полная версия

полная версияHarper's Young People, December 30, 1879

"But you don't intend us to know where you got it?"

"No, sir," said Rob, frankly.

"Now, papa, you shall not scold Rob," said Bertha, putting her hand in his. "Come into your study. Go away, Rob; go give Jip his supper. Come, mamma;" and Bertha dragged them both in to the fire, where, with sparkling eyes and cheeks like carnation, she began to talk: "Mamma, you remember that scrimmage Rob got into with the village boys last Fourth of July, and how hatefully they knocked him down, and how bruised his eye was for a long time?"

"Yes, I remember, and I always blamed Rob. He should never have had anything to do with those rowdies."

"I didn't blame him; I never blame Rob for anything, except when he won't do what I want him to do. Well, the worst one of all those horrid boys is Sim Jenkins—at least he was; I don't think he's quite so bad now. But he has been punished for all his badness, for he hurt his leg awfully, and has been laid up for months—so his mother says; and she is quite nice. She gave us our dinner to-day. Somehow or other, Rob heard that Sim was in bed, and had not had any Christmas things, and that his mother was poor; and she says all her money has gone for doctor's bills and medicine. And so it just came into his head that perhaps it would do Sim good to have a Christmas-tree on New-Year's Day; and he asked Mrs. Jenkins, and she was afraid it would make a muss, but Rob said he would be careful. And so he carried our tree over, and fixed it in a box, and covered the box with moss, and we have been as busy as bees trying to make it look pretty. And that is what has kept us so long, for Rob had to run down to the store and get things—nails and ribbons, and I don't know what all. And Sim is not to know anything about the tree until to-morrow. And please give us some of the pretty things which were in our box, for we could not get quite enough to fill all the branches. Rob spent so much of his pocket-money on a knife for Sim that he had none left for candy; for he said the tree would not give Sim so much pleasure unless there was something on it which he could always keep."

Here little Bertha stopped for want of breath, and looked into the faces of her listeners.

The parson put his arm around her as he said, "I hardly think we can scold Rob now, after special pleading so eloquent as this; what do you say, mamma?"

"I say that Rob is just like his father in doing this kindly deed, and I am glad to be the mother of a boy who can return good for evil."

The parson made a bow. "Now we are even, madam, in the matter of gracious speeches."

So Sim Jenkins woke up on New-Year's Day to see from his weary bed a vision of brightness—a little tree laden with its fruit of kindness, its flowers of a forgiving spirit; and as the parson preached his New-Year's sermon, and saw Rob's dark eyes looking up at him, he thought of the verse,

"In their young hearts, soft and tender,Guide my hand good seed to sow,That its blossoming may praise TheeWheresoe'er they go."LAFAYETTE'S FIRST WOUND

The Marquis of Lafayette came to this country to give his aid in the struggle for liberty in 1777, and his first battle was that of the Brandywine. Washington was trying to stop the march of the British toward Philadelphia. There was some mistake in regard to the roads, and the American troops were badly beaten. Lafayette plunged into the heart of the fight, and just as the Americans gave way, he received a musket-ball in the thigh. This was the 11th of September. Writing to his wife the next day, he said:

"Our Americans held their ground firmly for quite a time, but were finally put to rout. In trying to rally them, Messieurs the English paid me the compliment of a gunshot, which wounded me slightly in the leg; but that's nothing, my dear heart; the bullet touched neither bone nor nerve, and it will cost nothing more than lying on my back some time, which puts me in bad humor."

But the wound of which the marquis wrote so lightly, in order to re-assure his beloved wife, kept him confined for more than six weeks. He was carried on a boat up to Bristol, and when the fugitive Congress left there, he was taken to the Moravian settlement at Bethlehem, where he was kindly cared for. On the 1st of October he wrote again to his wife:

"As General Howe, when he gives his royal master a high-flown account of his American exploits, must report me wounded, he may report me killed; it would cost nothing; but I hope you won't put any faith in such reports. As to the wound, the surgeons are astonished at the promptness of its healing. They fall into ecstasies whenever they dress it, and protest that it's the most beautiful thing in the world. As for me, I find it a very disgusting thing, wearisome and quite painful. That depends on tastes. But, after all, if a man wanted to wound himself for fun, he ought to come and see how much I enjoy it."

He was very grateful for the attention he received. "All the doctors in America," he writes, "are in motion for me. I have a friend who has spoken in such a way that I am well nursed—General Washington. This worthy man, whose talents and virtues I admire, whom I venerate more the more I know him, has kindly become my intimate friend.... I am established in his family; we live like two brothers closely united, in reciprocal intimacy and confidence. When he sent me his chief surgeon, he told him to care for me as if I were his son, for he loved me as such." This friendship between the great commander, in the prime of life, and the French boy of twenty, is one of the most touching incidents of our history.

The Rock of Gibraltar.—This great natural fortification, which among military men is regarded as the key to the Mediterranean Sea, abounds in caverns, many of which are natural, while others have been made by the explosion of gunpowder in the centre of the mountain, forming great vaults of such height and extent that in case of a siege they would contain the whole garrison. The caverns (the most considerable is the hall of St. George) communicate with the batteries established all along the mountain by a winding road, passable throughout on horseback.

The extreme singularity of the place has given rise to many superstitious stories, not only amongst the ancients, but even those of our own times. As it has been penetrated by the hardy and enterprising to a great distance (on one occasion by an American, who descended by ropes to a depth of 500 feet), a wild story is current that the cave communicates by a submarine passage with Africa. The sailors who had visited the rock, and seen the monkeys, which are seen in no other part of Europe, and are only there occasionally and at intervals, say that they pass at pleasure by means of the cave to their native land. The truth seems to be that they usually live in the inaccessible precipices of the eastern side of the rock, where there is a scanty store of monkey grass for their subsistence; but when an east wind sets in it drives them from their caves, and they take refuge among the western rocks, where they may be seen hopping from bush to bush, boxing each other's ears, and cutting the most extraordinary antics. If disturbed, they scamper off with great rapidity, the young ones jumping on the backs and putting their arms round the necks of the old, and as they are very harmless, strict orders have been received from the garrison for their especial protection.

Gibraltar derives its chief importance from its bay, which is about ten miles in length and eight in breadth, and being protected from the more dangerous winds, is a valuable naval station.

SANTA CLAUS VISITS THE VAN JOHNSONS

Swing low, sweet chariot—Goin' fur to car' me home;Swing low, sweet chariot—Goin' fur to car' me home.Debbil tought he would spite me—Goin' fur to car' me home,By cuttin' down my apple-tree—Goin' fur to car' me home;But he didn't spite ah-me at all—Goin' fur to car' me home;Fur I had apples all de fall—Goin'—"Oh, jess shut up wiff yo' ole apples, Chrissfer C'lumbus Van Johnson, an' lissen at dat ar wat Miss Bowles done bin a-tellin' me," said Queen Victoria, suddenly making her appearance at the gate which opened out of Mrs. Bowles's back garden into the small yard where her brother sat with Primrose Ann in his arms.

The Van Johnsons were a colored family who lived in a Southern city in a small three-roomed wooden house on the lot in the rear of Mrs. Bowles's garden, and Mrs. Bowles was their landlady and very good friend. Indeed, I don't know what they would have done without her, for when she came from the North, and rented the big house, they were in the depths of poverty. The kind lady found them work, gave them bright smiles, words of encouragement, fruit, vegetables, and spelling lessons, and so won their simple, grateful hearts that they looked upon her as a miracle of patience, goodness, and wisdom. And as for Baby Bowles—the rosy-cheeked, sweet-voiced, sunshiny little thing—the whole family, from Primrose Ann up to Mr. Van Johnson, adored her, and Queen Victoria was "happy as a queen" when allowed to take care of and amuse her.

"Wat's dat ar yo's speakin'?" asked Christopher Columbus (so named, his father said, "'cause he war da fustest chile, de discoberer ob de family, as it war") as Queen Victoria hopped into the yard on one leg, and he stopped rocking—if you can call throwing yourself back on the hind-legs of a common wooden chair, and then coming down on the fore-legs with a bounce and a bang, rocking—the youngest Van Johnson with such a jerk that her eyes and mouth flew open, and out of the latter came a tremendous yell. "Dar now," said Christopher Columbus, "yo's done gone an' woked dis yere Primrose Ann, an' I's bin hours an' hours an' hours an' hours gittin her asleep. Girls am de wustest bodders I ebber see. I allus dishated girls."

"Ain't yo' 'shamed yo'seff, Chrissfer C'lumbus," said Queen Victoria, indignantly, "wen bofe yo' sisters am girls? But spect yo' don't want to lissen at wat Miss Bowles done bin a-tellin' me. Hi! Washington Webster's a-comin', an' I'll jess tell him dat ar secrek all by hisseff."

"No yo' won't; yo' goin' to tell me too," said her big brother. "An' yo' better stop a-rollin' yo' eyes—yo' got de sassiest eyes I ebber see since de day dat I war bohn—an' go on wiff yo' story."

"Story?" repeated Washington Webster, sauntering up to them, leading a big cat—dragging, perhaps, would be the better word, as poor puss was trying hard to get away—by a string.

"'Bout Mahser Zanty Claws," said Queen, opening her eyes so wide that they seemed to spread over half her face. "Miss Bowles says to-morrer's Chrissmus, an' to-day's day befo' Chrissmus, an' to-night Mahser Zanty Claws go 'bout"—lowering her voice almost to a whisper—"an' put tings in chillun's stockin's dat 'haved deirselbs."

"Am Mahser Zanty Claws any lashun to dat ar ole man wiff de allspice hoof?" asked Washington Webster, with a scared look.

"Allspice hoof! Lissen at dat ar foolish young crow. Clove hoof, yo' means," said Queen Victoria. "Dat's anodder gemman 'tirely. Mahser Zanty Claws am good. He gits yo' dolls, an' candies, an' apples, an' nuts, an' books, an' drums, an' wissels, an' new cloze."

"Golly! wish he'd frow some trowsus an' jackits an' sich like fruit 'roun' here," said Christopher Columbus.

"Trowsus wiff red 'spenders an' a pistil pockit," said Washington Webster, "an' a gole watch, an' a sled all yaller, wiff green stars on it, an'—"

"Yo' bofe talk 's if yo'd bin awful good," interrupted Queen Victoria. "Maybe Mahser Zanty Claws disagree wiff yo'."

"Who dat ar done gone git her head cracked wiff de wooden spoon fur gobblin' all de hom'ny befo' de breakfuss war ready?" said Washington Webster, slyly.

"I 'most wish dar war no Washington Websters in de hull worle—I certainly do. Dey's too sassy to lib," said Queen Victoria. "An' sich busybodies—dey certainly is."

"But how am we to know wedder we's Mahser Zanty Claws's kine o' good chillun?" said Christopher Columbus. "We's might be good nuff fur ourseffs, an' not good nuff fur him. If I knowed he come yere certain sure, I git some green ornamuntses from ole Pete Campout—he done gone got hunderds an' hunderds an' piles an' piles—to stick up on de walls, an' make de house look more despectable like."

"Let's go an' ax Miss Bowles," said Queen Victoria. "Baby Bowles am fass asleep, an' she's in de kitchen makin' pies, an' she know ebberyting—she certainly do."

And off they all trooped, Primrose Ann, cat, and all.

"Come in," called the pleasant voice of their landlady, when they rapped on her door; and in they tumbled, asking the same question all together in one breath: "Mahser Zanty Claws comin' to our house, Miss Bowles?" Christopher Columbus adding, "'Pears dough we muss ornamentem some if he do."

Mrs. Bowles crimped the edge of her last pie, and then sat down, the children standing in a row before her.

"Have you all been very good?" she said. "Suppose you tell me what good thing you have done since yesterday afternoon. Then I can guess about Santa Claus."

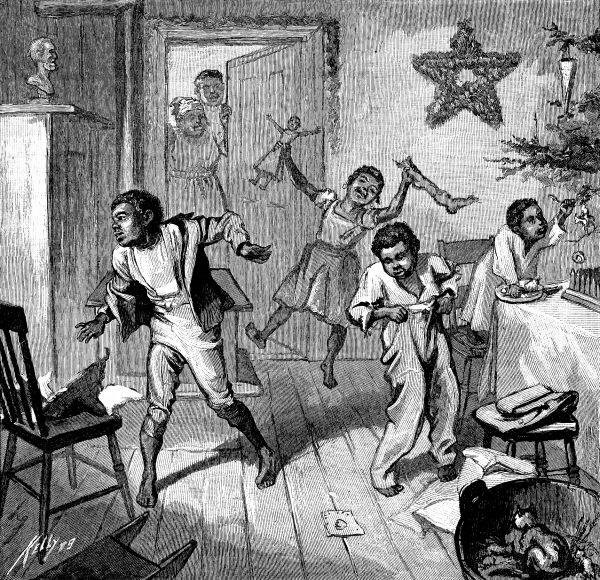

"LOR BRESS YOU, HONEY-BUGS! YO' HAS GOT TINGS MIXED."—Drawn by J. E. Kelly.

"Primrose Ann cried fur dat ar orange yo' gib me," said Queen Victoria, after a moment's thought, "an' I eat it up quick 's I could, an' didn't gib her none, 'cause I's 'fraid she git de stummick-ache."

"I car'd home de washin' fur mommy fur two cakes an' some candy," said Washington Webster.

"And you?" asked Mrs. Bowles, turning to Christopher Columbus.

"I ran 'way from 'Dolphus Snow, an' wouldn't fight him, 'cause I 'fraid I hurt him," said Christopher, gravely.

Mrs. Bowles laughed merrily. "Go home and ornament," she said. "I am sure Santa Claus will pay you a visit."

And he did; for on Christmas morning, when the young Van Johnsons rushed pell-mell, helter-skelter, into the room prepared for his call, a new jacket hung on one chair, a new pair of trousers on the other; a doll's head peeped out of Queen Victoria's stocking; a new sled, gayly painted, announced itself in big letters "The Go Ahead"; lots of toys were waiting for Primrose Ann; and four papers of goodies reposed on the lowest shelf of the cupboard.

"'Pears dat ar Mahser Zanty Claws don't take zact measure fur boys' cloze," said Christopher Columbus, as he tried to struggle into the jacket. "Dis yere jackit's twicet too small."

"An' dis yere trowsusloons am twicet too big," said Washington Webster, as he drew them up to his armpits.

"Lor' bress you, honey-bugs!" called their mommy from the doorway, "yo' has got tings mixed. Dat ar jackit's fur de odder boy, an' dem trowsus too." And they all burst out laughing as Christopher Columbus and Washington Webster exchanged Christmas gifts, and laughed so loud that Mrs. Bowles came, over to see what was the matter, bringing Baby Bowles, who, seeing how jolly everybody was, began clapping her tiny hands, and shouting, "Melly Kissme! melly Kissme!"

ONE HUNDRED YEARS AGO.—Drawn by Kate Greenaway.

PET AND HER CAT

Now, Pussy, I've something to tell you:You know it is New-Year's Day;The big folks are down in the parlor,And mamma is just gone away.We are all alone in the nursery,And I want to talk to you, dear;So you must come and sit by me,And make believe you hear.You see, there's a new year coming—It only begins to-day.Do you know I was often naughtyIn the year that is gone away?You know I have some bad habits,I'll mention just one or two;But there really is quite a numberOf naughty things that I do.You see, I don't learn my lessons,And oh! I do hate them so;I doubt if I know any more to-dayThan I did a year ago.Perhaps I am awfully stupid;They say I'm a dreadful dunce.How would you like to learn spelling?I wish you could try it once.And don't you remember Christmas—'Twas naughty, I must confess—But while I was eating my dinnerI got two spots on my dress.And they caught me stealing the sugar;But I only got two little bits,When they found me there in the closet,And frightened me out of my wits.And, Pussy, when people scold me,I'm always so sulky then;If they only would tell me gently,I never would do it again.Oh, Pussy! I know I am naughty,And often it makes me cry:I think it would count for something,If they knew how hard I try.But I'll try again in the new year,And oh! I shall be so gladIf I only can be a good little girl,And never do anything bad!HOW SUNKEN SHIPS ARE RAISED

When a ship sinks some distance from the shore in several fathoms of water, and the waves conceal her, it may seem impossible to some of our readers that she can ever be floated again; but if she rests upon a firm sandy bottom, without rocks, and the weather is fair enough for a time to give the wreckers an opportunity, it is even probable that she can be brought into port.

In Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk, and New Orleans, large firms are established whose special business it is to send assistance to distressed vessels, and to save the cargo if the vessels themselves can not be prevented from becoming total wrecks; and these firms are known as wreckers—a name which in the olden time was given to a class of heartless men dwelling on the coast who lured ships ashore by false lights for the sake of the spoils which the disaster brought them.

When a vessel is announced to be ashore or sunk, the owners usually apply to the wreckers, and make a bargain with them that they shall receive a certain proportion of her value if they save her, and the wreckers then proceed to the scene of the accident, taking with them powerful tug-boats, large pontoons, immense iron cables, and a massive derrick.

Perhaps only the topmasts of the wreck are visible when they reach it; but even though she is quite out of sight, she is not given up, if the sea is calm and the wind favorable. One of the men puts a diving dress over his suit of heavy flannels. The trousers and jacket are made of India rubber cloth, fitting close to the ankles, wrists, and across the chest, which is further protected by a breastplate. A copper helmet with a glass face is used for covering the head, and is screwed on to the breastplate. One end of a coil of strong rubber tubing is attached to the back of the helmet, to the outside of which a running cord is also attached, and continued down the side of the dress to the diver's right hand, where he can use it for signaling his assistants when he is beneath the surface. His boots have leaden soles weighing about twenty-eight pounds; and as this, with the helmet, is insufficient to allow his descent, four blocks of lead, weighing fifty pounds, are slung over his shoulders; and a water-proof bag containing a hammer, a chisel, and a dirk-knife is fastened over his breast.

He is transferred from the steamer that has brought him from the city to a small boat, which is rowed to a spot over the wreck, and a short iron ladder is put over the side, down which he steps; and when the last rung is reached, he lets go, and the water bubbles and sparkles over his head as he sinks deeper and deeper.

The immersion of the diver is more thrilling to a spectator than it is to him. The rubber coil attached to his helmet at one end is attached at the other to an air-pump, which sends him all the breath he needs, and if the supply is irregular, a pull at the cord by his right hand secures its adjustment. He is not timid, and he knows that the only thing he has to guard against is nervousness, by which he might lose his presence of mind. The fish dart away from him at a motion of his hand, and even a shark is terrified by the apparition of his strange globular helmet. He is careful not to approach the wreck too suddenly, as the tangled rigging and splinters might twist or break the air-pipe and signal line; when his feet touch the bottom, he looks behind, before, and above him before he advances an inch.

Looming up before him like a phantom in the foggy light is the ship; and now, perhaps, if any of the crew have gone down with her, the diver feels a momentary horror; but if no one has been lost, he sets about his work, and hums a cheerful tune.

It may be that the vessel has settled low in the sand, that she is broken in two, or that the hole in her bottom can not be repaired. But we will suppose that the circumstances are favorable, that the sand is firm, and the hull in an easy position.

The diver signals to be hauled up, makes his report, and in his next descent he is accompanied by several others, who help him to drag massive chains of iron underneath the ship, at the bow, at the stern, and in the middle. This is a tedious and exhausting operation, which sometimes takes many days; and when it is completed, the pontoons are towed into position at each side of the ship.

The pontoons, simply described, are hollow floats. They are oblong, built of wood, and possess great buoyancy. Some of them are over a hundred feet long, eighteen feet wide, and fourteen feet deep; but their size, and the number of them used, depend on the length of the vessel that is to be raised. Circular tubes, or wells, extend through them; and when the chains are secured underneath the ship, the ends are inserted in these wells by the divers, and drawn up through them by hydraulic power. The chains thus form a series of loops like the common swing of the playground, in which the ship rests; and as they are shortened in being drawn up through the wells, the ship lifts. The ship lifts if all be well—if the chains do not part, or some other accident occur; but the wreckers need great patience, and sometimes they see the labor of weeks undone in a minute.

We are presupposing success, however, and instead of sinking or capsizing, the ship appears above the bubbling water, and between the pontoons, which groan and tremble with her weight.

As soon as her decks are above water, so much of the cargo is removed as is necessary to enable the divers to reach the broken part of the hull, which they patch with boards and canvas if she is built of wood, or with iron plates if she is of iron. This is the most perilous part of the diver's work, as there are so many projections upon which his air-tube may catch; but he finds it almost as easy to ply his hammer and drill in making repairs under water as on shore.

The ship is next pumped out, and borne between the pontoons by powerful tugs to the nearest dry-dock, where all the damages are finally repaired, and in a month or two she is once more afloat, with nothing to indicate her narrow escape.

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGEN AND NYCTERIS

XVI.—AN EVIL NURSE

Watho was herself ill, as I have said, and was the worse tempered; and, besides, it is a peculiarity of witches that what works in others to sympathy, works in them to repulsion. Also, Watho had a poor, helpless, rudimentary spleen of a conscience left, just enough to make her uncomfortable, and therefore more wicked. So when she heard that Photogen was ill she was angry. Ill, indeed! after all she had done to saturate him with the life of the system, with the solar might itself! He was a wretched failure, the boy! And because he was her failure, she was annoyed with him, began to dislike him, grew to hate him. She looked on him as a painter might upon a picture, or a poet upon a poem, which he had only succeeded in getting into an irrecoverable mess. In the hearts of witches love and hate lie close together, and often tumble over each other. And whether it was that her failure with Photogen foiled also her plans in regard to Nycteris, or that her illness made her yet more of a devil's wife, certainly Watho now got sick of the girl too, and hated to have her about the castle.

She was not too ill, however, to go to poor Photogen's room and torment him. She told him she hated him like a serpent, and hissed like one as she said it, looking very sharp in the nose and chin, and flat in the forehead. Photogen thought she meant to kill him, and hardly ventured to take anything brought him. She ordered every ray of light to be shut out of his room; but by means of this he got a little used to the darkness. She would take one of his arrows, and now tickle him with the feather end of it, now prick him with the point till the blood ran down. What she meant finally I can not tell, but she brought Photogen speedily to the determination of making his escape from the castle: what he should do then he would think afterward. Who could tell but he might find his mother somewhere beyond the forest! If it were not for the broad patches of darkness that divided day from day, he would fear nothing!