Полная версия

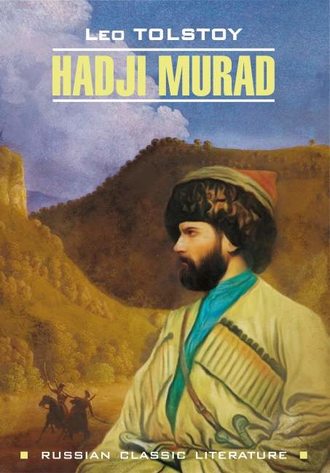

Hadji Murad / Хаджи-Мурат. Книга для чтения на английском языке

But when Poltoratsky and his company came up he nevertheles gave orders to fire, and scarcely had the word been passed than along the whole line of sharpshooters the incessant, merry, stirring rattle of our rifles began, acompanied by pretty dissolving cloudlets of smoke. The soldiers, pleased to have some distraction, hastened to load and fired shot after shot. The Chechens evidently caught the feeling of excitement, and leaping forward one after another fired a few shots at our men. One of these shots wounded a soldier. It was the same Avdeev who had lain in ambush the night before.

When his comrades approached him he was lying prone, holding his wounded stomach with both hands, and rocking himself with a rhythmic motion moaned softly. He belonged to Poltoratsky’s company, and Poltoratsky, seeing a group of soldiers collected, rode up to them.

“What is it, lad? Been hit?” said Poltoratsky. “Where?”

Avdeev did not answer.

“I was just going to load, your honor, when I heard a click,” said a soldier who had been with Avdeef; “and I look and see he’s dropped his gun.”

“Tut, tut, tut!” Poltoratsky clicked his tongue. “Does it hurt much, Avdeev?”

“It doesn’t hurt but it stops me walking. A dropu of vodka now, your honor!”

Some vodka (or rather the spirit drunk by the soldiers in the Caucasus) was found, and Panov, severely frowning, brought Avdeev a can-lid full. Avdeev tried to drink it but immediately handed back the lid.

“My soul truns against it,” he said. “Drink it yourself.”

Panov drank up the spirit.

Avdeev raised himself but sank back at once. They spread out a cloak and laid him on it.

“Your honor, the colonel is coming,” said the sergeant-major to Poltoratsky.

“All right. then will you see to him?” said Poltoratsky, and flourishing his whip he rode at a fast trot to meet Vorontsov.

Vorontsov was riding his thoroughbred English chestnut gelding, and was accompanied by the adjutant, a Cossack, and a Chechen interpreter.

“What’s happening here?” asked Vorontsov.

“Why, a skirmishing party attacked our advanced line,” Poltoratsky answered.

“Come, come – you arranged the whole thing yourself!”

“Oh no, Prince, not I,” said Poltoratsky with a smile; “they pushed forward of their own accord.”

“I hear a soldier has been wounded?”

“Yes, it’s a great pity. He’s a good soldier.”

“Seriously?”

“Seriously, I believe … in the stomach.”

“And do you know where I am going?” vorontsov asked.

“I don’t.”

“Can’t you guess?”

“No.”

“Hadji Murad has surrendered and we are now going to meet him.”

“You don’t mean to say so?”

“His envoy came to me yesterday,” said Vorontsov, with difficulty repressing a smile of pleasure. “He will be waiting for me at the Shalin glade in a few minutes. Place sharpshooters as far as the glade, and then come and join me.”

“I understand,” said Poltoratsky, lifting his hand to his cap, and rode back to his company. He led the sharp shooters to the right himself, and ordered the seargeant-major to do the same on the left side.

The wounded Avdeev had meanwhile been taken back to the fort by some of the soldiers.

On his way back to rejoin vorontsov, Poltoratsky noticed behind him several horsemen who were overtaking him. In front on a white-maned horse rode a man of imposing appearance. He wore a turban and carried weapons with gold ornaments. This man was Hadji Murad. He approached Poltoratsky and said something to him in Tartar. Raising his eyebrows, Poltoratsky made a gesture with his arms to show that he did not understand, and smiled. Hadji Murad gave him smile for smile, and that smile struck Poltoratsky by its childlike kindliness. Poltoratsky had never expected to see the terrible mountain chief look like that. He had expected to see a morose, hard-featured man, and here was a vivacious person whose smile was so kindly that Poltoratsky felt as if he were an old acquaintance. He had only one peculiarity: his eyes, set wide apart, which gazed from under their black brows calmly, attentively, and penetratingly into the eyes of others.

Hadji Murad’s suit consisted of five men, among them was Khan Mahoma, who had been to see Prince Vorontsov that night. He was a rosy, round-faced fellow with black lashless eyes and a beaming expression, full of the joy of life. Then there was the Avar Khanefi, a thick-set, hairy man, whose eyebrows met. He was in charge of all Hadji Murad’s property and led a stud-bred horse which carried tightly packed saddle bags. Two men of the suite were particularly striking. The first was a Lesghian: a youth, broad-shouldered but with a waist as slim as a woman’s, beautiful ram-like eyes, and the beginnings of a brown beard. This was Eldar. The other, Gamzalo, was a Chechen with a short red beard and no eyebrows or eyelashes; he was blind in one eye and had a scar across his nose and face. Poltoratsky pointed out Vorontsov, who had just appeared on the road. Hadji Murad rode to meet him, and putting his right hand on his heart said something in Tartar and stopped. The Chechen interpreter translated.

“He says, I surrender myself to the will of the Russian Tsar. I wish to serve him,’ he says. I wished to so do long ago but Shamil would not let me.’”

Having heard what the interpreter said, Vorontsov stretched out his hand in its wash-leather glove to Hadji Murad. Hadji Murad looked at it hestitatingly for a moment and then pressed it firmly, again saying something and looking first at the interpreter and then at Vorontsov.

“He says he did not wish to surrender to any one but you, as you are the son of the Sirdar and he respects you much.”

Vorontsov nodded to express his thanks. Hadji Murad again said something, pointing to his suite.

“He says that these men, his henchmen, will serve the Russians as well as he.”

Vorontsov turned towards then and nodded to them too. The merry, black-eyed, lashless Chechen, Khan Mahoma, also nodded and said something which was probably amusing, for the hairy Avar drew his lips into a smile, showing his ivory-white teeth. But the red-haired Gamzalo’s one red eye just glanced at Vorontsov and then was again fixed on the ears of his horse.

When Vorontsov and Hadji Murad with their retinues rode back to the fort the soldiers released form the lines gathered in groups and made their own comments.

“What a lot of men that damned fellow has destroyed! And now see what a fuss they will make of him!”

“Naturally. He was Shamil’s right hand, and now – no fear!”

“Still there’s no denying it! he’s a fine fellow – a regular djhigit11!”

“And the red one! He squints at you like a beast!”

“Ugh! He must be a hound!”

They had all specially noticed the red one. Where the wood-felling was going on the soldiers nearest to the road ran out to look. Their officer shouted to them, but Vorontsov stopped him.

“Let them have a look at their old friend.”

“You know who that is?” he added, turning to the nearest soldier, and speaking the words slowly with his English accent.

“No, your Excellency.”

“Hadji Murad… . Heard of him?”

“How could we help it, your Excellency? We’ve beaten him many a time!”

“Yes, and we’ve had it hot from him too.”

“Yes, that’s true, your Excellency,” answered the soldier, pleased to be talking with his chief.

Hadji Murad understood that they were speaking about him, and smiled brightly with his eyes.

Vornotsov returned to the fort in a very cheerful mood.

Chapter VI

Young Vorontsov was much pleased that it was he, and no one else, who had succeeded in winning over and receiving Hadji Murad – next to Shamil Russia’s chief and most active enemy. There was only one unpleasant thing about it: General Meller-Zakomelsky was in command of the army at Vozdvizhenski, and the whole affair ought to have been carried out through him. As Vorontsov had done everything himself without reporting it there might be some unpleasantness, and this thought rather interfered with his satisfaction. On reaching his house he entrusted Hadji Murad’s henchmen to the regimental adjutant and himself showed Hadji Murad into the house.

Princess Marya Vasilevna, elegantly dressed and smiling, and her little son, a handsome curly-headed child of six, met Hadji Murad in the drawing room. The latter placed his hands on his heart, and through the interpreter – who had entered with him – said with solemnity that he regarded himself as the prince’s kunak, since the prince had brought him into his own house; and that a kunak’s whole family was as sacred as the kunak himself.

Hadji Murad’s appearance and manners pleased Marya Vasilevna, and the fact that he flushed when she held out her large white hand to him inclined her still more in his favor. She invited him to sit down, and having asked him whether he drank coffee, had some served. He, however, declined it when it came. He understood a little Russian but could not speak it. When something was said which he could not understand he smiled, and his smile pleased Marya Vasilevna just as it had pleased Poltoratsky. The curly-haired, keen-eyed little boy (whom his mother called Bulka) standing beside her did not take his eyes off Hadji Murad, whom he had always heard spoken of as a great warrior.

Leaving Hadji Murad with his wife, Vorontsov went to his office to do what was necessary about reporting the fact of Hadji Murad’s having cove over to the Russians. When he had written a report to the general in command of the left flank – General Kozlovsky – at Grozny, and a letter to his father, Vorontsov hurried home, afraid that his wife might be vexed with him for forcing on her this terrible stranger, who had to be treated in such a way that he should not take offense, and yet not too kindly. But his fears were needless. Hadji Murad was sitting in an armchair with little Bulka, Vorontsov’s stepson, on his knee, and with bent head was listening attentively to the interpreter who was translating to him the words of the laughing marya Vasilevna. Marya Vasilevna was telling him that if every time a kunak admired anything of his he made him a present of it, he would soon have to go about like Adam… .

When the prince entered, Hadji Murad rose at once and, surprising and offending Bulka by putting him off his knee, changed the playful expression of his face to a stern and serious one. He only sat down again when Vorontsov had himself taken a seat.

Continuing the conversation he answered Marya Vasilevna by telling her that it was a law among his people that anything your kunak admired must be presented to him.

“Thy son, kunak?” he said in Russian, patting the curly head of the boy who had again climbed on his knee.

“He is delightful, your brigand!” said Marya Vasilevna to her husband in french. “Bulka has been admiring his dagger, and he has given it to him.”

Bulka showed the dagger to his father. “C’est un objet de prix!12” added she.

“Il faudra trouver l’occasion de lui faire cadeau13,” said Vorontsov.

Hadji Murad, his eyes turned down, sat stroking the boy’s curly hair and saying: “Djhigit, djhigit!”

“A beautiful, beautiful dagger,” said Vorontsov, half drawing out the sharpened blade which had a ridge down the center. “I thank thee!”

“Ask him what I can do for him,” he said to the interpreter.

The interpreter translated, and Hadji Murad at once replied that he wanted nothing but that he begged to be taken to a place where he could say his prayers.

Vorontsov called his valet and told him to do what Hadji Murad desired.

As soon as Hadji Murad was alone in the room allotted to him his face altered. The pleased expression, now kindly and now stately, vanished, and a look of anxiety showed itself. Vorontsov had received him far better than Hadji Murad had expected. But the better the reception the less did Hadji Murad trust Vorontsov and his officers. He feared everything: that he might be seized, chained, and sent to Siberia, or simply killed; and therefore he was on his guard. He asked Eldar, when the latter entered his room, where his murids had been put and whether their arms had been taken from them, and where the horses were. Eldar reported that the horses were in the prince’s stables; that the men had been placed in a barn; that they retained their arms, and that the interpreter was giving them food and tea.

Hadji Murad shook his head in doubt, and after undressing said his prayers and told Eldar to bring him his silver dagger. He then dressed, and having fastened his belt, sat down on the divan with his legs tucked under him, to await what might befall him.

At four in the afternoon the interpreter came to call him to dine with the prince.

At dinner he hardly ate anything except some pilau14, to which he helped himself from the very part of the dish from which Marya Vasilevna had helped herself.

“He is afraid we shall poison him,” Marya Vasilevna remarked to her husband. “He has helped himself from the place where I took my helping.” Then instantly turning to Hadji Murad she asked him through the interpreter when he would pray again. Hadji Murad lifted five fingers and pointed to the sun. “Then it will soon be time,” and Vorontsov drew out his watch and pressed a spring. The watch struck four and one quarter. This evidently surprised Hadji Murad, and he asked to hear it again and to be allowed to look at the watch.

“Voila l’occasion! Donnez-lui la montre,” said the princess to her husband.

Vorontsov at once offered the watch to Hadji Murad.

The latter placed his hand on his breast and took the watch. He touched the spring several times, listened, and nodded his head approvingly.

After dinner, Meller-Zakomelsky’s aide-de-camp was announced.

The aide-de-camp informed the prince that the general, having heard of Hadji Murad’s arrival, was highly displeased that this had not been reported to him, and required Hadji Murad to be brought to him without delay. Vorontsov replied that the general’s command should be obeyed, and through the interpreter informed Hadji Murad of these orders and asked him to go to Meller with him.

When Marya Vasilevna heard what the aide-decamp had come about, she at once understood that unpleasantness might arise between her husband and the general, and in spite of all her husband’s attempts to dissuade her, decided to go with him and Hadji Murad.

“Vous feriez bien mieux de rester – c’est mon affaire, non pas la vôtre… .”15

“Vous ne pouvez pas m’empecher d’aller voir madame la générale!”16

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

1

aoul – a Tatar village

2

kizyak – a fuel made of straw and manure

3

saklya – a Caucasian house, clay-plastered and often built of earth

4

naib – a Tatar lieutenant or governor

5

murid – a disciple or follower: “One who desires” to find the way in Muridism. Muridism Almost identical with Sufism.

6

burka – a long round felt cape

7

beshmet – a Tatar undergarment with sleeves

8

yok – no, not

9

kunak – a sworn friend, an adopted brother

10

“Eh bien! vous allez me dire ce que c’est.” – Well! You tell me what it is.

“Mais, ma chère …” – But, my dear…

“Pas de ma chère ! C’etait un emissaire, n’est-ce pas?” – Don’t my dear me! He was an emissary, was he not?

“Quand même, je ne puis pas vous le dire.” – Even so, I can not tell you.

“Vous ne pouvez pas? Alors, c’est moi qui vais vous le dire!” – You can not? So I'll tell you!

“Vous?” – You?

11

djhigit – the same as a brave among American Indians, but the word is inseparably connected with the idea of skilful horsemanship

12

C’est un objet de prix! – It is an item of value!

13

Il faudra trouver l’occasion de lui faire cadeau – We will have to find an opportunity to make him a gift.

14

pilau – an oriental dish prepared with rice and mutton or chicken

15

Vous feriez bien mieux de rester – c’est mon affaire, non pas la vôtre… – You’d better stay – it’s my business, not yours…

16

Vous ne pouvez pas m’empecher d’aller voir madame la générale! – You can not prevent me from going to see Madam General!