Полная версия

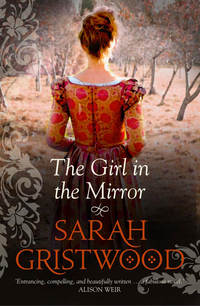

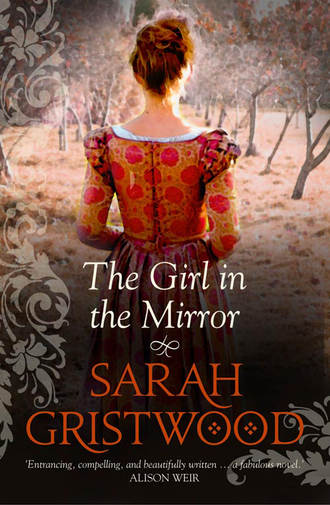

The Girl in the Mirror

Master Hill paid Jacob to keep his accounts, and to write his letters neatly. So did other businessmen, one by one, and not all of them Dutch or French, though it helped that, besides the Latin, he spoke three languages easily. Four, in the end, for he came to teach himself Italian, and in doing so to teach me. He hadn’t the time or the patience to school a child in the rudiments, so I learnt to read and recite, and figure, at the petty school. I learnt to write there, too, but Jacob said it was a vile, clumsy hand they were teaching me. He said it to the dame, who announced the next day she wanted no more to do with me. So I stayed at home, and imitated Jacob’s beautiful curling writing, and ran loose in the shelves of his growing library as if in a row of peas. He was friends with all the booksellers around St Paul’s, and when he went to see them, he took me.

He made more than enough money to keep us both decently, if not luxuriously. He even made enough to employ Mrs Allen, the Dutch-born widow of a local seaman, to cook us one hot meal a day and to keep the house neat. Mrs Allen must have known my secret – though in truth it never seemed as dramatic as that word implies. Just once, I remember, when I was begging to go back to school like other children, she did look me right in the eye. ‘And what about the first time they take your breeches down for the birch? Have you thought about that?’ I dropped my gaze. It was the sort of thing neither Jacob nor I ever thought about directly. But she in her turn never said anything straight out, perhaps from respect for Jacob – ‘such a man of letters’, as she called him, a trifle breathlessly – just as she never said anything about the packed bags he always kept by the door, even after we’d been in England for years and developed a cautious acquaintanceship with the idea of safety. But it may also have been because she, too, was unable to envisage any other solution for me. If I were to be a girl, then I would need to marry, and who would want a girl with neither dowry nor family, with no idea how to sew or to make herself pretty? Looking back now, I’m grateful to Mrs Allen. Looking back, I think of her affectionately. And looking back, I think there might have been mothering there, had I been able to take it. But I was a child who’d learned, the hardest way of all, that safety lay in self-sufficiency.

Still, it was to Mrs Allen I owed the few festivities I knew – the old rites and revels that grow from the blood and bone of this English country, and that made me less of a stranger than I might otherwise have been. It was she who, in the first bright days of February, would take me to the English church to see the procession of candles on Candlemas Day. They didn’t hold with such things at the stricter Dutch church where Jacob took me – ‘Papist nonsense,’ they used to say. It was she who sent me out with other children begging for treats on St Valentine’s Day. ‘It’s one thing we can do right in this household, just like everybody else,’ I heard her say firmly to Jacob, and he stopped protesting and turned away. She took me out into the fields, to look for blossom on the first of May.

Sometimes, too, she’d take me to the playhouse. One of her husband’s cousins was in the business and he’d leave word with the doorman so we could get in for free. Sometimes, after, she’d take me behind the scenes, where the kings and villains became men with traces of grey hair gummed on their face and paint in the corner of their eyes – but still, men whose voices carried across the room, men whose air and gestures made everyone else in the room look paltry. Men in velvets and in lace, even if both were a little shabby. And with them the boys, the shrill-voiced pieces of vanity who’d don petticoats and act women in the play. I looked at those boys with a mixture of fear and the most burning curiosity.

There was one old actor, Ben, who took especial pains with me, showed me the tricks of posture and paint that made young into old and boy into girl – or, I suppose girl into boy. It was only later, as I grew, that I wondered how he had known that these things would interest me. But perhaps he just liked children. Children liked him, certainly. Ben had been to sea, when the acting work would not support him, and he had fabulous stories to tell – of lands where the waves flashed amethyst and turquoise, where emerald green birds with clamouring wings but no legs sucked the honey from scarlet flowers all day, and of the serpent hiss of hard rain beating on a tropical sea. I’d take the stories home to Jacob, like a bartering tool, and sometimes I could sting him into telling me tales of his old life in the south, where bushes of rosemary grew so high they used the branches for firewood, and clouds of pomegranate blossom glowed against a blazing sky.

By and large it was, I suppose, a lonely life, but I didn’t mind much. It was easier that way. As I grew older, I watched the young girls begin to blush and giggle as they filled their dresses, and the young men stare and swagger on their way to the butts, out past the laundresses on Finsbury Fields, and I knew neither was for me. I didn’t go to the butts, though the law said all boys should practise archery; I suppose here as elsewhere our foreignness protected me, explaining any differences away. It was not quite true, I’d found, that the English hated foreigners – not the Londoners, anyhow. What they really hated were those native-born English who were different in any way. For almost ten years, after we first arrived in England, I lived among them as a mouse lives in the wainscoting. Glimpsed, sometimes. Cursed at, occasionally. But on the whole, peaceably.

Winter 1593–94

You could live well here, if you chose to, within a network of others who had fled to Elizabeth’s England, some fleeing the Inquisition’s long arm, others simply to make money. It was easy to forget we were strangers in a strange land. Until something happened to remind you, and anything you’d learned about safety had to be unlearned, painfully.

I must have been turning fifteen when Jacob came home one day, his face bleached.

‘I’ve just seen Roderigo Lopez,’ he said. It was a mark of his anxiety that he was confiding in me. ‘Of course, it’s all an absurdity. But mud sticks, and these days, you never know what nonsense is going to get you into trouble.’

Indeed, that year had been far from easy. First we heard that the Spanish had another Armada on the way – terrifying for everyone, to be sure, but anathema to those who’d seen what the Spanish were doing in the Netherlands, from whence came bloodier stories every day. Next we heard that the winds had changed, and we were safe – certainly through another winter. But then came news that Henry of France, our Protestant hero, had turned Papist as the price of holding on to his country. He said Paris was worth a Mass: he should have heard what they said of him, the grave old men with their neat ruffs and their wine cups, in the Huguenot community. Even the plague had been worse than usual, so that people started talking about the great epidemic thirty years before, when one in four Londoners died. Jacob said the ordinary people, in their ignorance, were blaming ‘strangers’ – immigrants, like us – and keening over the wickedness of the country. Even the playhouses had been closed. But this was something different, apparently.

‘Roderigo should never have got across Lord Essex – never!’ Jacob exclaimed angrily, as I knelt to stoke up the fire. ‘That’s a young man who doesn’t forgive a slight – yes, and a young man in a hurry.’ I was sorry. I didn’t know much about the Earl of Essex, no more than I did of any of the grandees whom the other boys ran after when they rode through the streets, half in admiration and half in mockery. But I liked Dr Lopez, who’d always been kind to me. Jacob said he’d been a Jew once, but he’d become a Christian many years ago when he’d first come to this country from Portugal – ‘Had to, naturally.’ He eyed me with a rare impatience when I looked at him blankly; yes, I knew, of course I did, that no one practised the Jewish faith in this country. But the fact was, I looked at the world around me – the world of people, not of books, or plants – as little as might be.

When Dr Lopez was appointed the senior doctor of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, and even the queen’s own physician, Jacob said, it reflected credit on us all. Showed you could do service to England, even if you were born across the sea. ‘Shows that at least here you can get along, if you’ll just try to fit in and live quietly.’ As a child, all I knew was that, when Dr Lopez came to visit, he brought a bag of comfits for me. And as I grew, and Jacob let me stay up to listen to the grown-ups’ talk, I liked the way his cheeks creased up and his white beard trembled as he banged his beaker on the table so that the drops splashed red, and I liked to hear his stories.

Yes – he had told some about Lord Essex, maybe. Or at any rate a young noble patient who was suffering half from the spleen – ‘If he was a girl, we’d call it hysterics, but he thinks it gives him a hold over her majesty!’ – and half from some unnamed disease, the thought of which made the older men purse their lips slyly.

Perhaps now Jacob thought that it was time the men’s conversations ceased merely to pass over me like a ripple of water. Perhaps he just wanted to talk with somebody.

‘Lord Essex has got wondrous great these last two years. What, not out of his twenties yet, and a privy councillor already. And the favourite companion of the queen’s majesty – aye, and one who dares to slight her and say her nay in a way his father, God rest his soul, would never have done. The old Earl of Leicester, who married Essex’s mother, and brought this boy on as though he’d been his own flesh and blood,’ he explained impatiently. ‘Myself, I think that’s why the queen keeps him so close, for the old lord’s sake, but of course there are those who say –’

Mrs Allen came in then, so I didn’t hear what others say, though naturally I could guess. It sounded silly to me – the earl was in his twenties, after all, and the queen must be more than sixty. I didn’t hear, then, what Dr Lopez had done to annoy Lord Essex, except maybe talk too freely. But I was of an age by now to pick up scraps of information when anything interested me.

Advent didn’t bring us many callers – who sent out invitations to dine, when you had four weeks of fast days? – but when visitors did come on business I kept my ears open. I learnt that Lord Essex was white hot against the Spaniards, and anxious to lead an army off to war and make his fame that way. I learnt it was the Cecils, old Lord Burghley and his son, who were leaders of the peace party, and the queen, reluctant to spend blood or money, leaned their way in terms of policy. And that Lord Essex, pent up at home, was seeing Spanish spies under every bush, and claimed Dr Lopez – our Dr Lopez – had given house-room to Spaniards, or men in Spanish pay, plotting some dangerous conspiracy. Then Christmas came, and the feasting and the frost fair, and I forgot it all for the moment.

Christmas wasn’t out when Dr Lopez was arrested. It was only the first of January, and the news spread like a sickness from feasting house to feasting house, quenching each little light of merriment as surely as if it had been touched by the plague, and as swiftly.

‘They’ve taken him to Essex House. But Lord Burghley and his son – you know, Robert Cecil, the hunchbacked one – have been sharing the interrogation. They’re reasonable men, the Cecils. He’ll be out before Twelfth Night, you’ll see.’ It was our most cheerful neighbour, a dapper tailor once from Le Havre. Jacob glanced at him sourly.

‘Reasonable men, you say. Are reasonable men going to fight with Essex over the welfare of a foreigner, and a Jew at that? What have they found to charge him with, anyway?’

It was three days later when we heard. For two of those days Lord Essex had sulked – the Cecils had done the right thing, after all, they’d declared Lopez innocent, and the queen had believed them, to the earl’s fury – but on the third he had been busy. Lopez had been whisked into the Tower, and the earl set about declaring, beyond all doubt, a treasonable conspiracy, a Spanish plot to poison the queen, as her doctor could do so easily.

Terrified and confused, Lopez himself seemed half to agree. (‘Of course he agreed! They showed him the rack,’ said Jacob indignantly. I saw one of the other men there, another foreigner, rub his shoulder as if an old wound pained him, and stir uneasily.) Lopez had actually agreed he’d once taken Spanish pay, but only on the instructions of English agents, to lead King Philip astray. But that was back in the days of Walsingham, the old spymaster, and now Walsingham was gone, and couldn’t say yea or nay.

‘Take heed of that,’ Jacob said. ‘It’s hard enough not to get caught up in intrigue, if you’re a foreigner in this country. But the men who try to hire you will leave you in the lurch – by dying, if they can’t do it any other way.’ Privately he told me he had not the least hope; something about a job Lord Essex wanted for a friend of his, and the queen had given it to someone else, on Cecil advice, so that she’d want to soothe Lord Essex by yielding to him in some other way.

After the doctor and his associates were arraigned and sentenced, the little tailor took some comfort in the fact that the queen couldn’t bring herself to sign the death warrant at once.

‘She knows it’s wrong, she’ll let them out eventually.’

‘She knew it was wrong with her cousin, the Scots queen, but she still signed. Eventually –’ Jacob imitated the little tailor. ‘She’s the queen, isn’t she?’

When the news came that she had signed, he grew ever more gloomy. Lopez was to be tried and hanged, he said, on Tyburn tree. It was from the streets that I heard the full story.

‘Hanged all right, but not till he’s dead, or not unless he’s very lucky. Then they’ll cut him down alive and hack off his privities, and slit open his belly and pull his guts out before his eyes.’ One lad with a lazy eye seemed to know all about it. ‘Sometimes, if they like him, the crowd yell to the executioners to leave it, to let the man die first, at the end of the rope, but they won’t do that for a Christ-killer, you’ll see.’

‘Anyway,’ another boy chimed in, ‘they say Jews are built differently.’

The night before, Jacob told me he was going to watch. ‘I have to, the Lord knows why. Somewhere in that howling crowd, there has to be a friendly eye. But you’re to stay home – do you hear me?’

I nodded, my eyes fixed on my plate. In the last weeks, the dream had been coming back to me. It wasn’t of the knife, or the hilt in the belly, not precisely. It was the running, and the knowing that I couldn’t run fast enough, and that they were going to die because of me. The next morning, I pretended to be asleep as I heard Jacob leave. In his absence I tidied his desk, and cleaned out his inkwell. I was going to sharpen him some quills, but the knife disturbed me. Instead I set myself to copying the various pages of figures he had left me – for I helped him in his paid work by now – and tried not to count the time passing slowly. In the end, the suspense got to me – and the curiosity. I had to know. I had to see.

I left the house as quietly as a mouse leaves its hole with a cat there to pounce and, slipping surreptitiously from corner to corner, made my way towards Newgate, where the Holborn road leads west. It was one of those days, again, when everything seemed to move slowly. When each familiar sight of the streets struck me with unusual clarity. I suppose everyone in London can’t really have gone to see the sight, but that’s how it felt to me. As though I were a ghost – one of those spectres they used to paint for the casting down into Hell, mouth ever open in a silent scream – moving through an empty city. I saw Master de l’Obel, his face full of distress, but he did not see me.

Past the looming bulk of Ely Place, past the great chains across the road, to seal the way to the City when necessary, and soon I was in open country. In this dank weather the fields were just a sludgy mass of brown, cold and uninviting. Starting out so late, I was far behind the mass of the crowd, but the state of the track showed how many had gone before me.

I hadn’t realised it was such a distance. I’d been hurrying my steps, to try to catch up, and I’m not sure what it was that halted me. Maybe the smell brought back on the wind, or the sick low roar of the people pressing westwards ahead of me. I don’t really know what it was – the fire must have smelled like any other, even if they had lit it to burn the doctor’s privates, and the crowd was noisier for the football match every Accession Day. Maybe, as I started to find myself among squabbling families, and carts full of people as cheery as on market day, it was the look I saw on the faces of those others who were flocking that way.

In the end I never even reached Tyburn. Just as well, maybe. I heard later that Dr Lopez died shouting out that he loved her majesty better than Christ, and that one of the men who died with him tried to fight off the executioner, and they had to hold him down to slash his belly open. Up until now, I’d only half understood things Jacob tried to teach me – about quarrel, and dispute, and the passion of belief. About how it made men do things in God’s name that in fact the Creator would weep to see. I hadn’t understood why – when Mrs Allen nagged him into getting me ordinary school books – he’d snatched the discourse on rhetoric back at once, having caught me showing off for her admiring eyes, imitating the kind of rhetoric class real schoolboys had every day. At the time, I felt reproved for my vanity, but later I came to understand more clearly what Jacob had muttered under his breath about convincing and convicting, and about the wrong-headedness of teaching children that the important thing in the world was to prove their point, however blunted it might be.

Now I did understand, as I saw citizens’ kindly faces alight with a brutal glee. I stood there in the muddy track for a moment, cursing myself for folly. Then I turned back, and half ran towards the familiar streets. At the empty house I bent over the desk, trying to ignore the chill sickness inside, and took care not to look up when Jacob returned, his tread slower and heavier than when he had gone away.

I had other things to concern me, as I grew older. In my mind and in Jacob’s I was a boy, but my growing body heard a different story. Quietly, as she sat with our mending by the fire, Mrs Allen had made sure I’d know what I needed to know, though always imparting her information with the casual air of one who is talking for the sake of it. Never as if these were things that I might need to know personally. By the time I first bled I knew what to expect, though the pain like a knife grinding in my belly brought the dreams worse than usual, and I was glad that I did not bleed frequently. And that my shape stayed thin and unformed – slim enough in a stripling, but what in a girl you might have called scrawny.

Autumn 1595, Accession Day

Sometimes, when Jacob was out, I’d slip on my cloak and go down to the Thames, and wish the waters could take me … somewhere. To some other destiny. I heard Mrs Allen telling Jacob, in that comfortable way, that all young people were sometimes as wild as March hares, and I suppose it was true.

If I’d been of another disposition, it might have taken me to the bear-baitings, or the executions. If I’d been a proper girl it might have taken me to a boy’s arms. If I’d really been that boy, it might have taken me to the stews. As it was, it took me towards the court, for the jousts on Accession Day. Ascension Day, I almost said, when in the days of the old faith they celebrated the Virgin Mary. But now the altars and the blue robed, sweet-faced statues were gone. We celebrated another virgin queen, and after more than three and a half decades on the throne, in truth she seemed as much a fixture in the sky.

The tiltyard lay to the northwards of most of the palace buildings, though close enough that you could see its yawning doorways, close enough you could feel the beast’s hot breath down your neck. Close enough that the turrets and pennants loom like a fairy-tale castle. Other children heard fairy tales as something delightful, sweet as sugar comfits, but to me they were always frightening, with their world of things that were not as they seemed, of unknown possibilities. I knew you went to the tilt-yard not just for the fights, but for the masques and pageants and stories they used to dress up the fact that times had changed, and knights no longer really fought each other with spear-tipped poles under codes of chivalry. I was scathing of all that; the very young feel scathing easily.

This – I told myself, as I jostled along with the crowd trying to get in at the gates, squeezed by a merchant’s wife with a picnic basket on one side, and on the other by a courting couple who couldn’t even keep their hands off each other until they found a seat – was modern London, where you could buy anything from a Spanish orange tree to a copy of an Italian play, where every householder had by law to hang a light outside, so that the night streets were almost bright like day. Where the queen’s own godson had invented a flushing jakes, so that after you’d evacuated, a stream of water carried your filth away … But it was good, just for the moment, to be swept along with the crowd. To smell the damp sand of the arena, and the farmyard aroma of the horse lines, where the chargers were shitting with eagerness and fear.

The only place I could get was high up in the grandstand, so that what was going on below had an air of unreality, like something seen at the play. But I was happy enough to gaze down at the courtiers who were coming in last of all, to the seats beside the arena, furred and cloaked against the November air. Mulberry and tawny, sulphur yellow and ox-blood red, their very velvets seemed to warm the day.

At one end, the royal gallery still stood empty, fluttering with silks in the Tudor colours, green and white. The crowds were beginning to cheer some arrivals – clearly well-known personalities. The man beside me, a burgher as broad as he was tall, could see my ignorance, and was only too happy to enlighten me.

‘That’s Ralegh,’ he said, ‘see, the tall one? That’s the queen’s cousin, well, kinsman, Lord Howard the Lord Admiral, with the white beard. Look, that’s Master Cecil, Lord Burghley’s son – I daresay the old man will stay away, I doubt he’s got much taste now for a tourney. But Robert Cecil, he’s a rising man – and a sharp one, they say.’ There were no cheers for Robert Cecil, I noticed. In fact there were even some jeers as he took his place. He was a small man, I saw, and almost twisted – hunch-backed? – in some way, though for all that he managed his slight dark figure gracefully.

‘Ah,’ my neighbour said on a grunt of satisfaction, ‘here she comes, the queen’s majesty.’ Now there really was cheering. I peered downwards, hungrily. I hadn’t expected to make anything out, but as the stiff tiny mannequin advanced to show herself, I found I could see quite clearly. See where the blaze of jewels caught the winter sunlight, see the bright red fringe of curls around the white oval of her face. Around her clustered the young maids of honour, with one or two older ladies.

Jacob and his friends, talking of an evening, had nothing but contempt for the court – a nest of carrion crows grown fat, they said, of maggots feasting on decay. But even they would hush their wives when any of the talk – ‘Of course it’s a wig. My sister’s husband’s a perruquier, and he says she’s bald as an egg underneath!’ – came close to touching the queen’s dignity.

‘She may have her vanities as a woman,’ they’d say, ‘and why shouldn’t she? But she’s given us close on four decades of quiet – aye, I know things haven’t been so good this last year or two, but she can’t help the weather and the harvest, can she? Just look across the Channel if you want to see how bad things could be.’ And then they’d break off, with a sidelong glance at Jacob, and at me.

Something was happening, down in the lists. A herald on horseback, dressed in red and white, had trotted into the arena, and was making the circuit of its brightly painted wooden walls with something in his hand held high.