полная версия

полная версияSix Lectures on Light. Delivered In The United States In 1872-1873

Soon after the publication of Kirchhoff's discovery, Professor Stokes, who also, ten years prior to the discovery, had nearly anticipated it, borrowed an illustration from sound, to explain the reciprocity of radiation and absorption. A stretched string responds to aërial vibrations which synchronize with its own. A great number of such strings stretched in space would roughly represent a medium; and if the note common to them all were sounded at a distance they would take up or absorb its vibrations.

When a violin-bow is drawn across this tuning-fork, the room is immediately filled with a musical sound, which may be regarded as the radiation or emission of sound from the fork. A few days ago, on sounding this fork, I noticed that when its vibrations were quenched, the sound seemed to be continued, though more feebly. It appeared, moreover, to come from under a distant table, where stood a number of tuning-forks of different sizes and rates of vibration. One of these, and one only, had been started by the sounding fork, and it was the one whose rate of vibration was the same as that of the fork which started it. This is an instance of the absorption of the sound of one fork by another. Placing two unisonant forks near each other, sweeping the bow over one of them, and then quenching the agitated fork, the other continues to sound; this other can re-excite the former, and several transfers of sound between the two forks can be thus effected. Placing a cent-piece on each prong of one of the forks, we destroy its perfect synchronism with the other, and no such communication of sound from the one to the other is then possible.

I have now to bring before you, on a suitable scale, the demonstration that we can do with light what has been here done with sound. For several days in 1861 I endeavoured to accomplish this, with only partial success. In iron dishes a mixture of dilute alcohol and salt was placed, and warmed so as to promote vaporization. The vapour was ignited, and through the yellow flame thus produced the beam from the electric lamp was sent; but a faint darkening only of the yellow band of a projected spectrum could be obtained. A trough was then made which, when fed with the salt and alcohol, yielded a flame ten feet thick; but the result of sending the light through this depth of flame was still unsatisfactory. Remembering that the direct combustion of sodium in a Bunsen's flame produces a yellow far more intense than that of the salt flame, and inferring that the intensity of the colour indicated the copiousness of the incandescent vapour, I sent through the flame from metallic sodium the beam of the electric lamp. The success was complete; and this experiment I wish now to repeat in your presence.25

Firstly then you notice, when a fragment of sodium is placed in a platinum spoon and introduced into a Bunsen's flame, an intensely yellow light is produced. It corresponds in refrangibility with the yellow band of the spectrum. Like our tuning-fork, it emits waves of a special period. When the white light from the electric lamp is sent through that flame, you will have ocular proof that the yellow flame intercepts the yellow of the spectrum; in other words, that it absorbs waves of the same period as its own, thus producing, to all intents and purposes, a dark Fraunhofer's band in the place of the yellow.

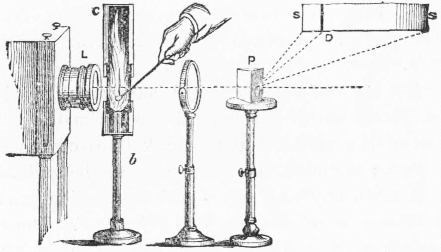

In front of the slit (at L, fig. 56) through which the beam issues is placed a Bunsen's burner (b) protected by a chimney (C). This beam, after passing through a lens, traverses the prism (P) (in the real experiment there was a pair of prisms), is there decomposed, and forms a vivid continuous spectrum (S S) upon the screen. Introducing a platinum spoon with its pellet of sodium into the Bunsen's flame, the pellet first fuses, colours the flame intensely yellow, and at length bursts into violent combustion. At the same moment the spectrum is furrowed by an intensely dark band (D), two inches wide and two feet long. Introducing and withdrawing the sodium flame in rapid succession, the sudden appearance and disappearance of the band of darkness is shown in a most striking manner. In contrast with the adjacent brightness this band appears absolutely black, so vigorous is the absorption. The blackness, however, is but relative, for upon the dark space falls a portion of the light of the sodium flame.

Fig. 56.

I have already referred to the experiment of Foucault; but other workers also had been engaged on the borders of this subject before it was taken up by Bunsen and Kirchhoff. With some modification I have on a former occasion used the following words regarding the precursors of the discovery of spectrum analysis, and solar chemistry:—'Mr. Talbot had observed the bright lines in the spectra of coloured flames, and both he and Sir John Herschel pointed out the possibility of making prismatic analysis a chemical test of exceeding delicacy, though not of entire certainty. More than a quarter of a century ago Dr. Miller gave drawings and descriptions of the spectra of various coloured flames. Wheatstone, with his accustomed acuteness, analyzed the light of the electric spark, and proved that the metals between which the spark passed determined the bright bands in its spectrum. In an investigation described by Kirchhoff as "classical," Swan had shown that 1/2,500,000 of a grain of sodium in a Bunsen's flame could be detected by its spectrum. He also proved the constancy of the bright lines in the spectra of hydrocarbon flames. Masson published a prize essay on the bands of the induction spark; while Van der Willigen, and more recently Plücker, have also given us beautiful drawings of spectra obtained from the same source.

'But none of these distinguished men betrayed the least knowledge of the connexion between the bright bands of the metals and the dark lines of the solar spectrum; nor could spectrum analysis be said to be placed upon anything like a safe foundation prior to the researches of Bunsen and Kirchhoff. The man who, in a published paper, came nearest to the philosophy of the subject was Ångström. In that paper, translated by myself, and published in the "Philosophical Magazine" for 1855, he indicates that the rays which a body absorbs are precisely those which, when luminous, it can emit. In another place, he speaks of one of his spectra giving the general impression of the reversal of the solar spectrum. But his memoir, philosophical as it is, is distinctly marked by the uncertainty of his time. Foucault, Thomson, and Balfour Stewart have all been near the discovery, while, as already stated, it was almost hit by the acute but unpublished conjecture of Stokes.'

Mentally, as well as physically, every year of the world's age is the outgrowth and offspring of all preceding years. Science proves itself to be a genuine product of Nature by growing according to this law. We have no solution of continuity here. All great discoveries are duly prepared for in two ways; first, by other discoveries which form their prelude; and, secondly, by the sharpening of the inquiring intellect. Thus Ptolemy grew out of Hipparchus, Copernicus out of both, Kepler out of all three, and Newton out of all the four. Newton did not rise suddenly from the sea-level of the intellect to his amazing elevation. At the time that he appeared, the table-land of knowledge was already high. He juts, it is true, above the table-land, as a massive peak; still he is supported by the plateau, and a great part of his absolute height is the height of humanity in his time. It is thus with the discoveries of Kirchhoff. Much had been previously accomplished; this he mastered, and then by the force of individual genius went beyond it. He replaced uncertainty by certainty, vagueness by definiteness, confusion by order; and I do not think that Newton has a surer claim to the discoveries that have made his name immortal, than Kirchhoff has to the credit of gathering up the fragmentary knowledge of his time, of vastly extending it, and of infusing into it the life of great principles.

With one additional point we will wind up our illustrations of the principles of solar chemistry. Owing to the scattering of light by matter floating mechanically in the earth's atmosphere, the sun is seen not sharply defined, but surrounded by a luminous glare. Now, a loud noise will drown a whisper, an intense light will overpower a feeble one, and so this circumsolar glare prevents us from seeing many striking appearances round the border of the sun. The glare is abolished in total eclipses, when the moon comes between the earth and the sun, and there are then seen a series of rose-coloured protuberances, stretching sometimes tens of thousands of miles beyond the dark edge of the moon. They are described by Vassenius in the 'Philosophical Transactions' for 1733; and were probably observed even earlier than this. In 1842 they attracted great attention, and were then compared to Alpine snow-peaks reddened by the evening sun. That these prominences are flaming gas, and principally hydrogen gas, was first proved by M. Janssen during an eclipse observed in India, on the 18th of August, 1868.

But the prominences may be rendered visible in sunshine; and for a reason easily understood. You have seen in these lectures a single prism employed to produce a spectrum, and you have seen a pair of prisms employed. In the latter case, the dispersed white light, being diffused over about twice the area, had all its colours proportionately diluted. You have also seen one prism and a pair of prisms employed to produce the bands of incandescent vapours; but here the light of each band, being absolutely monochromatic, was incapable of further dispersion by the second prism, and could not therefore be weakened by such dispersion.

Apply these considerations to the circumsolar region. The glare of white light round the sun can be dispersed and weakened to any extent, by augmenting the number of prisms; while a monochromatic light, mixed with this glare, and masked by it, would retain its intensity unenfeebled by dispersion. Upon this consideration has been founded a method of observation, applied independently by M. Janssen in India and by Mr. Lockyer in England, by which the monochromatic bands of the prominences are caused to obtain the mastery, and to appear in broad daylight. By searching carefully and skilfully round the sun's rim, Mr. Lockyer has proved these prominences to be mere local juttings from a fiery envelope which entirely clasps the sun, and which he has called the Chromosphere.

It would lead us far beyond the object of these lectures to dwell upon the numerous interesting and important results obtained by Secchi, Respighi, Young, and other distinguished men who have worked at the chemistry of the sun and its appendages. Nor can I do more at present than make a passing reference to the excellent labours of Dr. Huggins in connexion with the fixed stars, nebulae, and comets. They, more than any others, illustrate the literal truth of the statement, that the establishment of spectrum analysis, and the explanation of Fraunhofer's lines, carried with them an immeasurable extension of the chemist's range. The truly powerful experiments of Professor Dewar are daily adding to our knowledge, while the refined researches of Capt. Abney and others are opening new fields of inquiry. But my object here is to make principles plain, rather than to follow out the details of their illustration.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

My desire in these lectures has been to show you, with as little breach of continuity as possible, something of the past growth and present aspect of a department of science, in which have laboured some of the greatest intellects the world has ever seen. I have sought to confer upon each experiment a distinct intellectual value, for experiments ought to be the representatives and expositors of thought—a language addressed to the eye as spoken words are to the ear. In association with its context, nothing is more impressive or instructive than a fit experiment; but, apart from its context, it rather suits the conjurer's purpose of surprise, than the purpose of education which ought to be the ruling motive of the scientific man.

And now a brief summary of our work will not be out of place. Our present mastery over the laws and phenomena of light has its origin in the desire of man to know. We have seen the ancients busy with this problem, but, like a child who uses his arms aimlessly, for want of the necessary muscular training, so these early men speculated vaguely and confusedly regarding natural phenomena, not having had the discipline needed to give clearness to their insight, and firmness to their grasp of principles. They assured themselves of the rectilineal propagation of light, and that the angle of incidence was equal to the angle of reflection. For more than a thousand years—I might say, indeed, for more than fifteen hundred years—the scientific intellect appears as if smitten with paralysis, the fact being that, during this time, the mental force, which might have run in the direction of science, was diverted into other directions.

The course of investigation, as regards light, was resumed in 1100 by an Arabian philosopher named Alhazen. Then it was taken up in succession by Roger Bacon, Vitellio, and Kepler. These men, though failing to detect the principles which ruled the facts, kept the fire of investigation constantly burning. Then came the fundamental discovery of Snell, that cornerstone of optics, as I have already called it, and immediately afterwards we have the application, by Descartes, of Snell's discovery to the explanation of the rainbow. Following this we have the overthrow, by Roemer, of the notion of Descartes, that light was transmitted instantaneously through space. Then came Newton's crowning experiments on the analysis and synthesis of white light, by which it was proved to be compounded of various kinds of light of different degrees of refrangibility.

Up to his demonstration of the composition of white light, Newton had been everywhere triumphant—triumphant in the heavens, triumphant on the earth, and his subsequent experimental work is, for the most part, of immortal value. But infallibility is not an attribute of man, and, soon after his discovery of the nature of white light, Newton proved himself human. He supposed that refraction and chromatic dispersion went hand in hand, and that you could not abolish the one without at the same time abolishing the other. Here Dollond corrected him.

But Newton committed a graver error than this. Science, as I sought to make clear to you in our second lecture, is only in part a thing of the senses. The roots of phenomena are embedded in a region beyond the reach of the senses, and less than the root of the matter will never satisfy the scientific mind. We find, accordingly, in this career of optics the greatest minds constantly yearning to break the bounds of the senses, and to trace phenomena to their subsensible foundation. Thus impelled, they entered the region of theory, and here Newton, though drawn from time to time towards truth, was drawn still more strongly towards error; and he made error his substantial choice. His experiments are imperishable, but his theory has passed away. For a century it stood like a dam across the course of discovery; but, as with all barriers that rest upon authority, and not upon truth, the pressure from behind increased, and eventually swept the barrier away.

In 1808 Malus, looking through Iceland spar at the sun, reflected from the window of the Luxembourg Palace in Paris, discovered the polarization of light by reflection. As stated at the time, this discovery ushered in the darkest hour in the fortunes of the wave theory. But the darkness did not continue. In 1811 Arago discovered the splendid chromatic phenomena which we have had illustrated by the deportment of plates of gypsum in polarized light; he also discovered the rotation of the plane of polarization by quartz-crystals. In 1813 Seebeck discovered the polarization of light by tourmaline. That same year Brewster discovered those magnificent bands of colour that surround the axes of biaxal crystals. In 1814 Wollaston discovered the rings of Iceland spar. All these effects, which, without a theoretic clue, would leave the human mind in a jungle of phenomena without harmony or relation, were organically connected by the theory of undulation.

The wave theory was applied and verified in all directions, Airy being especially conspicuous for the severity and conclusiveness of his proofs. A most remarkable verification fell to the lot of the late Sir William Hamilton, of Dublin, who, taking up the theory where Fresnel had left it, arrived at the conclusion that at four special points of the 'wave-surface' in double-refracting crystals, the ray was divided, not into two parts but into an infinite number of parts; forming at these points a continuous conical envelope instead of two images. No human eye had ever seen this envelope when Sir William Hamilton inferred its existence. He asked Dr. Lloyd to test experimentally the truth of his theoretic conclusion. Lloyd, taking a crystal of arragonite, and following with the most scrupulous exactness the indications of theory, cutting the crystal where theory said it ought to be cut, observing it where theory said it ought to be observed, discovered the luminous envelope which had previously been a mere idea in the mind of the mathematician.

Nevertheless this great theory of undulation, like many another truth, which in the long run has proved a blessing to humanity, had to establish, by hot conflict, its right to existence. Illustrious names were arrayed against it. It had been enunciated by Hooke, it had been expounded and applied by Huyghens, it had been defended by Euler. But they made no impression. And, indeed, the theory in their hands lacked the strength of a demonstration. It first took the form of a demonstrated verity in the hands of Thomas Young. He brought the waves of light to bear upon each other, causing them to support each other, and to extinguish each other at will. From their mutual actions he determined their lengths, and applied his knowledge in all directions. He finally showed that the difficulty of polarization yielded to the grasp of theory.

After him came Fresnel, whose transcendent mathematical abilities enabled him to give the theory a generality unattained by Young. He seized it in its entirety; followed the ether into the hearts of crystals of the most complicated structure, and into bodies subjected to strain and pressure. He showed that the facts discovered by Malus, Arago, Brewster, and Biot were so many ganglia, so to speak, of his theoretic organism, deriving from it sustenance and explanation. With a mind too strong for the body with which it was associated, that body became a wreck long before it had become old, and Fresnel died, leaving, however, behind him a name immortal in the annals of science.

One word more I should like to say regarding Fresnel. There are things better even than science. Character is higher than Intellect, but it is especially pleasant to those who wish to think well of human nature when high intellect and upright character are found combined. They were combined in this young Frenchman. In those hot conflicts of the undulatory theory, he stood forth as a man of integrity, claiming no more than his right, and ready to concede their rights to others. He at once recognized and acknowledged the merits of Thomas Young. Indeed, it was he, and his fellow-countryman Arago, who first startled England into the consciousness of the injustice done to Young in the 'Edinburgh Review.'

I should like to read to you a brief extract from a letter written by Fresnel to Young in 1824, as it throws a pleasant light upon the character of the French philosopher. 'For a long time,' says Fresnel, 'that sensibility, or that vanity, which people call love of glory has been much blunted in me. I labour much less to catch the suffrages of the public, than to obtain that inward approval which has always been the sweetest reward of my efforts. Without doubt, in moments of disgust and discouragement, I have often needed the spur of vanity to excite me to pursue my researches. But all the compliments I have received from Arago, De la Place, and Biot never gave me so much pleasure as the discovery of a theoretic truth or the confirmation of a calculation by experiment.'

This, then, is the core of the whole matter as regards science. It must be cultivated for its own sake, for the pure love of truth, rather than for the applause or profit that it brings. And now my occupation in America is well-nigh gone. Still I will bespeak your tolerance for a few concluding remarks, in reference to the men who have bequeathed to us the vast body of knowledge of which I have sought to give you some faint idea in these lectures. What was the motive that spurred them on? What urged them to those battles and those victories over reticent Nature, which have become the heritage of the human race? It is never to be forgotten that not one of those great investigators, from Aristotle down to Stokes and Kirchhoff, had any practical end in view, according to the ordinary definition of the word 'practical.' They did not propose to themselves money as an end, and knowledge as a means of obtaining it. For the most part, they nobly reversed this process, made knowledge their end, and such money as they possessed the means of obtaining it.

We see to-day the issues of their work in a thousand practical forms, and this may be thought sufficient to justify, if not ennoble, their efforts. But they did not work for such issues; their reward was of a totally different kind. In what way different? We love clothes, we love luxuries, we love fine equipages, we love money, and any man who can point to these as the result of his efforts in life, justifies these results before all the world. In America and England, more especially, he is a 'practical' man. But I would appeal confidently to this assembly whether such things exhaust the demands of human nature? The very presence here for six inclement nights of this great audience, embodying so much of the mental force and refinement of this vast city,26 is an answer to my question. I need not tell such an assembly that there are joys of the intellect as well as joys of the body, or that these pleasures of the spirit constituted the reward of our great investigators. Led on by the whisperings of natural truth, through pain and self-denial, they often pursued their work. With the ruling passion strong in death, some of them, when no longer able to hold a pen, dictated to their friends the last results of their labours, and then rested from them for ever.

Could we have seen these men at work, without any knowledge of the consequences of their work, what should we have thought of them? To the uninitiated, in their day, they might often appear as big children playing with soap-bubbles and other trifles. It is so to this hour. Could you watch the true investigator—your Henry or your Draper, for example—in his laboratory, unless animated by his spirit, you could hardly understand what keeps him there. Many of the objects which rivet his attention might appear to you utterly trivial; and if you were to ask him what is the use of his work, the chances are that you would confound him. He might not be able to express the use of it in intelligible terms. He might not be able to assure you that it will put a dollar into the pocket of any human being present or to come. That scientific discovery may put not only dollars into the pockets of individuals, but millions into the exchequers of nations, the history of science amply proves; but the hope of its doing so never was, and it never can be, the motive power of the investigator.

I know that some risk is run in speaking thus before practical men. I know what De Tocqueville says of you. 'The man of the North,' he says, 'has not only experience, but knowledge. He, however, does not care for science as a pleasure, and only embraces it with avidity when it leads to useful applications.' But what, I would ask, are the hopes of useful applications which have caused you so many times to fill this place, in spite of snow-drifts and biting cold? What, I may ask, is the origin of that kindness which drew me from my work in London to address you here, and which, if I permitted it, would send me home a millionaire? Not because I had taught you to make a single cent by science am I here to-night, but because I tried to the best of my ability to present science to the world as an intellectual good. Surely no two terms were ever so distorted and misapplied with reference to man, in his higher relations, as these terms useful and practical. Let us expand our definitions until they embrace all the needs of man, his highest intellectual needs inclusive. It is specially on this ground of its administering to the higher needs of the intellect; it is mainly because I believe it to be wholesome, not only as a source of knowledge but as a means of discipline, that I urge the claims of science upon your attention.