Полная версия

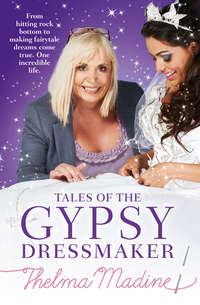

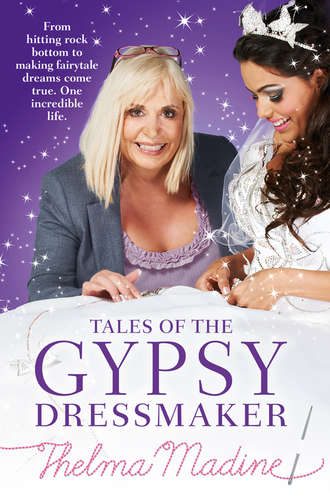

Tales of the Gypsy Dressmaker

By November I was getting loads more customers, so I thought I might start doing boys’ outfits as well, as not many people were doing them. I started to make suits with little matching caps with feathers, or with a big, droopy tassel – like an emperor’s hat. I also made old-fashioned Oliver Twist-style suits and caps. I got a reputation for doing boys’ suits then. But I have to admit that these were no ordinary suits. Seeing pictures of them now reminds me of all those nights I stayed up to get them finished in time for the market. They were so over the top, but that’s why I loved making them.

But then I’ve always loved historical costumes, especially the really old-fashioned ones that Henry VIII and Elizabeth I wore. All those big Tudor sleeves, lace collars and ruffs and things fascinated me. And anything Victorian – I just love Victorian styles.

One of my favourite things about the whole dressmaking process is going to the library to look at all the books about history and the clothes people wore in the old days. I liked the way the Little Princes in the Tower were dressed. You know, those two little boys who were locked up by their uncle hundreds of years ago. After looking at pictures of them I made these little gold, embroidered coats with little matching cravats for boys. They turned out really smart.

Of course, looking at all these old books gave me loads of new ideas, and the clothes I made were all very costume-like, I suppose, because that’s what I liked. But I do remember feeling a bit worried that the boys’ ones wouldn’t sell because they were so different from what we had been doing.

As ever, though, Dave was quick to reassure me: ‘You know what, babe, they’re brilliant.’ He said he’d never seen anything like them. Everyone knew Dave on the market then, because he used to come with me on Saturday mornings. He’d load all the stuff in his van and take me down there. But to give you an even better idea of the kind of man Dave really is – in the end he gave up his Everton season ticket to come and help me every Saturday.

Dave gave me confidence and encouraged me all the way. That felt good and it was great to have him around. Of course, he was right, I needn’t have worried: the little boys’ suits went down a storm.

I really loved doing Paddy’s Market, and I became good friends with a lot of the other stallholders and regular customers there. We’d fetch each other cups of tea and look out for each other. We were like a family.

Occasionally, the DSS or the police used to come to Paddy’s and do raids, looking for counterfeiters or people who were working while signing on. When someone heard that they were coming, word would spread through the market like a speeded-up Chinese whisper. You’d see people with dodgy DVDs and the like flying all over the place. The stalls would clear as if by magic. It was dead funny. We used to have some laughs on that market, we really did.

Just how much my Paddy’s mates would look out for me would become clearer later when I was to go through what would be one of the worst times of my life. When the going got really rough, not only did my market friends not let me down, they stuck right by me.

Things did start to get a little strained, though, when the travellers came to my stall. They’d all crowd round at once – the sister, the mother, the kids – touching things, asking things, all trying to talk to me while I worked out a price for what they wanted. It was pandemonium.

Some of the travellers who didn’t know I had a stall there, but who had seen other gypsies with the dresses, would come by and say things like, ‘Oh God, I didn’t know you were here. I’ve just given a deposit to the other woman around the corner for a dress, but I’m going to go round and get my money back.’ And they would.

I think it got up the noses of some stallholders, who didn’t seem that happy about the amount of attention I was getting. Some of them probably resented me for it. I suppose I can’t really blame them, because at times my stall would be teeming with women placing orders.

‘How much, love?’ they’d ask – usually all at once, while talking to their kids and sisters at the same time, the kids talking over them.

‘The price is on it, look, up there,’ I’d say.

But then they’d start: ‘Oh, go on, love, you can do better than that. I’m going to order three of them. I’ll give you £1,000 now, love.’

Now, I hadn’t seen £1,000 for a long time and so I’d be like, ‘Oh, all right, go on then.’

The travellers always wanted discounts. But it wasn’t just 10 per cent that they wanted off, and the same scene would be played out every time it came to the money bit. ‘I haven’t got any more money, love. Come on, that’s all I’ve got, love. Oh, go on, love.’

Before I knew it I’d be making ten dresses, so though I’d just been given £1,000, I was already out of pocket. I was making those dresses for practically nothing.

I knew I’d have to change my tune, because if I didn’t I was never going to make a profit. As it turned out I didn’t have to think about it too much, as it just happened quite naturally one Saturday. We were really busy and the stall was chaos – all these women chattering and shouting out all over the place. I thought my head was going to burst open. Only my mouth did instead.

‘That’s it!’ I screamed. ‘Nobody is getting served until you all shut up!’

‘Oh, love. Sorry, love,’ said one of the women. ‘We don’t mean any harm. We just talk loud. It’s just our way.’

They weren’t so perturbed and I realised that she was right, that was just their way, and if I wanted these women to carry on buying my dresses I’d just have to find my way of dealing with their way. From then on I got into the bargaining and even started to enjoy it. All I had to do, I learned, was stick to my guns. And it all added to the chaotic nature of the market.

Whether it was the travellers, local Liverpool girls, or the occasional raids, there was never a dull moment at Paddy’s, because if there’s one thing that flea markets throughout the world have in common, it’s great characters. And my stall was surrounded by them.

There was Baby Mary opposite me, Second-hand Mary over on one side, and Dancing Mary, who used to do all the dancing gear for kids at the back of me, and a regular at the market, Mary Hughes. Honest to God, I think they were all Marys!

Then there was Second-hand Joan. She was a real con merchant. Second-hand Joan used to borrow money from everyone but always seemed to have trouble paying it back. Second-hand Mary and Baby Mary had warned me never to lend Second-hand Joan anything.

Funnily enough, about three years ago Joan came into Nico, my shop in Liverpool that you might have seen me in when Big Fat Gypsy Weddings was on TV. She asked me if I had any old stuff that I could give her for her stall. I was happy to offload bits and bobs that we had lying around, so I went off upstairs to have a look. Joan followed me, but when we got up there I turned around and she literally fell to her knees.

‘Please help me, Thelma,’ she cried. ‘Help me. Please help me! I’ve got to pay all this money.’ She asked me to lend her £2,000. I just looked at her. It was all a bit awkward.

‘I just don’t have that kind of money to give you right now, Joan,’ I said.

‘Oh, but can you get me it? Can you get me it?’ she sobbed.

I felt sorry for her, as I knew that feeling. ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘I’ll try. But for God’s sake, get up, Joan!’

I quickly walked back downstairs. Pauline – who has been my trusty right-hand woman for as long as anyone can remember, but who no one forgets – was staring at me as we walked down. She had a look on her face that said: ‘Don’t you dare – don’t you dare trust her.’ We managed to calm Joan down a bit and got her to leave.

Then, just as if someone had written it in a play, who should walk in minutes later but Baby Mary. It was like Paddy’s Market days all over again. ‘Give her nothing,’ she said. ‘She owes so and so and so and so. She’s borrowed some money from some woman on the market and her husband has come down and said, “You get my wife’s money back now!” So now she’s come to you to get it.’

I didn’t give Joan the money – though I did think about it, because, as you’ll find out, it wasn’t that many years before that I had been in a desperate situation myself. I felt genuinely sorry for her. And I had been pleased to see her again because I used to talk to her a lot on the market.

But that night I went to the bingo with my mum and who should be sitting there playing? Joan! Yes, the woman with no money – out playing bingo! But then, you’ll always get her type on a market.

After a few months at Paddy’s, I’d kind of started to recognise the travellers from the other people at the market. One day this woman came to the stall – older than most of the traveller girls that came in – and I wasn’t sure if she was a traveller or not. She told me she had nine sons and had just had a baby girl after twenty years. She was absolutely besotted with the child.

This woman was from London, and had heard about me and our dresses, so she’d made the trip up to Liverpool with her husband to find me. That Saturday will always stick in my mind because when her husband came over he looked around the outfits on the stall and, after about four seconds, looked at me and said, ‘I’ll take the lot.’

And he did. He took every single thing I had that day that would fit the little girl. Everything. And just before they turned to leave he said, ‘I want you to make more for her because we live in London and we’re going back there. Can you make me all different ones? In different colours?’ I think I worked solidly for three weeks after that, just making dresses for that woman’s baby.

I knew that the dresses we made were special, and as the travellers used to request that more and more be added to the designs they started to look even more so. But sometimes I remember thinking while I was making them, ‘How the hell are the poor kids going to walk in these?’ I suppose, as some of them were for girls who were only around six months old, that wouldn’t be such a problem. But they were big and heavy and they really stuck out. And sometimes the little ruff necks would be stiff because I couldn’t use anything softer to make them stand up. So I’d suggest to the women that it might be a good idea to have a different design and to maybe leave out the hoop so that the baby could move a little easier.

‘I don’t think this will be very comfortable, you know, for the baby to lie in,’ I’d say.

‘No, no, love, she’ll be all right, she’ll be all right,’ they’d come back. These women were determined to have the biggest and best, regardless.

Not so long ago I was reminded of those days when I had gone to meet some English gypsies at their house, which was a massive place in Morecambe. I was a little bit apprehensive about going at first, as the travellers can be a bit wary of you if they don’t know you, and some of the Romany and English gypsies were not happy at the way they had been portrayed on the TV programme. So I was thinking, ‘Oh, we’re going to get a right reception here.’

But when we walked in they were all just so happy to see me. Pauline and me got chatting to them and one of the young girls came up to me and said: ‘I’ve got a dress you made for me when I was four. Do you remember?’ I couldn’t, because she must have been about sixteen or seventeen by this time. ‘Have you still got it?’ I asked. So she ran upstairs and brought down this little brown and ivory velvet dress.

At that point her dad walked in and said, ‘Do you remember we came to your house on Christmas Eve to pick it up?’

‘God,’ I said. ‘Yeah, I do remember that!’ It was about thirteen years ago. ‘Bloody hell,’ I thought, looking at that dress again. It was still in perfect condition, still in its bag and everything. It was short and sticky-out, made in velvet panels that were all braided around the edge, and it had a little coat that went over it, with a tiny muff and a beret. I had seen that outfit on a woman in a book about the 1800s and then made my own little version of it.

When I looked at that dress it brought back all these really happy memories of that time at Paddy’s in the late 1990s and how everything had started to pick up with those little Gone With the Wind dresses. They really were sweet.

I suppose my original Victorian designs look a bit dated now, when you think about the requests we get for Communion dresses these days, with their giant skirts, hundreds of ruffles, miles of material and all the glittery crystals and crowns, and the kids turning up to church in their own pink limos. And I couldn’t be happier doing all the fantastic and elaborate designs that we are asked for today, but I do have fond memories of making these early designs, of being so determined to get them right, so that all these gorgeous little kids would look like characters out of a film, all perfectly pretty. And I’m dead chuffed when my long-standing traveller customers want to pull them out and show me those early ones again. Luckily, my English and Romany customers still like to dress their kids in these romantic old styles, so I do still get a chance to make them.

By the end of that first year on the market I’d got to know a little bit more about the travellers’ ways; I suppose I’d started to accept their way of doing things and was becoming less surprised that travellers’ lives weren’t much like mine. But a memory that still really sticks in my mind was of a little girl hanging about the stall in December. She was looking at the dresses while her mum was settling up for orders and she was chattering away about how they were all going to meet on Christmas Day and Boxing Day. Then she said something about them all being in their trailers. It had never actually occurred to me that gypsies still lived in caravans.

‘Bloody hell,’ I thought, ‘how are you all going to get round the Christmas table in a caravan with these dresses on?’ I thought of all these lovely little girls in all their lovely little velvet dresses … Then I pictured all of them covered in chocolate on Christmas Day. I didn’t feel as romantic about the whole thing after that.

But then I was exhausted. It had been a rollercoaster couple of months and I knew I needed a rest before our busiest time of the year – First Communion season, which was going to start as soon as Christmas and New Year were over.

‘Thank God it’s Christmas Eve,’ I said to Dave, when he got back from delivering our last order to a traveller site in Leeds. ‘At least they’re not going to want any of these dresses in summer …’

2

The Tale of the First Communion Dresses

My gypsy customers started coming back to Paddy’s the first few weeks in January. Only now they were coming from all over the country, not just Liverpool or Manchester but from London and Ireland too. As I was getting to know them all a little better, I started giving my phone number out to some of the travellers. They had also started to talk to me more.

One Saturday, a girl approached the stall with a pram. She had a big black coat on and was wrapping it tightly around her. The coat seemed huge because she was tiny. She was very, very young, and, to be honest, looked like she had the world on her shoulders. She kind of shuffled up.

‘Are you the Liverpool woman who makes the dresses?’ she asked, softly. ‘I want dresses made for two little girls,’ she said, pointing to the pram.

I looked down and saw these two tiny little things. One looked around twelve months old, the other a newborn baby. ‘I want them really sticking out.’ And then I want this, and I want that, the young girl carried on. She said that she wanted a bonnet for the really tiny one, who I noticed, when I looked in at her properly, was so small that she looked premature.

‘I’m not sure that the dresses are quite right for your newborn,’ I said to her.

‘Oh, she’s not newborn, she’s ten months. And she’s two,’ she said, pointing at the older baby. They really were the smallest babies I’ve ever seen.

Then the girl started asking if she could have diamonds on the dresses. Now, she was the first traveller to ask for diamonds, and as I’d never done that before I was a bit unsure. So I told her, ‘I can’t start them without half the money as a deposit.’ She said she’d go and get the money and be straight back. So off she went.

Ever since the stall had become popular with the travellers, a lot of the other stallholders had been warning me against working with them. ‘Be careful. Don’t trust them. Just don’t trust them,’ they’d say.

Surprisingly, Gypsy Rose Lee was always stressing the point. But by then I realised that she was different from them. Gypsy Rose was Romany. Romanies are wary of other travellers and, to be honest, sometimes I think they see themselves as a cut or two above them.

Gypsy Rose’s kids were around her stall all the time. They were lovely, really well-behaved, and they’d go and get us all cups of tea. The other traveller kids that came to us, on the other hand, mostly Irish, were loud and boisterous and just so full of confidence. And the language! My God, it was terrible. But I soon got used to that and realised it’s just the way they speak. It’s not threatening or anything.

So, I waited for the girl who wanted the diamond dresses to come back, and deep down I suppose I never expected to see her again – the travellers are always full of promises of coming back but quite often they don’t. But she did, and this time she had her husband in tow. He was carrying one of the babies and was smothering her in kisses. ‘What a lovely dad,’ I thought, surprised at how kind and affectionate he was being. He looked up at me and said, ‘How much are the dresses going to be?’

Now, for the tiny little baby’s outfit the girl had said that she wanted a diamond collar and diamond cuffs. She wanted diamanté all over the dresses, basically. I didn’t know a trade supplier of Swarovski crystals, so I knew I’d have to buy them at the full retail price, which would be dear.

‘£600 for the two,’ I said, thinking he’d say ‘No way’, saving me all the trouble of having to make such a tricky order.

But he didn’t even think about it. He put his hand in his pocket, flicked through the notes and handed me the cash. As they left I remember standing there thinking: ‘Jesus, I’d better make sure these dresses are really nice.’ The couple came back a few weeks later to pick them up. The young mum was over the moon.

A month or so after that I was talking to another traveller woman, Mary – Mary Connors. She was a good-looking woman, Mary, tall with long, brown, wavy hair. You could tell, just by looking at her, that she must have been stunning as a girl. By the time I got to know Mary she must have been around 35 and had had seven kids. She still had a cracking figure, though, and I always liked the way she dressed. Mary was smart and classy looking and would wear long skirts with boots, that kind of thing. She had a neat style, well-off looking, you know?

The other thing I liked about Mary was her confidence. She had an air of authority about her and I knew that she was well liked in the community. The fact that she had seven children earned her the respect of her peers, as the more children a traveller woman has the more status she gets. I always liked seeing Mary with her kids – she was a really warm person and a good mum. Her kids adored her.

But Mary was tough, and even though she was only in her mid-30s, you could tell that she had lots of experience. She was wise and taught me a lot, and would come to the stall just for a chat, asking how things were going and whether I’d had more traveller customers. When I described to her who had come in, she instantly knew who the family was and would tell me all about them. In a way Mary was educating me, teaching me more and more about the travellers that would finally make my business.

So she’d become a bit of a regular on the stall, and though we didn’t know each other really well then, we hit it off and she obviously enjoyed my company as much as I did hers, so she was always popping in for a gossip. One day she came in and asked me: ‘Did you do Margaret’s dresses for the wedding?’

‘Who’s Margaret?’ I said.

‘Margaret, you know, Sweepy’s Margaret?’

The thing is, the gypsies think that you know everyone that they do because they live in such a closed community and all know each other. But I had no idea who Margaret was. Also, in my experience all traveller women seemed to be called Margaret or Mary!

‘Oh, they were handsome, love,’ she said. ‘All these diamonds on them. Oh, they were really handsome.’

Then, of course, I knew who she was talking about.

‘Do you know him, love?’ she asked, meaning the man who’d given me the cash that day.

‘No, not really,’ I told her.

‘Oh, he’s a multi-millionaire,’ said Mary. I was gobsmacked, thinking back to the day that I first set eyes on young Margaret, remembering that black coat and how she was the poorest-looking soul I’d ever seen.

I know the family really well now. The girls in that pram are all grown up and they love the fact that they were the first to get their dresses covered in diamonds. They still talk about it.

Shannon, the two-year-old, is 16 now, and the really tiny one that I was worried about, Shamelia, is 15. They’ve got two more sisters now as well, and we have made swishy little dresses for them since they were little too. Shannon and Shamelia are a great barometer of how traveller tastes have changed. When we first started making designs for them their mum wanted all the Victorian stuff, but with lots of glitter, really pretty dresses. Now that the girls are older and have their own ideas about how they want to dress, it’s all sparkly Swarovski-covered catsuits and the like. They’ve grown up to be really gorgeous, lovely kids, these girls.

The thing is, travellers always like to dress their children well. And, you know, I think Liverpool people are exactly the same as gypsies that way, because if you don’t have much to call your own, your whole pride comes from how good your kid looks. Nothing feels better than to have your child with you, dressed up so nice that people stop and say, ‘Oh, look at what she’s wearing.’ You just want to give your kids everything. There are probably more designer kids’ boutiques in Liverpool than anywhere else today. Yet for the Liverpool mum there are never, ever enough.

I’m the same myself. About thirty years ago I bought my daughter Hayley a pair of shoes that cost around £70. To be honest, she wasn’t even at the walking stage, but I didn’t care, I just loved dressing my kids up.

A few years back, when my youngest daughter, Katrina, who’s seven now, went to nursery, all the girls who worked there used to get so excited when I dropped her off. I wasn’t on the telly then, so they didn’t know I was a dressmaker. ‘We can’t wait to see what she’s got on when she comes in,’ they’d say. So I thought, ‘Oh, I’ll definitely need to make sure I have something new on her every day if they are waiting to see what she’s wearing!’ Now I’m the same with my granddaughter Phoebe – I buy her new outfits all the time.

It’s such a Liverpool thing – maybe you need to come from Liverpool to understand it. You see, when I was a kid, no matter how little money we had, I always had the best dress and, from as far back as I can remember, I knew exactly what I wanted to wear: dream-come-true dresses that moved when you moved, dresses where you could feel the weight of the fabric swinging about you as you walked.

Once my mum asked this woman, who used to make costumes for the dancing school I went to, if she would make me a couple of day dresses. I was so excited when we went to collect them. The first one was pink with lots of frothy net under it and a big tie belt wrapped into a big bow at the side. As soon as I put that one on, I just didn’t want to take it off. I had to, though, because I had to try on the other one.