Полная версия

Dawnspell

KATHARINE KERR

Dawnspell

The Bristling Wood

For the profit of kins, well did he attack the hosts of the

country, the bristling wood of spears, the grievous

flood of the enemy…

The Gododdin of Aneirin, Stanza A84

Copyright

Voyager An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.voyager-books.com

Previously published in paperback by Grafton 1990 reprinted six times and by HarperCollins Science Fiction & Fantasy 1993 reprinted two times

First published in Great Britain by GraftonBooks 1989

Copyright © Katharine Kerr 1989

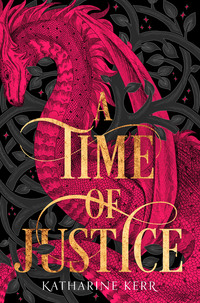

Cover design and illustration by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © July 2019 ISBN 9780007404384

Version: 2019-07-15

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Epigraph

In memoriam

Raymond Earle Kerr, Jr, 1917–87,

an officer and a gentleman

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

Epigraph

A Note on the Pronunciation of Deverry Words

Prologue: Spring, 1063

Part One: Deverry and Pyrdon, 833–845

1

2

3

4

Part Two: Summer, 1063

1

2

3

Appendix

Keep Reading

Glossary

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

A Note on the Pronunciation of Deverry Words

The language spoken in Deverry is a member of the P-Celtic family. Although closely related to Welsh, Cornish, and Breton, it is by no means identical to any of these actual languages and should never be taken as such.

Vowels are divided by Deverry scribes into two classes: noble and common. Nobles have two pronunciations; commons, one.

A as in father when long; a shorter version of the same sound, as in far, when short.

O as in bone when long; as in pot when short.

W as the oo in spook when long; as in roof when short. Y as the i in machine when long; as the e in butter when short.

E as in pen.

I as in pin.

U as in pun.

Vowels are generally long in stressed syllables; short in unstressed. Y is the primary exception to this rule. When it appears as the last letter of a word, it is always long, whether that syllable is stressed or not.

Diphthongs generally have one consistent pronunciation:

AE as the a in mane.

AI as in aisle.

AU as the ow in how.

EO as a combination of eh and oh.

EW as in Welsh, a combination of eh and oo.

IE as in pier.

OE as the oy in boy.

UI as the North Welsh wy, a combination of oo and ee. Note that OI is never a diphthong, but is two distinct sounds, as in carnoic (KAR-noh-ik).

Consonants are mostly the same as in English, with these exceptions:

C is always hard as in cat.

G is always hard as in get.

DD is the voiced th as in thin or breathe, but the voicing is more pronounced than in English. It is opposed to TH, the unvoiced sound as in breath. (This is the sound that the Greeks called the Celtic tau.)

R is heavily rolled.

RH is a voiceless R, approximately pronounced as if it were spelled hr in Deverry proper. In Eldidd, the sound is fast becoming indistinguishable from R.

DW, GW, and TW are single sounds, as in Gwendolen or twit.

Y is never a consonant.

I before a vowel at the beginning of a word is consonantal, as it is in the plural ending -ion, pronounced yawn.

Doubled consonants are both sounded clearly, unlike in English. Note, however, that DD is a single letter, not a doubled consonant.

Accent is generally on the penultimate syllable, but compound words and place-names are often an exception to this rule.

I have used this system of transcription for the Bardekian and Elvish alphabets as well as the Deverrian, which is, of course, based on the Greek rather than the Roman model. On the whole it works quite well for the Bardekian, at least. As for Elvish, in a work of this sort it would be ridiculous to resort to the elaborate apparatus by which scholars attempt to transcribe that most subtle and nuanced of tongues. Since the human ear cannot even distinguish between such sound-pairings as B> and B<, I see no reason to confuse the human eye with them. I do owe many thanks to the various elven native speakers who have suggested which consonant to choose in confusing cases and who have laboured, alas, often in vain, to refine my ear to the elven vowel system.

A Note on Dating

Year One of the Deverry calendar is the founding of the Holy City, or, to be more accurate, the year that King Bran saw the omen of the white sow that instructed him where to build his capital. It corresponds roughly to 76 CE.

Prologue Spring, 1063

Often those who study the dweomer complain that it speaks in riddles. There is a reason for this riddling. What is it? Well, that happens to be a riddle of its own.

The Secret Book of Cadwallon the Druid

Out in the grasslands to the west of the kingdom of Deverry, the concepts of ‘day’ and ‘month’ had no meaning. The years flowed by, slowly, on the ebb and swell of the seasons: the harsh rains of winter, when the grass turned a bluish-green and the grey sky hung close to the earth; the spring floods, when the streams overflowed their banks and pooled around the willows and hazels, pale green with first leaves; the parching summer, when the grass lay pale gold and all fires were treacherous; the first soft rains of autumn, when wildflowers bloomed briefly in purple and gold. Driving their herds of horses and flocks of sheep, the People drifted north in the summer’s heat and south in the winter’s cold and, as they rode, they marked only the little things: the first stag to lose its antlers, the last strawberries. Since the gods were always present, travelling with their folk in the long wandering, they needed no high holidays or special feasts in their honour. When two or three alarli, the loosely organized travelling groups, happened to meet, then there was a festival to celebrate the company of friends.

Yet, there was one day of the year marked out from all the others: the spring equinox, which usually signalled the start of the floods. In the high mountains of the far north, the snows were melting, sending a tide down through the grasslands, just as another tide, this one of blood, had once swept over them from the north in the far past. Even though individuals of their race lived some five hundred years on average, by now there were none left who’d been present in those dark years, but the People remembered. They made sure that their children would always remember on the day of the equinox, when the alarli gathered in groups of ten or twelve for the Day of Commemoration.

Even though he was eager to ride east to Deverry, Ebañy Salomonderiel would never have left the elven lands until he’d celebrated this most holy and terrifying of days. In the company of his father, Devaberiel Silverhand the bard, he rode up from the sea-coast to the joining of the rivers Corapan and Delonderiel, near the stretch of primeval forest that marked the border of the grasslands. There, as they’d expected, they found an alardan, or clan-meet. Scattered in the tall grass were two hundred painted tents, red and purple and blue, while the flocks and herds grazed peacefully a little distance away. A little apart from the rest stood ten unpainted tents, crudely stitched together from poorly tanned hides.

‘By the Dark Sun herself,’ Devaberiel remarked. ‘It looks like some of the Forest Folk have come to join us.’

‘Good. It’s time they got over their fear of their own kind.’

Devaberiel nodded in agreement. He was an exceptionally handsome man, with hair pale as moonlight, deep-set dark blue eyes, slit vertically like a cat’s, and gracefully long pointed ears. Although Ebañy had inherited the pale hair, in other ways he took after his mother’s human folk; his smoky grey eyes had round irises, and his ears, while slightly sharp, passed unnoticed in the lands of men. They rode on, leading their eight horses, two of which dragged travois, loaded with everything they owned. Since Devaberiel was a bard and Ebañy a gerthddyn, that is, a storyteller and minstrel, they didn’t need large herds to support themselves. As they rode up to the tents, the People ran out to greet them, hailing the bard and vying for the honour of feeding him and his son.

They chose to pitch the ruby-red tent near that of Tanidario, a woman who was an old friend of the bard’s. Although she’d often given his father advice and help as he raised his half-breed son alone, Ebañy found it hard to think of her as a mother. Unlike his own mother back in Eldidd, whom he vaguely remembered as soft, pale and cuddly, Tanidario was a hunter, a hard-muscled woman who stood six feet tall and arrow-straight, with jet-black hair that hung in one tight braid to her waist. Yet when she greeted him, she kissed his cheek, caught his shoulders, and held him a bit away while she smiled as if to say how much he’d grown.

‘I’ll wager you’re looking forward to the spring hunt,’ he said.

‘I certainly am, little one. I’ve been making friends with the Forest Folk, and they’ve offered to show me how to hunt with a spear in the deep woods. I’m looking forward to the challenge.’

Ebañy merely smiled.

‘I know you,’ Tanidario said with a laugh. ‘Your idea of hunting is finding a soft bed with a pretty lass in it. Well, maybe when you’re fully grown, you’ll see things more clearly.’

‘I happen to be seventy-four this spring.’

‘A mere child.’ She tousled his hair with a calloused hand. ‘Well, come along. The gathering’s already beginning. Where’s your father got to?’

‘He went with the other bards. He’ll be singing right after the Retelling.’

Down by the river, some of the People had lashed together a rough platform out of travois poles, where Devaberiel stood conferring with four other bards. All around it the crowd spread out, the adults sitting cross-legged in the grass while restless children wandered around. Ebañy and Tanidario sat on the edge near a little group of Forest Folk. Although they looked like the other elves, they were dressed in rough leather clothes, and each man carried a small notched stick, bound with feathers and coloured thread, which were considered magical among their kind. Although they normally lived in the dense forests to the north, at times they drifted south to trade with the rest of the People. Since they had never been truly civilized, the events that they were gathered to remember had spared them.

Gradually the crowd quieted, and the children sat down by their parents. On the platform four bards, Devaberiel among them, took their places at the back, arms crossed over their chests, legs braced a little apart, a solemn guard of honour for the storyteller. Manaver Contariel’s son, the eldest of them all, came forward and raised his arms high in the air. With a shock, Ebañy realized that this would be the last year that this bard would retell the story. He was starting to show his age, his hair white and thin, his face pouched and wrinkled. When one of the People aged, it meant death was near.

‘His father was there at the Burning,’ Tanidario whispered.

Ebañy merely nodded his acknowledgement, because Manaver was lowering his arms.

‘We are here to remember.’ His highly trained voice seemed to boom out in the warm stillness.

‘To remember,’ the crowd sighed back. ‘To remember the west.’

‘We are here to remember the cities, Rinbaladelan of the Fair Towers, Tanbalapalim of the Wide River, Bravelmelim of the Rainbow Bridges, yea, to remember the cities, and the towns, and all the marvels of the far, far west. They have been taken from us, they lie in ruins, where the owls and the foxes prowl, and weeds and thistles crack the courtyards of the palaces of the Seven Kings.’

The crowd sighed wordlessly, then settled in to listen to the tale that some had heard five hundred times or more. Even though he was half a Deverry man, Ebañy felt tears rise in his throat for the lost splendour and the years of peace, when in the hills and well-watered plains of the far west, the People lived in cities full of marvels and practised every art and craft until their works were so perfect that some claimed them dweomer.

Over a thousand years ago, so long that some doubted when the Burning had begun, whether it was a thousand and two hundred years or only a thousand and one, several millions of the People lived under the rule of the Seven Kings in a long age of peace. Then the omens began. For five winters the snows fell high; for five springs, floods swept down the river. In the sixth winter, farmers in the northern province reported that the wolves seemed to have gone mad, hunting in big packs and attacking travellers along the road. The sages agreed that the wolves must have been desperate and starving, and this, coupled with the weather, meant famine in the mountains, perhaps even some sort of blight or plague that might move south. In council the Seven Kings made plans: a fair method of stockpiling food and distributing it to those in need, a small military levy to deal with the wolfpacks. They also gathered dweomerfolk and sages around them to combat the threats and to lend their lore to farmers in need. In the sixth spring, squadrons of royal archers went forth to guard the north, but they thought they were only hunting wolves.

When the attack came, it broke like an avalanche and buried the archers in corpses. No one truly knew who the enemies were; they were neither human nor Elvish, but a squat breed like enormous dwarves, dressed in skins, and armed only with crude spears and axes. For all their poor weapons, their warriors fought with such enraged ferocity that they seemed not to care whether they lived or died. There were also thousands of them, and they travelled mounted. When the sages rushed north with the first reinforcements, they reported that the language of the Hordes was utterly unknown to them. Half-starved, desperately fleeing some catastrophe in their homeland, they burned and ravaged and looted as they came. Since the People had never seen horses before, the attackers had a real advantage, first of surprise, then of mobility once the elves grew used to the horrifying beasts. By the time they realized that horses were even more vulnerable to arrows than men, the north was lost, and Tanbalapalim a heap of smoking timbers and cracked stone.

The kings rallied the People and led them to war. After every man and woman who could loose a bow marched north, for a time the battles held even. Although the corpse-fires burned day and night along the roads, still the invaders marched in under the smoke. Since he pitied their desperation, King Elamanderiel Sun-Sworn tried to parley with the leaders and offered them the eastern grasslands for their own. In answer, they slew his guard of honour and ran his head on to a long spear, which they paraded in front of their men for days. After that, no mercy was offered. Children marched north with bows to take the places of their fallen parents, yet still the Hordes came.

By autumn the middle provinces were swept away in a tide of blood. Although many of the People fell back in a last desperate attempt to hold Rinbaladelan on the coast, most fled, taking their livestock, rounding up the horses that had given the invaders such an edge, loading wagons and trekking east to the grasslands that the Hordes despised. Rinbaladelan fought out the winter, then fell in the spring. More refugees came east, carrying tales the more horrible because so common. Every clan had had its women raped, its children killed and eaten, its houses burned down around those too weak to flee. Everyone had seen a temple defiled, an aqueduct mindlessly toppled, a farm looted then burned instead of appropriated for some good use. All summer, refugees trickled in – and starved. They were settled folk, unused to hunting except for sport. When they tried to plant their hoarded seed-grains, the harsh grasslands gave them only stunted crops. Yet in a way few cared whether they lived another winter or not, because they were expecting that the enemy would soon follow them east. Some fled into the forests to seek refuge among the primitive tribes; a few reached what later became Eldidd; most stayed, waiting for the end.

But the Hordes never came. Slowly the People learned to survive by living off their flocks and herds while they explored what the grasslands had to offer them. They ate things – and still did – that would have made the princes of the Vale of Roses vomit: lizards and snakes, the entrails of deer and antelope as well as the fine meat, roots and tubers grubbed out wherever they grew. They learned to dry horsedung to supplement the meagre firewood; they abandoned the wagons that left deep ruts in the grassland that now fed them in its own way. They boiled fish-heads for glues and used tendons for bowstrings as they moved constantly from one foraging-ground to another. Not only did they survive, but children were born, replacing those killed in flash floods and hunting accidents.

Finally, thirty-two years after the Burning, the last of the Seven Kings, Ranadar of the High Mountain, found his people again. With the last six archers of the Royal Guard he rode into an alardan one spring and told how he and his men had lived among the hills like bandits, taking what vengeance they could for their fallen country and begging the gods to send more. Now the gods had listened to their grief. While the Hordes could conquer cities, they had no idea how to rebuild them. They lived in rough huts among the ruins and tried to plant land they’d poisoned. Although every ugly member of them wore looted jewels, they let the sewers fill with muck while they fought over the dwindling spoils. Plague had broken out among them, diseases of several different kinds, all deadly and swift. When he spoke of the dying of the Hordes, Ranadar howled aloud with laughter like a madman, and the People laughed with him.

For a long time there was talk of a return, of letting the plagues do their work, then slaughtering the last of the Hordes and taking back the shattered kingdom. For two hundred years, until Ranadar’s death, men gathered nightly around the campfires to scheme. Every now and then, a few foolhardy young men would ride back to spy. Even fewer returned, but those who did spoke of general ruin and disease still raging. If life in the grasslands hadn’t been so harsh at first, perhaps an army might have marched west, but every year, there were almost as many deaths as births. Finally, some four hundred and fifty years after the Burning, some of the younger men organized a major scouting party to ride to Rinbaladelan.

‘And I was among them, a young man,’ Manaver said, his voice near breaking at the memory. ‘With twenty friends I rode west, for many a time had I heard my father speak of Rinbaladelan of the Fair Towers, and I longed to see it, even though the sight might bring my death. We took many quivers of arrows, for we expected many a bloody skirmish with the last of the Hordes.’ He paused for a twisted, self-mocking smile. ‘But they were gone, long dead, and so was Rinbaladelan. My father had told me of the high temples, covered with silver and jet; I saw grassy mounds. He told of towers five hundred feet high made of many-coloured stones; I found a broken piece here and there. He told of vast processions down wide streets; I traced out the grassy tracks. Here and there, I found a stone hut, cobbled out of the ruins. In some, I found skeletons lying unburied on the floor, the last of the Hordes.’

The crowd sighed, a grief-torn wind over the grassland. Near the front a little girl squirmed free of her mother’s lap and stood up.

‘Then why didn’t we go back, if they were all dead?’ she called out in a clear, high voice.

Although her mother grabbed her, the rest of the gathering laughed, a melancholy chuckle at a child’s boldness, a relief after so much tragedy. Manaver smiled at the little girl.

‘Back to what, sweet one?’ he said. ‘The kingdom was dead, a tangle of overgrowth and ruins. We’d brought our gods to the grasslands, and the grasslands became our mother. Besides, the men who knew how to lay out fine cities and smelt iron and work in stone were all dead. Those of us who survived were mostly farmers, herdsmen, or foresters. What did we know about building roads and working rare metals?’

Her mouth working in thought, the girl twisted one ankle around the other. Finally she looked up at the dying bard.

‘And will we never go back, then?’

‘Well, “never” is a harsh word, and one that you should keep closed in your mouth, but I doubt it, sweet one. Yet we remember the fair cities, our birthright, our home.’

Even though the People sighed out the word ‘remember’ with proper respect, no one wept, because none of them had ever seen the Vale of Roses or walked the Sun Road to the temples. With a nod, Manaver stepped back to allow Devaberiel forward to sing a dirge for the fallen land. The songs would go on for hours, each bard taking a turn and singing of happier and happier things, until at last the alardan would feast and celebrate, dancing far into the night. Ebañy got up and slipped away. Since he’d heard his father practise the dirge for some months, he was heartily sick of it. Besides, his Deverry blood pricked him with guilt, as it did every year on the Day of Commemoration.