Полная версия

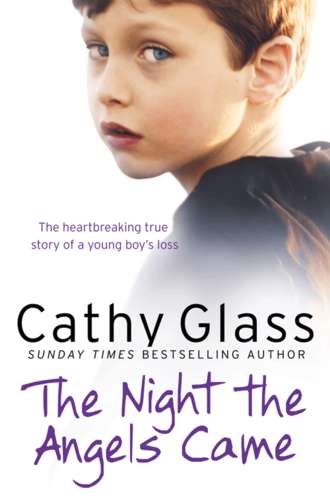

The Night the Angels Came

Some time later, feeling pretty despondent, I ejected Toscha from my lap and, heaving myself off the sofa, left the sitting room. I went into the kitchen, where I began clearing away the breakfast dishes, my thoughts returning again and again to Patrick and Michael. Was I being selfish in asking to meet Patrick first before making a decision? Jill had implied I was. The poor man had enough to cope with without a foster carer dithering about looking after his son because it would be too upsetting.

It was an hour before the phone rang again and it was Jill. ‘Right, Cathy,’ she said, her voice businesslike but having lost its sting of criticism. ‘I’ve spoken to Stella, the social worker involved in Michael’s case, and she’s phoned Patrick. Stella put your suggestion – of meeting before you both decide if your family is right for Michael – to Patrick, and Patrick thinks it’s a good idea. In fact, Stella said he sounded quite relieved. Apparently he has some concerns, one being that you are not practising Catholics as they are. So that’s one issue we will need to discuss.’

I too was relieved and I felt vindicated. ‘I’ll look forward to meeting him, then,’ I said.

‘Yes, and we need to get this moving, so Stella has set up the meeting for ten a.m. tomorrow, here at the council offices. The time suits Patrick, Stella and me, and I thought it should be all right with you as Paula will be at nursery.’

‘Yes, that’s fine,’ I said. ‘I’ll be there.’

‘I’m not sure which room we’ll be in, so I’ll meet you in reception.’

‘OK. Thanks, Jill.’

‘And can you bring a few photos of your house, etc., to show Patrick?’

‘Will do.’

When I met the children later in the day – Paula from nursery at 12 noon, and Adrian from school at 3.15 p.m. – the first question they asked me was: ‘Is Michael coming to live with us?’ I said I didn’t know yet – that I was going to a meeting the following morning where Patrick and the social workers would be present and we’d decide after that, which they accepted. The subject of Michael wasn’t mentioned again during the evening, although it didn’t leave my thoughts for long. Somewhere in our community, possibly not very far from where I lived, there was a young lad, Adrian’s age, who was about to lose his father; while a relatively young father was having to come to terms with saying goodbye to his son for good. It had forced me to confront my own mortality, and later I realized it had unsettled Adrian and Paula too.

At bedtime Paula gave me an extra big hug; then, as she tucked her teddy bear in beside her, she said, ‘My teddy is very ill, Mummy, but the doctors are going to make him better. So he won’t die.’

‘Good,’ I said. ‘That’s what usually happens.’

Then when I went into Adrian’s bedroom to say goodnight he asked me outright: ‘Mum, you’re not going to die soon, are you?’

I bloody hope not! I thought.

I sat on the edge of his bed and looked at his pensive expression. ‘No. Not for a long, long time. I’m very healthy, so don’t you start worrying about me.’ Clearly I didn’t know when I was going to die, but Adrian needed to be reassured, not enter into a philosophical debate.

He gave a small smile, and then asked thoughtfully, ‘Do you think there’s a God?’

‘I really don’t know, love, but it would be nice to believe there is.’

‘But if there is a God, why would he let horrible things happen? Like Michael’s father dying, and earthquakes, and murders?’

I shook my head sadly. ‘I don’t know. Sometimes people who have a faith believe they are being tested – to see if their faith is strong enough.’

Adrian looked at me carefully. ‘Does God test those who don’t have a faith?’

‘I really don’t know,’ I said again. I could see where this was leading.

‘I hope not,’ Adrian said, his face clouding again. ‘I don’t want to be tested by having something bad happen. I think if God is good and kind, then he should stop all the bad things happening in the world. It’s not fair if bad things happen to some people.’

‘Life isn’t always fair,’ I said gently, ‘faith or no faith. And we never know what’s around the corner, which is why we should make the most of every day, which I think we do.’

Adrian nodded and laid his head back on his pillow. ‘Maybe I should do other things instead of watching television.’

I smiled and stroked his forehead. ‘It’s fine to watch your favourite programmes; you don’t watch that much television. And Adrian, please don’t start worrying about any of us dying; what’s happened in Michael’s family is very unusual. How many children do you know who lost one parent when they were little and are about to lose their other parent? Think of all the children in your school. Have you heard of anyone there?’ I wanted to put Michael’s situation into perspective: otherwise I knew Adrian could start worrying that he too could be left orphaned.

‘I don’t know anyone like that at school,’ he said.

‘That’s right. Adults usually live for a long, long time and slowly grow old. Look at Nana and Grandpa. They are fit and healthy and they’re nearly seventy.’

‘Yes, they’re very old,’ Adrian agreed. And while I wasn’t sure my parents would have appreciated being called ‘very old’, at least I had made my point and reassured Adrian. His face relaxed and lost its look of anguish. I continued to stroke his forehead and his eyes slowly closed. ‘I hope Michael can come and stay with us,’ he mumbled quietly as he drifted off to sleep.

‘We’ll see. But if it’s not us then I know whoever it is will take very good care of him.’

Chapter Four So Brave Yet So Ill

I usually meet the parent(s) of the child I am looking after once the child is with me. I might also meet them regularly at contact, when the child sees his or her parents; or at meetings arranged by the social services as part of the childcare proceedings. Sometimes the parents are cooperative and we work easily together with the aim of rehabilitating the child home. Other parents can be angry with the foster carer, whom they see as being part of ‘the system’ responsible for taking their child into care. In these cases I do all I can to form a relationship with the parent(s) so that we can work together for the benefit of their child. I’ve therefore had a lot of experience of meeting parents in the time I’ve been fostering, but I couldn’t remember ever feeling so anxious and out of my depth as I did that morning when I entered the reception area at the council offices and looked around for Jill.

Thankfully I spotted her straightaway, sitting on an end seat in the waiting area on the far side. She saw me, stood and came over. ‘All right?’ she asked kindly, lightly touching my arm. I nodded and took a deep breath. ‘Try not to worry. You’ll be fine. We’re in Interview Room 2. It’s a small room but there’s just the four of us. Stella, the social worker, is up there already with Patrick. I’ve said a quick hello.’

I nodded again. Jill turned and led the way back across the reception area and to the double doors that led to the staircase. There was a lift in the building but it was tiny and was usually reserved for those with prams or mobility requirements. I knew from my previous visits to the council offices that the interview rooms were grouped on the first floor, which was up two short flights of stairs. But as our shoes clipped up the stone steps I could hear my heart beating louder with every step. I was worried sick: worried that I’d say the wrong thing to Patrick and upset him, or that I might not be able to say anything at all, or even that I would take one look at him and burst into tears.

At the top of the second flight of stairs Jill pushed open a set of swing doors and I followed her into a corridor with rooms leading off, left and right. Interview Room 2 was the second door on the right. I took another deep breath as Jill gave a brief knock on the door and then opened it. My gaze went immediately to the four chairs arranged in a small circle in the centre of the room, where a man and a woman sat facing the door.

‘Hi, this is Cathy,’ Jill said brightly.

Stella smiled as Patrick stood to shake my hand. ‘Very pleased to meet you,’ he said. He was softly spoken with a mellow Irish accent.

‘And you,’ I said, relieved that at least I’d managed this far without embarrassing myself.

Patrick was tall, over six feet, and was smartly dressed in dark blue trousers, light blue shirt and navy blazer, but he had clearly lost weight. His clothes were too big for him and the collar on his shirt was very loose. His cheeks were sunken and his cheekbones protruded, but what I noticed most as we shook hands were his eyes. Deep blue, kind and smiling, they held none of the pain and suffering he must have gone through and indeed was probably still going through.

We sat down in the small circle. I took the chair next to Jill so that I was facing Patrick and had Jill on my right and Stella on my left.

‘Shall we start by introducing ourselves?’ Stella said. This is usual practice in meetings at the social services, even though we might all know each other or, as in this case, it was obvious who we were. ‘I’m Stella, Patrick and Michael’s social worker,’ Stella began.

‘I’m Jill, Cathy’s support social worker from Homefinders fostering agency,’ Jill said, looking at Patrick as she spoke.

‘I’m Cathy,’ I said, smiling at Patrick, ‘foster carer.’

‘Patrick, Michael’s father,’ Patrick said evenly. ‘Thank you,’ Stella said, looking around the group. ‘Now, we all know why we’re here: to talk about the possibility of Cathy fostering Michael. I’ll take a few notes of this meeting so that we have them for future reference, but I wasn’t going to produce minutes. Is that all right with everyone?’

Patrick and I nodded as Jill said, ‘Yes.’ Jill, as at most meetings she attended with me, had a notepad open on her lap so that she could make notes of anything that might be of help to me later and which I might forget. Now I was in the room and had met Patrick, I was starting to feel a bit calmer. My heart had stopped racing, although I still felt pretty tense. Everyone else appeared quite relaxed, even Patrick, who had his hands folded loosely in his lap.

‘Cathy,’ Stella said, looking at me, ‘I think it would be really useful if we could start with you telling us a bit about yourself and your family. Then Patrick,’ she said, looking at him, ‘would you like to go next and tell Cathy about you and Michael?’

Patrick nodded, while I straightened in my chair and tried to gather my thoughts. I don’t like being first to talk at meetings, although I’m a lot better now at speaking in meetings than I used to be when I first began fostering; then I used to be so nervous I became tongue-tied and unable to say what I wanted to. ‘I’ve been a foster carer for nine years,’ I began. ‘I have two children of my own, a boy and a girl, aged eight and four. I was married but unfortunately I’m now separated and have been for nearly two years. My children have grown up with fostering and enjoy having children staying with us. They are very good at helping the child settle in. It’s obviously very strange for the child when they first come to stay and they often talk to Adrian and Paula before they feel comfortable talking to me.’ I hesitated, uncertain of what to say next.

‘Could you tell us what sort of things you do at weekends?’ Jill suggested.

‘Oh yes. Well, we go out quite a lot – to parks, museums and places of interest. Sometimes to the cinema. And we see my parents, my brother and my cousins quite regularly. They all live within an hour’s drive away.’

‘It’s nice to do things as a family,’ Patrick said.

‘Yes,’ I agreed. ‘We’re a close family and obviously the child we look after is always included as part of our family and in family activities. I make sure all the children have a good Christmas and birthday,’ I continued. ‘And in the summer we try and go on a short holiday, usually to the coast in England.’ Patrick nodded. ‘I encourage the children in their hobbies and interests and I always make sure they are at school on time. If they have any homework I like them to do it before they play or watch television.’ I stopped and racked my brains for what else I should tell him. It was difficult giving a comprehensive thumbnail sketch of our lives in a few minutes.

‘Did you bring some photographs?’ Jill prompted.

‘Oh yes. I nearly forgot.’ I delved into my bag and took out the envelope containing photos that I had hastily robbed from the albums that morning. I passed them to Patrick and we were all quiet for some moments as he looked through them. There were about a dozen, showing my family in various rooms in the house, the garden, and also our cat, Toscha. Had I had more notice I would have put a small album together and labelled the photos.

Patrick smiled. ‘Thank you,’ he said, returning the photos to the envelope and then handing them back to me. ‘You have a lovely family and home. I’m sure if Michael stayed with you he would feel very comfortable.’

‘Thank you,’ I said.

‘Can I have a look at the photos?’ Stella asked. I passed the envelope to her. ‘While I look at these,’ she said to Patrick, ‘perhaps you’d like to say a bit about you and Michael?’

Patrick nodded, cleared his throat and shifted slightly in his chair. He looked at me as he spoke. ‘First, Cathy, I would like to thank you for coming here today and considering looking after my son when I am no longer able to. I can tell from the way you talk that you are a caring person and I know if Michael comes to stay with you, you will look after him very well.’ I gave a small smile and swallowed the lump rising in my throat as Patrick continued, so brave yet so very ill. Now he was talking I could see how much effort it took. He had to pause every few words to catch his breath. ‘It will come as no surprise to you to learn I was originally from Ireland,’ he continued with a small smile. ‘I know I haven’t lost my accent, although I’ve been here nearly twenty years. I came here when I was nineteen to work on the railways and liked it so much I stayed.’ Which made Patrick only thirty-nine years old, I realized. ‘Unfortunately I lost both my parents to cancer while I was still a young man. Cathy, you are very lucky to have your parents, and your children, grandparents. Cherish and love them dearly; parents are a very special gift from God.’

‘Yes, I know,’ I said, feeling my eyes mist. Get a grip, I told myself.

‘Despite my deep sadness at losing both my parents so young,’ Patrick continued, ‘I had a good life. I earned a decent wage and went out with the lads – drinking too much and chasing women, as Irish lads do. Then I met Kathleen and she soon became my great love. I gave up chasing other women and we got married and settled down. A year later our darling son, Michael, was born. We were so very happy. Kathleen and I were both only children – unusual for an Irish family – but we both wanted a big family and planned to have at least three children, if not four. Sadly it was not to be. When Michael was one year old Kathleen was diagnosed with cancer of the uterus. She died a year later. She was only twenty-eight.’

He stopped and stared at the floor, obviously remembering bittersweet moments from the past. The room was quiet. Jill and Stella were concentrating on their notepads, pens still, while I looked at the envelope of photographs I still held in my hand. So much loss and sadness in one family, I thought; it was so unfair. But cancer seems to do that: pick on one family and leave others free.

‘Anyway,’ Pat said casually, after a moment. ‘Clearly the good Lord wanted us early.’

I was taken aback and wanted to ask if he really believed that, but it didn’t seem appropriate.

‘To the present,’ Patrick continued evenly. ‘For the last six years, since my dear Kathleen was taken, there’s just been Michael and me. I didn’t bring lots of photos with me, but I do have one of Michael which I carry everywhere. Would you like to see it?’

I nodded. He tucked his hand into his inside jacket pocket and took out a well-used brown leather wallet. I watched, so touched, as Patrick’s emaciated fingers trembled slightly and he fumbled to open the wallet. Carefully sliding out the small photo, about two inches square, he passed it to me.

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘What a smart-looking boy!’

Patrick smiled. ‘It’s his most recent school photo.’

Michael sat upright in his school uniform, hair neatly combed, slightly turned towards the camera, with a posed impish grin on his face. There could be no doubt he was Patrick’s son, with his father’s blue eyes, pale complexion and pleasant expression: the likeness was obvious.

‘He looks so much like you,’ I said as I passed the photo to Jill.

Patrick nodded. ‘And he’s got my determination, so don’t stand any nonsense. He knows not to answer back and to show adults respect. His teacher says he’s a good boy.’

‘I’m sure he is a real credit to you,’ I said, touched that Patrick should be concerned that his son’s behaviour didn’t deteriorate even when he was no long able to oversee it.

Jill showed the photograph to Stella and handed it back to Patrick. Patrick then went on to talk a bit about Michael’s routine, foods he liked and disliked, his school and favourite television programmes, all of which I would talk to him about in more detail if Michael came to stay with us. Patrick admitted his son hadn’t really had much time to pursue interests outside the home because of Patrick’s illness and having to help his father, although Michael did attend a lunchtime computer club at school. ‘I’m sure there are a lot of things I should have told you that I’ve missed,’ Patrick wound up, ‘so please ask me whatever you like.’

‘Perhaps I could step in here,’ Stella said. We looked at her. ‘I think the first issue we should address is the matter of Michael’s religion. Patrick and Michael are practising Catholics and Cathy’s family are not. How do you both feel about that?’ She looked at Patrick first.

‘Well, I won’t be asking Cathy to convert,’ he said with a small laugh. ‘But I would like Michael to keep attending Mass on a Sunday morning. If Cathy could take and collect him, friends of mine who also go can look after him while he’s there. I’ve been going to the same church a long time and the priest is aware of my illness, and does what he can to help.’

‘Would this arrangement work?’ Stella asked me.

‘Yes, I don’t see why not,’ I said, although I realized it would curtail us going out for the day each Sunday.

‘If you had something planned on a Sunday,’ Patrick said, as if reading my thoughts, ‘Michael could miss a week or perhaps he could go to the earlier mass at eight a.m.?’

‘Yes, that’s certainly possible,’ I said.

‘Thank you,’ Patrick said. Then quietly, almost as a spoken afterthought, ‘I hope Michael continues to go to church when I’m no longer here, but obviously that will be his decision.’

‘So can we just confirm what we have decided?’ Stella said, pausing from writing on her notepad. ‘Patrick, you don’t have a problem with Cathy not being a Catholic as long as Michael goes to church most Sundays?’

‘That’s right.’ He nodded.

‘And Cathy, you are happy to take Michael to church and collect him, and generally encourage and support Michael’s religion?’

‘Yes, I am.’

Both Jill and Stella made a note. Patrick and I exchanged a small smile as we waited for them to finish writing.

Stella looked up and at me. ‘Now, if this goes ahead, and we all feel it is appropriate for Michael to come to you, I know Patrick would like to visit you with Michael before he begins staying with you. Is that all right with you, Cathy?’

‘Yes.’

‘Thank you, Cathy,’ Patrick said. ‘It will help put my mind at rest if I can picture my son in his new bed at night.’

‘It’ll give you both a chance to meet my children as well,’ I said.

Jill and Stella both wrote again. ‘Now, to the other question Michael has raised with me,’ Stella said: ‘hospital visiting. When Patrick is admitted to hospital or a hospice, will you be able to take Michael to visit him?’

‘Yes, although I do have my own two children to think about and make arrangements for. Would it be every day?’

‘I would like to see Michael every day if possible, preferably after school,’ Patrick confirmed.

‘And at weekends?’ Jill asked.

‘If possible, yes.’

It was obviously a huge undertaking, and while I could see that of course father and son would want to see as much of each other as possible I was wondering about the logistics of the arrangement, and also how Adrian and Paula would feel at being bundled into the car each day after school and driven across town to the hospital instead of going home and relaxing.

‘Were you thinking Cathy would stay for visiting too?’ Jill asked, clearly appreciating my unspoken concerns.

‘Not necessarily,’ Patrick said. ‘Cathy has her own family to look after and Michael is old enough to be left in the hospital with me. It would just need someone to bring and collect him.’

‘If Cathy wasn’t able to do it every day,’ Jill said to Patrick, ‘would you be happy if we used an escort to bring and collect Michael? We use escorts for school runs sometimes. All the drivers are vetted.’

‘Yes, that’s fine with me,’ he said. ‘It shouldn’t be necessary for a long time, as I intend staying in my home for as long as possible, until I am no longer able to look after myself.’ Which made me feel small-minded and churlish for not agreeing to the arrangement outright.

‘It’s not a problem,’ I said quickly. ‘I’ll make sure Michael visits you every day.’

‘Thank you, Cathy,’ Patrick said, then with a small laugh: ‘And don’t worry, you won’t have to arrange my funeral: I’ve done it.’

I met Patrick’s gaze and hadn’t a clue what to say. I nodded dumbly. Jill and Stella made no comment either, for what could we possibly say?

‘So,’ Stella said, after a moment, ‘do either of you have any more questions or issues you wish to explore?’

I shook my head. ‘I don’t think so,’ I said. ‘No,’ Patrick said. ‘I would like it if Cathy agreed to look after Michael. I would be very grateful.’

I was looking down again, concentrating on the floor. ‘And what is your feeling, Cathy?’ Stella asked. ‘Or would you like some time to think about it?’

‘No, I don’t need more time,’ I said. ‘And Patrick deserves an answer now.’ I felt everyone’s eyes on me. Especially Jill on my right, who, I sensed, was cautioning me against saying something I should take time to consider. ‘I will look after Michael,’ I said. ‘I’d be happy to.’

‘Thank you,’ Patrick said. ‘God bless you.’ And for the first time I heard his voice tremble with emotion.

Chapter Five Treasure

Usually, once I’ve made a decision I’m positive and just get on with the task in hand. But now, as I left the council offices and began the drive to collect Paula from nursery, I was plagued with misgiving and doubt. Had I made the right decision in offering to look after Michael or had I simply felt sorry for Patrick? What effect would it have on Adrian and Paula? What effect would it have on me? Then I thought of Patrick and Michael and all they were going through and immediately felt guilty and selfish for thinking of myself.

I switched my thoughts and tried to concentrate on the practical. At the end of the meeting we’d arranged for Patrick and Michael to visit the following evening at 6.00. I now considered their visit and what I could do to make them feel relaxed and at home. Although I’d had parents visit prior to their child staying before, it was very unusual. One mother had visited prior to her daughter staying when she was due to go into hospital (she didn’t have anyone else to look after her child); another set of parents had visited before their son (with very challenging behaviour) had begun a respite stay to give them a break. Both children were in care under a voluntary care order (now called a Section 20), where the parents retain all legal rights and responsibilities. This was how Michael would be looked after, but that was where any similarity ended: the other children had returned home to their parents. And whereas the other visits had been brief – I’d showed the family around the house and explained our routine – I thought Patrick and Michael’s visit needed to be more in-depth, to give them a feeling of our home life which would, I hoped, reassure them both. I decided the best way to do this would be for us to try and carry on as ‘normal’, and then tormented myself by picturing Patrick and Michael sitting on the sofa and Adrian and Paula staring at them in silence.