полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

Of the Carolina's crew of 70 men, five were British. This fact was not found out till three deserted, when an investigation was made and the two other British discharged. Captain Henly, in reporting these facts, made no concealment of his surprise that there should be any British at all in his crew. [Footnote: See his letter in "Letters of Masters' Commandant," 1814, I. No. 116.]

From these facts and citations we may accordingly conclude that the proportion of British seamen serving on American ships after the war broke out, varied between none, as on the Wasp and Constitution, to ten per cent., as on the Chesapeake and Essex. On the average, nine tenths of each of our crews were American seamen, and about one twentieth British, the remainder being a mixture of various nationalities.

On the other hand, it is to be said that the British frigate Guerrière had ten Americans among her crew, who were permitted to go below during action, and the Macedonian eight, who were not allowed that privilege, three of them being killed. Three of the British sloop Peacock's men were Americans, who were forced to fight against the Hornet: one of them was killed. Two of the Epervier's men were Americans, who were also forced to fight. When the crew of the Nautilus was exchanged, a number of other American prisoners were sent with them; among these were a number of American seamen who had been serving in the Shannon, Acasta, Africa, and various other vessels. So there was also a certain proportion of Americans among the British crews, although forming a smaller percentage of them than the British did on board the American ships. In neither case was the number sufficient to at all affect the result.

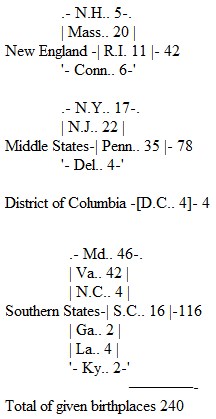

The crews of our ships being thus mainly native Americans, it may be interesting to try to find out the proportions that were furnished by the different sections of the country. There is not much difficulty about the officers. The captains, masters commandant, lieutenants, marine officers, whose birthplaces are given in the Navy List of 1816,—240 in all,—came from the various States as follows:

Thus, Maryland furnished, both absolutely and proportionately, the greatest number of officers, Virginia, then the most populous of all the States, coming next; four fifths of the remainder came from the Northern States.

It is more difficult to get at the birthplaces of the sailors. Something can be inferred from the number of privateers and letters of marque fitted out. Here Baltimore again headed the list; following closely came New York, Philadelphia, and the New England coast towns, with, alone among the Southern ports, Charleston, S.C. A more accurate idea of the quotas of sailors furnished by the different sections can be arrived at by comparing the total amount of tonnage the country possessed at the outbreak of the war. Speaking roughly, 44 per cent, of it belonged to New England, 32 per cent, to the Middle States, and 11 per cent, to Maryland. This makes it probable (but of course not certain) that three fourths of the common sailors hailed from the Northern States, half the remainder from Maryland, and the rest chiefly from Virginia and South Carolina.

Having thus discussed somewhat at length the character of our officers and crews, it will now be necessary to present some statistical tables to give a more accurate idea of the composition of the navy; the tonnage, complements, and armaments of the ships, etc.

At the beginning of the war the Government possessed six navy-yards (all but the last established in 1801) as follows: [Footnote: Report of Naval Secretary Jones, Nov. 30. 1814.]

Place Original Cost. Minimum number of men employed.

1. Portsmouth. N. H., $ 5,500 10

2. Charleston, Mass., 39,214 20

3. New York, 40,000 102

4. Philadelphia, 37,000 13

5. Washington, 4,000 36

6. Gosport, 12,000 16

In 1812 the following was the number of officers in the navy: [Footnote: "List of Vessels" etc., by Gen. H Preble U.S.N (1874)]

12 captains

10 masters commandant

73 lieutenants

53 masters

310 midshipmen

42 marine officers

––

500

At the opening of the year, the number of seamen, ordinary seamen, and boys in service was 4,010, and enough more were recruited to increase it to 5,230, of whom only 2,346 were destined for the cruising war vessels, the remainder being detailed for forts, gun-boats, navy yards, the lakes, etc. [Footnote: Report of Secretary Paul Hamilton, Feb. 21, 1812.] The marine corps was already ample, consisting of 1,523 men. [Footnote: Ibid.]

No regular navy lists were published till 1816, and I have been able to get very little information respecting the increase in officers and men during 1813 and 1814; but we have full returns for 1815, which may be summarized as follows: [Footnote: Seybert's "Statistical Annals," p. 676 (Philadelphia, 1818)]

30 captains,

25 masters commandant,

141 lieutenants,

24 commanders,

510 midshipmen,

230 sailing-masters,

50 surgeons,

12 chaplains,

50 pursers,

10 coast pilots,

45 captain's clerks,

80 surgeon's mates,

530 boatswains, gunners, carpenters, and sailmakers,

268 boatswain's mates, gunner's mates, etc.,

1,106 quarter gunners, etc.,

5,000 able seamen,

6,849 ordinary seamen and boys.

Making a total of 14,960, with 2,715 marines.

[Footnote: Report of Secretary B. W. Crowninshield, April 18, 1816.]

Comparing this list with the figures given before, it can be seen that during the course of the war our navy grew enormously, increasing to between three and four times its original size.

At the beginning of the year 1812, the navy of the United States on the ocean consisted of the following vessels, which either were, or could have been, made available during the war. [Footnote: Letter of Secretary Benjamin Stoddart to Fifth Congress, Dec. 24, 1798; Letter of Secretary Paul Hamilton, Feb. 21, 1812; "American State Papers," vol. xix, p. 149. See also The "History of the Navy of the United States," by Lieut. G. E. Emmons, U. S. N. (published in Washington, MDCCCLIII, under the authority of the Navy Department.)]

Rate When

(Guns). Name. Where Built. Built. Tonnage. Cost.

44 United States, Philadelphia, 1797 1576 $299,336

44 Constitution, Boston, 1797 1576 302,718

44 President, New York, 1800 1576 220,910

38 Constellation, Baltimore, 1797 1265 314,212

38 Congress, Portsmouth, 1799 1268 197,246

38 Chesapeake, Norfolk, 1799 1244 220,677

32 Essex, Salem, 1799 860 139,362

28 Adams, New York, 1799 560 76,622

18 Hornet, Baltimore, 1805 480 52,603

18 Wasp, Washington, 1806 450 40,000

16 Argus, Boston, 1803 298 37,428

16 Syren, Philadelphia, 1803 250 32,521

14 Nautilus, Baltimore, 1803 185 18,763

14 Vixen, Baltimore, 1803 185 20,872

12 Enterprise, Baltimore, 1799 165 16,240

12 Viper, Purchased, 1810 148

There also appeared on the lists the New York, 36, Boston, 28, and John Adams, 28. The two former were condemned hulks; the latter was entirely rebuilt after the war. The Hornet was originally a brig of 440 tons, and 18 guns; having been transformed into a ship, she was pierced for 20 guns, and in size was of an intermediate grade between the Wasp and the heavy sloops, built somewhat later, of 509 tons. Her armament consisted of 32-pound carronades, with the exception of the two bow-guns, which were long 12's. The whole broadside was in nominal weight just 300 pounds; in actual weight about 277 pounds. Her complement of men was 140, but during the war she generally left port with 150. [Footnote: In the Hornet's log of Oct. 25, 1812, while in port, it is mentioned that she had 158 men; four men who were sick were left behind before she started. (See, in the Navy Archives, the Log-book, Hornet, Wasp, and Argus, July 20, 1809, to Oct. 6, 1813.)] The Wasp had been a ship from the beginning, mounted the number of guns she rated (of the same calibres as the Hornet's) and carried some ten men less. She was about the same length as the British 18-gun brig-sloop, but, being narrower, measured nearly 30 tons less. The Argus and Syren were similar and very fine brigs, the former being the longer. Each carried two more guns than she rated; and the Argus, in addition, had a couple thrust through the bridle-ports. The guns were 24-pound carronades, with two long 12's for bow-chasers. The proper complement of men was 100, but each sailed usually with about 125. The four smaller craft were originally schooners, armed with the same number of light long guns as they rated, and carrying some 70 men apiece; but they had been very effectually ruined by being changed into brigs, with crews increased to a hundred men. Each was armed with 18-pound carronades, carrying two more than she rated. The Enterprise, in fact, mounted 16 guns, having two long nines thrust through the bridle-ports. These little brigs were slow, not very seaworthy, and overcrowded with men and guns; they all fell into the enemy's hands without doing any good whatever, with the single exception of the Enterprise, which escaped capture by sheer good luck, and in her only battle happened to be pitted against one of the corresponding and equally bad class of British gun-brigs. The Adams after several changes of form finally became a flush-decked corvette. The Essex had originally mounted twenty-six long 12's on her main-deck, and sixteen 24-pound carronades on her spar-deck; but official wisdom changed this, giving her 46 guns, twenty-four 32-pound carronades, and two long 12's on the main-deck, and sixteen 32-pound carronades with four long 12's on the spar-deck. When Captain Porter had command of her he was deeply sensible of the disadvantages of an armament which put him at the mercy of any ordinary antagonist who could choose his distance; accordingly he petitioned several times, but always without success, to have his long 12's returned to him.

The American 38's were about the size of the British frigates of the same rate, and armed almost exactly in the same way, each having 28 long 18's on the main-deck and 20 32-pound carronades on the spar-deck. The proper complement was 300 men, but each carried from 30 to 80 more. [Footnote: The Chesapeake, by some curious mistake, was frequently rated as a 44, and this drew in its train a number of attendant errors. When she was captured, James says that in one of her lockers was found a letter, dated in February, 1811, from Robert Smith, the Secretary of War, to Captain Evans, at Boston, directing him to open houses of rendezvous for manning the Chesapeake, and enumerating her crew at a total of 443. Naturally this gave British historians the idea that such was the ordinary complement of our 38-gun frigates. But the ordering so large a crew was merely a mistake, as may be seen by a letter from Captain Bainbridge to the Secretary of the Navy, which is given in full in the "Captains' Letters," vol. xxv. No. 19 (Navy Archives). In it he mentions the extraordinary number of men ordered for the Chesapeake, saying, "There is a mistake in the crew ordered for the Chesapeake, as it equals in number the crews of our 44-gun frigates, whereas the Chesapeake is of the class of the Congress and Constellation."]

Our three 44-gun ships were the finest frigates then afloat (although the British possessed some as heavy, such as the Egyptienne, 44). They were beautifully modelled, with very thick scantling, extremely stout masts, and heavy cannon. Each carried on her main-deck thirty long 24's, and on her spar-deck two long bow-chasers, and twenty or twenty-two carronades—42-pounders on the President and United States, 32-pounders on the Constitution. Each sailed with a crew of about 450 men—50 in excess of the regular complement. [Footnote: The President when in action with the Endymion had 450 men aboard, as sworn by Decatur; the muster-roll of the Constitution, a few days before her action with the Guerrière contains 464 names (including 51 marines); 8 men were absent in a prize, so she had aboard in the action 456. Her muster-roll just before the action with the Cyane and Levant shows 461 names.]

It may be as well to mention here the only other class of vessels that we employed during the war. This was composed of the ship-sloops built in 1813, which got to sea in 1814. They were very fine vessels, measuring 509 tons apiece, [Footnote: The dimensions were 117 feet 11 inches upon the gun-deck, 97 feet 6 inches keel for tonnage, measuring from one foot before the forward perpendicular and along the base line to the front of the rabbet of the port, deducting 3/5 of the moulded breadth of the beam, which is 31 feet 6 inches; making 509 21/95 tons. (See in Navy Archives, "Contracts," vol. ii. p. 137.)] with very thick scantling and stout masts and spars. Each carried twenty 32-pound carronades and two long 12's with a crew nominally of 160 men, but with usually a few supernumeraries. [Footnote: The Peacock had 166 men, as we learn from her commander Warrington's letter of June 1st (Letter No. 140 in "Masters' Commandant Letters," 1814, vol. i). The Frolic took aboard "10 or 12 men beyond her regular complement" (see letter of Joseph Bainbridge, No. 51, in same vol.). Accordingly when she was captured by the Orpheus, the commander of the latter, Captain Hugh Pigot, reported the number of men aboard to be 171. The Wasp left port with 173 men, with which she fought her first action; she had a much smaller number aboard in her second.]

The British vessels encountered were similar, but generally inferior, to our own. The only 24-pounder frigate we encountered was the Endymion of about a fifth less force than the President. Their 38-gun frigates were almost exactly like ours, but with fewer men in crew as a rule. They were three times matched against our 44-gun frigates, to which they were inferior about as three is to four. Their 36-gun frigates were larger than the Essex, with a more numerous crew, but the same number of guns; carrying on the lower deck, however, long 18's instead of 32-pound carronades,—a much more effective armament. The 32-gun frigates were smaller, with long 12's on the main-deck. The largest sloops were also frigate-built, carrying twenty-two 32-pound carronades on the main-deck, and twelve lighter guns on the quarter-deck and forecastle, with a crew of 180. The large flush-decked ship-sloops carried 21 or 23 guns, with a crew of 140 men. But our vessels most often came in contact with the British 18-gun brig-sloop; this was a tubby craft, heavier than any of our brigs, being about the size of the Hornet. The crew consisted of from 110 to 135 men; ordinarily each was armed with sixteen 32-pound carronades, two long 6's, and a shifting 12-pound carronade; often with a light long gun as a stern-chaser, making 20 in all. The Reindeer and Peacock had only 24-pound carronades; the Epervier had but eighteen guns, all carronades. [Footnote: The Epervier was taken into our service under the same name and rate. Both Preble and Emmons describe her as of 477 tons. Warrington, her captor, however, says: "The surveyor of the port has just measured the Epervier and reports her 467 tons." (In the Navy Archives, "Masters' Commandant Letters," 1814, i. No. 125.) For a full discussion of tonnage, see Appendix, A.]

Among the stock accusations against our navy of 1812, were, and are, statements that our vessels were rated at less than their real force, and in particular that our large frigates were "disguised line-of-battle ships." As regards the ratings, most vessels of that time carried more guns than they rated; the disparity was less in the French than in either the British or American navies. Our 38-gun frigates carried 48 guns, the exact number the British 38's possessed. The worst case of underrating in our navy was the Essex, which rated 32, and carried 46 guns, so that her real was 44 per cent, in excess of her nominal force; but this was not as bad as the British sloop Cyane, which was rated a 20 or 22, and carried 34 guns, so that she had either 55 or 70 per cent, greater real than nominal force. At the beginning of the war we owned two 18-gun ship-sloops, one mounting 18 and the other 20 guns; the 18-gun brig-sloops they captured mounted each 19 guns, so the average was the same. Later we built sloops that rated 18 and mounted 22 guns, but when one was captured it was also put down in the British navy list as an 18-gun ship-sloop. During all the combats of the war there were but four vessels that carried as few guns as they rated. Two were British, the Epervier and Levant, and two American, the Wasp and Adams. One navy was certainly as deceptive as another, as far as underrating went.

The force of the statement that our large frigates were disguised line-of-battle ships, of course depends entirely upon what the words "frigate" and "line-of-battle ship" mean. When on the 10th of August, 1653, De Ruyter saved a great convoy by beating off Sir George Ayscough's fleet of 38 sail, the largest of the Dutch admiral's "33 sail of the line" carried but 30 guns and 150 men, and his own flag-ship but 28 guns and 134 men. [Footnote: La Vie et les Actions Memorables du Sr. Michel de Ruyter, à Amsterdam, Chez Henry et Theodore Boom. MDCLXXVII. The work is by Barthelemy Pielat, a surgeon in de Ruyter's fleet, and personally present during many of his battles. It is written in French, but is in tone more strongly anti-French than anti-English.] The Dutch book from which this statement is taken speaks indifferently of frigates of 18, 40, and 58 guns. Toward the end of the eighteenth century the terms had crystallized. Frigate then meant a so-called single-decked ship; it in reality possessed two decks, the main- or gun-deck, and the upper one, which had no name at all, until our sailors christened it spar-deck. The gun-deck possessed a complete battery, and the spar-deck an interrupted one, mounting guns on the forecastle and quarter-deck. At that time all "two-decked" or "three-decked" (in reality three- and four-decked) ships were liners. But in 1812 this had changed somewhat; as the various nations built more and more powerful vessels, the lower rates of the different divisions were dropped. Thus the British ship Cyane, captured by the Constitution, was in reality a small frigate, with a main-deck battery of 22 guns, and 12 guns on the spar-deck; a few years before she would have been called a 24-gun frigate, but she then ranked merely as a 22-gun sloop. Similarly the 50- and 64-gun ships that had fought in the line at the Doggerbank, Camperdown, and even at Aboukir, were now no longer deemed fit for the purpose, and the 74 was the lowest line-of-battle ship.

The Constitution, President, and States must then be compared with the existing European vessels that were classed as frigates. The French in 1812 had no 24-pounder frigates, for the very good reason that they had all fallen victims to the English 18-pounder's; but in July of that year a Danish frigate, the Nayaden, which carried long 24's, was destroyed by the English ship Dictator, 64.

The British frigates were of several rates. The lowest rated 32, carrying in all 40 guns, 26 long 12's on the main-deck and 14 24-pound carronades on the spar-deck—a broadside of 324 pounds. [Footnote: In all these vessels there were generally two long 6's or 9's substituted for the bow-chase carronades.] The 36-gun frigates, like the Phoebe, carried 46 guns, 26 long 18's on the gun-deck and 32-pound carronades above. The 38-gun frigates, like the Macedonian, carried 48 or 49 guns, long 18's below and 32-pound carronades above. The 32-gun frigates, then, presented in broadside 13 long 12's below and 7 24-pound carronades above; the 38-gun frigates, 14 long 18's below and 10 32-pound carronades above; so that a 44-gun frigate would naturally present 15 long 24's and 12 42-pound carronades above, as the United States did at first. The rate was perfectly proper, for French, British, and Danes already possessed 24-pounder frigates; and there was really less disparity between the force and rate of a 44 that carried 54 guns than there was in a 38 that carried 49, or, like the Shannon, 52. Nor was this all. Two of our three victories were won by the Constitution, which only carried 32-pound carronades, and once 54 and once 52 guns; and as two thirds of the work was thus done by this vessel, I shall now compare her with the largest British frigates. Her broadside force consisted of 15 long 24's on the main-deck, and on the spar-deck one long 24, and in one case 10, in the other 11 32-pound carronades—a broadside of 704 or 736 pounds. [Footnote: Nominally; in reality about 7 per cent, less on account of the short weight in the metal.] There was then in the British navy the Acasta, 40, carrying in broadside 15 long 18's and 11 32-pound carronades; when the spar-deck batteries are equal, the addition of 90 pounds to the main-deck broadside (which is all the superiority of the Constitution over the Acasta) is certainly not enough to make the distinction between a frigate and a disguised 74. But not considering the Acasta, there were in the British navy three 24-pounder frigates, the Cornwallis, Indefatigable, and Endymion. We only came in contact with the latter in 1815, when the Constitution had but 52 guns. The Endymion then had an armament of 28 long 24's, 2 long 18's, and 20 32-pound carronades, making a broadside of 674 pounds, [Footnote: According to James 664 pounds; he omits the chase guns for no reason.] or including a shifting 24-pound carronade, of 698 pounds—just six pounds, or 1 per cent, less than the force of that "disguised line-of-battle ship" the Constitution! As the Endymion only rated as a 40, and the Constitution as a 44, it was in reality the former and not the latter which was underrated. I have taken the Constitution, because the British had more to do with her than they did with our other two 44's taken together. The latter were both of heavier metal than the Constitution, carrying 42-pound carronades. In 1812 the United States carried her full 54 guns, throwing a broadside of 846 pounds; when captured, the President carried 53, having substituted a 24-pound carronade for two of her 42's, and her broadside amounted to 828 pounds, or 16 per cent nominal, and, on account of the short weight of her shot, 9 per cent, real excess over the Endymion. If this difference made her a line-of-battle ship, then the Endymion was doubly a line-of-battle ship compared to the Congress or Constellation. Moreover, the American commanders found their 42-pound carronades too heavy; as I have said the Constitution only mounted 32's, and the United States landed 6 of her guns. When, in 1813, she attempted to break the blockade, she carried but 48 guns, throwing a broadside of 720 pounds—just 3 per cent more than the Endymion. [Footnote: It was on account of this difference of 3 per cent that Captain Hardy refused to allow the Endymion to meet the States (James, vi. p. 470). This was during the course of some challenges and counter-challenges which ended in nothing, Decatur in his turn being unwilling to have the Macedonian meet the Statira, unless the latter should agree not to take on a picked crew. He was perfectly right in this; but he ought never to have sent the challenge at all, as two ships but an hour or two out of port would be at a frightful disadvantage in a fight.] If our frigates were line-of-battle ships the disguise was certainly marvellously complete, and they had a number of companions equally disguised in the British ranks.