by winding the worsted on a suitable-sized book, then cutting it through on one end, and knotting strands of four threads each into the edge of the rug.

Electric Ornaments.—Some curious trinkets, to which certain motions can be given at will by means of electricity, have recently been devised by an ingenious Frenchman, M. Trouvé. Two of these are scarf pins; one has a death's-head, gold or enamel, with diamond eyes and lower articulated jaw; the other has a rabbit seated upright on a box with a little bell before it, to be struck with two rods held in the animal's fore-paws. An invisible wire connects these objects with a small hermetically closed battery, the ebonite case of which is about the size of a cigarette. It is kept in the waistcoat pocket, and acts only when turned horizontally or inverted. When a person looks at the pin, the owner, slipping a finger into his pocket, moves the battery, whereupon the death's-head rolls its eyes and grinds its teeth, or the little rabbit beats the bell with its rods (through electro-magnetic action). A third kind of ornament is a small bird set with diamonds, to be fixed in a lady's hair, and the wings of which can be set in motion electrically.

The Great Wall of China.—An American engineer engaged in the construction of a railway in China, gives the following account of this wonderful work. The wall is 1728 miles long, 18 feet high, and 15 feet thick at the top. The foundation throughout is of solid granite, the remainder of compact masonry. At intervals of between two hundred and three hundred yards towers rise up, twenty-five to thirty feet high, and twenty-four feet in diameter. On the top of the wall and on both sides of it are masonry parapets to enable the defenders to pass unseen from one tower to another. The wall is carried from point to point in a straight line, across valleys, plains, and hills, sometimes plunging down into deep abysses. Rivers are bridged over by the wall, while on both banks of large streams strong flanking towers are placed.

MARGOTTE'S STORY

"I will tell you the story," said Margotte, pausing in her knitting, as we leaned together over the white palings of her little garden. "Yes, there is a story, madame—a story of a wolf; but you have got it wrong, madame, and I must set you right."

Picture a sunset in the Pyrenees, a glorious crimson sky tipping the distant peaks with pale pink, and deepening the purple shadows on the nearer mountains—the mountains that inclose and overtop Margotte Nevaire's pretty home. I had come for a quiet month to this picturesque, secluded village, and though my month was over, I was tempted to linger day after day, for the sake of the sunshine and the mountains, and not least, perhaps, for the sake of these two peasant girls, with whom I lodged.

Margotte was the youngest of the two by fifteen years—the three boys who came between had died—and though it is very long since we leaned side by side over the white palings, I can always call her to mind as she stood knitting there.

She was tall and strong, and finely made, with a clear white skin, and brown hair waving in heavy masses under her white starched caps. She had beautiful eyes, heavy-lidded and dark-lashed, and a firm, sweet mouth—such a woman as you see sometimes amongst the desolate mountains, as if God had given to them a grander soul, to compensate for the blessings He denied.

Léontine was different; tall too, and active, but with heavier movements, and more of firmness than of sweetness in her scarred face. She had no girlish vanity in her glossy hair, or the cap starched to such absolute perfection, for so much of her youth and beauty had vanished with that scar—a deep blue line from brow to chin—that no loving arrangement of the hair by Margotte's deft fingers could hide.

So Margotte said to me that evening, dropping her knitting into her apron pocket: "I will tell you the story of the wolf, madame. Léontine is out, and it is a grand story—a story I should like you to hear."

"It was night," said Margotte, "a cruel, cold winter night, such as we who live amongst the mountains have terrible cause to dread, for it means hunger and cold—sometimes absolute famine. It means the children crying for food when there is none to give them, and the wolves howling in the distance. Ah! those wolves, madame, how they make one shudder with their monotonous howls, that seem so near at first, and then die away into the far distance!

"Well, it was night, as I have said, and the baby was asleep, as it might be here, and Léontine was knitting on the hearth, and Marcelle, a friend of Léontine's, was chattering to her, kneeling on the stones, and the door was on the latch.

"That was the mischief, you see; but Léontine was young then, and Marcelle was a giddy, thoughtless chatterer, and she had run in with her shawl over her head for an hour's talk. Léontine has told me of it so often that I almost seem to see the two girls crouching by the fire that sent bright and flickering reflections on to the snow outside.

"Suddenly, as they talked, there came distinctly to them the howling of the wolves across the snow. Marcelle put her hands over her ears and shuddered. Léontine knelt up and stirred the fire.

"'Come closer, my friend,' she said; 'it is a dreary sound. Thank God, we are safe here!'

"'Are we safe, do you think?' asked Marcelle, with chattering teeth. 'I dare not go home to-night. Will your mother let me stay here, Léontine?'

"'Surely,' said Leontine.

"She was so brave, my sister, my dear, dear sister, madame, and so gentle! she took Marcelle's head upon her knee, and put her knitting aside to soothe her terror.

"'We are quite safe, Marcelle,' she said, 'and mother will soon be back. It is a dreary night.'

"It was a dreary night, dark and still and terribly cold; the white flakes were falling slowly to the earth, and covering the mother's footsteps on the path.

"Léontine walked over to the window and looked out; the fire-light was dancing and flickering on the snow outside, and making a cheerful patch of ruddy light in the darkness, which would guide the mother's steps for her home-coming. Through the darkness the howling of the wolves seemed nearer.

"'Ah, they are coming closer,' said Marcelle, starting upright. 'Can you see them, Léontine? I am afraid.'

"Léontine was leaning close to the glass, pressing her face against it.

"'Yes, I see shadows,' she said; 'they are coming to the light, Marcelle. No! it is only one shadow, after all; we must not frighten each other.'

"She turned with a faint smile to Marcelle's shuddering face, and tried to draw the curtains with her trembling hands, but the shadow on the snow was very near.

"'Do not be afraid, my dear,' she said, kneeling down upon the hearth again, and drawing Marcelle's cold hands into her own strong ones; 'be brave; we are quite safe, you know; the door is strong, and God is so good, Marcelle.'

"But Marcelle was sobbing.

"Her sobbing woke the baby, and it cried—little moaning cries that fretted Léontine, and that brought the dark shadow nearer to the door.

"Léontine rocked the baby, but could not hush its wailing cries; she knelt beside the cradle, singing her strange, weird songs in a voice that never trembled, and all the time that foolish Marcelle was sobbing and trembling at her feet.

"'Hush, for God's sake!' said Léontine at last, lifting her clear eyes, and trying to still the faltering of her voice. 'You frighten me, Marcelle, and you keep baby fretful. Mother will soon be home, and the night is not long, and we are quite safe, thank God.'

"But the words were still in her mouth when she heard a heavy shuffling in the snow outside, and a terrible howl that seemed to shake the little cottage to its foundations. Then—ah! think of it, madame—the door—this door against which you lean—was burst open, and out of the darkness a great wolf came bounding in, and paused for a minute on the threshold.

"Léontine was upright in an instant, standing before the cradle. Even Marcelle rose also, and stood shrieking on the hearth.

"But the great, lean, hungry wolf came slinking on—and it passed Léontine, and took the little baby from the cradle.

"Léontine had stood as if rooted to the spot, with her burning eyes fascinated by the awful sight; but now she strode to the table, and took a knife. And yet she dared not throw it, because of the baby, madame.

"They seemed so helpless all of a sudden, those two girls, while the great beast crept past them again, trotting to the door. Marcelle had taken a fagot from the fire, and cast it at him, but he only shook it off, and growled savagely, bounding out into the snow.

"Ah, madame, it was terrible—terrible; and yet, as Léontine always says, God is good.

"For while Marcelle was crying by the empty cradle, and the snow was sweeping into the room and putting out the fire, Léontine had sprung to the door, and had flung herself to the ground, with her brave white face not two inches from the wolf's glaring eyes; she stretched out her hands and caught him by his shaggy coat, twisting her strong fingers into his matted hair. She still held her knife firmly, but she dared not use it.

"She succeeded in her wish, madame, however; the wolf was surprised and angry. With a low, fierce growl, that made Marcelle's heart beat to suffocation, he dropped the baby.

"Léontine has told me often that she never knows how she came living out of that terrible struggle; she says she remembers crying aloud to God to keep the baby safe, and to take the life she offered up so willingly instead. She remembers striking with her knife at the great body that fell upon her, blinding and suffocating her; then there came to her ears a dim faint sound like music, and my cries—I was the baby, you have guessed, madame—and then silence, such silence as Léontine says she thinks will be like the silence of death.

"But it was not death. Ah, no—there is Léontine, you see, coming up with her pitcher from the well; and the wolf, the last wolf killed in St. Privât, lies buried not a foot from where we stand; but Léontine will carry her trophy of victory to her dying day. Some people say that her face would be very beautiful but for the scar; but for me, madame, I think that it is the scar that makes her face so beautiful."

Our young friends must not be impatient if their communications are not noticed immediately. Our space is limited, and we answer or print letters in the order in which they are received. The following pleasant note comes from a young correspondent in Paterson:

Dear "Young People,"—If all the boys and girls were as glad to see you as I was, you must have received a very flattering welcome. We have felt the want of a cheap, first-class weekly paper so much that we are able to appreciate you now that we have you. There are several weeklies published for the "young," but the great objection to them is that half are too dry, and the other half too sensational. You are neither, but very interesting.

In answer to a question accompanying the above note, we would say that there is no limit to the age of our contributors.

George S. Vail.—We will accept original puzzles if they are very good. They must, in all cases, be accompanied by a full solution. Your chicken story is very pretty, but we have no room to print it.

Chester B. Fernald.—The full operation in figures should be sent with all answers to mathematical puzzles.

Lyman C.—Your land-turtle will eat pieces of pear or sweet apple, bread, cake, and many other things. It will also live many months without eating at all. You can keep it in a box, and it will be happier if you give it a little earth to dig in. If the earth is deep enough, it will make a burrow and sleep in it until next spring. We knew a little girl who received a present of two land-turtles, which she placed in the yard. In a few days she was unable to find them, and gave them up for lost. The next spring, six months afterward, she was digging in her flower beds, when, to her astonishment, she found her two lost pets, who opened their eyes on being disturbed, and crawled sluggishly out of their hole. They had been asleep all through the cold weather, for turtles are very long lived, and they can easily give a whole winter to a single nap. Rev. Mr. Wood, in a note to White's Natural History of Selborne, gives a very interesting account of a tame turtle which he allowed to crawl about his study. This turtle showed a great genius for climbing, and at one time actually succeeded in scrambling upon a footstool. He says: "Its food consisted of bread and milk, which it ate several times a day, drinking the milk by scooping up some of it in its lower jaw, and then by throwing its head back the milk ran down its throat."

Young Chemist.—Spread on your paper first a solution of iodide of potassium, then a solution of nitrate of silver. Iodide of silver forms, and saturates the paper. The excess of nitrate of silver and the heavy yellow powder which forms are now washed off, and the paper is ready for the camera. The picture may be developed by a solution of gallic acid mixed with a very small quantity of an aqueous solution of acetic acid and nitrate of silver. The picture is fixed by washing with hyposulphite of soda. If you wish to derive any pleasure from photography, you would better drop the old-fashioned paper process, and turn your attention to ferrotypes, or negatives on glass, as with them good results are more easily obtained than with paper.

We acknowledge very pretty and neatly written letters from St. Clair Nichol, Listowel, Ontario, and Charles L. Benjamin (nine years old), Washington, D. C., both containing correct information respecting Sir Rowland Hill.

Clarissa H. H.—Your answer to No. 4 of the mathematical puzzles is right. If you look carefully you will discover why the others are wrong.

G. A. Page sends correct answers to Nos. 1, 3, and 4 of the mathematical puzzles in our second number; also to numerical charade. Many thanks to "an instructor and lover of young people" for her kind note. We are sorry it is anonymous.

A correspondent sends answers to puzzles which we have not considered, as no signature accompanies them. Our young friends will please sign their full names to communications, which we will not print if so requested.

Harper's Young People

Harper's Young People will be issued every Tuesday, and may be had at the following rates:

Four cents a number.

Single subscriptions for one year, $1.50; five subscriptions, one year, $7.00: payable in advance. Postage free.

Subscriptions may begin with any number. When no time is specified, it will be understood that the subscriber desires to commence with the number issued after the receipt of order.

Remittances should be made by Post-office Money Order, or Draft, to avoid risk of loss.

Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York.

A LIBERAL OFFER FOR 1880 ONLY

☞ Harper's Young People and Harper's Weekly will be sent to any address for one year, commencing with the first number of Harper's Weekly for January, 1880, on receipt of $5.00 for the two Periodicals.