полная версия

полная версияComic History of the United States

As a result of this run on the banks of the Potomac, the North suddenly decided that the war might last a week or two longer than at first stated, that the foe could not be killed with cornstalks, and that a mistake had been made in judging that the rebellion wasn't loaded.6 Half a million men were called for and five hundred million dollars voted. General George B. McClellan took command of the Army of the Potomac.

The battle of Ball's Bluff resulted disastrously to the Union forces, and two thousand men were mostly driven into the Potomac, some drowned and others shot. Colonel Baker, United States Senator from Oregon, was killed.

The war in Missouri now opened. Captain Lyon reserved the United States arsenal at St. Louis, and defeated Colonel Marmaduke at Booneville. General Sigel was defeated at Carthage, July 5, by the Confederates: so Lyon, with five thousand men, decided to attack more than twice that number of the enemy under Price and McCulloch, which he did, August 10, at Wilson's Creek. He was killed while making a charge, and his men were defeated.

General Frémont then took command, and drove Price to Springfield, but he was in a short time replaced by General Hunter, because his war policy was offensive to the enemy. Hunter was soon afterwards removed, and Major-General Halleck took his place. Halleck gave general satisfaction to the enemy, and even his red messages from Washington, where he boarded during the war, were filled with nothing but kindness for the misguided foe.

Davis early in the war commissioned privateers, and Lincoln blockaded the Southern ports. The North had but one good vessel at the time, and those who have tried to blockade four or five thousand miles of hostile coast with one vessel know full well what it is to be busy. The entire navy consisted of forty-two ships, and some of these were not seaworthy. Some of them were so pervious that their guns had to be tied on to keep them from leaking through the cracks of the vessel.

Hatteras Inlet was captured, and Commodore Dupont, aided by General Thomas W. Sherman, captured Port Royal Entrance and Tybee Island. Port Royal became the dépôt for the fleet.

It was now decided at the South to send Messrs. Mason and Slidell to England, partly for change of scene and rest, and partly to make a friendly call on Queen Victoria and invite her to come and spend the season at Asheville, North Carolina. It was also hoped that she would give a few readings from her own works at the South, while her retinue could go to the front and have fun with the Yankees, if so disposed.

HOPED SHE WOULD GIVE A FEW READINGS FROM HER OWN WORKS.

These gentlemen, wearing their nice new broadcloth clothes, and with a court suit and suitable night-wear to use in case they should be pressed to stop a week or two at the castle, got to Havana safely, and took passage on the British ship Trent; but Captain Wilkes, of the United States steamer San Jacinto, took them off the Trent, just as Mr. Mason had drawn and fortunately filled a hand with which he hoped to pay a part of the war-debt of the South and get a new overcoat in London. Later, however, the United States disavowed this act of Captain Wilkes, and said it was only a bit of pleasantry on his part.

The first year of the war had taught both sides a few truths, and especially that the war did not in any essential features resemble a straw-ride to camp-meeting and return. The South had also discovered that the Yankee peddlers could not be captured with fly-paper, and that although war was not their regular job they were willing to learn how it was done.

In 1862 the national army numbered five hundred thousand men, and the Confederate army three hundred and fifty thousand. Three objects were decided upon by the Federal government for the Union army and navy to accomplish,—viz., 1, the opening of the Mississippi; 2, the blockade of Southern ports; and 3, the capture of Richmond, the capital of the Southern Confederacy.

The capture of Forts Henry and Donelson was undertaken by General Grant, aided by Commodore Foote, and on February 6 a bombardment was opened with great success, reducing Fort Henry in one hour. The garrison got away because the land-forces had no idea the fort would yield so soon, and therefore could not get up there in time to cut off the retreat.

Fort Donelson was next attacked, the garrison having been reinforced by the men from Fort Henry. The fight lasted four days, and on February 16 the fort, with fifteen thousand men, surrendered.

Nashville was now easily occupied by Buell, and Columbus and Bowling Green were taken. The Confederates fell back to Corinth, where General Beauregard (Peter G. T.) and Albert Sidney Johnston massed their forces.

General Grant now captured the Memphis and Charleston Railroad; but the Confederates decided to capture him before Buell, who had been ordered to reinforce him, should effect a junction with him. April 6 and 7, therefore, the battle of Shiloh occurred. Whether the Union troops were surprised or not at this battle, we cannot here pause to discuss. Suffice it to say that one of the Federal officers admitted to the author in 1879, while under the influence of koumys, that, though not strictly surprised, he believed he violated no confidence in saying that they were somewhat astonished.

It was Sunday morning, and the Northern hordes were just considering whether they would take a bite of beans and go to church or remain in camp and get their laundry-work counted for Monday, when the Confederacy and some other men burst upon them with a fierce, rude yell. In a few moments the Federal troops had decided that there had sprung up a strong personal enmity on the part of the South, and that ill feeling had been engendered in some way.

SOME OTHER MEN BURST UPON THEM WITH A FIERCE, RUDE YELL.

All that beautiful Sabbath-day they fought, the Federals yielding ground slowly and reluctantly till the bank of the river was reached and Grant's artillery commanded the position. Here a stand was made until Buell came up, and shortly afterwards the Confederates fell back; but they had captured the Yankee camp entire, and many a boy in blue lost the nice warm woollen pulse-warmers crocheted for him by his soul's idol. It is said that over thirty-five hundred needle-books and three thousand men were captured by the Confederates, also thirty flags and immense quantities of stores; but the Confederate commander, General A. S. Johnston, was killed. The following morning the tide had turned, and General P. G. T. Beauregard retreated unmolested to Corinth.

General Halleck now took command, and, as the Confederates went away from there, he occupied Corinth, though still retaining his rooms at the Arlington Hotel in Washington.

The Confederates who retreated from Columbus fell back to Island No. 10 in the Mississippi River, where Commodore Foote bombarded them for three weeks, thus purifying the air and making the enemy feel much better than at any previous time during the campaign. General Pope crossed the Mississippi, capturing the batteries in the rear of the island, and turning them on the enemy, who surrendered April 7, the day of the battle of Shiloh.

May 10, the Union gun-boats moved down the river. Fort Pillow was abandoned by the Southern forces, and the Confederate flotilla was destroyed in front of Memphis. Kentucky and Tennessee were at last the property of the fierce hordes from the great coarse North.

General Bragg was now at Chattanooga, Price at Iuka, and Van Dorn at Holly Springs. All these generals had guns, and were at enmity with the United States of America. They very much desired to break the Union line of investment extending from Memphis almost to Chattanooga.

Bragg started out for the Ohio River, intending to cross it and capture the Middle States; but Buell heard of it and got there twenty-four hours ahead, wherefore Bragg abandoned his plans, as it flashed over him like a clap of thunder from a clear sky that he had no place to put the Middle States if he had them. He therefore escaped in the darkness, his wagon-trains sort of drawling over forty miles of road and "hit a-rainin'."

September 19, General Price, who, with Van Dorn, had considered it a good time to attack Grant, who had sent many troops north to prevent Bragg's capture of North America, decided to retreat, and, General Rosecrans failing to cut him off, escaped, and was thus enabled to fight on other occasions.

The two Confederate generals now decided to attack the Union forces at Corinth, which they did. They fought beautifully, especially the Texan and Missouri troops, who did some heroic work, but they were defeated and driven forty miles with heavy loss.

October 30, General Buell was succeeded by General Rosecrans.

The battle of Murfreesboro occurred December 31 and January 2. It was one of the bloodiest battles of the whole conflict, and must have made the men who brought on the war by act of Congress feel first-rate. About one-fourth of those engaged were killed.

An attack on Vicksburg, in which Grant and Sherman were to co-operate, the former moving along the Mississippi Central Railroad and Sherman descending the river from Memphis, was disastrous, and the capture of Arkansas Post, January 11, 1863, closed the campaign of 1862 on the Father of Waters.

General Price was driven out of Missouri by General Curtis, and had to stay in Arkansas quite a while, though he preferred a dryer climate.

General Van Dorn now took command of these forces, numbering twenty thousand men, and at Pea Ridge, March 7 and 8, 1863, he was defeated to a remarkable degree. During his retreat he could hardly restrain his impatience.

WENT HOME BEFORE THE EXERCISES WERE MORE THAN HALF THROUGH.

Some four or five thousand Indians joined the Confederates in this battle, but were so astonished at the cannon, and so shocked by the large decayed balls, as they called the shells, which came hurtling through the air, now and then hurting an Indian severely, that they went home before the exercises were more than half through. They were down on the programme for some fantastic and interesting tortures of Union prisoners, but when they got home to the reservation and had picked the briers out of themselves they said that war was about as barbarous a thing as they were ever to, and they went to bed early, leaving a call for 9.30 A.M. on the following day.

The red brother's style of warfare has an air about it that is unpopular now. A common stone stab-knife is a feeble thing to use against people who shoot a distance of eight miles with a gun that carries a forty-gallon caldron full of red-hot iron.

CHAPTER XXVI.

SOME MORE FRATRICIDAL STRIFE

The effort to open the Mississippi from the north was seconded by an expedition from the south, in which Captain David G. Farragut, commanding a fleet of forty vessels, co-operated with General Benjamin F. Butler, with the capture of New Orleans as the object.

Mortar-boats covered with green branches for the purpose of fooling the enemy, as no one could tell at any distance at all whether these were or were not olive-branches, steamed up the river and bombarded Forts Jackson and St. Philip till the stunned catfish rose to the surface of the water to inquire, "Why all this?" and turned their pallid stomachs toward the soft Southern zenith. Sixteen thousand eight hundred shells were thrown into the two forts, but that did not capture New Orleans.

Farragut now decided to run his fleet past the defences, and, desperate as the chances were, he started on April 24. A big cable stretched across the river suggested the idea that there was a hostile feeling among the New Orleans people. Five rafts and armed steamers met him, and the iron-plated ram Manassas extended to him a cordial welcome to a wide wet grave with a southern exposure.

Farragut cut through the cable about three o'clock in the morning, practically destroyed the Confederate fleet, and steamed up to the city, which was at his mercy.

The forts, now threatened in the rear by Butler's army, surrendered, and Farragut went up to Baton Rouge and took possession of it. General Butler's occupation at New Orleans has been variously commented upon by both friend and foe, but we are only able to learn from this and the entire record of the war, in fact, that it is better to avoid hostilities unless one is ready to accept the unpleasant features of combat. The author, when a boy, learned this after he had acquired the unpleasant features resulting from combat which the artist has cleverly shown on opposite page.

General Butler said he found it almost impossible to avoid giving offence to the foe, and finally he gave it up in despair.

The French are said to be the politest people on the face of the earth, but no German will admit it; and though the Germans are known to have big, warm, hospitable hearts, since the Franco-Prussian war you couldn't get a Frenchman to admit this.

In February Burnside captured Roanoke Island, and the coast of North Carolina fell into the hands of the Union army. Port Royal became the base of operations against Florida, and at the close of the year 1862 every city on the Atlantic coast except Charleston, Wilmington, and Savannah was held by the Union army.

UNPLEASANT FEATURES RESULTING FROM COMBAT.

The Merrimac iron-clad, which had made much trouble for the Union shipping for some time, steamed into Hampton Roads on the 8th of March. Hampton Roads is not the Champs-Elysées of the South, but a long wet stretch of track east of Virginia,—the Midway Plaisance of the Salted Sea. The Merrimac steered for the Cumberland, rammed her, and the Cumberland sunk like a stove-lid, with all on board. The captain of the Congress, warned by the fate of the Cumberland, ran his vessel on shore and tried to conceal her behind the tall grass, but the Merrimac followed and shelled her till she surrendered.

The Merrimac then went back to Norfolk, where she boarded, night having come on apace. In the morning she aimed to clear out the balance of the Union fleet. That night, however, the Monitor, a flat little craft with a revolving tower, invented by Captain Ericsson, arrived, and in the morning when the Merrimac started in on her day's work of devastation, beginning with the Minnesota, the insignificant-looking Monitor slid up to the iron monster and gave her two one-hundred-and-sixty-six-and-three-quarter-pound solid shot.

The Merrimac replied with a style of broadside that generally sunk her adversary, but the balls rolled off the low flat deck and fell with a solemn plunk in the moaning sea, or broke in fragments and lay on the forward deck like the shells of antique eggs on the floor of the House of Parliament after a Home Rule argument.

Five times the Merrimac tried to ram the little spitz-pup of the navy, but her huge iron beak rode up over the slippery deck of the enemy, and when the big vessel looked over her sides to see its wreck, she discovered that the Monitor was right side up and ready for more.

The Confederate vessel gave it up at last, and went back to Norfolk defeated, her career suddenly closed by the timely genius of the able Scandinavian.

The Peninsular campaign was principally addressed toward the capture of Richmond. One hundred thousand men were massed at Fort Monroe April 4, and marched slowly toward Yorktown, where five thousand Confederates under General Magruder stopped the great army under McClellan.

After a month's siege, and just as McClellan was about to shoot at the town, the garrison took its valise and went away.

On the 5th of May occurred the battle of Williamsburg, between the forces under "Fighting Joe" Hooker and General Johnston. It lasted nine hours, and ended in the routing of the Confederates and their pursuit by Hooker to within seven miles of Richmond. This caused the adjournment of the Confederate Congress.

But Johnston prevented the junction of McDowell and McClellan after the capture of Hanover Court-House, and Stonewall Jackson, reinforced by Ewell, scared the Union forces almost to death. They crossed the Potomac, having marched thirty-five miles per day. Washington was getting too hot now to hold people who could get away.

It was hard to say which capital had been scared the worst.

The Governors of the Northern States were asked to send militia to defend the capital, and the front door of the White House was locked every night after ten o'clock.

But finally the Union generals, instead of calling for more troops, got after General Jackson, and he fled from the Shenandoah Valley, burning the bridges behind him. It is said that as he and his staff were about to cross their last bridge they saw a mounted gun on the opposite side, manned by a Union artilleryman. Jackson rode up and in clarion tones called out, "Who told you to put that gun there, sir? Bring it over here, sir, and mount it, and report at head-quarters this evening, sir!" The artilleryman unlimbered the gun, and while he was placing it General Jackson and staff crossed over and joined the army.

One cannot be too careful, during a war, in the matter of obedience to orders. We should always know as nearly as possible whether our orders come from the proper authority or not.

No one can help admiring this dashing officer's tour in the Shenandoah Valley, where he kept three major-generals and sixty thousand troops awake nights with fifteen thousand men, saved Richmond, scared Washington into fits, and prevented the union of McClellan's and McDowell's forces. Had there been more such men, and a little more confidence in the great volume of typographical errors called Confederate money, the lovely character who pens these lines might have had a different tale to tell.

May 31 and June 1 occurred the battle of Fair Oaks, where McClellan's men floundering in the mud of the Chickahominy swamps were pounced upon by General Johnston, who was wounded the first day. On the following day, as a result of this accident, Johnston's men were repulsed in disorder.

General Robert E. Lee, who was now in command of the Confederate forces, desired to make his army even more offensive than it had been, and on June 12 General Stuart led off with his cavalry, made the entire circuit of the Union army, saw how it looked from behind, and returned to Richmond, much improved in health, having had several meals of victuals while absent.

Hooker now marched to where he could see the dome of the court-house at Richmond, but just then McClellan heard that Jackson had been seen in the neighborhood of Hanover Court-House, and so decided to change his base. General McClellan was a man of great refinement, and would never use the same base over a week at a time.

He had hardly got the base changed when Lee fell upon his flank at Mechanicsville, June 26, and the Seven Days' battle followed. The Union troops fought and fell back, fought and fell back, until Malvern Hill was reached, where, worn with marching, choked with dust, and broken down by the heat, to which they were unaccustomed, they made their last stand, July 1. Here Lee got such a reception that he did not insist on going any farther.

But the Union army was cooped up on the James River. The siege of Richmond had been abandoned, and the North felt blue and discouraged. Three hundred thousand more men were called for, and it seemed that, as in the South, "the cradle and the grave were to be robbed" for more troops.

Lee now decided to take Washington and butcher Congress to make a Roman holiday. General Pope met the Confederates August 26, and while Lee and Jackson were separated could have whipped the latter had the Army of the Potomac reinforced him as it should, but, full of malaria and foot-sore with marching, it did not reach him in time, and Pope had to fight the entire Confederate army on that historic ground covered with so many unpleasant memories and other things, called Bull Run.

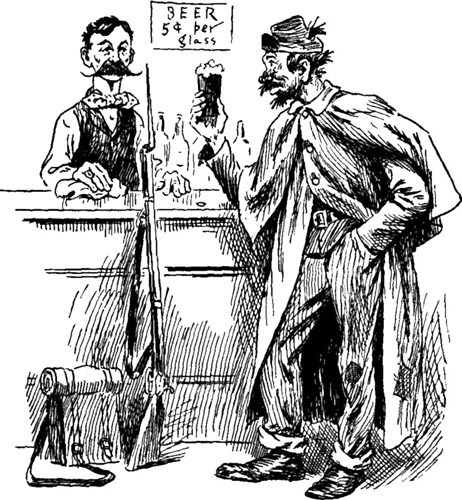

WHERE BEER WAS ONLY FIVE CENTS PER GLASS.

For the second time the worn and wilted Union army was glad to get back to Washington, where the President was, and where beer was only five cents per glass.

Oh, how sad everything seemed at that time to the North, and how high cotton cloth was! The bride who hastily married her dear one and bade him good-by as the bugle called him to the war, pointed with pride to her cotton clothes as a mark of wealth; and the middle classes were only too glad to have a little cotton mixed with their woollen clothes.

WANTS HIS MONEY'S WORTH WHEN HE PAYS FOR A BATTLE.

Lee invaded Maryland, and McClellan, restored to command of the Army of the Potomac, followed him, and found a copy of his order of march, which revealed the fact that only a portion of the army was before him. So, overtaking the Confederates at South Mountain, he was ready for a victory, but waited one day; and in the mountains Lee got his troops united again, while Jackson also returned. The Union troops had over eighty thousand in their ranks, and nothing could have been more thoughtful or genteel than to wait for the Confederates to get as many together as possible, otherwise the battle might have been brief and unsatisfactory to the tax-payer or newspaper subscriber, who of course wants his money's worth when he pays for a battle.

The battle of Antietam was a very fierce one, and undecisive, yet it saved Washington from an invasion by the Confederates, who would have done a good deal of trading there, no doubt, entirely on credit, thus injuring business very much and loading down Washington merchants with book accounts, which, added to what they had charged already to members of Congress, would have made times in Washington extremely dull.

General McClellan, having impressed the country with the idea that he was a good bridge-builder, but a little too dilatory in the matter of carnage, was succeeded by General Burnside.

President Lincoln had written the Proclamation of Emancipation to the slaves in July, but waited for a victory before publishing it. Bull Run as a victory was not up to his standard; so when Lee was driven from Maryland the document was issued by which all slaves in the United States became free; and, although thirty-one years have passed at this writing, they are still dropping in occasionally from the back districts to inquire about the truth of the report.

STILL DROPPING IN OCCASIONALLY FROM THE BACK DISTRICTS.

CHAPTER XXVII.

STILL MORE FRATERNAL BLOODSHED, ON PRINCIPLE.—OUTING FEATURES DISAPPEAR, AND GIVE PLACE TO STRAINED RELATIONS BETWEEN COMBATANTS, WHO BEGIN TO MIX THINGS

On December 13 the year's business closed with the battle of Fredericksburg, under the management of General Burnside. Twelve thousand Union troops were killed before night mercifully shut down upon the slaughter.

The Confederates were protected by stone walls and situated upon a commanding height, from which they were able to shoot down the Yankees with perfect sang-froid and deliberation.

In the midst of all these discouragements, the red brother fetched loose in Minnesota, Iowa, and Dakota, and massacred seven hundred men, women, and children. The outbreak was under the management of Little Crow, and was confined to the Sioux Nation. Thirty-nine of these Indians were hanged on the same scaffold at Mankato, Minnesota, as a result of this wholesale murder.

This execution constitutes one of the green spots in the author's memory. In all lives now and then an oasis is liable to fall. This was oasis enough to last the writer for years.

In 1863 the Federal army numbered about seven hundred thousand men, and the Confederates about three hundred and fifty thousand. Still it took two more years to close the war.