полная версия

полная версияThe Naval War of 1812

Meanwhile Colonel Thornton's attack on the opposite side had been successful, but had been delayed beyond the originally intended hour. The sides of the canal by which the boats were to be brought through to the Mississippi caved in, and choked the passage, [Footnote: Codrington, i, 386.] so that only enough got through to take over a half of Thornton's force. With these, seven hundred in number, [Footnote: James says 298 soldiers and about 200 sailors; but Admiral Cochrane in his letter (Jan. 18th) says 600 men, half sailors; and Admiral Codrington also (p. 335) gives this number, 300 being sailors: adding 13 1/3 per cent. for the officers, sergeants, and trumpeters, we get 680 men.] he crossed, but as he did not allow for the current, it carried him down about two miles below the proper landing-place. Meanwhile General Morgan, having under him eight hundred militia [Footnote: 796. (Latour, 164-172.)] whom it was of the utmost importance to have kept together, promptly divided them and sent three hundred of the rawest and most poorly armed down to meet the enemy in the open. The inevitable result was their immediate rout and dispersion; about one hundred got back to Morgan's lines. He then had six hundred men, all militia, to oppose to seven hundred regulars. So he stationed the four hundred best disciplined men to defend the two hundred yards of strong breastworks, mounting three guns, which covered his left; while the two hundred worst disciplined were placed to guard six hundred yards of open ground on his right, with their flank resting in air, and entirely unprotected. [Footnote: Report of Court of Inquiry, Maj.-Gen. Wm. Carroll presiding.] This truly phenomenal arrangement ensured beforehand the certain defeat of his troops, no matter how well they fought; but, as it turned out, they hardly fought at all. Thornton, pushing up the river, first attacked the breastwork in front, but was checked by a hot fire; deploying his men he then sent a strong force to march round and take Morgan on his exposed right flank. [Footnote: Letter of Col. W. Thornton, Jan. 8. 1815.] There, the already demoralized Kentucky militia, extended in thin order across an open space, outnumbered, and taken in flank by regular troops, were stampeded at once, and after firing a single volley they took to their heels. [Footnote: Letter of Commodore Patterson, Jan. 13, 1815.] This exposed the flank of the better disciplined creoles, who were also put to flight; but they kept some order and were soon rallied. [Footnote: Alison outdoes himself in recounting this feat. Having reduced the British force to 340 men, he says they captured the redoubt, "though defended by 22 guns and 1,700 men." Of course, it was physically impossible for the water-battery to take part in the defence; so there were but 3 guns, and by halving the force on one side and trebling it on the other, he makes the relative strength of the Americans just sixfold what it was,—and is faithfully followed by other British writers.] In bitter rage Patterson spiked the guns of his water-battery and marched off with his sailors, unmolested. The American loss had been slight, and that of their opponents not heavy, though among their dangerously wounded was Colonel Thornton.

This success, though a brilliant one, and a disgrace to the American arms, had no effect on the battle. Jackson at once sent over reinforcements under the famous French general, Humbert, and preparations were forthwith made to retake the lost position. But it was already abandoned, and the force that had captured it had been recalled by Lambert, when he found that the place could not be held without additional troops.[Footnote: The British Col. Dickson, who had been sent over to inspect, reported that 2,000 men would be needed to hold the battery; so Lambert ordered the British to retire. (Lambert's letter, Jan. 10th.)] The total British loss on both sides of the river amounted to over two thousand men, the vast majority of whom had fallen in the attack on the Tennesseeans, and most of the remainder in the attack made by Colonel Rennie. The Americans had lost but seventy men, of whom but thirteen fell in the main attack. On the east bank, neither the creole militia nor the Forty-fourth regiment had taken any part in the combat.

The English had thrown for high stakes and had lost every thing, and they knew it. There was nothing to hope for left. Nearly a fourth of their fighting men had fallen; and among the officers the proportion was far larger. Of their four generals, Packenham was dead, Gibbs dying, Keane disabled, and only Lambert left. Their leader, the ablest officers, and all the flower of their bravest men were lying, stark and dead, on the bloody plain before them; and their bodies were doomed to crumble into mouldering dust on the green fields where they had fought and had fallen. It was useless to make another trial. They had learned to their bitter cost, that no troops, however steady, could advance over open ground against such a fire as came from Jackson's lines. Their artillerymen had three times tried conclusions with the American gunners, and each time they had been forced to acknowledge themselves worsted. They would never have another chance to repeat their flank attack, for Jackson had greatly strengthened and enlarged the works on the west bank, and had seen that they were fully manned and ably commanded. Moreover, no sooner had the assault failed, than the Americans again began their old harassing warfare. The heaviest cannon, both from the breastwork and the water-battery, played on the British camp, both night and day, giving the army no rest, and the mounted riflemen kept up a trifling, but incessant and annoying, skirmishing with their pickets and outposts.

The British could not advance, and it was worse than useless for them to stay where they were, for though they, from time to time, were reinforced, yet Jackson's forces augmented faster than theirs, and every day lessened the numerical inequality between the two armies. There was but one thing left to do, and that was to retreat. They had no fear of being attacked in turn. The British soldiers were made of too good stuff to be in the least cowed or cast down even by such a slaughtering defeat as that they had just suffered, and nothing would have given them keener pleasure than to have had a fair chance at their adversaries in the open; but this chance was just what Jackson had no idea of giving them. His own army, though in part as good as an army could be, consisted also in part of untrained militia, while not a quarter of his men had bayonets; and the wary old chief, for all his hardihood, had far too much wit to hazard such a force in fight with a superior number of seasoned veterans, thoroughly equipped, unless on his own ground and in his own manner. So he contented himself with keeping a sharp watch on Lambert; and on the night of January 18th the latter deserted his position, and made a very skilful and rapid retreat, leaving eighty wounded men and fourteen pieces of cannon behind him. [Footnote: Letter of General Jackson, Jan. 19th, and of General Lambert, Jan. 28th.] A few stragglers were captured on land, and, while the troops were embarking, a number of barges, with over a hundred prisoners, were cut out by some American seamen in row-boats; but the bulk of the army reached the transports unmolested. At the same time, a squadron of vessels, which had been unsuccessfully bombarding Fort Saint Philip for a week or two, and had been finally driven off when the fort got a mortar large enough to reach them with, also returned; and the whole fleet set sail for Mobile. The object was to capture Fort Bowyer, which contained less than four hundred men, and, though formidable on its sea-front, [Footnote: "Towards the sea its fortifications are respectable enough; but on the land side it is little better than a block-house. The ramparts being composed of sand not more than three feet in thickness, and faced with plank, are barely cannon-proof; while a sand hill, rising within pistol-shot of the ditch, completely commands it. Within, again, it is as much wanting in accommodation as it is in strength. There are no bomb-proof barracks, nor any hole or arch under which men might find protection from shells; indeed, so deficient is it in common-lodging rooms, that great part of the garrison sleep in tents … With the reduction of this trifling work all hostilities ended." (Gleig, 357.)

General Jackson impliedly censures the garrison for surrendering so quickly; but in such a fort it was absolutely impossible to act otherwise, and not the slightest stain rests upon the fort's defenders.] was incapable of defence when regularly attacked on its land side. The British landed, February 8th, some 1,500 men, broke ground, and made approaches; for four days the work went on amid a continual fire, which killed or wounded 11 Americans and 31 British; by that time the battering guns were in position and the fort capitulated, February 12th, the garrison marching out with the honors of war. Immediately afterward the news of peace arrived and all hostilities terminated.

In spite of the last trifling success, the campaign had been to the British both bloody and disastrous. It did not affect the results of the war; and the decisive battle itself was a perfectly useless shedding of blood, for peace had been declared before it was fought. Nevertheless, it was not only glorious but profitable to the United States. Louisiana was saved from being severely ravaged, and New Orleans from possible destruction; and after our humiliating defeats in trying to repel the invasions of Virginia and Maryland, the signal victory of New Orleans was really almost a necessity for the preservation of the national honor. This campaign was the great event of the war, and in it was fought the most important battle as regards numbers that took place during the entire struggle; and the fact that we were victorious, not only saved our self-respect at home, but also gave us prestige abroad which we should otherwise have totally lacked. It could not be said to entirely balance the numerous defeats that we had elsewhere suffered on land—defeats which had so far only been offset by Harrison's victory in 1813 and the campaign in Lower Canada in 1814—but it at any rate went a long way toward making the score even.

Jackson is certainly by all odds the most prominent figure that appeared during this war, and stands head and shoulders above any other commander, American or British, that it produced. It will be difficult, in all history, to show a parallel to the feat that he performed. In three weeks' fighting, with a force largely composed of militia, he utterly defeated and drove away an army twice the size of his own, composed of veteran troops, and led by one of the ablest of European generals. During the whole campaign he only erred once, and that was in putting General Morgan, a very incompetent officer, in command of the forces on the west bank. He suited his movements admirably to the various exigencies that arose. The promptness and skill with which he attacked, as soon as he knew of the near approach of the British, undoubtedly saved the city; for their vanguard was so roughly handled that, instead of being able to advance at once, they were forced to delay three days, during which time Jackson entrenched himself in a position from which he was never driven. But after this attack the offensive would have been not only hazardous, but useless, and accordingly Jackson, adopting the mode of warfare which best suited the ground he was on and the troops he had under him, forced the enemy always to fight him where he was strongest, and confined himself strictly to the pure defensive—a system condemned by most European authorities, [Footnote: Thus Napier says (vol. v, p. 25): "Soult fared as most generals will who seek by extensive lines to supply the want of numbers or of hardiness in the troops. Against rude commanders and undisciplined soldiers, lines may avail; seldom against accomplished commanders, never when the assailants are the better soldiers." And again (p. 150), "Offensive operations must be the basis of a good defensive system."] but which has at times succeeded to admiration in America, as witness Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Kenesaw Mountain, and Franklin. Moreover, it must be remembered that Jackson's success was in no wise owing either to chance or to the errors of his adversary. [Footnote: The reverse has been stated again and again with very great injustice, not only by British, but even by American writers (as e.g., Prof. W. G. Sumner, in his "Andrew Jackson as a Public Man," Boston, 1882). The climax of absurdity is reached by Major McDougal, who says (as quoted by Cole in his "Memoirs of British Generals," ii, p. 364): "Sir Edward Packenham fell, not after an utter and disastrous defeat, but at the very moment when the arms of victory were extended towards him"; and by James, who says (ii, 388): "The premature fall of a British general saved an American city." These assertions are just on a par with those made by American writers, that only the fall of Lawrence prevented the Chesapeake from capturing the Shannon.

British writers have always attributed the defeat largely to the fact that the 44th regiment, which was to have led the attack with fascines and ladders, did not act well. I doubt if this had any effect on the result. Some few of the men with ladders did reach the ditch, but were shot down at once, and their fate would have been shared by any others who had been with them; the bulk of the column was never able to advance through the fire up to the breastwork, and all the ladders and fascines in Christendom would not have helped it. There will always be innumerable excuses offered for any defeat; but on this occasion the truth is simply that the British regulars found they could not advance in the open against a fire more deadly than they had ever before encountered.] As far as fortune favored either side, it was that of the British [Footnote: E.g.: The unexpected frost made the swamps firm for them to advance through; the river being so low when the levee was cut, the bayous were filled, instead of the British being drowned out; the Carolina was only blown up because the wind happened to fail her; bad weather delayed the advance of arms and reinforcements, etc., etc.]; and Packenham left nothing undone to accomplish his aim, and made no movements that his experience in European war did not justify his making. There is not the slightest reason for supposing that any other British general would have accomplished more or have fared better than he did. [Footnote: "He was the next man to look to after Lord Wellington" (Codrington, i, 339).] Of course Jackson owed much to the nature of the ground on which he fought; but the opportunities it afforded would have been useless in the hands of any general less ready, hardy, and skilful than Old Hickory.

A word as to the troops themselves. The British infantry was at that time the best in Europe, the French coming next. Packenham's soldiers had formed part of Wellington's magnificent peninsular army, and they lost nothing of their honor at New Orleans. Their conduct throughout was admirable. Their steadiness in the night battle, their patience through the various hardships they had to undergo, their stubborn courage in action, and the undaunted front they showed in time of disaster (for at the very end they were to the full as ready and eager to fight as at the beginning), all showed that their soldierly qualities were of the highest order. As much cannot be said of the British artillery, which, though very bravely fought was clearly by no means as skilfully handled as was the case with the American guns. The courage of the British officers of all arms is mournfully attested by the sadly large proportion they bore to the total on the lists of the killed and wounded.

An even greater meed of praise is due to the American soldiers, for it must not be forgotten that they were raw troops opposed to veterans; and indeed, nothing but Jackson's tireless care in drilling them could have brought them into shape at all. The regulars were just as good as the British, and no better. The Kentucky militia, who had only been 48 hours with the army and were badly armed and totally undisciplined, proved as useless as their brethren of New York and Virginia, at Queenstown Heights and Bladensburg, had previously shown themselves to be. They would not stand in the open at all, and even behind a breastwork had to be mixed with better men. The Louisiana militia, fighting in defence of their homes, and well trained, behaved excellently, and behind breastworks were as formidable as the regulars. The Tennesseeans, good men to start with, and already well trained in actual warfare under Jackson, were in their own way unsurpassable as soldiers. In the open field the British regulars, owing to their greater skill in manoeuvring, and to their having bayonets, with which the Tennesseeans were unprovided, could in all likelihood have beaten them; but in rough or broken ground the skill of the Tennesseeans, both as marksmen and woodsmen, would probably have given them the advantage; while the extreme deadliness of their fire made it far more dangerous to attempt to storm a breastwork guarded by these forest riflemen than it would have been to attack the same work guarded by an equal number of the best regular troops of Europe. The American soldiers deserve great credit for doing so well; but greater credit still belongs to Andrew Jackson, who, with his cool head and quick eye, his stout heart and strong hand, stands out in history as the ablest general the United States produced, from the outbreak of the Revolution down to the beginning of the Great Rebellion.

Appendix A

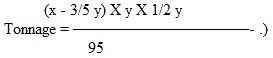

TONNAGE OF THE BRITISH AND AMERICAN MEN-OF-WAR IN 1812-15According to Act of Congress (quoted in "Niles' Register," iv, 64), the way of measuring double-decked or war-vessels was as follows:

"Measure from fore-part of main stem to after-part of stern port, above the upper deck; take the breadth thereof at broadest part above the main wales, one half of which breadth shall be accounted the depth. Deduct from the length three fifths of such breadth, multiply the remainder by the breadth and the product by the depth; divide by 95; quotient is tonnage."

(i.e., if length = x, and breadth = y;

Niles states that the British mode, as taken from Steele's "Shipmaster's Assistant," was this: Drop plumb-line over stem of ship and measure distance between such line and the after part of the stern port at the load water-mark; then measure from top of said plumb-line in parallel direction with the water to perpendicular point immediately over the load water-mark of the fore part of main stem; subtract from such admeasurement the above distance; the remainder is ship's extreme length, from which deduct 3 inches for every foot of the load-draught of water for the rake abaft, and also three fifths of the ship's breadth for the rake forward; remainder is length of keel for tonnage. Breadth shall be taken from outside to outside of the plank in broadest part of the ship either above or below the main wales, exclusive of all manner of sheathing or doubling. Depth is to be considered as one half the length. Tonnage will then be the length into the depth into breadth, divided by 94.

Tonnage was thus estimated in a purely arbitrary manner, with no regard to actual capacity or displacement; and, moreover, what is of more importance, the British method differed from the American so much that a ship measured in the latter way would be nominally about 15 per cent. larger than if measured by British rules. This is the exact reverse of the statement made by the British naval historian, James. His mistake is pardonable, for great confusion existed on the subject at that time, even the officers not knowing the tonnage of their own ships. When the President was captured, her officers stated that she measured about 1,400 tons; in reality she tonned 1,576, American measure. Still more singular was the testimony of the officers of the Argus, who thought her to be of about 350 tons, while she was of 298, by American, or 244, by British measurement. These errors were the more excusable as they occurred also in higher quarters. The earliest notice we have about the three 44-gun frigates of the Constitution's class, is in the letter of Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddart, on Dec. 24, 1798, [Footnote: "American State Papers," xiv, 57.] where they are expressly said to be of 1,576 tons; and this tonnage is given them in every navy list that mentions it for 40 years afterward; yet Secretary Paul Hamilton in one of his letters incidentally alludes to them as of 1,444 tons. Later, I think about the year 1838, the method of measuring was changed, and their tonnage was put down as 1,607. James takes the American tonnage from Secretary Hamilton's letter as 1,444, and states (vol. vi, p. 5), that this is equivalent to 1,533 tons, English. But in reality, by American measurement, the tonnage was 1,576; so that even according to James' own figures the British way of measurement made the frigate 43 tons smaller than the American way did; actually the difference was nearer 290 tons. James' statements as to the size of our various ships would seem to have been largely mere guesswork, as he sometimes makes them smaller and sometimes larger than they were according to the official navy lists. Thus, the Constitution, President, and United States, each of 1,576, he puts down as of 1,533; the Wasp, of 450, as of 434; the Hornet, of 480, as of 460; and the Chesapeake, of 1,244, as of 1,135 tons. On the other hand the Enterprise, of 165 tons, he states to be of 245; the Argus of 298, he considers to be of 316, and the Peacock, Frolic, etc., of 509 each, as of 539. He thus certainly adopts different standards of measurement, not only for the American as distinguished from the British vessels, but even among the various American vessels themselves. And there are other difficulties to be encountered; not only were there different ways of casting tonnage from given measurements, but also there were different ways of getting what purported to be the same measurement. A ship, that, according to the British method of measurement was of a certain length, would, according to the American method, be about 5 per cent. longer; and so if two vessels were the same size, the American would have the greatest nominal tonnage. For example, James in his "Naval Occurrences" (p. 467) gives the length of the __Cyane's__ main deck as 118 feet 2 inches. This same Cyane was carefully surveyed and measured, under orders from the United States navy department, by Lieut. B. F. Hoffman, and in his published report [Footnote: "American State Papers," xiv, p. 417.] he gives, among the other dimensions: "Length of spar-deck, 124 feet 9 inches," and "length of gun-deck 123 feet 3 inches." With such a difference in the way of taking measurements, as well as of computing tonnage from the measurements when taken, it is not surprising that according to the American method the Cyane should have ranked as of about 659 tons, instead of 539. As James takes no account of any of these differences I hardly know how to treat his statements of comparative tonnage. Thus he makes the Hornet 460 tons, and the Peacock and Penguin, which she at different times captured, about 388 each. As it happens both Captain Lawrence and Captain Biddle, who commanded the Hornet in her two successful actions, had their prizes measured. The Peacock sank so rapidly that Lawrence could not get very accurate measurements of her; he states her to be four feet shorter and half a foot broader than the Hornet. The British naval historian, Brenton (vol. v, p. 111), also states that they were of about the same tonnage. But we have more satisfactory evidence from Captain Biddle. He stayed by his prize nearly two days, and had her thoroughly examined in every way; and his testimony is, of course, final. He reports that the Penguin was by actual measurement two feet shorter, and somewhat broader than the Hornet, and with thicker scantling. She tonned 477, compared to the Hornet's 480—a difference of about one half of one per cent. This testimony is corroborated by that of the naval inspectors who examined the Epervier after she was captured by the Peacock. Those two vessels were respectively of 477 and 509 tons, and as such they ranked on the navy lists. The American Peacock and her sister ships were very much longer than the brig sloops of the Epervier's class, but were no broader, the latter being very tubby. All the English sloops were broader in proportion than the American ones were; thus the __Levant_, which was to have mounted the same number of guns as the Peacock, had much more beam, and was of greater tonnage, although of rather less length. The Macedonian, when captured, ranked on our lists as of 1,325 tons, [Footnote: See the work of Lieutenant Emmons, who had access to all the official records.] the United States as of 1,576; and they thus continued until, as I have said before, the method of measurement was changed, when the former ranked as of 1,341, and the latter as of 1,607 tons. James, however, makes them respectively, 1,081, and 1,533. Now to get the comparative force he ought to have adopted the first set of measurements given, or else have made them 1,081 and 1,286. Out of the twelve single-ship actions of the war, four were fought with 38-gun frigates like the Macedonian, and seven with 18-gun brig sloops of the Epervier's class; and as the Macedonian and Epervier were both regularly rated in our navy, we get a very exact idea of our antagonists in those eleven cases. The twelfth was the fight between the Enterprise and the Boxer, in which the latter was captured; the Enterprise was apparently a little smaller than her foe, but had two more guns, which she carried in her bridle ports.