Полная версия

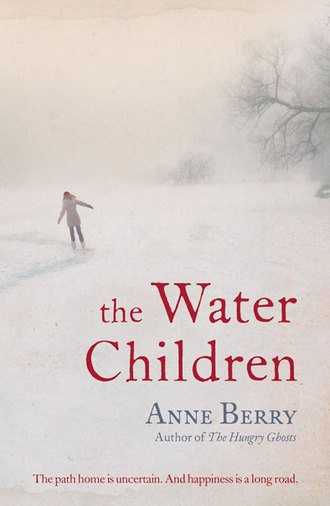

The Water Children

With grim determination she swallows back her dismay. She will act like Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet. She gathers up her money and postal orders now and makes a fan of them in her hand. She flutters them and pulls her lips into a smile. She is overwhelmed by her sudden wealth, but when her father questions her she has no clue what she will spend it all on. Such unexpected largesse and all those things in the shops to choose from. Her parents have given her one of the new Sindy dolls, with curly blonde hair and bold chalk-blue eyes. She is dressed in navy jeans and a red, white and blue stripy sweater. And she has two extra outfits, a glamorous pink dress for her dream dates, and an emergency ward nurse’s uniform.

‘Like it?’ her father asks. Catherine nods. She would have preferred a bike, but she hooks up the corners of her smile valiantly. Keith Hoyle glances surreptitiously at his wife, then relights his pipe which has gone out, with the mother-of-pearl lighter he always keeps in his pocket. He settles back in his chair as if he is not in any hurry at all. ‘Let’s see her done up in all her glad rags then,’ he requests. So, face radiant, Catherine dresses Sindy up in her party outfit and trots her round the crockery.

‘She’s really swinging now,’ he says, when Sindy finally stops jigging by the sugar bowl. Truly he makes Catherine want to laugh. She lets her mind run on him for a while. It is inconceivable that her father will ever be really swinging. He is thin as a beanpole, with a mournful, equine, lined face that appears sun-tanned. This is a bit of a conundrum because he is never in the sun long enough to catch its rays. His hair is very fine, the colour of a silver birch tree, clipped close around his ears and neck, parted to one side like Catherine’s. He massages brilliantine into it before combing it down, which makes it appear as if there is even less of it. It has a funny whiff about it too, rather like an old tweed coat. Her father doesn’t talk a lot either, but it isn’t noticeable because her mother prattles enough for both of them.

Stephen, Catherine’s older brother, has promised that he will call in later on, after the party. He has a job in a garage not far away. The owner lets him stay in one of the spare rooms above the business, so he returns home infrequently, and only to bring his washing or have a hot meal. Catherine thinks he resembles James Dean with his red BSA Bantam motorbike. He is saving for a Triumph Bonneville, and when he finally has enough money to buy it, he has said he will take her all the way to Brighton on it. But today, as it is her birthday, he has promised her a ride to Bushy Park and back instead. Honestly, she is more excited about this than her party, which she feels sure is bound to be a disaster.

Later, as Catherine trails through to the sitting-room to arrange her cards on the mantelpiece over the tiled fireplace, she considers her Uncle Christopher. He is a pilot, which is just about the most romantic thing in the world, she believes. He is handsome in a chiselled kind of way, while Aunt Amy has the grace of a model about her, with her wavy blonde hair, her clear skin, and her calm, low voice. There isn’t a huge gap between Rosalyn and Simon either, not like her and Stephen. Rosalyn is ten and Simon is twelve. And they talk to each other about shared interests, and watch the same programmes on the television sitting side by side. In a way Catherine is a bit frightened of Stephen. After all, he is pretty nearly an adult, and besides there is a strong scent that hangs about him, under the smell of leather and oil. It makes her feel very shy, especially on the rare occasions when she is on his bike with her arms folded about his waist, and the thrumming, dizzying whizz of the machine between her legs.

As she starts up the stairs with her presents, her mother appears in the kitchen doorway, a cigarette in her mouth, a lighter halfway to her lips. Seeing her daughter, she slips it out and wafts it in her direction. ‘You aren’t wearing that dress for the party?’ she calls after her. ‘I told you that the pale pink velvet is best. It’s hanging in the airing cupboard.’

As Catherine lifts it out, despising the fussy, lace neckline, she imagines what it must be like to be a pilot. Her father works in the city. He is a commuter with a hat, not a bowler hat but a hat anyway, and a briefcase. He trudges off to work in creased suits looking exhausted before he’s even left. And he returns grey and even more exhausted, often long after dark. Sometimes when he blows his nose black stuff comes out, which Catherine thinks is revolting, as if he isn’t just black on the outside but is slowly turning black on the inside too. He makes her think of Tom, the chimney sweep, in the book The Water Babies, as if he needs a good scrub to get the engrained dirt out of his pores. But Uncle Christopher goes to work in a smart uniform, one fit for a general or a commander or a president. They are in the back of her mind all day, her aunt, her uncle, Simon, but mostly Rosalyn, though she is determined to make the best of her party.

***

It was Christmas. They were staying in the house in Sussex with the American Hoyles. And it was every bit as amazing as she had imagined it would be. The house was huge, nearly as tall as a castle, redbrick, rectangular and solid, with lots of windows that gleamed like dozens of golden, unblinking eyes in the winter sunshine. And there was a fire-engine red front door that had a brass knocker in the shape of a face with swept-back, wild hair. When you lifted it and banged it down a couple of times it boomed satisfyingly, like a cannon firing. There were lots of bedrooms upstairs and none of them were pokey like Catherine’s. And there was an attic floor that had been converted into yet more rooms. The kitchen was massive, dominated by a milky blue Aga that crunched up scuttles full of coal every morning, while spewing out gusty exhalations of glistening dust.

The lounge was twice the size of theirs. It had wall-to-wall carpet, not just a lino floor with a rug thrown over it. There was a baronial fireplace, in which a real fire crackled and spat and hissed in the grate. It permeated the room with a homely, spicy fragrance, because of the pine logs they fed it, her uncle said. Even her mother, in a rare moment of enthusiasm engendered by the festive season, remarked that it was all rather jolly. Though she added that their built-in bar fire was definitely much cleaner, and probably a lot more efficient – cheaper too, when you con sidered the outrageous cost of fuel.

It was called ‘Wood End’, the stately house, the name painted on a sign at the bottom of the drive. Catherine’s mother admitted grudgingly that it was a suitable name, because the property actually did back onto woods. Another bonus, woods to explore and have adventures in. When they had first approached it in the grey Ford Anglia, puttering along the meandering tree-lined drive, her mother kept reminding her father that the house was only rented, that anyone could afford a house like that for a few weeks.

The property stood in enormous gardens that ran all the way round the house, with no partition dividing the front from the back. There were sweeping lawns and clusters of shrubs and lots of trees. One of them, an ancient oak, with bark like deeply wrinkled skin, only crustier, had a magical tree-house wedged in its branches, with a ladder hanging down from it. There was a separate garage, with double doors, as large as an entire house all by itself, Catherine estimated. They had brought one of the suitcases they usually took on holiday with them, Catherine cleverly sandwiching jeans and jumpers in among the dresses she so hated wearing. She had been overcome with nerves by the time they arrived, she recalled. Dry-mouthed and feeling rather sick, she had climbed out of the car as the American Hoyles piled onto the porch to meet them. This was the moment fated to sully everything, the moment Rosalyn would materialize looking incredibly grown up and aloof, surveying her cousin Catherine with a head-to-toe sweep of her crystal-blue eyes, and turning away, pained.

But that wasn’t what had happened at all. Catherine drooped there, looking frumpy in a patterned corduroy skirt and butterfly collared blouse, and making so many wishes that her head throbbed with them. To be taller, slimmer, to have black or blonde hair, to be dressed fashionably, to instantly shed her chipmunk cheeks, to have a different voice, different parents, to have arrived in a different car, oh, just to be somebody else and not Catherine Hoyle, that would do it, not Catherine the calamity, who didn’t have a single interesting trait in her solid personality.

But a second later and Rosalyn was there, standing before her smiling that self-assured, relaxed smile with the mouth that had never known a quiver. The parents were embracing, voices rising up like startled birds on the crisp morning air. Simon, head tilted, fingers spearing his thick, blond fringe, was hanging back a little, not shyly, just making it clear that he wasn’t up for any of this sloppy stuff. And Rosalyn, who Catherine noted in one stolen peep, had grown taller and even, astounding as it was, prettier, had stepped forward and was wrapping her arms around her and giving her cousin a hug of pure pleasure.

‘Catherine! Oh, it’s brilliant to see you. I’ve got so much to tell you. We’re going to have the best Christmas ever.’

It was a decree. Rosalyn would accept nothing short of perfect. And Catherine felt like Atlas shedding the weighty globe from his bowed shoulders after an eternity of burden. It wasn’t her responsibility if it went badly, not something for her to feel guilty about and to relive agonizingly in the months to come. And she needn’t feel anxious anyway because Rosalyn was going to take care of it. It was going to be the best ever. And you couldn’t jinx her, the way Catherine knew she could be jinxed. If you tried to put a hex on Rosalyn, unfazed, she would gather up the sticky skeins of doom, pat them into a neat ball, and hurl them straight back at you with that dauntless grin, and the sure aim of a girl who was top of the class in PE.

The next moment and she had been delivered into the arms of her aunt, whose embrace was just as genuine, just as sincere, and whose perfume wasn’t sickly sweet like her mother’s but had a subtle soapy aroma. Then her Uncle Christopher bent his tall frame for her to peck him on the cheek, and his skin smelt wonderful too, fresh and clean, not tainted with tobacco, as if bathed in the expanse of glacial blueness above them. Before Catherine knew where she was, Rosalyn had taken her by the hand and was running with her into the house.

‘I want to show you where we’re sleeping,’ she cried excitedly. ‘At the very top, in the attic. We’ve got it all to ourselves.’ Behind her Catherine heard her mother beckon.

‘Catherine. Don’t just dash off, dear. Your father and I need a hand with the bags. Catherine!’ Catherine hesitated at the bottom of the stairs, and her forehead slipped into its familiar groove.

‘Oh never mind about that,’ Rosalyn told her carelessly. ‘They can manage fine. Daddy’s there to help them, and Mummy, and even Simon.’ She was on the third step, her daring blue eyes locked on Catherine’s, still clasping her hand.

‘But—’

She gave the hand a tug. ‘Race you to the top.’ And then she was off, bounding up the stairs two at a time. And Catherine was charging after her, breathless with laughter. She felt as if she was escaping, as if, as they scurried upwards towards the sky, freedom was rushing down to greet her.

‘What do you think?’ Rosalyn demanded, hands on hips, inside the attic bedroom. She was wearing tight jeans and a loose, long-sleeved T-shirt in navy blue, which emphasized her boyish slimness.

Catherine couldn’t gasp as she stepped after her. It wouldn’t have been enough, a paltry gasp in exchange for the sight that met her eyes. It simply would not do. There was a huge bed with an old-fashioned, carved, wooden headboard, and a deep mattress that looked perfect for bouncing on. Above was a large skylight with the morning brightness flooding through it. The floor was cosy with colourful blankets, the walls banked up with cushions and pillows.

‘This is our den. Strictly private. I told Simon. Mummy let me take practically all the spare bedding and cushions for it. And at night we’ll be able to lie in bed and look at the stars. We can tell each other stories about the people who live on the different planets, describe them to one another, make up names for them. It’ll be terrific.’ There was a long pause while Catherine just stared, floor to bed, bed to skylight, skylight to floor, floor to bed. She thought she might cry. But Rosalyn wasn’t having any of that rubbish. ‘Well, put me out of my agony. It took ages to get it just right. Do you like it?’ she asked, giving Catherine a nudge with a swing of her bent arm. Catherine turned to her.

‘I love it. It’s better than perfect,’ she breathed solemnly, and then they were off giggling again.

‘I think we should try out the bed,’ Rosalyn suggested, her shoes already off. ‘Check out the springs. See who can remember the most. I’ve got heaps of new American ones.’

It was a favourite game. They clambered onto the mattress, straightened up, holding onto each other like two fragile old ladies who’d had one tipple too many, and started to leap as high as they could, bumping frequently.

‘A free glass. Yours for the price of Duz,’ yelled Rosalyn, her hair flying across her face.

‘Caramel Wafers by Gray Dunn, a crunchy treat for everyone,’ retorted Catherine through her chuckles.

‘Get that lovely, lively, Lyril feeling,’ crooned Rosalyn into a make-believe microphone.

‘Spirella, they’ll like the way you look,’ Catherine thundered back.

The words of the jingles kept pace with their jumps.

‘You’re never alone with a Strand.’ Again her cousin mimed, only this time elegantly smoking.

‘Diana – the big picture paper for girls!’ sang back Catherine.

‘Cadum for Madam. Cadum for Madam.’ Now Rosalyn set about lathering up her face with an imaginary bar of soap.

‘Rinso white, Rinso bright,’ Catherine broke off to rub her hands. ‘Happy little washday song!’

‘Wake up your liver with Calomel,’ panted Rosalyn.

Rosalyn won in the end, but Catherine didn’t mind. She’d kept going for ages and had acquitted herself fairly well, she thought.

‘You’re getting really good,’ complimented Rosalyn, not in a patronizing way either, and Catherine blushed at the compliment.

Eventually they fell over in a tangled heap, their heads still spinning, laughing hysterically until Catherine’s tummy felt sore. And just when they were calming down, Rosalyn got them both going again, because she squealed that she was going to wet herself if they didn’t stop. Then, as though attached at the hip, they rolled onto their backs and stretched out like stars. Rosalyn’s arm lay across Catherine’s chest. Catherine’s leg lay over Rosalyn’s thighs. They shared a sublime sigh. Catherine took stock of her cousin with a sideways glance. She was the same but different. Taller, yes, and she seemed to be growing into her athletic build: long legs, broad shoulders, her mother’s classic facial bone structure. She had cut her black hair. It was a blue-black shade she had inherited from her father. As the light fell on it, the dark tresses shimmered with traces of purple, green and gold. It suited her, gave an impish, gamine quality to her face. And the blue eyes, well, they had grown more dazzling, more full of merriment, more mischievous.

Later on in the afternoon Stephen arrived on his motorbike. He roared up the drive looking more like James Dean than ever, and they rushed out to meet him. For ages, still sitting on his bike and rocking it to either side, then rolling it forward half a foot and back again, he held court. Simon was terribly impressed. He hunkered down, peered interestedly at the mechanics of the thing, and kept asking questions. Rosalyn and Catherine struck a haughty pose, their weight on one hip each, regarding Stephen coolly, until he offered to give them rides up and down the drive. Then in a second they lost all their contrived composure, and hopped about as though an electric current was pulsing through their veins.

As Rosalyn had ordered, all continued without a hitch. A walk in the woods, filling bags with snippets of prickly, dark-green holly studded with blood-red berries, collecting knobbly fir cones and spruce boughs that smelt of pine sap, to deck the house. Rosalyn storytelling in their tree-house retreat, which enchantingly had its own dear ceiling light. Tea of toad-in-the-hole, crispy batter pudding and sausages that were cooked just right. Television – a double episode of Supercar. A bubble bath, where they fashioned wigs and moustaches of sparkling soapsuds. And then, Catherine, not minding about her tartan ladybird pyjamas with the elasticized wristbands, because Rosalyn didn’t even seem to see them as they lay in bed in the enchanted darkness, star gazing.

Rosalyn told Catherine all about America, her school and her friends, and how terrible the assassination of John Kennedy had been last month, in Dallas, Texas, and that everyone was dreadfully sad about it. And Catherine managed a short extempore speech about her own school, in which she made up a friend called Karen, who had her own horse which she rode on weekends.

Even Christmas Day, notorious for scenes in Catherine’s experience, with her mother feeling so put upon, went well. Everyone lent a hand cheerfully, the seasonal songs tra-la-la-ing from the radio. The snow fell on Boxing Day and quilted the scenery in virgin white, so that it looked like a sparkling picture on a Christmas card. Catherine wasn’t sure whose idea it was to go for a walk, perhaps even find out if the pond that was too large for a pond and too small for a lake, had frozen over. They left their mothers nattering in the kitchen, peeling vegetables and preparing lunch, their fathers, in the lounge having a serious discussion about something called the Profumo affair, and debating whether or not a Labour government would get in next year, and Simon transfixed by Stephen tinkering with his motorbike in the garage.

For a while it felt like they just walked aimlessly. It had turned a good deal colder and they were both bundled up in coats, gloves and scarves, Rosalyn wearing a red beret that looked so dramatic against her shiny black hair. They found their way to the end of the drive, then to the end of the lane, pausing to throw snowballs at one another. They discussed making a snowman that very afternoon, getting the boys to help. Then Rosalyn mentioned the pond again and they set off more purposefully this time, pushing their way through the copse that bordered the lane, sending the canopy of snow scattering in little flurries. For a short distance the growth was fairly dense. Dry, frosty twigs snapped with sharp reports as they shouldered their way through. A robin looked on inquisitively when Catherine tripped into a hollow hidden by the lambent carpet. But she wasn’t hurt and she was quick to assure Rosalyn of it, and to dismiss her suggestions that they turn back. The sky had a yellowish tint to it that possibly meant more snow. The low sun had not yet broken through the layers of clouds. The uneven ground they trudged over with its mounds and dips, looked like a lunar landscape with, here and there, a skeletal tree throwing up its bony branches in desolation.

It was very quiet. The snow seemed to soundproof the setting, so that they had that shut-off feeling Catherine had known when Stephen had taken her to a recording studio. They were a long way from the lane now, a long way from the house in its relatively deserted location, a long way from the main road, from cars, from people. Catherine was dimly aware of a shift in both of their demeanours. The casual wandering had become a determined trek, the destination they sought was the pond. It was unthinkable to them now that they should retrace their steps and abandon the mission. Like mountaineers seeking the summit of a challenging peak, or arctic explorers following a planned route in rigorous conditions, turning back was not an option. Their conversation had grown sporadic, then hiccupped into a quiet that neither wanted to break.

They were still, more or less, walking companionably side by side, one slipping down a small slope and then speedily clambering upright again, the other circumventing a split tree-trunk and bending to brush snow off her boots, then the two of them falling into step again. Neither felt cold because of the exercise. They watched each other’s breaths misting the chilled air. The pond was screened by a thicket of saplings and bracken, so that when they finally fought their way through and came upon the winter oasis, they were both awed by the scene.

The hoop of vegetation stood out in dark relief against the pallid sky. The banks, blanketed in white, canted down to an iced mirror of frozen water, edged with hoary reeds. They could just glimpse dusky shapes looming up from the opaque depths.

‘It’s beautiful,’ said Rosalyn, taking in the zinc-grey gleam.

‘You were right, it’s iced over,’ said Catherine, wonder-struck.

‘Our own private skating rink,’ said Rosalyn covetously. Their eyes met, blue and green, and both alight with devilry. ‘Can you skate?’ Rosalyn wanted to know. She crouched down and started to make her descent, knees bent, gloved hands searching the snow for a hold of woody stems or sunken rocks.

‘Of course,’ said Catherine, following her. This was untrue, but then how complicated could it be? You slid your feet on the ice, skidded, skated. This would be much easier than trying to balance on real skates, the ones she had seen on television with flashing silver blades, the ones that cut the ice with a hiss, sending a fine spray flying up. She followed Rosalyn. When they arrived at the place where the ice began they both stopped and faced each other. Catherine thought Rosalyn had never looked lovelier. Her skin was very smooth and white, except on the rounds of her cheeks, which were flushed rosy red with the cold. Her mouth was leaning towards a smile. The irises of her vivid blue eyes were ringed in a velvety indigo. Her abundant glossy curls were such a contrast to the scarlet beret pulled down over them, each accentuating the vibrant colour of the other. Yes, she was truly lovely, Catherine thought. Then the sequential thought, that she should like to remember her just like this, a snapshot that she could carry in her head forever. She shivered involuntarily.

‘Cold?’ Rosalyn asked.

‘No . . . no,’ she answered a trifle hesitantly, because now they had stopped walking she did feel cold tentacles worming their way through her layers of clothing.

‘Oh, come on. Last one on the ice is a rotten pig,’ teased Rosalyn.

And then she was pushing off from the bank, rising to her feet until she was standing tall on the frozen platform. She slid forwards once again, flapped her boots against the ice to check that it was solid. Satisfied, she slid a few more steps. Now Catherine was on her feet too. Copying her cousin, she traced her silvery snail trails on the ice with her boots. Rosalyn was gaining in confidence, her feet arcing out as if she was on a real rink. She was putting all her weight on one foot as well, the other foot flicking up behind her. Catherine was nowhere near as adept as her cousin was. Rosalyn had actually skated on several rinks in America, she called over her shoulder. There was nothing to it. Of course, it would be much better if they had proper skates, but then they had their own rink, so they really couldn’t complain. Catherine slid forward gingerly, but either the soles of her boots were not the slippery kind or she was plain hopeless; she suspected the latter.

Rosalyn was heading for the centre of the large pond, her progress as fluid as a boat bug. Catherine, who had only narrowly avoided falling over by flexing her knees just in time, and propping herself up, hands flat on the ice, arms braced, had just succeeded in standing up again. She was concentrating hard, but glimpsing up, saw how far Rosalyn had gone, that she was nearing the middle of the pond. She herself was still only a couple of yards from the bank. The red beret swooped before her eyes.