полная версия

полная версияHarper's Young People, November 18, 1879

Oh, if you never played Robinson Crusoe, you can't think what fun we had playing it, and we played almost the whole book through, sometimes one part, and sometimes another, and whatever part we played, Billy tried to have it just as near like what the book said as it could be made without a real ship, a real ocean, and a real island; and he was so in earnest that it seemed real to me, and I used to feel shivery and scared when he cried out that the savages were coming.

There were all sorts of nice rubbishy things in the cellar to play with, 'cause everything that got broken or too old for use in the house—or "the wreck," as Billy called it—got thrown out into the old cellar: empty fruit cans, broken dishes, leaky old pans and dippers, parts of broken chairs and broken looking-glasses, and old kettles and frying-pans; bits of shingles, old nails, and piles and piles of clam and oyster shells; and Billy knew the minute he saw a thing what to do with it.

Kate and I helped with pieces of muslin, ribbon, and old calico, so that every day the little square place behind the chimney was more and more like Robinson Crusoe's own house on the real island.

One day papa stopped and looked at us as he was going by, and said he was afraid it wasn't a safe place for us, the old chimney might tumble down on us, or we might cut our feet on some of the broken things; but mother only smiled and said, "Oh, do let the children be happy." I guess she was jolly to play with when she was a little girl.

She often came out, or sent Biddy out with a nice turn-over, or a plate of hot ginger cookies; and after papa spoke about the chimney, she climbed down into the cellar, and went over and felt the chimney all round to see if it was quite firm. Once we coaxed her to stay with us during the two weeks while the savages were on the island. Billy, who liked to play just what was in the book, said at first that Robinson Crusoe didn't ever have his mother with him, but he "guessed the man who wrote the story would have put that in if he had known what larks it was."

But one day something happened that stopped our playing Robinson Crusoe or anything else for a long time. Mother had sent Billy on an errand a long way off, Kate Ames was sick, and Teddy had to stay at home to amuse her, and I was in the house, in the sitting-room with mother.

The morning had been very pleasant and warm, and though I wished we were all together in the cellar at play, I was quite contented with a book called Beechnut, a Franconia story, and I was thinking that Beechnut was almost just like Billy. Mother laid down her sewing, and went out of the room, patting my cheek with her kind hand as she passed, to tell Biddy something about dinner.

In a few minutes it grew so dark that I looked out of the window to see what made it, and saw the sky covering with a big black cloud that unrolled ever so fast, and the wind began to blow very hard, and the trees bent and turned over the white sides of their leaves in it. If Billy had been at home I should have gone out with him to run in the wind, because it feels so pleasant on my cheeks and in my hair, just as flowing water looks. It grew darker, began to rain, and the wind grew louder, with a queer sound; but I could see to read, and I got so interested in Beechnut that, though I saw out of the side of my eye some one go by the window, I did not really think about it, but kept on reading till I heard papa's voice in the next room, and heard mamma say:

"I'm so glad you're safe in the house; but where can Billy be? I sent him to Morton's, but he ought to have been home an hour ago. It's a perfect hurricane!"

"Oh, he'll do," said papa; "he's under cover somewhere, but—"

I couldn't hear any more, for just then the windows rattled; the floor shook so I could hardly keep my seat. There was an awful roar of wind, a crackling sound in the walls, a crash outside as if a load of coal were being tumbled into the bin, and the pretty vases on the mantel fell and broke to pieces on the floor. I ran as well as I could, and caught hold of papa. He held mamma's hands. She was white, and looked so strange. It frightened me more than all the rest, and I couldn't keep from crying.

"Hurricane! my dear," I heard papa say; "it's an earthquake shock. I do wish we knew where Billy is."

Then I remembered, and I said, "Oh, mamma, don't be frightened; Billy came in half an hour ago."

But when papa, mamma, and I—Biddy coming after us, with her apron up over her face, and crying, "Och, what a nize!" and "God save us!" every step—went from room to room, we didn't find Billy.

"Maggie, are you sure you saw him?" said mamma, stopping me, with both her hands on my shoulders, at the head of the stairs—"are you sure?"

"Oh yes; he went by the window when I was reading in Beechnut about where Phonny—"

"The cellar!" cried mamma, and drew in her breath just like the sound of the wind.

Already the clouds had rolled away; the storm was over; and Biddy, who had been standing at the back stairway window, cried out, "Feth, mem, an' av me two eyes don't be afther desavin' me, the owld chimbley's blowed over, an' niver a brick lift o' the poor childer's foine play-house."

In a moment mamma was down the stairs; papa could not hold her nor catch up with her, and we all ran after her to the edge of the cellar. Our pretty Robinson Crusoe house was all ruined. Dirt, sticks, stones, and everything that had lain about the yard were just as if they had been swept with a big broom into the cellar; and the big chimney—all blown to pieces now—helped to fill up the cave.

Mother was crying dreadfully, and I cried too. She went right down on her knees, and began picking up and throwing out the bricks. Papa could not stop her; she only said, in a voice that did not sound like mamma's voice at all, "My Billy's here."

It was so dreadful I can't remember exactly all about it; but papa got Mr. Ames and one or two other men, and after a while mamma caught hold of and kissed a little coat sleeve, and a hand so white it didn't look one bit like Billy's. Mamma thought Billy was dead, and she sat down very still, and did not try to work any more, but held the hand until the men had lifted every bit off from Billy; and she went beside them when he was carried in. He was not dead, he was only stunned; but his arm, the one mamma found, was broken in three places. He had a great deal of pain before his arm began to heal; but he never made a bit of fuss about it, and he never said anything to papa or mamma about the cellar, and how it happened, except just once when mamma asked him a question, and he told her he had gone into the cellar to cover up some of the things if he could. But the first time we were left alone together he called me close to him.

"The cave's all spoiled, I s'pose?" said he.

"Oh yes. Papa had it filled up right away."

Billy didn't say anything for a little while, but held on to my hand, and looked so pleased, I wondered at it. Then he said:

"I'm sorry for all the trouble I made them; but I don't mind telling you, Maggie, because you're a real first-class girl, and won't tattle. I was always bothering about how we could have the earthquake. We played everything else of Robinson Crusoe's, you know, but I couldn't see how to get that up." Billy was so eager that he forgot, and tried to lean on his lame elbow. That made him twist his face, but after a moment he smiled again. "Oh, Maggie," said he, "if that cellar had been filled up before we had that earthquake, I never should have been satisfied; but now, you see, I'm even with old Robinson!"

THE DOLLS' WEDDING

I am so glad that the sunshine has driven the clouds away,For my dolly, my darling dolly, is going to be married to-day.She has had a great many suitors—a dozen, I do declare—And only last week, Wednesday, she refused a millionaire.Sophie Read is his mother; she thought we'd feel so grandThat a doll with a diamond stud should offer my child his hand.But Rose cares little for money, and she's given her heart awayTo Charlie, the gallant sailor, who will make her his bride to-day.Nora has made her a bride-cake with frosting as white as snow,And I wove her bridal wreath from the tiniest flowers that blow;And brother Harry has promised (he's ever so kind, I'm sure)To lend them his beautiful yacht when they sail on their wedding tour.We make believe it's the ocean, the lake in the Park, you know;And Charlie, the little sailor, is so delighted to go.Oh, my! he does look cunning in his suit of navy blue.His mother, my most particular friend, is little Nelly Drew.Look! they are coming, Mary. Oh, they are a lovely pair!Charlie, the black-eyed sailor, and Rose with her golden hair.Doesn't she look like a fairy peeping out from a fleecy cloud,In that lovely dress and veil? But we mustn't talk out loud.If I could just squeeze out a tear—I suppose it's the proper thing,Since she is my only child—but indeed I would rather sing,For the sun is shining brightly, and everything seems gay,And to Charlie, the dear little sailor, my dolly is married to-day.THE STORY OF A PARROT

[Continued from No. 2, Page 15.]So many months had passed since I was stolen from my beautiful home that I was already a bird of considerable size. I was brought on shore by a sailor, who took me to a dismal place in a dirty, noisy street, where I found several hundred other birds—parrots, canaries, Java sparrows, and many kinds I had never seen before, confined in small cages. The confusion of sounds was dreadful, and I was sorry to hear that most of the conversation was the most malicious gossip. I was received with shouts of derision, and indeed my appearance was as wretched as possible. My feathers were soiled and broken, and I was overcome with sadness. The air of the place was stifling, and although the man who had charge of me gave me enough to eat, my cage and feed dishes were so dirty that I could not taste a mouthful. Some of my companions showed sympathy for me, and I found a sad consolation in chatting with them; but for all that, the days passed wearily, and I often wished myself dead. My cage was sometimes placed upon a long table in the centre of the room, that I might be inspected by various persons, from whose conversation with my owner I learned that I was for sale. How sadly my thoughts flew back to my poor parents, who would certainly have died of grief had they known of my unfortunate condition, and that I, a free child of the broad African forest, was about to be sold into life-long slavery! So bad-tempered was I (for I plunged furiously at every one who approached me) that no one wished to buy me, and my owner would often say, "That African imp is only fit to kill and stuff." He might kill and stuff me for all I cared, and I made no effort to control my temper.

At last one day a very kind-looking gentleman came in, and stopping before my cage, began to admire the rich color of my plumage. "All he needs is care and kindness to make him a fine bird," he said; and I soon understood that he had ordered me sent to his house.

I LIVED AGAIN IN THE FOREST.

From that day I might have had a pleasant life, but my malicious temper was destined to bring me much farther trouble. My new master appeared very fond of me, and did much for my comfort. I was allowed the liberty of a fine perch, well provided with clean new feed dishes, but, to my intense mortification and disgust, a chain was put upon my feet. My perch stood near a large window, but heavy curtains prevented me from getting more than a single peep of daylight. I saw my new master only for a short time morning and evening, and the solitude was terrible. I sat alone day after day, believing myself to be slowly dying of sadness. I wished that my life could be one long sleep, for when, my head buried in my feathers, I went to the land of dreams, I lived again in the forest where I was born; I saw once more the noble branches of my native tree, and heard the rushing waters of the mighty river on whose banks it stood; I breathed the perfume of thousands of wild flowers; crowds of brilliant birds came hurrying to comfort me; I saw again my father, my mother, my brother, and my sister; I believed myself free once more. Alas! sorrowful was the awaking from all these delights.

"Are you happy?" my master would say. "Have you eaten your breakfast, Lorito?" Yes, indeed, I had breakfasted. I did nothing but eat breakfast from morning till night. I grew very fat, and what was worse, I became so stupid that I repeated like an echo all my master's words. "Have you eaten your breakfast?" I would scream; and my master would laugh, and toss me a lump of sugar. That was my only recreation—to repeat my master's words and eat sugar. I was gradually losing all sense of honor and truth, and to be praised and get a lump of sugar I would rest my beak in my claw and say, with a languishing air, "My head aches; let me alone." My head did ache, too, sometimes, remembering the days when I knew only the language of my fathers, when the sweet voice of my mother waked me in the morning to pass a happy day playing with my brother and sister. Solitude and confinement had soured my character. The rings of my chain hurt my feet so that they were becoming swelled and inflamed. I hated all the world. When my master filled my feed dish with dainties, instead of gratefully accepting his kindness I would seize the dish and spitefully overturn its contents. All day long I screamed as loud as I could, and it gave me the greatest satisfaction when once a policeman came running in great haste to inquire of the house-maid if there was any trouble. "That horrid parrot!" I heard her say, and I laughed as loud as I had screamed before.

One morning my master entered the dining-room, in the window of which stood my perch, followed by a lady and three beautiful children, who rushed toward me eagerly.

"Be careful, Hope," said her father, as the smallest of the three stretched her little hand toward me; "that fellow bites like a savage."

"Poor Rito, he won't bite me," she said, sweetly; but I know I would have done it then, had not the children's mother astonished me by boldly taking me on her hand. "Poor Lorito," she said. "Look at his feet. They are all red and swelled. Anybody would be cross left all alone on a perch with his feet chained together."

She then gently removed my chain, and called the house-maid to carry the perch, with me upon it, to her sitting-room, and to prepare a dish of wine and sugar to bathe my feet.

When I found myself alone in the sitting-room, and had time to think quietly, I realized that a great change had taken place in the house. Three children had come home, and my solitary days were over. They might tease me, perhaps, but at least they would be company. Another thing too I realized, and that was that for the first time I was free. I looked around the room. It was light and sunny, and I could see that it was filled with various pieces of handsome furniture for which parrots have no use. You may be surprised, but to my mind a branch of a tree in a wild forest is infinitely more beautiful and useful than all the fine furniture in the world.

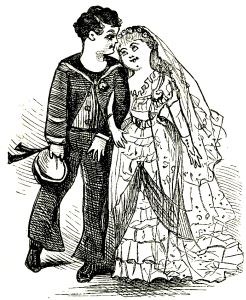

I began slowly to swing myself down from my perch with the intention of making a close inspection of the room. I am almost sure that at first I was more curious than malicious, but, alas! I had scarcely started on my voyage of discovery when I perceived a small blue and gilt bowl standing upon the marble hearth. It contained the sweetened wine ordered as a healing bath for my feet. The fragrance was so enticing that, forgetting the good precepts my mother had taught me, I dipped my beak into the bowl and took a long drink, nor did I stop so long as a single drop remained.

"TEARING OUT NAIL AFTER NAIL."

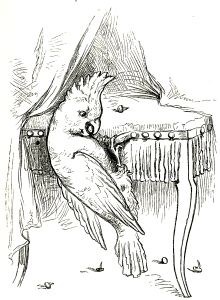

"I WAS BOTH HORRIBLE AND RIDICULOUS."

No sooner had I swallowed the contents of the bowl than I felt a strange burning sensation in my head, which seemed on the point of dancing away from my body. I was possessed of an intense desire to fight something, and I gazed eagerly around the room in the hope of finding some enemy with whom I could engage in mortal combat. I saw no moving thing in the whole apartment which I could attack, but unfortunately my eyes fell upon some shining brass nails which served as ornaments round the edge of a table. To my heated imagination each nail seemed glaring directly at me, menacing me like the evil eye of a bird of prey. I rushed madly toward the table, and climbing up one of its legs, I seized a nail in my beak. To my great delight I found I could easily pull it out, which I immediately did, and threw it spitefully away. With yells of triumph I crept all around the table, clinging with my claws, and tearing out nail after nail as I went, until every one of those aggravating glaring eyes lay scattered over the carpet.

Although I was victorious in my violent battle with the nails, my spirits were not yet calmed. In looking around for a new victim, I saw a bottle standing upon a table in the centre of the room. The old saying that he who drinks once will drink again is one of the truest of proverbs, and I no sooner discovered the bottle than I made all possible haste to reach it, hoping that it contained more sweetened wine. To be sure, the liquid in the bottle was very dark colored, and had an unpleasant odor, but in my eagerness I paid little attention to those things. I tried to taste it, but the mouth of the bottle was too small for my beak, and all my efforts were in vain. In my rage I vowed revenge, and, screaming loudly, I threw the tantalizing thing with violence to the floor.

Alas! my ill behavior was sadly punished. The bottle I had overturned was filled with ink, and I was spattered from head to foot with the vile black mixture. My beautiful plumage, of which I had been so proud, was ruined. I was both horrible and ridiculous. In this miserable and forlorn condition I climbed back upon my perch, and in a most wretched frame of mind waited to be discovered, and perhaps punished.

[to be continued.]A Curious Incident.—Horses will form strong attachments for dogs, but it does not often happen that a horse derives any real benefit from having a canine friend. The following case will show that a dog may sometimes return a horse's affection in a very practical manner. A man living in the country had a horse which happened to be turned out just as his carrots were ready for pulling. He also had a dog that was on the best of terms with the horse. One day he noticed that his carrots were disappearing very fast, but he was almost certain that no one had got in and stolen them. Still he determined to watch, and see who was robbing him. His vigilance was rewarded, for he caught the thief in the very act of pulling up the carrots. Then he cautiously followed him from the garden, and found that he went off in the direction of the field where the horse was. Arrived there, the owner of the carrots saw that his horse was the receiver of his stolen goods. The thief was his dog. In some way the dog had discovered that the horse had a partiality for carrots, and was unable to gratify its taste; but with a sagacity that is almost incredible, the dog found the means of obtaining the succulent morsels for his friend, and this he did without scruple at his master's expense. There was something more than instinct in this dog's head. But any one who takes real notice of the habits and curious doings of animals must inevitably come to the conclusion that the theory is not tenable which maintains that animals can not think and reason.

I was very glad when papa brought me the first number of Young People, and told me I should have it every week. When I read the story of Watty Hirzel, the brave Swiss boy, it made me think of a boy I saw last summer in the Tyrol, where I went with papa and mamma. He was helping his father row a boat on the Königs-See, a beautiful lake in the Bavarian Tyrol. I remember him because he had a bunch of Alpine roses and Edelweiss, which he gave to mamma. We had never seen any flowers like them before, and we wondered if there was any pretty English name for the Edelweiss. Mamma thinks that perhaps if I ask Young People I shall find out. It is a white flower, with leaves like velvet, and the little boatman said it grew very high up on the mountains, where the chamois live.

Mamie.We do not know any pretty English name for Edelweiss. The German name is composed of two words—edel, signifying noble, and weiss, white. If you are studying botany, perhaps you can determine to what family the flower belongs—that is, if you have any carefully pressed specimens.

Will you please tell me why the Bank of England is called "the Old Lady in Threadneedle Street," and who first called it so? I would like to know, too, when the bank was founded, and when the building it now occupies was erected.

Inquisitive Jim.Will not some of our "young people" send answers to "Jim's" questions?

The picture of Chestnutting in the first number of Young People puts me in mind of our beechnutting parties. On the hill where my papa's house stands there are a large number of beech-trees, and I and my two little brothers have just had a fine frolic gathering the queer three-sided little nuts. A beech forest is very beautiful in autumn, when the golden leaves are fluttering down to the ground, and the smooth, straight tree trunks tower upward like silver-gray giants. When we gathered the nuts we spread some old sheets and blankets under the tree, because the nuts are so very small that otherwise we would never have been able to find them among the heaps of dry leaves. They are nestled in russet-brown burrs, something like chestnuts, and are so abundant that sometimes we get a whole barrelful from one tree. We like them better than chestnuts, and they keep all winter. My brothers and myself always take a pocketful to school to eat with our luncheon. We often find them in the spring among the heaps of last year's leaves, and after they have lain under the snow all winter, they begin to sprout when the first warm days come, and then they are very nice to eat.

I hope the Young People will tell us of some good winter-evening games, for we never know what to do between supper and bed-time. We always learn our lessons for the next day in the afternoon.

Susie H. C.WIGGLES

We were scattered about our sitting-room table; the early tea was just over, and a good long evening before us. (Us means papa, Bob, Mamie, and Nelly. I am Nelly, and the eldest of the family—except papa, of course.)

Papa was reading the evening paper—something about stocks, I suppose; Bob had both elbows firmly planted within two inches of the student-lamp, handy for upsetting in case he sneezed; Mamie was looking as doleful as if she had lost her kitten; and I was gazing in the fire and dreaming.

"Wish I had something to do," yawned Bob.

"So do I," said Mamie.

"Play checkers," I suggested.

"No; only two can play that," objected Mamie. "Papa, don't you know something we can play?"

"Well," said papa, folding up his paper, "let me see. Bob, take yourself out of the lamp. Play 'Recondite Forms.'"

"What's recondite?" growled Bob.

"Recondite means hidden, concealed, and this game is called 'Recondite Forms' because— But you will understand it better after you have played it. I want pencils and some rather thin paper."

Bob and Mamie collected the pencils, I brought a supply of French note-paper from my desk, and we all drew our chairs about the table, ready for work.

Papa took a pencil, and made a kind of wiggle, like No. 1 in the picture; then he laid over that another sheet of paper, which was thin enough to allow the pencil mark to show through; this he carefully traced, so as to have an exact copy, and did the same with two other sheets; then gave us each one, and told us to see what kind of a picture we could make out of it; we might add to the line as much as we pleased, but we must not alter nor cross it.