Полная версия

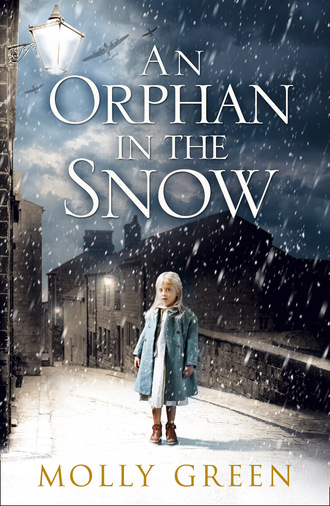

An Orphan in the Snow

With that list of chores for forty children she wondered how she’d fit in that hour for herself.

‘Any questions?’

‘Yes, Matron. I wasn’t told I’d have to help in the laundry or do the ironing. I thought that was Rose and Mabel’s job.’

‘Several of the orphans frequently wet the bed. It’s too much for the two girls without help.’

‘Couldn’t Hilda help out?’ June’s heart was beating nervously, hoping she wasn’t speaking out of turn.

Matron frowned. ‘She’s kept busy all the time. As I’ve told you before, we’re short-staffed as it is. There’s a war on, you know.’

‘Yes, I do know.’ June nearly added, ‘and my sister’s husband was killed in it,’ but managed to stop herself. ‘I’m not afraid of hard work, but—’

‘But nothing.’ Matron’s eyes flashed. ‘These orphans are obviously more of a challenge than your sister’s three boys. So if you don’t feel you’re up to the job, perhaps you should be looking elsewhere.’

‘No, of course I’ll do my very best.’ June folded the sheet of paper and put it in her overall pocket.

‘Then that’ll be all, Miss Lavender.’

‘I wondered where you’d got to,’ Iris said under her breath as June slipped into the common room.

‘I was worried about Lizzie and went up to the nursery but the door was locked so I couldn’t get in. Then Gilbert sneaked up behind me, making me jump, and asked what I was doing. He was quite rude.’

Iris’s face was serious. ‘Don’t take any notice of him. And no, I don’t approve at all of her being left alone, and neither does Kathleen. But you can’t tell Matron, and I’m afraid Hilda hasn’t got much between the ears.’

‘I’ve just had a bad run-in with Matron.’

‘Haven’t we all.’ Iris grinned. ‘What happened?’

June told her briefly what had taken place, and showed her the long list of duties.

‘She’s having a laugh,’ Iris said. ‘You’re a trained nursery nurse. You shouldn’t have anything to do with the laundry. You’re Matron’s assistant.’

‘But I have no idea what Matron does.’

‘As little as she can get away with,’ Iris said. ‘She disappears several times a day. We’ve all seen her sneak off to her cottage. Probably has a quick one. You can always smell it.’ She wrinkled her nose.

‘Do you mean a cigarette?’

‘That, too, I expect,’ Iris said. ‘But mainly a drink, and I don’t mean a bottle of lemonade either.’

June’s heart plummeted. Knowing how her mother had taken to drink after Clara died, June knew Matron was not going to be easy. But she wasn’t here to make such observations. Her duties lay with the children.

‘You said you’d tell me what happened to Lizzie.’

Iris looked from side to side out of the corner of her eyes. ‘Let’s go to my room and I’ll tell you what I know.’

Although Iris’s room was bigger than June’s it was so untidy it only looked half the size. Her nurse’s uniform was half dangling over a chair, the cap fallen to the floor, and to June’s embarrassment there was a brassière and a pair of knickers underneath. And a distinct smell of tobacco.

Iris laughed. ‘You’re obviously the neat type, Junie,’ she said. ‘I can’t keep anything in order in my own room but I’m completely the opposite when I’m working. Fussy as a housewife with her front doorstep, that’s me. And I never want to be one of those – housewives, I mean.’ She laughed again. ‘Here. Sit on the end of the bed. It’s more comfortable than the chair.’ She hauled a pile of papers and a pair of slippers off the only chair and dropped into it.

‘Don’t you want to get married one day?’ June ventured a little tentatively. She wasn’t used to asking personal questions of people she hardly knew, but Iris was different.

‘What? Tied down to some man who expects you to wait on him hand and foot. Then a load of snivelling kids to bring up single-handed because he’s gone all day.’ She glanced at June’s disbelieving face. ‘I’m put off having my own when I see my friends’ brats. No, thanks. Definitely not for me.’

‘But you’re here working with children.’

‘True. But these kids are different. They’re a challenge. They don’t have a normal home. This is all they know, poor little blighters. I don’t mind them.’

‘So tell me about Lizzie,’ June said, relieved that Iris was just as nice as she’d first thought.

‘It happened a couple of months ago. Lizzie was at her grandmother’s house for a few days and while she was away her house was hit in a bombing raid and caught fire. It was terrible.’ Iris’s voice began to quiver. ‘The fire engine got there too late. They all died. Her brother, who was only seven, and both parents.’

A shiver ran down June’s back making her gasp. She could feel tears pricking at the back of her eyes, imagining Lizzie, not even four, trying to understand where her mummy and daddy and brother had gone.

‘Since she came here the poor little kid hasn’t spoken a word.’ Iris searched in her bag for her packet of cigarettes, took one out and offered it to June, who shook her head. Iris put it between her own lips and flipped a silver lighter until it flared, then inhaled deeply before she let it out in a stream.

June felt the smoke catch the back of her throat and she tried not to cough.

‘What about the grandmother?’ she asked.

‘She used to come and see her once a week,’ Iris said. ‘But she’s getting old. Said she couldn’t bring up the child on her own. It was too much responsibility. And it was her son who died in the fire, and her grandson. She’s beside herself with grief. It was just too much for her. You can’t blame her.’

‘And Lizzie doesn’t even talk to her grandmother?’

‘Not a word. She stares at her as though she doesn’t even recognise her. It breaks Mrs Dixon’s heart. She hasn’t been to see her lately. I don’t think she can bear it, poor thing.’

‘Can we go and see Lizzie?’

‘I don’t see why not. C’mon, let’s go now while the kids are having their nap.’

The two girls ran up the flights of stairs and Iris took out a bunch of keys from her pocket, unlocked the door and pushed it open. Apprehensive of what she might see, June noticed Lizzie curled up in a corner like a frightened animal, clutching a ball of wool.

‘Hello, Lizzie, it’s Nurse Iris come to see you. I’ve brought Miss Lavender.’ Iris caught June’s arm and gently propelled her forward.

Lizzie curled up even smaller if that was possible, her eyes staring, her expression blank. She had three fingers in her mouth.

‘Take those fingers out, lovey, and say hello to Miss Lavender.’

‘Hello, Lizzie.’ June stepped a few inches closer. Lizzie tightened up, letting the wool fall on to the floor, her hands covering her eyes. ‘Lizzie, do you remember I came into the kitchen yesterday and said hello to you? Can you take your hands away so I can see your pretty face?’

The little girl moved her hands a fraction so June could just see part of her eyes.

‘Maybe tomorrow you’ll let me see you properly,’ June said.

‘Here – what’s going on?’

June turned at the harsh voice from the door. A girl of about 16, built like an ox, stormed in. Lizzie began to cry.

‘Hilda, this is Matron’s assistant, Miss Lavender,’ Iris explained. ‘I’m introducing her to Lizzie.’

‘You can see you’ve frightened her,’ Hilda squealed. ‘If you don’t leave this minute I’ll report you to Matron – both of you.’

Lizzie cried even louder.

‘You need to watch yourself, Hilda,’ Iris said, irritation with the girl colouring the words. ‘I may be putting in my own report – and it won’t be to Matron, either.’

‘She’s not the right person to be in charge of Lizzie,’ June said, when they were downstairs again. ‘Lizzie needs someone gentle and understanding and encouraging. I don’t think she’ll ever get that from Hilda.’

‘You’re right. She was only here a few weeks before Lizzie arrived so I don’t know her that well, but I’m not keen, I must say.’ Iris turned to look at June directly. ‘What do you think, June? Do you still think we should force Lizzie to play with the others? Have her meals with them?’

‘Maybe not right away, and I don’t think we should force her to do anything, but little by little I think we should include her in some games, and if all goes well, let her sit with us at mealtimes.’

‘I agree. She’s such a dear little poppet … must be lonely as hell. Pretty little thing too.’

‘It doesn’t really matter if she’s pretty or not,’ June said, her eye on Matron’s door. ‘She should be treated kindly and lovingly. She’s just lost both her parents and her brother. She hasn’t anything more to lose – except her voice,’ she added soberly. ‘That’s what’s so terrible. She can’t communicate with anyone.’

‘Any suggestions?’

‘Not yet, but I’m going to make it my mission to help her.’

Chapter Six

The next two days slipped by quickly as June tried to take everything in and work through Matron’s list. Daisy and Doris came out of the sick ward but they didn’t join in with the younger children’s favourite game of hide-and-seek or practise with the skipping rope, and June noticed they left half their food. She wondered how long they’d been at Dr Barnardo’s, and the reason why they’d come. She’d ask Matron. She’d also ask Matron if she could see a list of every child’s name and date of birth, and who their parents were, if known, and how the child had come to be at Dr Barnardo’s. It was important to know everything possible about each child and Matron was bound to keep a book with those sorts of details.

She decided to waylay Matron immediately after the children went to their first class of the morning.

‘Matron, it would help me a lot if I knew the different backgrounds of the children and I wondered if I could have a look at the records—’ She broke off when she saw Matron’s frown. ‘Just to acquaint myself,’ she added hurriedly.

‘I don’t see that’s necessary at all, Miss Lavender. They’re confidential.’

‘Yes, I understand, but surely not to the people who work with the children. It’s difficult to know how to handle them when I know nothing about them. They’re all individuals with different stories and I feel I’d be able to help them far more if I knew them better.’

‘You will know them better when you’ve been here longer, I’m sure.’ Matron’s voice and body were stiff with annoyance that she was being challenged.

‘No, they don’t say much about the reasons why they’re here. Not the orphans anyway. The evacuees sometimes tell me about their mums and dads. They have their own problems of homesickness, but the orphans are the ones who I believe need more attention. And sometimes the evacuees taunt the others. Only the other day I heard Arthur say to Jack, “I’ve got a mummy and daddy and you haven’t. I’ll go home soon and you’ve got to stay here forever.”’

‘Bates is always playing up.’ Matron pursed her lips. ‘He’s a troublemaker.’

‘Yes, he can be difficult.’ June sighed inwardly. She didn’t feel she was getting through to Matron at all. ‘But I don’t think he’s deliberately being horrible. I’m trying to show him his remarks are hurtful, but I have to tread carefully not to make him worse. If I knew more about him—’

‘Yes, yes, you’ve already told me,’ interrupted Matron pulling the chain of her watch out and looking at the time in a pointed manner. ‘Well, Miss Lavender, I’ve enjoyed our little chat, but I must get on. I believe you are down to darn their socks this afternoon, am I not correct?’

‘Yes, but—’

June’s words were lost as Matron turned on her heel and marched off, her shoes clacking on the wooden floor.

How was she going to find out about the children? A few of them had told her snatches, all of them sad stories, but several of them refused to discuss it. The boys were more secretive than the girls, and bit back their tears. She longed to take them in her arms and comfort them the way a mother would, but she daren’t. Matron had said only yesterday that displays of affection didn’t sit well at any Dr Barnardo’s home. Made the children weak, she’d said. They’d have to go out in the world as soon as they were old enough and needed to be independent. They’d thank her one day.

‘Are you coming to the dance, Junie?’ Iris asked, when the two girls were in the common room that evening after supper and the younger children were tucked up in bed. June had read them a story and was pleased to see they were all listening to her intently. When she asked who usually read them one, the answer took her by surprise.

‘No one, Miss.’

‘No one ever reads to you?’

‘No, Miss.’

‘Did you enjoy the story?’

‘Oh, yes. We’d like a story every night. Can we?’

‘Can we?’ Two children jumped up and down on their beds.

The others followed, all calling out, ‘Can we, can we?’

‘You’re not too old?’

‘No,’ they all chorused.

‘Well, all right, so long as you behave,’ June said, smiling. The children had settled down instantly. ‘And if I’m not ill or too busy, I’ll read you a story every night.’

‘Will you really, Miss?’ Peter’s eyes had shone with delight. ‘That’d be grand.’

Now Iris broke into her thoughts with talk of the dance.

‘I’m working,’ June told her, annoyed with herself for wondering not for the first time if Flight Lieutenant Andrews would be there, and trying to pretend her heart didn’t give a tiny leap each time. ‘And I don’t want to ask Matron any favours when I’ve only been here such a short time.’ June leaned towards the nurse. ‘Iris, can I ask you something?’

‘Sure.’

‘How long have you been at Dr Barnardo’s?’

‘Oh, dear, I thought you were going to ask me a really tricky question.’ Iris leaned back in her chair and laughed. ‘Let’s see. It must be coming up two years.’

‘Do you like it here?’

‘It’s as good as anywhere,’ Iris said. ‘Better if we had a nicer matron – a proper one who actually works. The Fierce One’s a harridan and lazy with it. That’s why she’s got you here. She can push all the jobs she doesn’t like on to you. She’s been here forever and thinks she owns the place. And she’s got no kids of her own – not that I have’ – Iris threw June a grin – ‘but she doesn’t have the first clue that the kids need affection and individual attention, and it’s just as important as their food and a roof.’ She pulled a packet of cigarettes from her handbag and plucked one out. ‘You’re changing the subject, Junie, and I’m not taking no for an answer. I’m going to have some fun. And you’re coming with me.’

‘Message from Matron,’ Kathleen said, flopping down in the chair next to June. ‘She wants to see you in her office – NOW!’ she barked in Matron’s strident voice. Barbara, who was crocheting a bedspread, chortled.

June’s heart dropped. Iris had warned her that Matron didn’t usually call you into her office unless it was something serious. Her usual habit was to waylay you in front of as many people as possible to criticise you – her way of feeling superior, she supposed. But if she wanted to give you a real dressing-down, that’s when she sent for you.

June went straight to Matron’s office and knocked.

‘Enter.’

June turned the handle and opened the door to Matron’s office. The room was so full of smoke she could hardly make out the figure sitting behind the desk. Matron had an accounts book open and was reading the figures, but June had the distinct feeling the woman didn’t understand them from the way she was flicking the pages back and forth. June cleared her throat in a pointed way. Matron looked up.

‘Oh, there you are, Miss Lavender. You can be seated.’

June sat with her hands quietly folded in her lap, determined not to be intimidated by the woman. She drew in a deep breath, wondering what was coming.

‘Hilda Jackson has put in a complaint about you which I take very seriously indeed.’

Lizzie.

‘You interfered with one of her special charges, Lizzie Rae Dixon.’

June opened her mouth.

‘No, Miss Lavender. I would prefer not to hear any excuses. Hilda has explained exactly what happened. The child needs special attention and Hilda has been assigned to give it to her. She did not take kindly to your interference and I will not tolerate such behaviour. You are not to go up to the nursery again, do you hear me?’

‘Matron, I didn’t interfere, as you call it. I just—’

‘Silence!’ Matron slapped her hand hard on her desk. ‘I will also not tolerate such rudeness. I shall be keeping a close eye on you, so watch your step in future, Miss.’ She snapped the accounts book closed. ‘You are dismissed.’

June bit her lip in fury to stop herself making a retort. How dare Matron speak to her as though she were a naughty child. If she’d only let her tell her side of the story. How Hilda did the complete opposite of giving the little girl attention and love which the child was crying out for. Leaving her completely on her own while she went down to the dining room and ate her own dinner, and then bringing a plate back for Lizzie. The child could get up to anything in those twenty minutes. No, Hilda was not the right person to be put in charge of her. But how on earth was she ever going to convince Matron? But whatever Matron threatened, June was determined she was going to try to talk to Lizzie again. To break through that wall of silence.

The only place Lizzie would go outside the nursery was into the kitchen with Cook. That was the best place to talk to her, June thought, because at least Bertie had shown the child kindness. But she couldn’t risk Matron’s temper if she went to see Lizzie in work time. No, she’d leave it until her next day off. Then she could do what she liked. Go into the kitchen and have a cup of tea with Bertie if the cook wasn’t too busy and maybe Lizzie would be there. Even so, it wouldn’t be easy. The child was suspicious of everyone, it seemed, with the possible exception of Cook.

June fell into bed, exhausted by the children. It was as though they sapped all feeling, all strength, until her head spun. But at least she now knew their names. The worst of it was she already had favourites. She’d been determined not to. It wasn’t fair on the others. But who could resist little Betsy with her skin the colour of treacle and her dark-brown eyes which she used in a comic fashion when she wanted to make you laugh? June couldn’t help smiling at the vision. And Harvey with his mocking grin and legs that showed recent scars, which could only have come from someone beating him. He bragged he could play any tune you asked for on the mouth organ, and so far he’d never wavered. Then there was quiet little Janet, a shy plump child with an extraordinary vocabulary for an eight-year-old. She’d sit for hours making tiny books and writing and drawing in them.

The children took her mind off painful memories. But June always came back to Lizzie.

Once or twice June had been tempted to remind Iris about the dance, but decided her friend would immediately tease her that she was looking for a man. She momentarily closed her eyes. A certain face whose image refused to go away. A strong face with the bluest eyes that crinkled when he laughed. The cleft in his chin like Cary Grant’s. The shiny hair, the colour of a tawny lion. You see, it’s happening right this minute, she berated herself, trying to push his image away. She was being ridiculous. Their encounters would have meant nothing more to him than a brief exchange of pleasantries. Actually, that first time on the train was more of a battle. She couldn’t help smiling at the memory, and Iris, who was collecting the dirty supper dishes, caught the smile and grinned back.

‘Penny for them.’

June went pink.

‘Ah, I thought so,’ Iris said, nodding sagely. ‘It’s the RAF chap. Well, the only way you’re going to see him again is if we go to the dance on Saturday. The girls in the kitchen aren’t going as it’s an officers’ do and they don’t feel comfortable with them, even though they admit they look gorgeous in their uniform. But they prefer the soldiers.’ She gave June a sharp look. ‘What’s the matter? You’re very quiet all of a sudden.’

‘I’m not sure I’ll feel comfortable with a load of posh officers.’

‘Posh?’ Iris threw back her head and roared. ‘You should hear some of them. Granted, they might talk hoity-toity but believe me, we’re just as good as them any day of the week.’

‘All right, you’ve convinced me,’ June said, grinning. ‘And maybe one of these days I’ll surprise you and take you up on that offer of a cigarette. I’ve never tried one but everyone else seems to enjoy it. Maybe it’s time I did something different.’

She didn’t know what made her say this. Smoking was something that had never appealed, but in her new job at Bingham Hall she badly wanted to fit in.

Her eyes gleaming with mischief, Iris gave June a sly nudge. ‘That’s my girl. We’ll give it a go this evening. I’ll get Gilbert to light the fire early in the common room so we’ll be nice and cosy and can have a girls’ natter. There shouldn’t be anyone in there tonight as they’ve nearly all signed up for Barbara’s new evening art class.’

June changed her mind a dozen times as to whether she should go with Iris to the dance or not. She really didn’t have anything to wear such as a party dress, as she hadn’t envisaged needing one. And even if she had, she didn’t have the coupons or the money to buy something that wasn’t practical – something she’d hardly ever wear.

‘You’re coming, and that’s all there is to it,’ Iris said as they sat in the common room drinking a cup of tea.

They were on their own except for Athena, who had her head in a book and didn’t seem to be taking any notice of their conversation.

‘What will you wear?’ June posed the question to Iris, half dreading her friend would come up with something really glamorous.

‘I’m going to wear my navy spotted dress with white collar and cuffs. I bought it before the war so it’s not new, if that’s what you’re thinking.’ She turned her sapphire-coloured eyes to June. ‘You don’t need to worry about wearing sequins for the dance. The chaps are just grateful to see any woman, whether she’s in uniform or just come off the land smelling of manure with corn sticking out of her hair and a bag of turnips in her arms.’

June couldn’t help laughing. ‘Gosh, they must be desperate.’

‘I think some of them are.’ Iris’s expression was suddenly serious. ‘These boys really see life – and it’s often extremely unpleasant with your friends getting injured and blown up at any time. So a dance means more to them than we’ll ever know. They always seem optimistic that they just might meet the girl of their dreams. Even if it’s only someone who’ll write to them when they’re abroad to stop them going mad. Can you imagine their lives – flying around trying to shoot down Germans and desperately trying not to get killed themselves?’

‘I can’t.’ June felt sick at the idea. Murray’s face flitted across her mind. She’d been curt with him when he hadn’t deserved it and it made her feel thoroughly mean. He’d only been trying to be nice and she’d cut him off – more than once. Was it because she liked him and didn’t want to let herself become interested in anyone who might be killed at any moment? A shudder ran across her shoulders.

‘… and I don’t suppose your Murray is any different.’

June gave a start as she heard Iris say his name.

‘Junie, have you heard a word I’ve been saying?’

‘I’m sorry, Iris. I was miles away.’

‘Thinking of Murray Andrews, were we?’ Iris’s eyes twinkled mischievously. ‘I daresay he’ll be at the dance.’

June’s heart skipped the next beat.

‘’Course I wasn’t,’ she answered crossly. ‘I was thinking of what you said about all of them. It must be awful.’

‘Well, they’ll soon have a load of Yanks to see to,’ Iris said. ‘It will give them something to grumble about. I’ve heard their uniforms are much more attractive than our boys’, and they’ve got more money too. And they’re very generous with their gifts, so I’m told – nylons and chocolate and all sorts of luxuries we can’t get.’