Полная версия

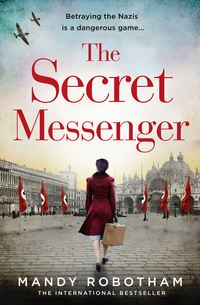

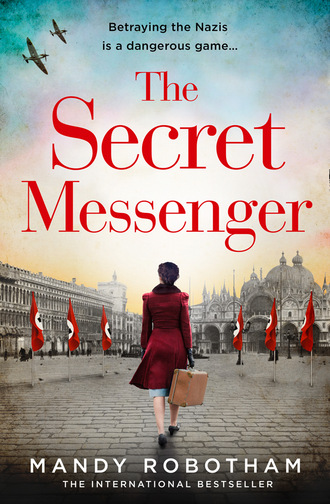

The Secret Messenger

THE SECRET MESSENGER

Mandy Robotham

Copyright

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Mandy Robotham 2019

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover photographs © Mary Evans Picture Library (Piazza San Marco, Venice), Elizabeth Ainsley/Trevillion images (woman), Shutterstock.com (flags, planes, sky)

Mandy Robotham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008324261

Ebook Edition © December 2019 ISBN: 9780008324254

Version: 2020-02-20

Dedication

To my mum, Stella – a woman of stamina and enduring style

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s note

Prologue: Clowns

Chapter 1: Grief

Chapter 2: The Lion’s Den

Chapter 3: Bedding In

Chapter 4: Discovery

Chapter 5: A New Task

Chapter 6: Two Sides of the Coin

Chapter 7: New Interest

Chapter 8: Finding and Frustration

Chapter 9: Drinks with the Enemy

Chapter 10: A New Role

Chapter 11: Casting Out

Chapter 12: Opening Up

Chapter 13: Story Time

Chapter 14: A Voice from the Lagoon

Chapter 15: Love and Fury

Chapter 16: A Lull

Chapter 17: On Hold

Chapter 18: Small Talk

Chapter 19: A Detour

Chapter 20: Arrival

Chapter 21: The City Cauldron

Chapter 22: The Seeker

Chapter 23: A Fiery Reaction

Chapter 24: Across the Lagoon

Chapter 25: A New Hope

Chapter 26: Revenge

Chapter 27: The Bloody Summer

Chapter 28: Seeking and Waiting

Chapter 29: Sorrow

Chapter 30: A Low Ebb of the Tide

Chapter 31: Playing Detective

Chapter 32: A Parting

Chapter 33: In Hiding

Chapter 34: The Search for Coffee

Chapter 35: Red-Handed

Chapter 36: Taking Flight

Chapter 37: Age and Enlightenment

Chapter 38: After

Chapter 39: Completion

Chapter 40: The Typewriter

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Author’s note

War is ugly. Wherever it strikes, it destroys people, families and places, decimates lives and precious objects. Yet being so widespread, conflict also happens in beautiful places, and it was that contrast of light and dark which prompted The Secret Messenger. For me, there is no more stunning or fantastical place on earth than Venice; since my first trip in 1990, I’ve been beguiled on countless visits by the idea of a city effectively floating. I’m still in awe of its very existence and its beauty.

When I began to research how World War Two affected Venice, it became clear that historians were less captivated by its story of Resistance as perhaps in France or the Netherlands; that Venice, by comparison, had experienced a ‘soft’ war. What research I found seemed brief and factual, but those details of Venetian life – of how Venetians existed day by day – were scant. On a research trip (yes, of course, I needed to go back again!) I walked miles through Venetian calles, itching to know which areas of the city played their part in the fight against the Nazis and fascists combined.

It wasn’t until my return home that I struck gold; a chance email launched into cyberspace sparked a reply from the wonderfully named Signor Giulio Bobbo, a historian at IVESER, the Venetian Institute for the History of Resistance and Contemporary Society. His own area of expertise? The Resistance in wartime Venice. It was like manna from heaven.

Thanks to Giulio, his grounding in factual research and the nuggets of priceless detail about real life in wartime Venice, the book began to take shape. At last, I could see a Venice under the cloak of war. The more Giulio and I traded emails, the more my search seemed to run parallel to the quest within the story – it seemed only fitting Giulio’s character should make an appearance, along with Melodie the cat who, by the way, is very real and does indeed love a warm photocopier!

I knew also that I wanted to highlight the role of women in the eventual victory over the Nazis; not only the bravery of undercover agents, but the army of female messengers across Italy – Staffettas – who helped the Allies to victory. It’s hard for us in this day of social media and instant messaging to understand the value of transporting a simple slip of information on foot or by boat, but in those times it was crucial. Life-saving, in fact. Without the thousands of mothers and grandmothers across Europe who risked their own lives by carrying contraband in prams and shopping bags, we might never have seen peace at all. I hope Stella is an embodiment of those women – selfless for those around them.

Once Stella and her city became my backdrop, the next element was easy. Where else is better suited for romance to blossom than a place that hovers amid the constant ripple of water and sits under the most stunning of sunsets? And, of course, my Venice is in there too: the Accademia is my favourite bridge, Campo Santo Stefano among my preferred piazzas to people watch, and there is a small café in the corner opposite the church doorway where I have sat many a time with a good coffee and my notebook, imagining myself as a writer. Oh, and to the side is a very good gelato parlour. You can’t escape it – Venice gets under your skin.

I hope I have paid homage to those who braved the conflict in Venice; there is no such thing as a ‘soft’ war when one person loses a life, one mother a son. Venice lost too. But as with the previous centuries of invasion and plague, it recovered. It remains a jewel. Glittering. And I’ll be back there soon.

Prologue: Clowns

Venice, June 1934

A sudden eruption of noise guided us – one burst after another, pushing up into the air like fireworks on a dark night. We zigzagged through the crowds, my grandfather slicing through the swarm with his broad muscular shoulders – still with a boat-builder’s strength despite his sixty-five years. Reaching the edge of the vast piazza he pulled me by the hand, threading his way to the front of the audience, which was fenced off with a line of black-shirted militia, their backs to the expanse of the square and their stern, fixed faces towards the crowd. Inside the square, lines of Italian troops paraded up and down like ants to a continual brass band pomp of military music.

At seventeen, I was of average height and had to crane my neck to see the object of our attention, along with the rest of the crowd. The imposing, rounded girth of Benito Mussolini was easily spotted – a common figure on the front pages of the fascist-run newspapers. Even from behind, he had the appearance of being smug and overbearing, strutting next to the slightly smaller man walking beside him, distinctive only because of his dark suit rather than a gilded uniform dripping with medals. There was nothing physically remarkable about Mussolini’s revered guest from the distance we were at. I knew who he was, what he represented, but to my young eyes his presence didn’t warrant the thousands of fascist militia flooding Venice over recent days, let alone the crowds mustered to welcome him – some of whom we suspected had been strong-armed into their flag-waving support.

‘Popsa, why have we come here?’

I was perplexed. My grandfather was a confirmed anti-fascist and, though he kept his hatred of Mussolini largely within the family, he had nonetheless been a fierce opponent in the twelve years since ‘Il Duce’ had ruled Italy with his brigade of militarised bully boys. Quietly, at home or in the cafés with his most trusted friends, he raged over the way good Italians were being trodden on, their freedom curtailed, both morally and physically.

He bent to whisper into my ear. ‘Because, my darling Stella, I want you to see with your own eyes the enemy we will face.’

‘An enemy? But isn’t Hitler proposing to be a friend to Italy? An ally?’

‘Not to Italians, my love,’ he whispered again. ‘To good, ordinary people – Venetians like us – he is no friend. Look at him, watch his stealth – know your enemy when the time comes.’ His heavy, lined face set into a frown, and then he painted on a false smile as the militia neared, hoisting their guns to elicit a timely cheer from the crowd.

I peered at the object of their fraudulent praise, dwarfed by Mussolini’s pompous stature. I couldn’t see the distinctive face or the sharp lines of his frankly mocked hairstyle, which had dominated the newspapers in recent days. Yet the way Adolf Hitler moved among the Italian troops in the Piazza San Marco seemed almost reticent, guarded. Was this what we were supposed to be afraid of? Next to Mussolini and his army of bullies, he looked smaller in every way. Why did my big, burly and strong grandfather seem almost fearful?

Looking back on that day, Popsa’s whole demeanour was my first experience of the mask we Venetians – Italians, in fact – needed to adopt over the coming years. Behind the beautiful and glittering facade of Italy’s jewelled city, the veneer of Venice would take on Popsa’s frown, hiding its determination to maintain the real fabric of its people against Hitler and fascism.

But, back then, in my late teens, I wasn’t politicised – I was a young woman enjoying my last days at high school, relishing a summer on the beautiful beaches of the Lido, the late, low sun of endless Venetian days and perhaps the prospect of a fleeting summer romance. It was several years before I appreciated the significance of Hitler’s visit on that warm June day more than five years before war broke out, or the impact of Mussolini’s public fawning to a man who would become the devil to a good part of the world. At the dawn of war, when Italy pledged its military might alongside Hitler, I recall telling my grandfather what I later learned about that day in 1934.

‘You know what Mussolini said about Hitler on that visit?’ I asked him, pulling up the blanket over his whispery chest hair, watching his beleaguered lungs fighting the pneumonia which only days later would defeat him. ‘He called him “a mad little clown”.’

Popsa only smiled, suppressing a laugh he knew would force his lungs into a lengthy coughing fit.

He scooped in a breath. ‘Ah, but Mussolini is simply a big clown. And you know what clowns do, Stella?’

‘No, Popsa.’

‘They create havoc, my darling. And they get away with it.’

1

Grief

London, June 2017

The tears come in a torrent – great fat orbs that well up from inside her, catching momentarily on her eyelids. For a second, she feels as if she is looking through a piece of the thick, warped Murano glass dotted around her mother’s living room, until she blinks and they roll down her dried-out cheeks. Ten days into her grief, Luisa has learned not to fight it, allowing the deluge to cascade in rivers towards her now sodden chin. Jamie has helpfully placed boxes of tissues around her mother’s house; much like city dwellers are supposed to be never more than six feet from some kind of vermin, now she is never without a man-size hankie to hand.

Emotional fallout over, Luisa faces a more frustrating issue. The keyboard of her laptop has fared badly from the human cloudburst, and a glass tipped over in her temporary blindness – several of the keys are swimming in salt tears and tap water. It’s too late to mop up the flood – even a consistent jabbing of various keys tells her the screen is frozen and the machine displaying its dissatisfaction. Electronics and fluids do not mix.

‘Oh Jesus, not now,’ Luisa moans into the air. ‘Not now! Come on, Dais – work, come on girl!’ She jabs at the keyboard again, following it up with a few choice expletives, and more tears – this time of frustration.

It’s the first time she’s been able to face opening Daisy, her beloved laptop, since the day before her mum … died. Luisa wants to say the word ‘died’, needs to keep on saying it, because it’s a fact. Her mum didn’t pass away, because that somehow alludes to a serene exit, floating from one dimension to another without rancour, where there is time to put things to right amid crisp white sheets and soft blankets, to say things you want to say – need to say. Even with her limited experience of death, Luisa knows it was short, blunt and brutal. Her mum died. End of. Two weeks from first diagnosis, one week of that in a drug-induced coma to combat the unbearable pain. And now Luisa is the one enduring the inevitable ache of grief. Throw anger and frustration into the mix and you might touch on the myriad of emotions pitching and rolling around her head, heart and assorted organs, twenty-four/seven.

So, Luisa attempts what she always does when she cannot settle, eat, speak or socialise. She writes. Battle-scarred and sporting dog-eared stickers of love and identity, Daisy has been a reliable friend to Luisa in her need to bleed emotions onto a screen page. Often, it’s nothing more than crazy ramblings, but occasionally there is something of worth amid the jumble of words – a sentence or string of thought she might squirrel away for future use or that might well make it into the book one day. The book she will write when she is free of the inane meanderings she currently commits to the features pages of various magazines about the very latest thing in cosmetics, or whether women really do want to steer their own destiny (of course they do, she thinks as she writes – do I really need to spell it out in no more than a thousand words?). But it’s work. It keeps the wolf from the door while Jamie establishes himself as a jobbing actor. But one day the book will happen.

Daisy is party to this dream, a workmate and a keeper of secrets too, deep down in her hard drive.

‘Christ Daisy, what happened to loyalty, eh?’ Luisa mutters, and then feels immediately disloyal to her hi-tech friend. Half drowned in human tears, she may well have reacted in the same way and refused to go on. Daisy needs TLC and time to dry out on top of the boiler. In the meantime, there are pent-up emotions to spill – and for some inexplicable reason a pen and paper is not up to the job. Luisa feels the need to hit something, to bash and clatter at the keys and watch the words appear on screen as if they have magically appeared from somewhere deep inside her, separate to her conscious thinking. Being a child of the computer age, and with her grief threatening to spew, a pen will simply not allow those words to explode from her with venom or unbounded love, or the anger that she cannot contain.

A thought strikes her: Jamie had been up in her mother’s attic the day before to assess just how much clearing out lay ahead of them. As Luisa was tackling the cancelling of direct debits and council tax, he mentioned seeing a typewriter case tucked in the eaves, one that looked fairly old but ‘in good nick’. Would it be worth anything? Or was it sentimental value, he’d asked. At the time, she dismissed it as non-urgent but now her need is greater.

The loft space is like a million others across the globe: a curious odour of old lives dampened and dust that flies up with irritation as you disturb its years of slumber. A single light bulb hangs from the timbers, and Luisa needs to adjust her eyes before objects come into focus. She recognises a few Christmas presents she took pains to choose for her mother – a thermostatic wrap for her aching back and a pair of sheepskin slippers – both of which look to have been barely out of their wrappers before being abandoned to the ‘Not Wanted’ pile. Another reminder of the distance between mother and daughter, now never to be bridged. She pushes the memory away – it’s too deep inside her for now, though it constantly threatens to push through into her grief. It’s therapy for another day. Luisa ferrets around for a few minutes, feeling her frustration rise and wondering if this is the best pastime at this moment, when things still feel so raw. She both relishes and dreads finding a family album where she knows she won’t be able to stop herself from turning the dog-eared pages of so-called happy memories. All three of them on the beach – her, Mum and Dad – fixed Kodachrome smiles all round. In better days.

Mercifully, an object that is not a fat bound book of memories pushes its way out of the gloom. Instead, it’s a grey, moulded case whose shape – square and sloping towards a brown leather handle – means it can only be one thing. It has the look of a life well worn, the scuffs and scratches immediately reminding her of the history Daisy sports on her own casing. There is a distinctive twang as both clasps spring upwards under Luisa’s fingers, and what almost sounds like the escape of a human breath as she lifts the lid. Even under the dim light, she can see it is beautiful – a monochrome mix of black and grey, white keys ringed with a dull metal and glowing bright against the dimness. Luisa puts a tentative finger on one of the keys, pressing it gently, and the mechanism reacts under her touch, sending a thin metal shaft leaping towards the roller. It hasn’t seized up. She notes, too, that there is a ribbon still attached and, even better, a spare, sealed reel tucked alongside the keyboard. The aged cellophane is intact but almost disintegrates under her finger. If fate is on her side, however, the ribbon won’t have dried up.

Luisa fixes the lid back down and pulls the case away from a pile of boxes – it’s surprisingly light for an old machine. As she pulls, the lid on one of the boxes slides off, sending a puff of dust in its wake. She turns to replace it, but her eye catches a single photograph, black and white yet sepia-toned with age. It features a man and a woman – their joyful expressions suggest a couple – standing in St Mark’s Square in Venice, the distinctive grandiose basilica behind them, surrounded by a groundswell of pigeons. She recognises her mother in the features of the woman, but not the man. Luisa searches her memory – did her mother and father even mention going to Venice, perhaps for their honeymoon? It looks that kind of photo – the couple seem happy. It’s not how she remembers her parents, but she thinks even they must have been in love once. And yet the photo looks older than that, from a bygone age.

Luisa is aware of her Italian roots, the spelling of her name being an obvious indication. Both of her mother’s parents were Italian, but they died some years ago; her grandfather when she was just a baby, and grandmother in her early teens. She knows very little about their history – her mother would never talk about it – except that they were both writers. She likes to think she has inherited at least that family trait from them.

She flips over the photograph; scrawled in pencil are the words ‘S and C, San Marco June 1950’. Her mother was Sofia, but she was born in 1953, so maybe it’s her grandmother’s face beaming contentment? S for Stella? Perhaps that’s Luisa’s grandpa standing alongside her – Luisa barely remembers him, only a fleeting image of a kindly face. But his name was Giovanni. So who is C? It’s entirely possible he was a suitor before Grandpa Gio, as she knows they called him. Luisa’s curiosity gives way to a smile, her first in days, and the movement of the muscles feels odd. She thinks they look so stylish, he in his high-waisted suit trousers, and she in a neat Chanel-like suit and elegant court shoes, her hair swept in a chic, black wave.

Luisa bends to replace the photograph in the box, but sees that underneath a decaying layer of tissue paper there is more – photographs and paper scraps, some hand-scribed and others typed in an old font, perhaps on the newly discovered machine? To any other curio browser it would warrant a look at the very least, but to a journalist it spikes the senses. There is something about the smell too – the pungency of old dust – which sticks in Luisa’s nostrils and makes her heart beat faster. It reeks of lives lived and history unmasked.

The whole box is heavy and awkward to manoeuvre down the attic stairs and into the living room. In the daylight however, she sees the real treasure come to light. Under a layer of loose type and several browned, brittle newspapers bearing the name Venezia Liberare, Luisa can sense it: a mystery. It’s in the fine sandy texture under her fingers as she gingerly lifts the paper cache – men and women grinning in fuzzy tones of black and white, some she notes casually using rifles as props, or proudly holding them across their chests, women included. Momentarily, she is shocked; in a distant memory, her grandma never appeared as anything other than that – a sweet old lady who dished out cuddles and chocolates, grinning mischievously when she was inevitably rebuked by Luisa’s mother for spoiling her with sweets. Sometimes, Luisa remembers her slipping little wrapped bars when no one was looking, whispering ‘Shh, it’s just our secret’, and she felt like they were part of a little gang.

The typewriter is momentarily forgotten as Luisa picks up each piece, peering at its faded detail, squinting to fill in the gaps of pencil scratchings lost to the years. It hits her squarely then – how many people’s histories are contained in this cardboard box with its sunken edges and corners gnawed at by the resident mice? What might she discover in its depths amid the deceased spiders and smell of mould? What will she learn about her family? She wonders, too, if there is an element of fate in her discovery, if today of all days she was meant to find it – to piece it all together in some order, and in turn glue her recently shattered self back together. For the first time in weeks, she feels not defeated or leaden with grief, but lifted a little. Excited.

2

The Lion’s Den

Venice, early December 1943