Полная версия

Her Cheyenne Warrior

“Where is it?” she shouted. “I need it so no man can get within three feet of me. No man. Including you!”

He took a step closer.

“Don’t!” she shouted, backing up. “Don’t come any nearer.”

Being filled with fear was more dangerous than being filled with anger. That went for people as well as animals. Black Horse held his arms out to his sides as he would while approaching a cornered horse. “No one will hurt you, Poeso,” he said quietly.

“I know they won’t,” she shouted. “I won’t let them! I won’t let anyone hurt me ever again!”

The way she shook entered his heart, made it pound with an unknown anger. She had been mistreated, badly, at some time, someplace. “I won’t let them either,” he whispered.

“I won’t let you hurt me.”

“I will not hurt you,” he said. “I will protect you. I will stop all others.”

Author Note

Black Horse and Lorna’s story came to me as an image of a young woman stripped down to her underclothes, standing in the middle of a river surrounded by Cheyenne warriors. At the time I was in the midst of writing Saving Marina, and didn’t have the time to fully embrace a new story. But I found a few novels about the Cheyenne.

Most writers—I’m assuming—are also avid readers, and years ago I formed the habit of reading every night. Sometimes it’s just a chapter or two—other times I’ll stay up half the night to finish a book that I just can’t put down. Therefore, even after spending hours writing about the Salem Witch Trials, when I went to bed I’d read about the peaceful Northern Cheyenne.

I must say those two cultures merging as I fell into sleep produced some peculiar dreams!

Such is the inner world of a writer. Our imaginations just don’t know how to rest!

I sincerely hope you enjoy spending some time in Wyoming as Lorna discovers Black Horse is, indeed, Her Cheyenne Warrior.

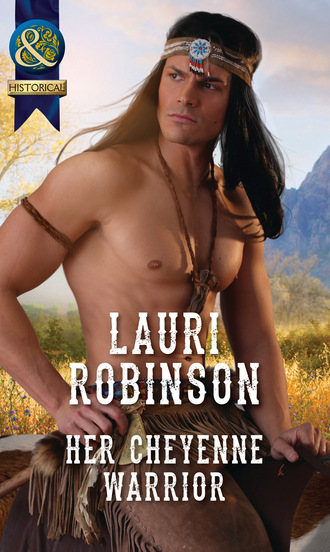

Her Cheyenne Warrior

Lauri Robinson

www.millsandboon.co.uk

A lover of fairytales and cowboy boots, LAURI ROBINSON can’t imagine a better profession than penning happily-ever-after stories about men—and women—who pull on a pair of boots before riding off into the sunset … or kick them off for other reasons. Lauri and her husband raised three sons in their rural Minnesota home, and are now getting their just rewards by spoiling their grandchildren. Visit: laurirobinson.blogspot.com, Facebook.com/lauri.robinson1, or Twitter.com/LauriR.

MILLS & BOON

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

SIGN ME UP!

Or simply visit

signup.millsandboon.co.uk

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

To my brother Jeff.

Finally.

Love you.

Contents

Cover

Introduction

Author Note

Title Page

About the Author

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Epilogue

Extract

Copyright

Prologue

January 1864, Land of the Northern Cheyenne

The gathering brought leaders from bands near and far, despite the snow-covered grounds and days of short light. For some the journey had been long and difficult, but the attacks against many tribes on land to the south and east had required the tribal council to join together. The harmony and peace that the Tsitsistas—The People—sought and held in high regard was once again being challenged. Not just by the white men, but by younger members of the bands.

Black Horse listened with intent as both the elder and the younger chiefs spoke of conflicts with the white men, of sweeping illnesses and attacks that affected not only the Cheyenne, but threatened bands of all the Nations. Chosen by members of this council eight years ago to be the leader of The Horse Band, Black Horse was known for his slow-to-rise temper. He did not rile easy, but when he did, he was a fierce warrior whom few dared oppose, which meant that his opinions were respected and sought after. But on this day he could not deny the shift in attitudes of many of the leaders. Several Great Chiefs, those of the older generation, were absent; they had departed this earth, some killed in attacks, others dead from the white man’s illnesses. The younger generation that had replaced them were not following the traditional path of advocating for peace.

Several of the these leaders wore war shirts made of deerskin and decorated with hammered silver coins taken from white men, and they demanded revenge with a ferocity more in line with the Southern Cheyenne than the northern bands. Black Horse was of the younger generation but he was not a new leader, and his values had been learned from those who had come before him. His heart and soul and his vision had been challenged by the white man, and at times still weighed heavy inside him, despite his commitment to peace.

While the smoking pipe was passed around the circle, he listened through the long hours of arguments and suggestions. Although he could understand the anger and frustration of those demanding more direct action, his overall view remained unaltered. Believing that the best plan for prosperity was to remain steadfast to the way of life The People had always known, Black Horse chose his words wisely.

“Tsitsistas,” he started slowly, while nodding to include each leader sitting around the large circle, “are of small number because we know that Mother Earth can only host so many of her children. Just as the grass can only feed a specific number of buffalo, elk and deer. If there are too many of any one kind, some will starve, die, until Mother Earth can rebalance the numbers again. We do not know this number, only Mother Earth has this knowledge, but Tsitsistas should remain small in number so all can eat rather than see some starve.”

“Too many Tsitsistas have died,” Otter Hair argued. “The white man’s sickness and the battles they rage have made our number even smaller. Soon we will disappear. This is the white man’s wish, and we must stop them before none are left.”

There were times when looking another directly in the eye was considered bad manners, but not when disciplining. Black Horse leveled a glare upon Otter Hair—named for the strips of otter fur braided into his hair—until the other leader dipped his chin, acknowledging that Black Horse had not given permission for another to speak. He would not rise to anger during a tribal council, but neither would he tolerate misbehavior. To interrupt another was always bad manners and never allowed.

He held silent long enough for all to understand his displeasure with Otter Hair before saying, “The death of every Cheyenne, of every brother, every sister, is felt across our land, but we cannot let the pain cloud our vision. It is our duty, that of each chief in this council, to see Tsitsistas survive. To assure every member of our band is fed and taken care of, and to assure the next generation has much land with plentiful food. This cannot happen when all we discuss is battles with the white man. We must talk of the hunting season and health of our people. The white man is not our concern.”

He paused in order to draw on the pipe that had once again reached him and let others consider the truth behind his words. He also used the time to attempt to settle the stirring inside him. It was difficult to strive for peace while a sense of injustice infiltrated Cheyenne land. Inside, where he tried not to look, he saw changes and knew that more were coming. He also knew that Maheo—The Great Creator—would show him what must be done when the time was right.

Passing the pipe to Silver Bear, Black Horse added, “The white men continue to fight each other where the sun rises. They do not care about future generations and will kill many of their own kind without help from Tsitsistas. When their war is over, the Apache, the Comanche and our southern brothers who decorate their clothes and horses with the scalps of white men will attack the survivors. We will council again then, if our help is needed.”

Chapter One

July 1864, Nebraska Territory

If a year ago someone had told her she’d be a part of a misfit band of women, wearing the same ugly black dress every day, and have calluses—yes, calluses—on her hands, she’d have laughed in their face. Then again, a year ago she’d had no reason to believe her birthday would be any different than the nineteen previous ones had been, complete with a party where friends plied her with frivolous gifts of stationery, silly doodads and fans made of colorful ostrich feathers.

Lorna Bradford lifted her stubby pencil off the page of her tattered diary where she’d written Tomorrow is my birthday, and questioned scribbling out the words. It wasn’t as if there would be a celebration, and she certainly didn’t need a reminder of what had happened last year. That night was the catalyst that had brought her here, to a land and a way of life that was entirely foreign to her. But somehow, though she had once been a stranger to it, she had begun to grow used to this life, this land, and to feel at home, as amazing as that seemed.

Wearing the same dress day after day didn’t faze her as much as it once would have; and the calluses on her hands meant she no longer needed to doctor the blisters she’d suffered from during the first few weeks holding the reins of the mules.

Nibbling on the flat end of the pencil, Lorna scanned the campsite she and the others had created for the night. Stars were already starting to appear. Soon it would be too dark to write in her diary. Maybe that was just as well. She had nothing to add. It had been an uneventful day. God willing, tomorrow would be no different.

Lorna pulled the pencil away from her lips and twirled it between her thumb and fingers. She made a note of some sort every night, and felt compelled to do so again. Perhaps because it was habit or maybe because it marked that she’d lived through another day. Despite the past. Despite the odds. Despite the obstacles.

In fact, her notations were proof they were all still alive, and that in itself said something. The four of them might be misfits in some senses of the word, but they were resilient and determined.

Meg O’Brien was most definitely determined. She was over near the fire, brushing her long black hair. Something she did every night. The care she gave her hair seemed odd considering it was covered all day and night by the heavy nun’s habit. Then again, the nun’s outfits had been Meg’s idea, and the disguises had worked for the most part. Soon Meg would plait her hair into a single braid and cover it with the black cloth, a sign her musing was over for the evening. Though boisterous and opinionated, Meg sat by herself for a spell each night. Lorna wondered what Meg thought about when she sat there, brushing her hair and staring into the fire, but never asked. Just as Meg never asked what Lorna wrote about in her diary each night.

Lorna figured Meg had a lot of secrets she didn’t want anyone to know about, and could accept that. After all, they all had secrets. Her own were the reason she was in the middle of Nebraska with this misfit band.

She and Meg had met in Missouri, when Meg had answered Lorna’s advertisement seeking passage on a wagon train. The railroad didn’t go all the way to California. A stagecoach had been her original plan, but the exorbitant cost of traveling on a stage all the way to California was well beyond her financial resources, thus joining a wagon train had become her only choice. When she’d answered the knock on her hotel room door, Meg had barreled into the room asking, “You trying to get yourself killed?”

Lorna had pulled her advertisement right after Meg had explained that wagon trains heading west had slowed considerably since the country was at war and that Lorna would not want to be associated with the ones who would respond to her advertisement. Meg had been right, and Lorna would be forever grateful to her. They’d formed a fast friendship that very first meeting, even though they had absolutely nothing in common.

The clink and clatter coming from inside the wagon, against which Lorna was leaning, said Betty Wren was still fluttering about, rearranging the pots and pans they’d used for the evening meal. Betty liked things neat and orderly and knew at any given moment precisely where every last item of their meager possessions and supplies was located. Too bad she hadn’t known where that nest of ground bees had been. Perhaps then her husband, Christopher, wouldn’t have stepped on it.

The wagon train had only been a week out of Missouri, and Christopher had been their first fatality. He’d died within an hour of stepping on that bee’s nest. Others had been stung as well, but none like him. Lorna had never seen a body swell like Christopher’s had. A truly unidentifiable corpse had been buried in that grave. She’d never seen a woman more brokenhearted than Betty, either, and was glad that Betty only cried occasionally these days.

Betty’s heart was healing.

They eventually did. Hearts, that was. They healed. Whether a person wanted them to or not. Even hate faded. That was something she hadn’t known a year ago. A tightening in Lorna’s chest had her glancing back down at the notation in her diary. The desire for retribution, she had discovered, grew stronger with each day that passed.

“Can’t think of anything to write about?”

That was the final member of their group speaking, Tillie Smith. She, too, had lost her husband shortly after the trip started, while crossing a river. The water wasn’t deep, but Adam Smith had been trapped beneath the back wheel of his wagon, and it was too late by the time the others had got the wagon off him. Trapped on his back, he’d drowned in less than two feet of water. It had been a terrifying and tragic event.

“I guess not,” Lorna answered, shifting to look at Tillie, who was under the wagon and wrapped in a blanket. More to keep the bugs from biting than for warmth. The heat of the days barely eased when the sun went down, but the bugs came out, and they were always hungry. How they managed to bite through the heavy black material of the nun outfits was astonishing.

“You could write that I say I’m sorry,” Tillie said.

“I will not,” Lorna insisted. “You have nothing to be sorry about.”

Tillie wiggled her small frame from under the wagon, pulling the blanket behind her. Once sitting next to Lorna with her back against the same wheel, she wrapped the blanket around her shoulders. “Yes, I do. If not for me, the rest of you would still be with the wagon train. You should have left me behind.”

Lorna set her pencil in her diary, and closed the book. After the death of her husband, pregnant Tillie had started to hemorrhage. The doctor traveling on the train—a disgusting little man who never washed his hands—said nothing could be done for her. In great disagreement, Lorna and Meg, as well as Betty, who’d latched on to her and Meg for protection as well as friendship by that time, had chosen to take matters into their own hands. The small town they’d found and the doctor there had tried, but Tillie had lost her baby a week later. It had taken another three weeks—since Tillie had almost died, too—before the doctor had declared she could travel again. The wagon train had long since left without them, so only the four women and their two wagons remained. That was also why she and Meg only had one dress each. They’d started the trip with two each, but had given the extra dresses and habits to Betty and Tillie. Four nuns traveling alone were safer than four single women. That was what Meg had said and they all believed she was right.

“Leaving you behind was never an option,” Lorna said. “And we are all better off being separated from the train. They were nothing more than army deserters and leeches. There wasn’t a man on that train I trusted, and very few women.”

“You got that right,” Meg said, joining her and Tillie on the ground.

“Furthermore,” Betty said, sticking her head out the back of the wagon, “taking you to see Dr. Wayne was our chance to escape.”

Lorna turned to Meg, and they read each other’s minds. Neither of them would have guessed that little Betty, heartbroken and quieter than a rabbit, had known of the dangers staying with the wagon train would have brought. Lorna and Meg had, and had been seeking an excuse to leave the group before Tillie had lost her husband and become ill.

Betty climbed out of the wagon and sat down with the rest of them. “I wasn’t able to sleep at night with the way Jacob Lerber leered at me during the day. Me! With Christopher barely cold in his grave.”

The contempt in Betty’s voice caused Lorna and Meg to share another knowing glance. Jacob Lerber had done more than leer. Both of them had stopped him from following Betty too closely on more than one occasion when she’d gone for water or firewood. Gratitude for the nun’s outfits had begun long before then. Everyone had been a bit wary of her and Meg, and kept their distance, afraid of being sent to hell and damnation on the spot. When Tillie had become ill, no one had protested against two nuns taking her to find a doctor. In fact, most of the others on the train had appeared happy at the prospect.

“But,” Tillie said softly, “because of me, we might not get to California before winter. It’s midsummer and we aren’t even to Wyoming yet.” Glancing toward Meg, Tillie added, “Are we?”

Meg shook her head. “But I’ve been thinking about that. There are plenty of towns along the way. I say wherever we are come October, we find a town and spend the winter. It would be good if we made it as far as Fort Hall, but there are other places. Having pooled our supplies, we have more than enough to see us through and come spring, we can head out again.”

Betty and Tillie readily agreed. Meg had become their wagon master, and they all trusted her judgment. None of them had anyone waiting at the other end, and whether they arrived this year or next made no difference.

To them. To Lorna it did. She needed to arrive in San Francisco as soon as possible. That was why she was on this trip, but she hadn’t told anyone else that. Not her reasons for going to California nor what she would do once she arrived and found Elliot Chadwick. That was the first thing she’d do. Right after getting rid of the nun’s habit. However, she also wanted to arrive in California alive. Others on their original train had told terrifying stories about being caught up in the mountains come winter, and claimed they couldn’t wait for Tillie to get the doctoring she’d needed.

Meg’s plan of wintering in a small town, although it made sense, wasn’t what Lorna wanted to hear. She didn’t want to pass the winter in any of the towns between here and California. The few they’d come across since leaving Missouri were not what she’d call towns. Then again, having lived in London most of her life, few cities in America were what she’d been used to, not even New York, despite having been born there.

“Lorna, you haven’t said anything,” Meg pointed out. “Do you agree?”

Meg might have become their wagon master, but for some unknown reason, they all acted as if Lorna was the leader of their small troupe. “Yes,” Lorna answered, figuring she’d hold her real opinion until there was something she could do about it. “Wherever we are come October, that’s where we stay.” She turned to Tillie. “And no more talk of being sorry. We are all here by choice.” Holding one hand out, palm down, she asked, “Right?”

One by one they slapped their hands atop hers. “Right!” Together they all said, “One for all and all for one.”

As their hands separated, Lorna reached for the diary that had tumbled off her lap. Too late she realized the others had read the brief entry she’d written for the day.

The women looked at one another and the silence thickened as Lorna closed the book.

Tillie picked up the pencil and while handing it back said, “How old will you be tomorrow?”

Lorna took the pencil and set it and the book on the ground. “Twenty.”

“I’m eighteen,” Betty said. “Had my birthday last March, right before we left Missouri.”

“Me, too,” Tillie said. “I’m eighteen. My birthday is in January.”

The others looked at Meg. She sighed and spit out a stem of grass she’d been chewing on. “Twenty. December.”

Betty turned to Lorna, her big eyes sparkling. “I have all the fixings. If we stop early enough tomorrow, I could bake a cake in my Dutch oven.”

Lorna shook her head. “No reason to waste supplies on a cake...or the time.”

Silence settled again, until Tillie asked, “Did you have cake back in England? Or birthday parties?”

Lorna considered not answering, but, ultimately, these were her friends, the only ones she had now. Meg didn’t, but Betty and Tillie, the way their eyes sparkled, acted as if living in England made her some kind of special person. No country did that.

“Yes,” she said. “My mother loved big, lavish parties, with all sorts of food and desserts, and fancy dresses.”

“What was your dress like last year?” Betty asked, folding her hands beneath her chin. Surrounded by the black nun’s habit, the excited glow of her face was prominent.

Lorna held in a sigh. She’d rather not remember that night, but couldn’t help but give the others a hint of the society they longed to hear about. “It was made of lovely dark blue velvet and took the seamstress a month to sew.”

“A month?”

She nodded. “My mother insisted it be covered with white lace, rows and rows of it.”

“You didn’t like the lace,” Meg said, as intuitive as ever.

Lorna shrugged. “I thought it was prettier without it.”

“I bet it was beautiful,” Betty said wistfully. “How many guests were there?”

“Over a hundred.”

Tillie gasped. “A hundred! Goodness.”

Lorna leaned back against the wagon wheel and took a moment to look at each woman. In the short time she’d known them, they had become better friends than anyone she’d known most of her life. Perhaps it was time for her to share a bit of her story. “It was also my engagement party. I was to marry Andrew Wainwright. The announcement was to be made that night.”

While the other two gasped, Meg asked, “What happened?”

“Andrew never arrived,” Lorna answered as bitterness coated her tongue. “Unbeknownst to me, he’d been sent to Scotland that morning.”

“Sent to Scotland? By whom?” Betty asked.

“His father,” Lorna said, trying to hold back the animosity. It was impossible, and before she could stop herself, she added, “And my stepfather.”

“Why?”

Night was settling in around them, and inside, Lorna was turning dark and cold. She hated that feeling. Her fingernails dug into her palm as she said, “Because my stepfather, Viscount Douglas Vermeer...” Simply saying his name made her wish she was already in California. “Didn’t want me marrying Andrew.” Or anyone else, apparently. Since he’d made certain later that night that it would never happen.