полная версия

полная версияLippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. 22, August, 1878

The building on the Champ de Mars is 2132 feet by 1148. A wide and lofty vestibule runs across the full extent of each end, and these afford the most imposing interior views of the building. They are known respectively as the Galérie d'Iéna and Galérie de l'École Militaire, from their vicinity to the bridge and school respectively. Being lofty themselves, and having central and flanking domed towers which break the uniformity, their fronts form the principal façades of the building, of which, architecturally speaking, they are the principal entrances; but in fact, as happens with buildings of such acreage, the actual inlets depend upon the predominance in numbers of the people on one or another side of the building, the means of approach by land and water, and the contiguous streets of favorite and convenient travel. In the present case the bulk of the people reach the grounds either by water at the south-east corner or by land at the intersection of Avenue Rapp with the Avenue Bourdonnaye, which latter bounds the Champ de Mars on its southern side.

The end-vestibules are connected by five longitudinal galleries on each side of the open area in the middle of the building. The five galleries on the southern side belong to France, and the five on the northern side are divided by transverse partitions among the foreign nations present, in very greatly differing quantities. England, for instance, occupies nearly two-sevenths of the whole space devoted to foreign exhibitors, being more than the sum of the amounts allotted to Spain, China, Japan, Italy, Sweden, Norway and the United States. The end-vestibules have curved roofs with highly ornamented ceilings of a succession of flat domes along the centres, with three rows of deep soffits on each side, gayly painted. The walls are nearly all glass in iron frames, and the panes of white glass alternate in checkerwork with those having blue tracery upon them. The whole building is principally of iron and glass, the roof of wood, with zinc plates and numerous skylights over the interior galleries. The machinery galleries of each side are much the largest of the longitudinal ones, and have high roofs with side windows above the levels of the roofs on each side of them; but the four other galleries on each side of the building have quite low ceilings, which make one fear for the quality of the ventilation when the heat is at its greatest.

In the interior of the quadrangular building is an open space about two hundred feet broad and nearly two thousand feet long, reaching from one vestibule to the other; and in this space are two rows of fine-art pavilions and a building for the exhibition of the municipal works of the city. This isolated building is in the central portion of the whole structure, the fine-art pavilions being arranged in line with it, four in a group, the salons of a group connected by lobbies and also with the large end-vestibules at the end upon which they abut.

The French and foreign sides of the Exposition building on the Champ de Mars have frontages upon the interior court, and the façades of the foreign sections are made ornamental and are intended to be characteristic of the countries. There is a great discrepancy in the space assigned to each: that of Great Britain is the longest, amounting to five hundred and forty feet in length, while the little territories of Luxembourg, Andorra, Monaco and San Marino, which are clubbed together, have unitedly about twenty-five feet of frontage. In some cases the space assigned to a nation does not run back the full four hundred feet to the outside of the building, but it is intended that each shall have some part of the façade in this allée. Much taste and more expense have been lavished upon the architectural construction and embellishment of the façades, and the row reminds one of the scenes in a theatre, where palace, cottage, mosque and jail stand side by side, giving a particolored effect as various as the different emotions which the respective buildings might be supposed to elicit. The English space being so large, no single design was adopted, as it could have but a monotonous effect, but the frontage was divided into five portions, each of which illustrates some style of villa or cottage architecture, and is separated from the adjoining one by garden-beds. The first, counting from the Salle de la Seine, is of the style of Queen Anne's reign. It is built of a patented imitation of red brickwork. Thin slabs of Portland cement concrete are faced with smaller slabs of red concrete of the size of bricks and screwed to the wooden frame of the building. The house has tall casements in a bay with a balcony, and an entablature on top of the wall. The second house is the pavilion of the prince of Wales, and is of the Elizabethan style. It is built of rubble-work faced with colored plaster in imitation of red brickwork and Bath-stone dressings. The front has niches for statuary, and above the windows are shield-shaped panels for armorial bearings. The windows are in square clusters, with small lights in hexagonal leaden cames. The union jack flies from the staff. The third house is constructed of red brick and terra-cotta, and is not specially characteristic of any period. It is, in fact, a jumble of the early Gothic with a Moorish entablature and a balustrade parapet. The stained-glass casement windows are surmounted with circular lights in the arches. The fourth house is built of pitch-pine framework, enriched with carving and filled in with plaster panels—a style of construction known as "half-timbered work," much employed in England from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century. This house is placed at the disposal of the Canadian commissioners. It has a large square two-story bay-window, with the customary small glass panes in cames of lozenge and other patterns, and is perhaps the neatest and most cozy house in the row. The fifth is of the construction of an English country-house in the reign of William III. It is of timber, with stucco and rough-cast panels, and has a large bay-window in the second story, surmounted by a gable to the street and covering an old-fashioned stoop with seats on each side. The five houses have a pretty effect, and each has a home look. The façades only are on exhibition, the interiors being private. They contrast with others in the "street" in the same way as the habits of the different peoples. Some build their houses to retire into, and others to exhibit themselves. Each nation being asked for the façade of a house, the Italian has built a portico where he can lounge, see and be seen; the Englishman has in all serenity represented what he deems comfort, and shuts the front door.

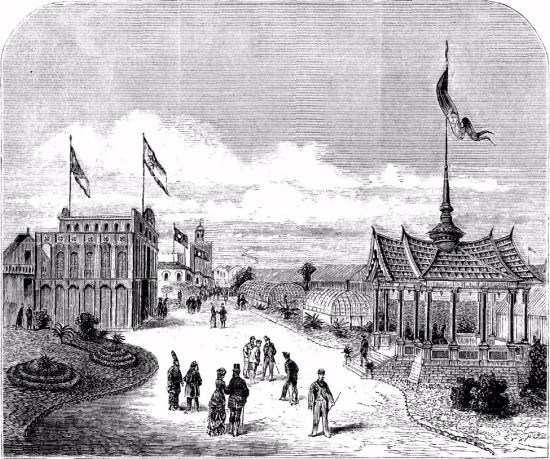

VIEW IN THE PARK OF THE TROCADÉRO, SHOWING THE PAVILIONS OF PERSIA AND SIAM.

The next in order is the United States house, which is plain and commodious; the latch-string would be out, but that the front door is everlastingly open. The style is perhaps to advertise to the world that we have not yet had time to invent an order of architecture or devise anything adapted to our climate, which has extremes utterly unknown to our ancestors in Britain. The building is light and airy, has office-rooms on each floor, and is described by one English paper as "a sort of school-building which combines elegance with usefulness." Another paper states that "it exemplifies the utilitarian notions of our Transatlantic cousins rather than any artistic intent." These comments are as favorable as anything we ourselves can say: we accept the verdict with thanks and think we have got off pretty well. In the squareness of its general lines, with arched windows on the second floor and square tower over the centre, perhaps the architect thought it was Italian. Sixteen coats-of-arms on the outside excite admiration.

The building of Norway and Sweden is a charming cottage of handsome and ample proportions. It has three sections: one of two stories with low-pitched roof, and gable to the street, a middle structure with colonnade, and one of three stories with high-pitched roof. The windows are round-topped, made in an ingenious way, the upper member being an arched piece with sloping ends, to match the springing on the tops of the posts which divide the openings. The horizontal and vertical bands are enriched by carving.

The façade of Italy may be pronounced pretentious and disappointing. It is constructed of various kinds of unpolished marble and terra-cotta panels. A tall archway is flanked by two wings having each two smaller arches, the entablatures of which are enriched, if we must so term it, with gaudy mosaic figures, portraits and heraldic bearings, while the spans of the arches surmount pyramidal groups of emblems, scientific, medical, lyrical and so forth. Red curtains with heavy gilt cords and tassels behind the arches throw the columns with composition (not Composite) capitals and the emblems into high relief. Beneath the centre arch is the armorial bearing of the country. The vestibules display statuary.

Japan has a quaint little house with a very massive gateway of solid timber, flanked by two characteristic fountains of terra-cotta. These represent stumps of trees, with gigantic lily-cups, leaves of water-lilies, and frogs in grotesque attitudes in and around the water.

China has a grotesque house, painted in imitation of octagonal slate-colored bricks, covered with a pagoda-roof full of curves and points. The red door has rows of large knobs and is surmounted by colored and gilded carvings, representing genii probably. The pointed flag has in a yellow field a blue dragon in the later stages of consumption.

Spain has a Moorish building rich in gold and color—a central portion with Italian roof, and two colonnade side-sections flanked by castellated towers. Five forms of arches span the doors and windows, and the artist has contrived to associate all forms of ornament, running from an approach to the Greek fret down through the Arabesque to the Brussels carpet.

Austro-Hungary has a long colonnade of white stone ornamented with black filigree-work and supported by columns in pairs. The entablature is surmounted by a row of statues, and the end-towers have parapets with balustrade. The colonnade, with a chocolate-brown back wall, affords shelter and relief for bronze and marble statuary. At each end of this façade is a tall flagstaff striped like a barber's pole, and so familiar to all who have visited the Austrian stations, at Trieste, for example. From it flies the flag of horizontal stripes of red, white and green, with the shield of many quarterings and two angelic supporters.

Russia has a log-and-frame house of somewhat more than average picturesque character. The projecting centres and wing-towers, the outside staircase, and roofs conical, flat, pyramidal, bulbous and Oriental, give it a miscellaneous toyshop appearance, characteristic perhaps of the mosaic character of the nation. Barge-boards and brackets of various cheap patterns are plentifully strewed over the building.

Passing from the Russian to the Swiss building suggests inevitably Mr. Mantalini's description of his former chères amies: "The two countesses had no outline at all, and the dowager's was a demmed outline." A semicircular archway, over which is a high-flying arch with a roof of six slopes surmounted by a bell-tower and pinnacle roof; on the pillars two lions supporting a red shield with white Greek cross in the field; two wings with flat arches containing gorgeous stained-glass windows. But what avails description? There are twenty-two armorial bearings on the spandrils of the arches, beating the United States by six; but we had only room for the original thirteen, the United States and two more. Oh that they had granted us more space! High up aloft is the motto Un pour tous, tons pour un, which was adopted by the French Commune.

Belgium is pre-eminent in the whole row, if expense determines. This country has about three times as much space in the building as the United States, and has worthily filled it. The Belgian façade on the "Street of Nations" is reputed to have cost nearly as much as the whole appropriation made by Congress for the United States exhibit. It is of dark red brick with gray stone quoins and corners and blue and gray marble pillars. The centre building is joined by two colonnades to a flanking tower at one end and an ornate gable at the other. The style is one familiar in the times when the great William of Orange was alive, and was to some extent introduced into England soon after another William took the place of his bigoted father-in-law. It cannot be denied that the general effect is gray, sombre and uncomfortable—that it is too much crowded with objects, and, though of admirable and enduring materials, suggests a spasmodic attempt to assimilate itself to the gala character of the occasion which called it forth. It is the saturnine one of the row. It is said that the pieces are numbered for re-erection in some other place.

Greece has an Athenian house painfully crude in color, white picked out with all the hues of the rainbow and some others, suggesting muddy coffee and chibouques.

Denmark has about twenty feet of front, utilized by a gable-end of brick with facings of imitation stone.

The Central American States have about sixty feet of yellow front, with three arched openings into the vestibule, which is flanked by a tower and a gable.

Anam, Persia, Siam, Morocco and Tunis have unitedly a gingerbread affair of four distinct patterns—we cannot call them styles. Siam in the centre has a chocolate-colored tower picked out with silver, and surmounted by a triple pagoda roof, whence floats the flag, a white elephant in a red field. The six feet of homeliness belonging to Tunis has a balcony of wood which neither reveals nor hides the almond-eyed whose supposed relatives are selling trumpery in booths on the other side of the Seine.

Luxembourg, Andorra, Monaco and San Marino unite in a façade representing the different styles of architecture which prevail in the several states: 1. A portion faintly suggesting the ancient palace of Luxembourg, to-day the residence of Prince Henry of Holland; 2. An entrance erected by the principality of Monaco as the model of that of the royal palace; 3. A window contributed by San Marino, and showing that the prevalent type in the little republic is more useful than ornamental; 4. A balustrade surmounting the façade, supplied by the republic of Andorra.

Portugal has an imitation in cream-colored plaster of a Gothic church-entrance, and a highly-enriched arch with flanking towers, whose canopied niches have figures of warriors and wise men.

Holland shows an architecture of two hundred years ago, the counterpart of the houses we see in the old Dutch pictures. It is of dark red brick with stone courses, and a tall slate roof behind its balustered parapet.

We are at the end of the Street of Nations, somewhat under a third of a mile in length.

It is evening, and the sun in this latitude—for we are farther north than Quebec—seems in no hurry to reach the horizon. Two hours ago the whistle sounded "No more steam," and the life of the building went out. The attendants, tired of the show and blasés or "used up," according to their nationality, with exhibitions, have shrouded their cases in sack-cloth and gone to sip ordinaire, absinthe or bitter ale. I sit on a terrace of the Champ de Mars, the gorgeous building at my back, and look riverward. Before me stretches away the green carpet of sward one hundred feet wide and six hundred long, a broad level band of emerald reaching to the gravel approach to the Pont d'Iéna, each side of which is guarded by a colossal figure of a man leading a horse. The gravel around the tapis vert is black with the figures of those whom the fineness of the evening has induced to take a parting stroll in the ground before retiring.

Flanking the gravel-walks the ground is more uneven, and Art, in imitation of the wilder aspects of Nature, has done what the limited space permitted to enhance the allied beauties of land and water, where

Each gives each a double charm,Like pearls upon an Ethiop's arm.On the left is a rockery and waterfall on no mean scale, with a romantic little lake in front. On the right a rocky island in a corresponding lake is crowned with a thatched pavilion, the reflection of which shines broken in the water ruffled by the evening breeze. Groups of detached buildings hem in the view on each side, and their flags wave with the sky for a background. Paris is invisible: at this point the grounds are isolated from outside view.

Rising clear beyond the bridge, the approach to it on the other side hidden by the lowness of the point of view, stands the palace of the Trocadéro, a broad sweep of green covering the hill, along whose summit are the widespread wings of the colonnade, uniting at the central rotunda, of which the domed roof and square campaniles rise one hundred feet above all and dominate the middle of the picture. The traces of the indefatigable swarms of workmen are obliterated, except in the magical and finished work. The spray of the fountains of the château d'eau drifts to leeward and hides at times patches of the velvety grass on the hill. The central jet plays sturdily, and from where I sit appears to reach the level of the second corridor of the rotunda.

The eye fails to detect a single object, excepting the four statues on the bridge, which is not the creation of a few months. The hill beyond has been torn to pieces and sloped, and the palace built upon it. Every house in sight is new. The very ground in front on which I look down has been raised, and the terrace on which I sit has been built. The ponds have been excavated, the mimic rocky hills have been piled up, and the water led to the brink of the tiny precipice from the artesian wells which supply this part of Paris.

The hum of many voices and the dash of waters make a deep undertone, and one comes away with the feeling—not exactly that the scene is too good to last, but—of regret that the result of such lavish care should be ephemeral. In a few months all on the left side of the river may again be parade-ground, and the thirty thousand troops which can be readily manœuvred upon it be getting ready for another conflict, while the palace which the Genius of the Lamp had builded, as in a night, shall be a thing of the past, as if whirled away by the malevolent magician.

Edward H. Knight.SENIORITY

Child! Such thou seemest to me that am more oldIn sorrow than in years,With that long pain that turns us bitter cold,Far worse than these hot tearsOf thine, that fall so fast upon my breast.I know they ease thy grief:I know they comfort, and will bring thee rest,Thou poor wind-shaken leaf!Ah yes, thy storm will pass, thy skies will clear.Thou smilest beneath my kiss:Lift up the blue eyes cleansed by weeping, dear,Of every thought amiss.What seest thou, child, in these dry eyes of mine?Grief that hath spent its tears—Grief that its right to weeping must resign,Not told by days, but years.The bitterest is that weeping of the heartThat mounts not to the eyes:In its lone chamber we sit down apart,And no one hears our cries.It comes to this with every deep, true soul:'Tis neither kill nor cure,But a strong sorrow held in strong control,A girding to endure.For no such soul lives in this tangled worldBut, like Achilles' heel,Hath in the quick a shaft too truly hurled—Flesh growing round the steel.And with its outcome would come all Life's flood:Joy is so twined with pain,Sweetness and tears so blended in our blood,They will not part again.For at the last the heart grows round its grief,And holds it without strife:So used we are, we cry not for relief,For we know all of life.And this is why I kiss thy tear-wet eyes,Nor think thy grief so great.Thou untried child! at every fresh surpriseThy heart springs to the gate.Howard Glyndon."FOR PERCIVAL."

CHAPTER XXXV.

OF THE LANDLADY'S DAUGHTER

Early in that December the landlady's daughter came home. Percival could not fix the precise date, but he knew it was early in the month, because about the eighth or ninth he was suddenly aware that he had more than once encountered a smile, a long curl and a pair of turquoise earrings on the stairs. He had noticed the earrings: he could speak positively as to them. He had seen turquoises before, and taken little heed of them, but possibly his friends had happened to buy rather small ones. He felt pretty certain about the long curl. And he thought there was a smile, but he was not so absolutely sure of the smile.

By the twelfth he was quite sure of it. It seemed to him that it was cold work for any one to be so continually on the stairs in December. The owner of the smile had said, "Good-morning, Mr. Thorne."

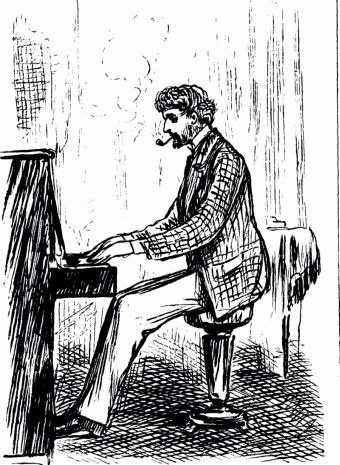

On the thirteenth a question suggested itself to him: "Was she—could she be—always running up and down stairs? Or did it happen that just when he went out and came back—?" He balanced his pen in his fingers for a minute, and sat pondering. "Oh, confound it!" he said to himself, and went on writing.

That evening he left the office to the minute, and hurried to Bellevue street. He got halfway up the stairs and met no one, but he heard a voice on the landing exclaim, "Go to old Fordham's caddy, then, for you sha'n't—Oh, good gracious!" and there was a hurried rustle. He went more slowly the rest of the way, reflecting. Fordham was another lodger—elderly, as the voice had said. Percival went to his sitting-room and looked thoughtfully into his tea-caddy. It was nearly half full, and he calculated that, according to the ordinary rate of consumption, it should have been empty, and yet he had not been more sparing than usual. His landlady had told him where to get his tea: she said she found it cheap—it was a fine-flavored tea, and she always drank it. Percival supposed so, and wondered where old Fordham got his tea, and whether that was fine-flavored too.

There was a giggle outside the door, a knock, and in answer to Percival's "Come in," the landlady's daughter appeared. She explained that Emma had gone out shopping—Emma was the grimy girl who ordinarily waited on him—so, with a nervous little laugh, with a toss of the long curl, which was supposed to have got in the way somehow, and with the turquoise earrings quivering in the candlelight, she brought in the tray. She conveyed by her manner that it was a new and amusing experience in her life, but that the burden was almost more than her strength could support, and that she required assistance. Percival, who had stood up when she came in and thanked her gravely from his position on the hearthrug, came forward and swept some books and papers out of the way to make room for her load. In so doing their hands touched—his white and beautifully shaped, hers clumsy and coarsely colored. (It was not poor Lydia's fault. She had written to more than one of those amiable editors who devote a column or two in family magazines to settling questions of etiquette, giving recipes for pomades and puddings, and telling you how you may take stains out of silk, get rid of freckles or know whether a young man means anything by his attentions. There had been a little paragraph beginning, "L.'s hands are not as white as she could wish, and she asks us what she is to do. We can only recommend," etc. Poor L. had tried every recommendation in faith and in vain, and was in a fair way to learn the hopelessness of her quest.)

The touch thrilled her with pleasure and Thorne with repugnance. He drew back, while she busied herself in arranging his cup, saucer and plate. She dropped the spoon on the tray, scolded herself for her own stupidity, looked up at him with a hurried apology, and laughed. If she did not blush, she conveyed by her manner a sort of idea of blushing, and went out of the room with a final giggle, being confused by his opening the door for her.

Percival breathed again, relieved from an oppression, and wondered what on earth had made her take an interest in his tea and him. Yet the reason was not far to seek. It was that tragic, melancholy, hero's face of his—he felt so little like a hero that it was hard for him to realize that he looked like one—his sombre eyes, which might have been those of an exile thinking of his home, the air of proud and rather old-fashioned courtesy which he had inherited from his grandfather the rector and developed for himself. Every girl is ready to find something of the prince in one who treats her with deference as if she were a princess. Percival had an unconscious grace of bearing and attitude, and the considerable advantage of well-made clothes. Poverty had not yet reduced him to cheap coats and advertised trousers. And perhaps the crowning fascination in poor Lydia's eyes was the slight, dark, silky moustache which emphasized without hiding his lips.