Полная версия

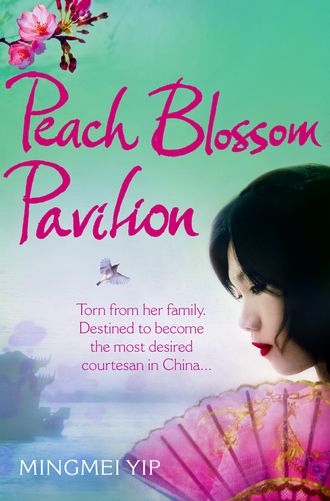

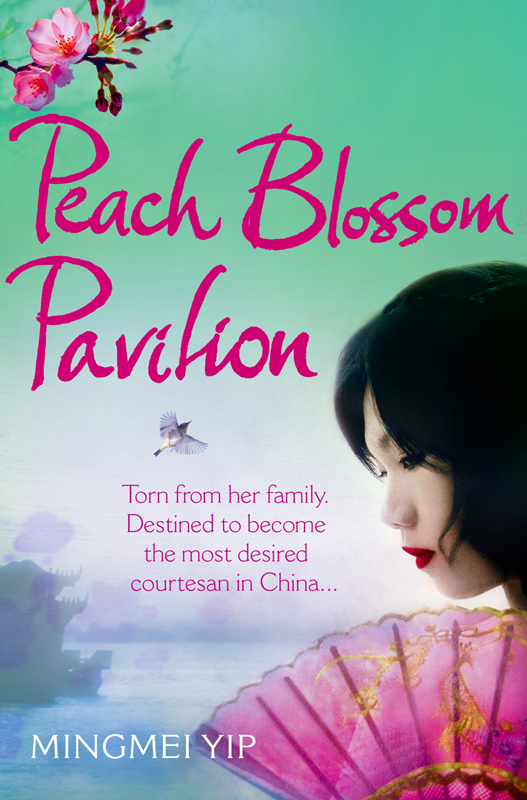

Peach Blossom Pavilion

Peach Blossom Pavilion

Mingmei Yip

Copyright

Avon

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Mingmei Yip 2008

Cover photographs © Natalia Campbell / Getty Images (woman); myu-myu / Getty Images (bird); Shutterstock.com; Kevin Hua Long Jiang / Getty Images (background).

Mingmei Yip asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007570126

Ebook Edition © February 2014 ISBN: 9780007570133

Version: 2014-07-25

Dedication

For Geoffrey, Who gives me both the fish and the bear’s paw.

When there is action above and compliance below, this is called the natural order of things.

When the man thrusts from above and the woman receives from below, this is called the balance between heaven and earth.

–Dong Xuanzi (Tang dynasty, AD 618–907)

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One

1. The Turquoise Pavilion

2. The North Station

3. The Dark Room

4. The Elegant Gathering

5. Spring Moon

6. A Lucky Day

7. The Jade Stalk and the Golden Gate

8. The Haunted Garden

9. The Art of Pleasing

10. The Longevity Wrinkles

11. Rape of the Rock

12. Beat the Cat

Part Two

13. Life Went On

14. Mr. Anderson

15. The Prestigious Prostitute

16. Red Jade

17. The Ways Out

18. The Jade Stalk Refuses to Salute

19. Last Journey in the Red Dust

Part Three

20. Chinese Soap Opera

21. Melting the Ice

22. American Handsome

23. The Escape

24. The Bandits

25. This Woman Is Not My Husband

26. The Monk and the Prostitute

27. The Encounter

28. Separation

29. Replaying the Pipa

30. Flight to Heaven

31. The Reunion

32. Back to Shanghai

33. Revenge

Part Four

34. Ginseng Tea

35. Back to Peking

36. The Nun and the Prostitute

37. An Unexpected Visitor

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Prologue

Precious Orchid

The California sun slowly streams in through my apartment window, then gropes its way past a bamboo plant, a Chinese vase spilling with plum blossoms, a small incense burner, then finally lands on Bao Lan – Precious Orchid – the woman lying opposite me without a stitch on.

Envy stabs my heart. I stare at her body as it curves in and out like a snake ready for mischief. She lies on a red silk sheet embroidered with flowers in gold thread. ‘Flower of the evil sea’ – this was what people in old Shanghai would whisper through cupped mouths. While now, in San Francisco, I murmur her name, ‘Bao Lan,’ sweetly as if savouring a candy in my mouth. I imagine inhaling the decadent fragrance from her sun-warmed nudity.

Bao Lan’s eyes shine big and her lips – full, sensuous, and painted a dark crimson – evoke in my mind the colour of rose petals in a fading dream. Petals that, when curled into a seductive smile, also whisper words of flattery. These, together with her smooth arm, raised and bent behind her head in a graceful curve, remind me of the Chinese saying ‘A pair of jade arms used as pillows to sleep on by a thousand guests; two slices of crimson lips tasted by ten thousand men.’

Now the rosy lips seem to say, ‘Please come to me.’

I nod, reaching my hand to touch the nimbus of black hair tumbling down her small, round breasts. Breasts the texture of silk and the colour of white jade. Breasts that were touched by many – soldiers, merchants, officials, scholars, artists, policemen, gangsters, a Catholic priest, a Taoist monk.

Feeling guilty of sacrilege, I withdraw my nearly century-old spotty and wrinkled hand. I keep rocking on my chair and watching Bao Lan as she continues to eye me silently. ‘Hai, how time flies like an arrow, and the sun and moon move back and forth like a shuttle!’ I recite the old saying, then carefully sip my ginseng tea.

‘Ahpo, it’s best-quality ginseng to keep your longevity and health,’ my great-granddaughter told me the other day when she brought the herb.

Last week, I celebrated my ninety-eighth birthday, and although they never say it out loud, I know they want my memoir to be finished before I board the immortal’s journey. When I say ‘they,’ I mean my great-granddaughter Jade Treasure and her American fiancé Leo Stanley. In a while, they will be coming to see me and begin recording my oral history.

Oral history! Do they forget that I can read and write? They treat me as if I were a dusty museum piece. They act like they’re doing me a great favour by digging me out from deep underground and bringing me to light. How can they forget that I am not only literate, but also well versed in all the arts – literature, music, painting, calligraphy, and poetry – and that’s exactly the reason they want to write about me?

Now Bao Lan seems to say, ‘Old woman, please go away! Why do you always have to remind me how old you are and how accomplished you were?! Can’t you leave me alone to enjoy myself at the height of my youth and beauty?’

‘Sure,’ I mutter to the air, feeling the wrinkles weighing around the corners of my mouth.

But she keeps staring silently at me with eyes which resemble two graceful dots of ink on rice paper. She’s strange, this woman who shares the same house with me but only communicates with the brightness of her eyes and the sensuousness of her body.

I am used to her eccentricity, because she’s my other – much wilder and younger – self! The delicate beauty opposite me is but a faded oil painting done seventy-five years ago when I was twenty-three.

And the last poet-musician courtesan in Shanghai.

That’s why they keep pushing me to tell, or sell, my story – I am the carrier of a mysterious cultural phenomenon – ming ji.

The prestigious prostitute. Prestigious prostitute? Yes, that was what we were called in old China. A species as extinct as the Chinese emperors, after China became a republic. Some say it’s a tragic loss; others argue: how can the disappearance of prostitutes be tragic?

The cordless phone trills on the coffee table; I pick it up with my stiff, arthritic hand. Jane and Leo are already downstairs. Jane is Jade Treasure’s English name, of which I disapprove because it sounds so much like the word ‘pan fry’ in Chinese. When I call her ‘Jane, Jane,’ I can almost smell fish cooking in sizzling oil – Sizzz! Sizzz! It sounds as if I’d cook my own flesh and blood!

Now the two young people burst into my nursing home apartment with their laughter and overflowing energy, their embarrassingly long limbs flailing in all directions. Jade Treasure flounces up to peck my cheek, swinging a basket of fruit in front of me, making me dizzy.

‘Hi, Grandmama, you look good today! The ginseng gives you good qi?’

‘Jade, can you show some respect to an old woman who has witnessed, literally, the ups and downs of a century?’ I say, pushing away the basket of fruit.

‘Grandmama!’ Jade mock protests, then dumps the basket on the table with a clank and plops down on the sofa next to me.

It is now Leo’s turn to peck my cheek, then he says in his smooth Mandarin, ‘How are you today, Popo?’

This American boy calls me Popo, the respectful way of addressing an elderly lady in Chinese, while my Jade Treasure prefers the more Westernised Grandmama (she adds another ‘ma’ for ‘great’ grandmother). Although I am always suspicious of laofan, old barbarians, I kind of like Leo. He’s a nice boy, good-looking with a big body and soft blonde hair, a graduate of journalism at a very good university called Ge-lin-bi-ya? (so I was told by Jade), speaks very good Mandarin, now works as an editor for a very famous publisher called Ah-ba Call-lings? (so I was also told by Jade). And madly in love with my Jade Treasure.

Jade is already clanking bowls and plates in my small kitchen, preparing snacks. Her bare legs play hide and seek behind the half-opened door, while her excessive energy thrusts her to and fro between the refrigerator, the cupboard, the sink, the stove.

A half hour later, after we’ve finished our snacks and the trays are put away and the table cleaned, Leo and Jade sit down beside me on the sofa, carefully taking out their recorder, pads, pens. Faces glowing with excitement, they look like Chinese students eager to please their teacher. It touches me to see their expressions turn serious as if they were burdened by the sacred responsibility of saving a precious heritage from sinking into quicksand.

‘Grandmama,’ Jade says after she’s discussed it in English with her fiancé, ‘Leo and I agreed that it’s best for you to start your story from the beginning. That is, when you were sold to the turquoise pavilion after Great-great-grandpapa was executed.’

I’m glad she is discreet enough not to say jiyuan, prostitution house, or worse, jixiang, whorehouse, but instead uses the much more refined and poetic qinglou – turquoise pavilion.

‘Jade, if you’re so interested in Chinese culture, do you know there are more than forty words for prostitution house … fire pit; tender village; brocade gate; wind and moon domain—’

Jade interrupts. ‘Grandmama, so which were you in?’

‘You know, we had our own hierarchy. The prestigious book chamber ladies,’ I tilt my head, ‘like myself, condescended to the second-rate long gown ladies, and they in turn snubbed those who worked in the second hall. And of course, everyone would spit on the homeless wild chickens as if they were nonhuman.’

‘Wow! Cool stuff!’ Jade exclaims, then exchanges whispers with Leo. She turns back to stare at me, her elongated eyes sparkling with enthusiasm. ‘Grandmama, we think that it’s better if you can use the “talk story” style. Besides, can you add even more juicy stuff?’

‘No.’ I wave them a dismissive hand. ‘Do you think my life is not miserable enough to be saleable? This is my story, and I’ll do it my way!’

‘Yes, of course!’ The two heads nod like basketballs under thumping hands.

‘All right, my big prince and princess, what else?’

‘That’s all, Grandmama. Let’s start!’ The two young faces gleam as if they were about to watch a Hollywood soap opera – forgetting that I have told them a hundred times that my life is even a thousand times soapier.

1

The Turquoise Pavilion

To be a prostitute was my fate.

After all, no murderer’s daughter would be accepted into a decent household to be a wife whose children would be smeared with crime even before they were born. The only other choice was my mother’s – to take refuge as a nun, for the only other society which would accept a criminal’s relatives lay within the empty gate.

I had just turned thirteen when I exchanged the quiet life of a family for the tumult of a prostitution house. But not like the others, whose parents had been too poor to feed them, or who had been kidnapped and sold by bandits.

It all happened because my father was convicted of a crime – one he’d never committed.

‘That was the mistake your father should never have made,’ my mother told me over and over, ‘trying to be righteous, and,’ she added bitterly, ‘meddling in rich men’s business.’

True. For that ‘business’ cost him his own life, and fatefully changed the life of his wife and daughter.

Baba had been a Peking opera performer and a musician. Trained as a martial arts actor, he played acrobats and warriors. During one performance, while fighting with four pennants strapped to his thirty-pound suit of armour, he jumped down from four stacked chairs in his high-soled boots and broke his leg. Unable to perform on stage anymore, he played the two-stringed fiddle in the troupe’s orchestra. After several years, he became even more famous for his fiddle playing, and an amateur Peking opera group led by the wife of a Shanghai warlord hired him as its accompanist. Every month the wife would hold a big party in the house’s lavish garden. It was an incident in that garden that completely changed our family’s destiny.

One moonlit evening amid the cheerful tunes of the fiddle and the falsetto voices of the silk-clad and heavily jewelled tai tai – society ladies – the drunken warlord raped his own teenage daughter.

The girl grabbed her father’s gun and fled to the garden where the guests were gathered. The warlord ran behind her, puffing and pants falling. Suddenly his daughter stopped and turned to him. Tears streaming down her cheeks, she slowly pointed the gun to her head. ‘Beast! If you dare come an inch closer, I’ll shoot myself!’

Baba threw down his precious fiddle and ran to the source of the tumult. He pushed away the gaping guests, leaped forward, and tried to seize the gun. But it went off. The hapless girl fell dead to the ground in a pool of blood surrounded by the stunned guests and servants.

The warlord turned to grab Baba’s throat till his tongue protruded. Eyes blurred and face as red as his daughter’s splattered blood, he spat on Baba. ‘Animal! You raped my daughter and killed her!’

Although all the members in the household knew it was a false accusation, nobody was willing to right the wrong. The servants were scared and powerless. The rich guests couldn’t have cared less.

One general meditatively stroked his beard, sneering, ‘Big deal, it’s just a fiddle player.’ And that ended the whole event.

Indeed, it was a big deal for us. For Baba was executed. Mother took refuge as a Buddhist nun in a temple in Peking. I was taken away to a prostitution house.

This all happened in 1918.

Thereafter, during the tender years of my youth, while my mother was strenuously cultivating desirelessness in the Pure Lotus Nunnery in Peking, I was busy stirring up desire within the Peach Blossom Pavilion.

That was the mistake your father should never have made – trying to be righteous and meddling in rich men’s business.

Mother’s saying kept knocking around in my head until one day I swore, kneeling before Guan Yin – the Goddess of Mercy – that I would never be merciful in this life. But not meddle in rich men’s business? It was precisely the rich and powerful at whom I aimed my arts of pleasing. Like Guan Yin with a thousand arms holding a thousand amulets to charm, I was determined to cultivate myself to be a woman with a thousand scheming hearts to lure a thousand men into my arms.

But, of course, this kind of cultivation started later, when I had become aware of the realm of the wind and moon. When I’d first entered the prostitution house, I was but a little girl with a heart split into two: one half light with innocence, the other heavy with sorrow.

In the prostitution house, I was given the name Precious Orchid. It was only my professional name; my real name was Xiang Xiang, given for two reasons. I was born with a natural xiang – body fragrance (a mingling of fresh milk, honey, and jasmine), something which rarely happens except in legends where the protagonist lives on nothing but flowers and herbs. Second, I was named after the Xiang River of Hunan Province. My parents, who had given me this name, had cherished the hope that my life would be as nurturing as the waterway of my ancestors, while never expecting that it was my overflowing tears which would nurture the river as it flows its never-ending course. They had also hoped that my life would sing with happiness like the cheerful river, never imagining that what flowed in my voice was nothing but the bittersweet melodies of Karma.

Despite our abject poverty after Baba’s death, it was never my mother’s intent to sell me into Peach Blossom Pavilion. This bit of chicanery was the work of one of her distant relatives, a woman by the name of Fang Rong – Beautiful Countenance. Mother had met her only once, during a Chinese New Year’s gathering at a distant uncle’s house. Not long after Baba had been executed, Fang Rong appeared one day out of nowhere and told my mother that she could take good care of me. When I first laid eyes on her, I was surprised that she didn’t look at all like what her name implied. Instead, she had the body of a stuffed rice bag, the face of a basin, and the eyes of a rat, above which a big mole moved menacingly.

Fang Rong claimed that she worked as a housekeeper for a rich family. The master, a merchant of foreign trade, was looking for a young girl with a quick mind and swift hands to help in the household. The matter was decided without hesitation. Mother, completely forgetting her vow never to be involved in rich men’s business, was relieved that I’d have a roof over my head. So, with her departure for Peking looming, she agreed to let Fang Rong take me away.

Both Mother and Fang Rong looked happy chatting under the sparkling sun. Toward the end of their conversation, after Fang Rong had given Mother the address of the ‘rich businessman,’ she shoved me into a waiting rickshaw. ‘Quick! Don’t make the master wait!’

When the vehicle was about to take off, Mother put her face close to me and whispered, ‘From now on, listen to Aunty Fang and your new master and behave. Will you promise me that?’

I nodded, noticing the tears welling in her eyes. She gently laid the cloth sack containing my meagre possessions (a small amount of cash and a few rice balls sprinkled with bits of salted fish) on my lap, then put her hand on my head. ‘Xiang Xiang, I’ll be leaving in a month. If I can, I’ll visit you. But if I don’t, I’ll write as soon as I’ve arrived in Peking.’ She paused, a faint smile breaking on her withered face. ‘You’re lucky …’

I touched her hand. ‘Ma …’

Just as I was struggling to say something, Fang Rong’s voice jolted us apart. ‘All right, let’s go, better not be late.’ With that, the rickshaw puller lifted the poles and we started to move.

I turned back and waved to Mother until she became a small dot and finally vanished like the last morning dew.

Fang Rong rode beside me in silence. Houses floated by as the rickshaw puller grunted along. After twists and turns through endless avenues and back alleys, the rickshaw entered a tree-lined boulevard.

Fang Rong turned to me and smiled. ‘Xiang Xiang, we’ll soon be there.’

Though the air was nippy, the coolie was sweating profusely. We bumped along a crowded street past a tailor, an embroidery shop, a hair salon, and a shoe store before the coolie finally grunted to a stop.

Fang Rong paid and we got out in front of the most beautiful mansion I’d ever seen. With walls painted a pale pink, the building rose tall and imposing, with a tightly closed red iron gate fiercely guarded by two stone lions. At the entrance, a solitary red lantern swayed gently in the breeze. An ornate wooden sign above the lintel glinted in the afternoon sun. I shaded my eyes and saw a shiny signboard, black with three large gold characters: PEACH BLOSSOM PAVILION. On either side, vertical boards flanking the gate read:

Guests flocking to the pavilion like birds,

Beauties blooming in the garden like flowers.

‘Aunty Fang,’ I pointed to the sign, ‘what is this Peach—’

‘Come on,’ Fang Rong cast me an annoyed look, ‘don’t let your father wait,’ and pulled me along.

My father? Didn’t she know that he was already dead? Just as I was wondering what this was all about, the gate creaked open, revealing a man of about forty; underneath shiny hair parted in the middle shone a smooth, handsome face. An embroidered silk jacket was draped elegantly over a lean, sinewy body.

He scrutinised me for long moments, then his face broke into a pleasant grin. ‘Ah, so the rumour is true. What a lovely girl!’ His slender fingers with their long, immaculate nails reached to pat my head. I felt an instant liking for this man my father’s age. I also wondered, how could the ugly-to-death Fang Rong catch such a nice-looking man?

‘Wu Qiang,’ Fang Rong drew away his hand, ‘haven’t you ever seen a pretty girl in your life?’ Then she turned to me. ‘This is my husband Wu Qiang and your father.’

‘But Aunty—’

Now Fang Rong put on an ear-reaching grin. ‘Xiang Xiang, your father is dead, so from now on Wu Qiang is your father. Call him De.’

Despite my liking for this man, in my heart no one could take the place of my father. ‘But he’s not my de!’

Fang Rong shot me a smile with the skin, but not the flesh. ‘I’ve told you that now he is, and I’m your mother, so call me Mama.’

Before I could protest again, she’d already half-pushed me along through a narrow entranceway. Then I forgot to complain because as we passed into the courtyard, my eyes beheld another world. Enclosed within the red fence was a garden where lush flowerbeds gave off a pleasing aroma. On the walls were painted lovely maidens cavorting among exotic flowers. A fountain murmured, spurting in willowy arcs. In a pond, golden carps swished their tails and gurgled trails of bubbles. A stone bridge led across the pond to a pavilion with gracefully upturned eaves. Patches of soothing shade were cast by artfully placed bamboo groves.

While hurrying after Fang Rong and Wu Qiang, I spotted a small face peeking out at me from behind the bamboo grove. What struck me was not her face but the sad, watery eyes which gazed into mine, as if desperate to tell a tale.

When I was on the verge of asking about her, Fang Rong cast me a tentative glance. ‘Xiang Xiang, aren’t you happy that this is now your new home? Isn’t it much better than your old one?’

I nodded emphatically, while feeling stung by those sad eyes.

‘I’m sure you’ll like it even better when you taste the wonderful food cooked by our chef,’ Wu Qiang chimed in enthusiastically.