полная версия

полная версияHandbook to the new Gold-fields

The following personal testimony may also be cited:– “On Sunday,” says the San Francisco Globe, “we received a visit from Messrs Edward Campbell and Joseph Blanch, both boatmen, well known in this city, who have just returned from the mines on Fraser River. They mined for ten days on the bar, until compelled to desist from the rise in the river, in which time they took out 1340 dollars. They used but one rocker, and have no doubt that they could have done much better with proper appliances. There were from sixty to seventy white men at work on Hill’s Bar, and from four to five hundred Indians, men, women, and children. The Indians are divided in opinion with regard to Americans; the more numerous party, headed by Pollock, a chief, are disposed to receive them favourably, because they obtain more money, for their labour from the ‘Bostons’ than from ‘King George’s men’, as they style the English. They have learned the full value of their labour, and, instead of one dollar a-day, or an old shirt, for guiding and helping to work a boat up the river, they now charge from five to eight dollars per day. Another portion of the Indians are in favour of driving off the ‘Bostons,’ being fearful of having their country overrun by them.”

The proprietor of the San Francisco News Letter had determined to be at the centre of the present excitement in the El Dorado, and to judge for himself, or, rather to solve the problem of how much gold, how many Indians, and how much humbug, went on board the Pacific mail steam-ship Cortes, Captain Horner, and made the passage to Victoria, 840 miles, in five days. Although nine hundred persons were on board, yet no actual inconvenience was felt by the high-pressure packing; the greatest good humour and accommodating spirit prevailing, controlled by the gentlemanly conduct of Captain J.B. Horner and his officers. On the day of arrival, the operations of the Government Land Office at the fort in Victoria was 26,000 dollars. The importance of the amount can best be realised by comparing it with the prices, viz. 100 dollars per lot, 60 by 100 feet, unsurveyed. Some of these lots have been sold at 200 to 1000 dollars. Lots at first sale, surveyed price, 50 dollars; lots, second and last sale, 100 dollars each, are now being sold from 500 to 1000 dollars each. Six lots together in the principal street are valued at 10,000 dollars. The figures at Esquimault Harbour and lots in that vicinity assume a bolder character as to value, from the fact that the harbour is a granite-bound basin, similar to Victoria, with an entrance now wide and deep enough to admit the Leviathan. Victoria has a bar which must be dredged, dug, or blown away. We noted at Victoria that the most valuable lot, with a flat granite level, with thirty feet of water, sufficient for any ship to unload without jetty, is now covered by a large building constructed of logs, belonging to Samuel Price and Company. A ship was unloading lumber at this wharf at 35 dollars per M, which was the ruling price. At Victoria, on the 21st June, a Frenchman landed from the steamer Surprise, who came on board at Fort Langley with twenty-seven pounds weight of gold on his person, which we saw and lifted. Another passenger, whom we know, states that there are six hundred persons within eight miles of Fort Hope, who are averaging per man an ounce and a half of gold per day minimum to six and a half ounces per day maximum. The largest sums seem to be taken out at Sailor’s Bar, five miles above Fort Hope. The lowest depth as yet reached by miners is fifteen inches; these mere surface scratches producing often 200 dollars per day. At Fort Hope, potatoes were selling at 6 dollars per bag; bacon, 75 cents per pound; crackers, 30 cents. From Fort Hope to Fort Thompson the road is good, with the exception of twenty miles. For 20 dollars, the steamers will take miners from Victoria to the diggings at Fort Hope, and for three or four dollars more an Indian will accompany you to Fort Yale. Bowen, steward of the Surprise, says that about a hundred Indians usually ran after him to obtain little sweet cakes, which he traded off four or five for 1 dollar in gold dust. Sugar at Fort Langley, 1 dollar 50 cents per pound; lumber, 1 dollar 50 cents per foot; tea and coffee, 1 dollar per pound; pierced iron for rockers, 8 dollars; plain sheets, 2 dollars each; five pounds of quicksilver sold for 40 dollars—10 dollars per pound was the ordinary price. The actual ground prospected and ascertained to be highly auriferous extends to three hundred and fifty miles from the mouth of Fraser River. One hundred miles of Thompson River has been prospected, and found to be rich, south-east of Fraser River. The same will apply to all the tributaries of Thompson River. A large extent of auriferous quartz has been discovered ten miles from Fort Hope. Exceedingly rich quartz veins have been found on Harrison River.

The most astounding facts have yet to be divulged. A river emptying into the Gulf of Georgia, not a hundred miles north of Fraser River hitherto supposed to contain no gold, has proved fabulously rich. An Indian arrived at Victoria from this locality, having twenty-three pounds weight of pure gold, obtained solely by his own labour, in less than twenty days. In confirmation of our figures, and being short of space, we append the following statistics, derived from an official and authentic source of the strictest reliability. We deem the above facts sufficient to cause an exodus of a far more alarming character, and of higher proportions as to number, than any hitherto known in history. Suffice it to say, that the present furore is well founded; that it holds out busy times, high prices, speculations, contracts, and employments of a thousand kinds.

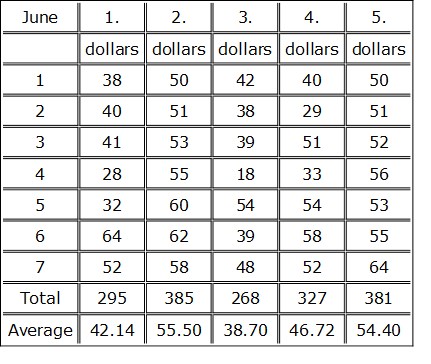

Fountain’s Diggings (Fraser River, at 51 degrees 30 minutes north), month of June 1858.

Five rockers worked by half-breed Canadians.

A highly reliable correspondent sends the following from San Francisco, under date 5th July:—

The emigration for Fraser River has gone on for months with no signs of growing less. The best means of judging what grounds there are for the belief in the existence of gold in large quantities on its banks, is by letters received from persons who are engaged in mining. It is worthy of note that there is no discrepancy between the accounts given by different individuals, all their statements agreeing. The mines are reported to be exceedingly rich, and yielding large returns to those engaged in digging. The river is very high, and miners have been driven from several of the most lucrative bars until the water subsides. Mr Hill, from whom Hill’s Bar took its name, is mining some distance above that point. He and six hands were making from an ounce to an ounce and a-half of gold dust a day to each man. For three weeks prior to the freshet, Mr Hill and one man averaged one hundred to one hundred and fifty dollars a day. The freshet, however drove him off for the time being. Mr E.R. Collins, who has spent some time in the Fraser River gold region, and who brought down last week a quantity of dust, has communicated the following intelligence to the Alta California. Mr Collins is a trustworthy gentleman. He left San Francisco in March last, and was at Olympia when the excitement first broke out. He then, in company with three others, proceeded to Point Roberts, from whence they proceeded up Fraser River to the mouth of Harrison River, about twenty-five miles above Fort Langley. This portion of the journey they performed without guides or assistance from the natives. The current was moderate, and occasionally beautiful islands were discovered with heavy timber, which presented a beautiful appearance. From Fort Hope to Fort Yale, a distance of fifteen miles, the river runs narrow, and the current running about seven miles per hour, though, in some places, it might be set down at ten or twelve. At Fort Yale, the first mining bar was reached. It extended out from the left bank a distance of some thirty yards, and was about half a mile long. Twenty or thirty squaws were at work with baskets and wooden trays, while, near by, large numbers of male Indians stood listlessly looking on. Here some of Mr Collins’ companions, who had now increased to twenty, proposed to stop and try their luck, but the majority resolved to go on, having informed themselves satisfactorily that further up the “big chunks” were in abundance. After resting a while, therefore, the party went ahead. Two miles from Fort Yale they entered upon the commencement of the real difficulties and dangers of navigation on Fraser River, the water for a distance of thirty-five or forty miles passing through deep gloomy cañons, and over high masses of rock. At this time the river had attained only a few feet above its usual height, so that by perseverance and the skill of the native boatman they were enabled to make slow progress. Numerous portages were made—one of them, the last, being four miles long. These portages could not be avoided, the cliffs rising perpendicularly on either side of the river, sometimes to a height of fifty or sixty feet, affording not the slightest footpath on which to tow. At other places the whirls, and rocks partly submerged, rendered a water passage utterly impracticable. At every bar and shallow spot prospected in these wild localities gold was obtained in paying quantities, all of very fine quality—rather difficult to save without the use of quicksilver. From the head of the cañons to the forks of Thompson’s River, thirty-five miles more, the current and general appearance of the river seemed about the same as from Fort Hope to Fort Yale, gold also being found where there was an opportunity for a fair “prospect”. At the Forks the party were told by Travill, a French trader, whom they met by accident, that the richest and best diggings were up Thompson’s; but that river being navigable but a few miles up, it was thought best to keep on up Fraser, which they did for a distance of forty miles, encountering no serious obstacles beyond a few rapids, and they were passed by towing. Five miles above the Forks some twenty white men were at work, making with common rockers from ten to sixteen dollars per day. Arriving at a bar about ten miles below, where white men were congregating in numbers considered sufficient for mutual protection, they took up a claim and commenced digging. They worked here steady twenty-four days, averaging fifteen dollars per day to each man. The greatest day’s work of one man was thirty-one dollars. These figures, it is thought, would apply to all the miners.

Our latest news from the new mines reach to the beginning of July. At that time there were immense numbers of miners on the banks of Fraser River, waiting for the stream to fall and enable them to go to work on the bars, which are said to be fabulously rich. Some dry diggings had also been discovered in the neighbourhood of the river; but owing to the presence of a large number of Indians, not of the most friendly disposition, the miners dared not then extend their researches far from the stream, where the bulk of the whites were congregated. The town of Victoria, on Vancouver’s Island, has sprung rapidly into importance. Great advances have been made on real estate there. Lots, which a few months ago were sold by the Hudson’s Bay Company at twelve pounds ten shillings, are now selling at over 250 pounds. A newspaper, called the Victoria Gazette has been started there; and an American steamer, The Surprise, is also running regularly between Victoria and Fort Hope, which is one hundred miles above the mouth of Fraser River. In the last week of June the arrivals by steamers and vessels at the various ports of British Columbia reached the large daily average of one thousand, while those who have lately travelled through the mountains say that the principal roads in the interior present an appearance similar to the retreat of a routed army. Stages, express waggons, and vehicles of every character, are called into requisition for the immediate emergency, and all are crammed, while whole battalions are pressing forward on horse or mule back, and on foot. Of course, the shipments of merchandise from San Francisco and other ports are very large, to keep pace with this almost instantaneous emigration of thousands to a region totally unsupplied with the commodities necessary for their use and sustenance. Up to the present no outbreak or disturbance has occurred, and a certain degree of order has already been established in the mining region, through the judicious measures adopted by the governor. Justices of the peace and other officials have been appointed, and a system protective of the territorial interests organised. Licences, on the principle of those granted in Australia, are issued; the price, five dollars per month, to be exacted from every miner. There was a good deal of talk, as to the right or propriety of levying this tax when it was first proposed, and some of the Francisco papers were load in their denunciations; others took a calmer view. It is satisfactory to add that little difficulty has so far been experienced on this head. As a body, the miners are reported to be a steady set of men, well conducted, and respectful of the law.

Chapter Two

Climate, Productions, and Soil

Next to the extent and richness of the gold mines, the most important inquiry is as to the character of the climate and soil. And in this respect the Fraser River settlement does not lose any of its attractions, for, though seven hundred miles north of San Francisco, it is still one or two degrees south of the latitude of London, and apparently with a climate of a mildness equal to that of the southern shores of England, being free from all extremes, both of heat and cold. One hundred and fifty miles back from the Pacific, indeed, there lies a range of mountains reaching up to the regions of perpetual snow. But between that and the coast the average temperature is fifty-four degrees for the year round. Snow seldom lies more than three days. Fruit trees blossom early in April, and salad goes to head by the middle of May on Vancouver’s Island. In parts of this region wheat yields twenty to thirty bushels to the acre. Apples, pears, pease, and grains of all kinds do well. The trees are of gigantic growth. Iron and copper abound, as does also coal in Vancouver’s Island, so that altogether it bids fair to realise in a short time the description applied to it by the colonial secretary (Sir E.B. Lytton), of “a magnificent abode for the human race.”

When introducing the “Government of New Caledonia bill,” on 9th July, the Colonial Secretary said in his place in the House of Commons:– “The Thompson River district is described as one of the finest countries in the British dominions, with a climate far superior to that of countries in the same latitude on the other side of the mountains. Mr Cooper, who gave valuable evidence before our committee on this district, with which he is thoroughly acquainted, recently addressed to me a letter, in which he states that ‘its fisheries are most valuable, its timber the finest in the world for marine purposes; it abounds with bituminous coal, well fitted for the generation of steam; from Thompson River and Colville districts to the Rocky Mountains, and from the 49th parallel some 350 miles north, a more beautiful country does not exist. It is in every way suitable for colonisation.’ Therefore, apart from the gold fields, this country affords every promise of a flourishing and important colony.”

The Times special correspondent, in a letter from Vancouver’s Island, published on 10th August, says, “Productive fisheries, prolific whaling waters, extensive coalfields, a country well timbered in some parts, susceptible of every agricultural improvement in ethers, with rich gold fields on the very borders—these are some of the many advantages enjoyed by the colony of Vancouver’s Island and its fortunate possessors. When I add that the island boasts a climate of great salubrity, with a winter temperature resembling that of England, and a summer little inferior to that of Paris, I need say no more, lest my picture be suspected of sharing too deeply of couleur de rose.”

Of the southern part of this district Lieutenant Wilkes, who commanded the late exploring expedition under the United States government, says, “Few portions of the globe are so rich in soil, so diversified in surface, or so capable of being rendered the happy homes of an industrious and civilised community. For beauty of scenery and salubrity of climate it cannot be surpassed. It is peculiarly adapted for an agricultural and pastoral people, and no portion of the world beyond the tropics can be found that will yield so readily with moderate labour to the wants of man.”

Perhaps the fullest account of the country yet given is that contained in “The Narrative of a Residence of Six Years on the Western Slopes of the Rocky Mountains,” by Ross Cox, one of the earliest explorers of British North America. He says, “The district of New Caledonia extends from 51 degrees 30 minutes north latitude to about 56 degrees. Its extreme western boundary is 124 degrees 10 minutes. Its principal trading post is called Alexandria, after the celebrated traveller Sir Alexander Mackenzie. It is built on the banks of Fraser River, in about latitude 53 degrees north. The country in its immediate vicinity presents a beautiful and picturesque appearance. The banks of the river are rather low; but a little distance inland some rising grounds are visible, partially diversified by groves of fir and poplar. This country is full of small lakes, rivers, and marshes. It extends about ten days’ march in a north and north-east direction. To the south and south-east the Atnah, or Chin Indian country, extends about one hundred miles; on the east there is a chain of lakes, and the mountains bordering Thompson River; while to the westward and north-west lie the lands of the Naskotins and Clinches. The lakes are numerous, and some of them tolerably large: one, two, and even three days are at times required to cross some of them. They abound in a plentiful variety of fish, such as trout, sucker, etcetera; and the natives assert that white fish is sometimes taken. These lakes are generally fed by mountain streams, and many of them spread out, and are lost in the surrounding marshes. On the banks of the river, and in the interior, the trees consist of poplar, cypress, alder, cedar, birch, and different species of fir, spruce, and willow. There is not the same variety of wild fruit as on the Columbia; and this year (1827) the berries generally failed. Service berries, choke-cherries, gooseberries, strawberries, and red whortleberries are gathered; but among the Indians the service-berry is the great favourite. There are various kinds of roots, which the natives preserve and dry for periods of scarcity. There is only one kind which we can eat. It is called Tza-chin, has a bitter taste, but when eaten with salmon imparts an agreeable zest, and effectually destroys the disagreeable smell of that fish when smoke-dried. Saint John’s wort is very common, and has been successfully applied as a fomentation in topical inflammations. A kind of weed, which the natives convert into a species of flax, is in general demand. An evergreen, similar to that we found at the mouth of the Columbia, with small berries growing in clusters like grapes, also flourishes in this district. Sarsaparilla and bear-root are found in abundance. White earth abounds in the vicinity of the fort; and one description of it, mixed with oil and lime, might be converted into excellent soap. Coal in considerable quantities has been discovered; and in many places we observed a species of red earth, much resembling lava, and which appeared to be of volcanic origin. We also found in different parts of New Caledonia quartz, rock crystal, cobalt, talc, iron, marcasites of a gold colour, granite, fuller’s earth, some beautiful specimens of black, marble, and limestone in small quantities, which appeared to have been forced down the beds of the rivers from the mountains. The jumping-deer, or chevreuil, together with the rein and red-deer, frequent the vicinity of the mountains in considerable numbers, and in the summer season they oftentimes descend to the banks of the rivers and the adjacent flat country. The marmot and wood-rat also abound: the flesh of the former is exquisite, and capital robes are made out of its skin; but the latter is a very destructive animal. Their dogs are of diminutive size, and strongly resemble those of the Esquimaux, with the curled up tail, small ears, and pointed nose. We purchased numbers of them for the kettle, their flesh constituting the chief article of food in our holiday feasts for Christmas and New Year. The fur-bearing animals consist of beavers; bears, black, brown, and grizzly; otters, fishers, lynxes, martins; foxes, red, cross, and silver; minks, musquash, wolverines, and ermines. Rabbits also are so numerous that the natives manage to subsist on them during the periods that salmon is scarce. Under the head of ornithology we have the bustard, or Canadian outarde (wild goose), swans, ducks of various descriptions, hawks, plovers, cranes, white-headed eagles, magpies, crows, vultures, wood-thrush, red-breasted thrush or robin, woodpeckers, gulls, pelicans, hawks, partridges, pheasants, and snow-birds. The spring commences in April, when the wild flowers begin to bud, and from thence to the latter end of May the weather is delightful. In June it rains incessantly, with strong southerly and easterly winds. During the months of July and August the heat is intolerable; and in September the fogs are so dense that it is quite impossible to distinguish the opposite side of the river any morning before ten o’clock. Colds and rheumatisms are prevalent among the natives during this period: nor are our people exempt from them. In October the falling of the leaves and occasional frost announce the beginning of winter. The lakes and parts of the rivers are frozen in November. The snow seldoms exceeds twenty-four inches in depth. The mercury in Fahrenheit’s thermometer falls in January to 15 degrees below zero; but this does not continue many days. In general, I may say, the climate is neither unhealthy nor unpleasant; and if the natives used common prudence, they would undoubtedly live to an advanced age. The salmon fishery commences about the middle of July, and ceases in October. This is a busy period for the natives; for upon their industry in saving a sufficiency of salmon for the winter depends their chief support. Jub, suckers, trout, and white-fish, are caught in the lakes; and in the month of October, towards the close of the salmon-fishery, we catch trout of a most exquisite flavour. Large-sized sturgeon are occasionally taken in the vorveaux, but they are not relished by the natives.”

Mr Dunn, in his valuable “History of the Oregon Territory,” thus describes the country and climate:– “After the Columbia, the river next in importance is Fraser River. It takes its rise in the Rocky Mountains, near the source of Canoe River, taking a north-west course of eighty miles. It then turns to the southward, receiving Stuart’s River, which rises in a chain of lakes in the northern boundary of the territory. It then pursues a southerly course, and after receiving many tributaries, breaks through the cascade range of hills in a series of falls and rapids; and after a westerly course of seventy miles, empties itself into the Gulf of Georgia, in latitude 49 degrees 7 minutes north. This latter portion is navigable for vessels that can pass its bar drawing ten feet of water. Its whole length is 350 miles. There are numerous lakes scattered through the several sections. The country is all well watered; and there are but four places where an abundance of water cannot be obtained, either from lakes, rivers, or springs.

“The climate of the western division is mild throughout the year, neither the cold of winter, nor the heat of summer predominating. The mean temperature is about 50 degrees Fahrenheit. The prevailing winds, in summer, are from the northward and westward, and in winter, from the west, south, and south-east. The winter lasts from about November till March, generally speaking. During that time there are frequent falls of rain, but not heavy. Snow seldoms lies longer than a week on the ground. There are frosts so early as September, but they are not severe, and do not continue long. The easterly winds are the coldest, as they come from across the mountains, but they are not frequent. Fruit trees blossom early in April in the neighbourhood of Nasqually and Vancouver; and in the middle of May pease are a foot high, and strawberries in full blossom; indeed, all fruits and vegetables are as early there as in England. The hills, though of great declivity, have a sward to their tops. Lieutenant Wilkes says, that out of 106 days, 67 were fair, 19 cloudy, and 11 rainy. The middle section is subject to droughts. During summer the atmosphere is drier and warmer, and in winter colder than in the western section; its extremes of heat and cold being greater and more frequent. However, the air is fine and healthy; the atmosphere in summer being cooled by the breezes that blow from the Pacific.