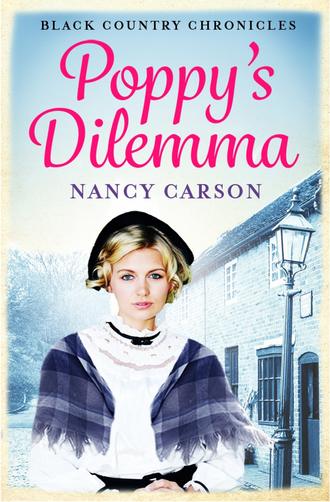

Полная версия

Poppy’s Dilemma

So the navvies slowly dispersed. They took up their picks, their shovels and their barrows, and commenced work.

Only two days before his temporary incarceration at the Dudley lock-up, Lightning Jack had spoken to a navvy who had passed through the Blowers Green workings on tramp. The man had been looking for good, dry tunnelling work and had been disappointed to discover that the Dudley tunnel had already been completed. He’d told Lightning that he’d been working on the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton at Mickleton, but had got into trouble with a card school to whom he owed some unpaid gambling debts, so he’d sloped off. Recalling what this man had told him, Lightning decided to head south and try his luck at Mickleton. That first Saturday, he walked about twenty miles and was refreshed and victualled at a public house in Ombersley, Worcestershire.

Afterwards, he found a suitable hedge under which to sleep, the weather being settled. Next morning, he awoke under a blue sky and took in a great gulp of the cool morning air, so fresh with the promise of summer, and free of the stench of coal gas that had normally greeted him at Blowers Green. The sight of the leaves stirring gently on the trees, and of the ordered pattern of fields that adorned the landscape, set his heart singing after the muck and filth of the Black Country. Maybe he should have gone on tramp before. He finished what food he had in his pantry, gathered his things together and set off again, intent on reaching Mickleton later that day. At Evesham, stopping for a gallon of ale at a beer shop, he met another navvy on tramp and they got talking. The stranger told Lightning that people knew him as ‘Bilston Buttercup’.

‘I’ve never seen anybody less like a buttercup in all me life,’ Lightning said, genially, as they supped. ‘Buttercups are pretty, dainty flowers. You’m as plain as a pikestaff and as ungainly as a three-legged donkey.’

The stranger laughed good-heartedly at Lightning’s banter. ‘That I am, and no doubt about it. Here … fill thy gum-bucket with a pinch or two o’ this best baccy.’

‘Ta …’ Lightning helped himself to some of the tobacco the man was offering and filled his clay pipe. ‘So you’re a Bilston bloke, eh?’

‘Bilston born and bred,’ the plain man said, filling his own gum-bucket. ‘Though I’ve been most places.’

‘So where are you heading for now?’ Lightning asked.

‘The Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton. They say there’s work on the Mickleton tunnel near Campden.’

‘That’s where I’m headed. We might as well tramp there together, if that’s all right by you.’

‘Let’s have a drink or three together and celebrate the fact,’ suggested Buttercup.

So Lightning Jack and Bilston Buttercup drank. They drank so much that they lost their resolve to reach Mickleton and, instead, discussed where they would doss down that night.

‘Under the stars,’ declared Lightning. ‘There’s nothing like it, and the weather’s fair.’

‘Then maybe we should find somewhere afore darkness falls. We can always find an inn afterwards for a nightcap.’

So they finished their drinks and set off in search of a place to sleep, into countryside that was wearing its vivid green May mantle. They pitched camp just outside a village called Wickhamford, alongside a stream that was invitingly clear. Buttercup contemplated building himself a sod hut, constructed by cutting turf from the ground and stacking it into walls, to be roofed with a tarpaulin.

‘So where’s your tarpaulin?’ Lightning enquired.

‘Oh, bugger!’ Bilston Buttercup replied with a laugh of self-derision. ‘I ain’t got ne’er un, have I? Damn it, I’ll sleep in the open … Like yo’ say, Lightning, the weather’s fair. Tell thee what – I’ll go and catch us our dinner. Why doesn’t thou gather some wood and kindle us a fire, eh?’

Lightning did what his new friend suggested. He collected some dry sticks of wood and had a respectable fire going in no time. He carried in his pantry a small round biscuit tin in which he kept his mashings, which was tea leaves mixed with sugar and wrapped in little parcels of paper screwed together at one end. From the stream, he filled this biscuit tin with fresh spring water and set it over the fire to boil. He stood up and stepped back to admire the fire. In an adjoining field he could hear the lowing of cows and knew at once where to get his milk. He took his metal tea bottle, rinsed it in the stream, and clambered through the hedge that surrounded the field. Startled rabbits bolted before him, but the cows regarded him with that indifferent curiosity of which only bovines are capable as he strutted towards them. Already he had picked his cow, its udders bulging.

‘Here, come to daddy,’ he said softly and stooped down alongside the compliant animal. As Lightning returned to the campfire with his bottle of fresh warm milk, he saw that Buttercup had arrived back also, and was feathering a chicken.

‘Bugger’s still nice and warm,’ he said. ‘Feel.’ Lightning felt. ‘There’s another, yon, for thee.’ Buttercup gestured his head towards the ground behind him. By the flickering light of the fire, Lightning could just make out another chicken lying forlornly dead, its neck broken.

‘Feather it, and I’ll draw the innards out for thee,’ Buttercup offered.

‘Where did you pinch these from?’ Lightning asked, collecting the chicken from the ground.

‘Some farm, yon. I picked up some eggs as well.’

‘Let’s hope no bugger heard you or saw you,’ Lightning said, recalling his brief stay in Dudley gaol for allegedly stealing something of similar value.

When the men had finished plucking feathers, Buttercup drew the innards out of both chickens and washed the hollow carcasses in the stream. Lightning constructed a spit from wood, on which they could cook the two fowls over the fire. Meanwhile the water in the little tin was steaming promisingly. Lightning watched his companion’s face by the light of the flickering fire as he rammed the chickens on the spit and began cooking them.

‘What brings you on tramp?’ Buttercup asked his companion.

Lightning Jack filled and lit his gum-bucket and told his story. ‘But it’s hard to leave a woman and kids. It is for me, at any rate. Some buggers couldn’t give a toss, but I think the world o’ my Sheba. I shall send for her and my babbies just as soon as I got meself settled at Mickleton. What about you, Buttercup?’

‘Me? I’m single, me.’ Buttercup turned the chickens on the spit and the fire crackled as it was fuelled with a further sputtering of fat. ‘I wouldn’t be in thy shoes, tied to a woman’s apron strings all thy natural. I’ve seen it all afore, watched men and women and seen how as they make each other as miserable as toads in a bag of flour. Look at another woman and just see how they moan. They swear as yo’m having it off. Dost ever look at other women, Jack?’

‘That I do. Show me a bloke as don’t and I’ll show you an elephant that can purr like a kitten.’

‘How old is your old woman, Jack?’

‘Not so old. Thirty-one. And not bad looking, considering she’s had seven. Two of ’em died, though, Buttercup.’

‘Aye, well when she’s forty-one her teeth’ll very likely fall out and all her hair. Then you’ll be gawping at even more women … younger women … and wondering why on earth thou ever messed with her in the fust place.’

‘Well, she was a right pretty young thing when we jumped the broomstick,’ Lightning said. ‘Fourteen, she was, and pretty as a picture. I was about nineteen.’

‘Aye,’ replied Buttercup. ‘But, by God, how quick they go to seed. The time will come when thou would’st rather kiss a scabby hoss.’

Lightning laughed. ‘Who knows? Mebbe …’ The water in the tin began bubbling. ‘I’ll drum up.’ His pipe clenched between his teeth, he poured some of it into his metal bottle and followed it with his mashings.

‘Just think,’ Buttercup said. ‘You and that Sheba o’ thine have got nothing to look forward to now but the workhouse or the grave.’

‘That’s it, cheer me up,’ Lightning said. ‘And what have you got to look forward to?’

‘Whatever I set me mind on,’ came the reply. ‘And if I want e’er a woman, I’ll have one, without it laying on me conscience.’

‘Have you never loved a woman, Buttercup?’

‘Oh, aye, to be sure. When I was younger and a lot safter than I bin now.’

‘Have you ever thought what it’d be like to have a little house o’ your own? To have the woman you love bring you your dinner on your own best bone china while you was warming your shins in front of a blazing fire?’

‘Oh, aye,’ Buttercup replied. ‘I was close to it once. Sadie Visick was her name. Met her while I was working once diggin’ up Wiltshire. Any road, I put Sadie in the family way …’

‘Then what?’ Lightning asked. ‘What steps did you take?’

‘Bloody big steps. I bloody well hopped it, sharp. I couldn’t see meself tethered down by e’er a wench and a screaming brat. Any road, as a navvy, what chance hast thou got o’ living a decent life? All around it’s dirty and depraved. Filthy, unkempt men like me and thee, Lightning, wi’ no money, one shirt to we name and a pair of boots what leak like a cellar in a flood. When was the last time you ever saw a priest?’

‘You mean one o’ the billycock gang?’

‘Aye. Some churchman who’d have a good try at saving thy soul, putting thee on the straight and narrow?’

Lightning shrugged. ‘Dunno if I want to see any o’ them stuck-up bastards. Dunno if I believe in God, to tell you the truth, Buttercup. I’d rather there was no God. If He’s keeping a tally on me and my misdeeds, I’ve got a fair bit of accounting to do come judgement day.’

‘Aye, me an’ all,’ Buttercup confessed. ‘Like I said, I never did right by Sadie Visick, though her was comely enough and pleasant with it. I wonder whether her had a little chap or a wench …’

‘Does it matter after all them years?’ Lightning commented. ‘It’s history now.’

Eventually, the chickens were cooked. The two navvies ate well and drank their hot tea, talking ceaselessly. So engrossed were they in their conversation that they stoked up the fire and their gum-buckets and talked into the night, never once thinking about beer. Tired, they eventually fell into a contented silence, firm friends, and slept soundly on the ground till daylight, awaking to air that was as full of the sounds of spring as it was of perfume. The ardent songs of nesting birds was as strange to both men’s ears as the whisper of water from the stream as it lapped over the stones and gravel of its bed.

They rekindled the fire and Lightning fried the eggs Buttercup had stolen in a bit of fat left over from the chicken, using his shovel as a frying pan. While they ate, they consulted the dog-eared map that Buttercup pulled out of his pantry, and pored over it.

‘Why … Mickleton’s no distance, judgin’ by this,’ Buttercup said, looking up from the map. ‘We’ll be there by drumming up time. I just wish I could read the blasted thing.’

Chapter 3

According to the navvies’ convention for nicknaming, anybody who was short and stocky was liable to be called ‘Punch’. But, to differentiate between the several Punches inevitably working together on the same line, they had to be further identified by some other pertinent feature. Thus, Dandy Punch was so named because of his taste in colourful and fancy clothes, as well as for his stockiness. He was about forty years old as far as anyone was able to guess, but he might have been younger. He was employed by Treadwell’s, the contractors, as a timekeeper, and one of his tasks on a Saturday was to collect rent from those workers who occupied the company’s shanty huts as tenants. Lightning Jack had been gone a week when he called on Sheba.

Poppy answered his knock and stood barefoot at the door of the hut, her fair hair falling in unruly curls around her face. Her eyes were bright, but they held no regard for Dandy Punch.

‘Rent day again,’ he said, a forced smile pinned to his broad face. His eyes lingered for a second on the creamy skin of Poppy’s slender neck as he tried to imagine the places covered by her clothing. ‘Comes around too quick, eh? But never too quick to see you, my flower. Heard from your father?’

Poppy shook her head.

‘Well, no news is good news. Is your mother here?’

Sheba had lingered behind the door, and thrust her head around it when she was summoned. ‘You’ve come about the rent … As you know, Lightning Jack has made himself scarce. He asked me to say that if you could put the rent down as owing … he’d look after you when he got back.’

‘When’s he coming back?’ Dandy Punch asked.

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know, eh? Has he jacked off for good?’ He arched his unpitying eyebrows and fumbled with the thick ledger he was carrying, which bore the records of what was owed.

‘No, he’s coming back. For certain. I just don’t know when.’

Dandy opened his book, licked his forefinger and thumb and flipped through the handwritten pages unhurriedly. ‘He already owes a fortnight’s rent. Ain’t you got no money to pay it?’

Sheba shook her head. ‘He said you’d be able to cover it somehow, till he got back. As a favour.’

His eyes strayed beyond Sheba, into the hut, drawn by the sight of Poppy. She was pulling on a stocking as she sat on a chair in the shabby living room, and had pulled the hem of her skirt up above her knee. Dandy Punch tried to see up her skirt, but the dimness inside thwarted him.

‘I owe Lightning Jack no favours,’ he declared, irked. ‘D’you think you’ll be able to pay me next week?’

‘I doubt it. With Lightning away, how shall I be able to? But he’ll pay you when he gets back. He’ll have found work. He’ll have been earning.’

‘I bet you charge these lodgers fourpence a night to sleep in a bunk,’ he ventured.

‘Or a penny to sleep on the floor.’ Sheba was trying to hide her indignation. ‘But that’s got nothing to do with you. None of ’em have paid me yet for this week … or last.’

‘Well, all I can do for now is enter in me book that you owe me for this week as well. Let’s hope Lightning’s back next week so’s he can settle up.’

‘Let’s hope so,’ Sheba agreed.

Dandy Punch touched his hat, taking a last glance past Sheba at Poppy, who was pulling up the other stocking, unaware of his prying eyes.

Sheba shut the door and sat down. Her two younger daughters, Lottie and Rose, were outside playing among the construction materials stacked up in the cutting. The baby was propped up against a pillow on a bed. Poppy adjusted her garter and let the hem of her skirt fall as she stood up.

‘I wish I knew what me father was doing,’ she commented. ‘If only he could write, he could send us a letter.’

‘Even that wouldn’t do us any good,’ Sheba replied, ‘since none of us can read.’

Poppy shrugged with despondency. ‘I know.’ She grabbed her bonnet and put it on. ‘I’m going into Dudley again with Minnie Catchpole now I’ve finished me work. Can you spare me a shilling?’

‘A shilling? Do you think I’m made of money? You just heard me tell that Dandy Punch as I’d got none.’

‘Sixpence then.’

Sheba felt in the pocket of her pinafore. ‘Here’s threepence. Don’t waste it.’

A Staffordshire bull terrier scampered through the dust of the camp in front of Poppy and Minnie as they walked along the Netherton footpath towards Dudley town in the afternoon sunshine. After a morning scrubbing the wooden floor and laundering the men’s available rags, the prospect of seeing Luke once more was appealing.

‘Why didn’t you tell me you’d been seeing this Tom on the quiet?’ Poppy asked, as they began the climb to Dudley.

‘’Cause I want to keep it a secret. Dog Meat would murder me. Don’t breathe a word. Not to a soul.’

‘As if I would.’

‘And that Luke asked specially if I could bring you with me today. He took a real shine to you, you know, Poppy.’

Poppy smiled shyly. ‘He seemed decent an’ all. I liked him … But I couldn’t do with him what you do with that Tom – or with Dog Meat.’

‘Nobody’s asking you to.’

‘As long as he don’t expect me to. I see and hear enough of it with me mother and father going at it nights. It always seems as if me mother don’t like it, the way she moans. As if she’s just putting up with it to save having a row with me father. As if it’s her duty. It don’t appeal to me at all.’

Minnie burst out laughing. ‘Oh, you’ll change your mind all right once you’ve got the taste for it,’ she said. ‘Everybody does. And I’m sure your mother likes it as much as anybody.’

‘Maybe she does. Was Dog Meat the first lad you ever did it with, Minnie?’

Minnie laughed again. ‘No. I did it first with Moonraker’s son, Billy, when I was thirteen.’

‘And did you like it?’

‘Course I liked it. Else I wouldn’t have done it again. You do ask some daft questions, Poppy.’

‘But what about if you catch, Minnie? What about if you get with child?’

‘There’s ways to stop getting with child. It pays to know how if you’m going with chaps regular.’

It amazed Poppy how canny Minnie was for a girl of sixteen. She cheated on Dog Meat without a second’s thought, and he had no idea just how she was carrying on with other men.

‘Don’t you ever feel guilty?’ Poppy enquired. ‘Going behind Dog Meat’s back while he’s at work?’

‘Why should I? He’d do the same on me. He very likely does, if he gets the chance.’

Their conversation continued in the same vein until they reached The Three Crowns, where Minnie had arranged to meet Tom and Luke. The two lads were already waiting when the girls arrived. Poppy smiled bashfully at Luke and he smiled back, baring two front teeth that were black as coal.

‘It’s nice to see you again, Poppy,’ he said. ‘I didn’t really expect to, after the other Friday.’

But her eyes were fixed on his gruesome black teeth and she could not avert them. Why hadn’t she noticed those teeth before? He must not have smiled. He must have been too self-conscious of them and kept his mouth shut every time she looked his way. And besides, it had been dark when they walked down Vicar Street that night. Thank God she hadn’t kissed him. The thought of kissing him with those tarred tombstones in his mouth was repulsive. So Poppy quickly lost interest in Luke.

‘I fancy a walk round the town,’ she said experimentally, trying to extricate herself from his company. ‘I got threepence and it’s burning a hole in me pocket.’

‘I’ll come with yer,’ Luke said. ‘Tom and Minnie won’t mind being on their own together.’

She finished her drink, resigned to the idea that Luke was not going to be that easy to shake off. They walked around the town for a while until Poppy decided she really must go. Luke was uninteresting, he had little to say and, while she allowed him to walk with her as far as the gasworks, she pondered on the density of men in general and of this Luke in particular.

As Poppy walked down Shaw Road, she saw Dog Meat walking almost parallel with her below in the cutting, having just finished his shift. It was inevitable that they would meet before either reached their huts.

‘Hello, Poppy.’ He greeted her with a friendly grin that concealed his fancy for her.

‘Hello, Dog Meat. How’s the work going?’ she asked, hoping to divert him from the inevitable question about Minnie’s whereabouts.

‘It’s good,’ he answered in his thick, gruff voice. ‘I’ve bin labouring for the bricklayers … Hey, I thought you was going out with Minnie this afternoon.’

‘I had to be back early,’ Poppy lied. ‘I just left her. She’ll be back in a bit.’

The following Monday, a young navvy tramped into the encampment at Blowers Green looking for work. He was tall and lean and his broad shoulders gave no impression of the toil of carrying his wheelbarrow and tools over the miles. His very appearance was a monument to his strength and fitness. His eyes were a bluish grey with the glint of steel about them. He asked somebody to direct him to a foreman and found himself in an untidy office with Billygoat Bob, the ganger.

‘So what’s your name?’

‘They call me Jericho.’

‘Jericho what?’

Jericho shrugged. ‘Just Jericho.’

Billygoat tried to read the young man’s mind, thinking that he must be hiding his real identity for some reason, like so many of the navvies, but there was something about the lad that led him to believe he was not hiding anything. His hair was long, which meant he hadn’t been in prison recently. The name Jericho must be the only one the lad knew, but such a thing was not entirely unusual for somebody who was navvy-born.

‘I take it you’ve worked on the lines before?’ Billygoat asked.

‘Aye. I’ve been on the Leeds and Thirsk. But ’tis finished now. Afore that I worked on the Midland.’

‘What work have you been doing, lad?’

‘I done excavating, barrow-running, shaft-sinking …’

Billygoat eyed the younger man assessingly. ‘I can find you work excavating, Jericho. Your pay will be fifteen shillings a week for shifting twenty cube yards a day. Anything more will get you a bonus. Can you manage that?’

Jericho smiled. ‘I can manage twenty cube yards easy. I’ll take the job. Do you know of a hut where I can get lodgings?’

‘You’ll get a lodge over at Ma Catchpole’s.’ Billygoat pointed to a shanty that he could see from his office, and Jericho leaned forward to get a glimpse of where he should be heading. ‘They call it “Hawthorn Villa”.’ Billygoat smiled at the irony. ‘Tell the old harridan I sent you.’

‘Can you sub me a couple of bob till payday?’ Jericho asked.

‘I’ll see as you get a sub – as soon as you’ve finished your first day’s work.’

So Jericho collected his things from where he had dropped them outside and made his way over to the hut that Billygoat had pointed out. He knocked on the door and a pretty young girl with dark hair and brown eyes answered it. Her hands were wet from the work she was doing and she wiped them quickly on her apron as she smiled at him with approval.

‘Yes, what do you want?’ the girl asked, and self-consciously tucked a stray wisp of hair under her cap.

‘Is this Hawthorn Villa?’

The girl nodded. ‘That’s what everybody calls it.’

‘Good. I’m after a lodge. Billygoat told me that Ma Catchpole might have a spare bunk.’

‘Ma Catchpole is me mother,’ the girl replied. ‘I’m Minnie. Am you new here?’

‘I just got here.’ He smiled and his magnetic steel-blue eyes transfixed Minnie.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Folk call me Jericho.’

‘Jericho, eh? Well come in, Jericho.’ She stood back to allow him in and he towered above her. ‘I bet you’re thirsty after your walk. Fancy a glass of beer?’

‘I could murder a glass of beer, Minnie.’

She went over to the barrel that was standing on a stillage beneath the only window on that side of the hut and took a pint tankard, which she filled. She handed it to Jericho with an appealing smile.

‘How much do I owe you?’

‘Nothing. You can have your first pint free.’

He quaffed it eagerly and wiped his lips with the back of his hand. ‘Thanks. I don’t get a sub till I’ve finished me first shift.’

‘Then you’d better get a move on.’

Jericho emptied his tankard and handed it back to Minnie. ‘Can you show me the bunk I’ll be sleeping in?’

‘Gladly.’ She glided over the floor to the dormitory the lodgers occupied and opened the door, which creaked on its hinges. ‘That one, I think,’ she said, pointing. ‘Fourpence a night. Have you got fourpence for your first night?’

He rummaged in his pocket and pulled out a few coppers. ‘Just about.’ He handed her fourpence. ‘Where do you sleep, Minnie?’

She looked at him knowingly, then tilted her head towards the door. ‘In that bedroom there … with me mother and father and the kids …’

During the afternoon on the same day, Poppy had to go to the tommy shop owned and operated by the contractor, to buy beef, bacon, tea, condensed milk and bread. Minnie had also gone to the shop and Poppy entered just as Minnie was being served.