Полная версия

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

The Netherlands became, of course, an even greater drain upon general imperial revenues. In the early part of Charles V’s reign, the States General provided a growing amount of taxes, although always haggling over the amount and insisting upon recognition of their privileges. By the emperor’s later years, the anger at the frequent extraordinary grants which were demanded for wars in Italy and Germany had fused with religious discontents and commercial difficulties to produce a widespread feeling against Spanish rule. By 1565 the state debt of the Low Countries reached 10 million florins, and debt payments plus the costs of normal administration exceeded revenues, so that the deficit had to be made up by Spain.46 When, after a further decade of mishandling from Madrid, these local resentments burst into open revolt, the Netherlands became a colossal drain upon imperial resources, with the 65,000 or more troops of the Army of Flanders consuming one-quarter of the total outgoings of the Spanish government for decade after decade.

But the most disastrous failure to mobilize resources lay in Spain itself, where the crown’s fiscal rights were in fact very limited. The three realms of the crown of Aragon (that is, Aragon, Catalonia, and Valencia) had their own laws and tax systems, which gave them a quite remarkable autonomy. In effect, the only guaranteed revenue for the monarch came from royal properties; additional grants were made rarely and grudgingly. When, for example, a desperate ruler like Philip IV sought in 1640 to make Catalonia pay for the troops sent there to defend the Spanish frontier, all this did was to provoke a lengthy and famous revolt. Portugal, although taken over from 1580 until its own 1640 rebellion, was completely autonomous in fiscal matters and contributed no regular funds to the general Habsburg cause. This left Castile as the real ‘milch cow’ in the Spanish taxation system, although even here the Basque provinces were immune. The landed gentry, strongly represented in the Castilian Cortes, were usually willing to vote taxes from which they were exempt. Furthermore, taxes such as the alcabala (a 10 per cent sales tax) and the customs duties, which were the ordinary revenues, together with the servicios (grants by the Cortes), millones (a tax on foodstuffs, also granted by the Cortes), and the various church allocations, which were the main extraordinary revenues, all tended to hit at trade, the exchange of goods, and the poor, thus spreading impoverishment and discontent, and contributing to depopulation (by emigration).47

Until the flow of American silver brought massive additional revenues to the Spanish crown (roughly from the 1560s to the late 1630s), the Habsburg war effort principally rested upon the backs of Castilian peasants and merchants; and even at its height, the royal income from sources in the New World was only about one-quarter to one-third of that derived from Castile and its six million inhabitants. Unless and until the tax burdens could be shared more equitably within that kingdom and indeed across the entirety of the Habsburg territories, this was virtually bound to be too small a base on which to sustain the staggering military expenditures of the age.

What made this inadequacy absolutely certain was the retrograde economic measures attending the exploitation of the Castilian taxpayers.48 The social ethos of the kingdom had never been very encouraging to trade, but in the early sixteenth century the country was relatively prosperous, boasting a growing population and some significant industries. However, the coming of the Counter-Reformation and of the Habsburgs’ many wars stimulated the religious and military elements in Spanish society while weakening the commercial ones. The economic incentives which existed in this society all suggested the wisdom of acquiring a church benefice or purchasing a patent of minor nobility. There was a chronic lack of skilled craftsmen – for example, in the armaments industry – and mobility of labour and flexibility of practice were obstructed by the guilds.49 Even the development of agriculture was retarded by the privileges of the Mesta, the famous guild of sheep owners whose stock were permitted to graze widely over the kingdom; with Spain’s population growing in the first half of the sixteenth century, this simply led to an increasing need for imports of grain. Since the Mesta’s payments for these grazing rights went into the royal treasury, and a revocation of this practice would have enraged some of the crown’s strongest supporters, there was no prospect of amending the system. Finally, although there were some notable exceptions – the merchants involved in the wool trade, the financier Simon Ruiz, the region around Seville – the Castilian economy on the whole was also heavily dependent upon imports of foreign manufactures and upon the services provided by non-Spaniards, in particular Genoese, Portuguese, and Flemish entrepreneurs. It was dependent, too, upon the Dutch, even during hostilities; ‘by 1640 three-quarters of the goods in Spanish ports were delivered in Dutch ships’,50 to the profit of the nation’s greatest foes. Not surprisingly, Spain suffered from a constant trade imbalance, which could be made good only by the re-export of American gold and silver.

The horrendous costs of 140 years of war were, therefore, imposed upon a society which was economically ill-equipped to carry them. Unable to raise revenues by the most efficacious means, Habsburg monarchs resorted to a variety of expedients, easy in the short term but disastrous for the long-term good of the country. Taxes were steadily increased by all manner of means, but rarely fell upon the shoulders of those who could bear them most easily, and always tended to hurt commerce. Various privileges, monopolies, and honours were sold off by a government desperate for ready cash. A crude form of deficit financing was evolved, in part by borrowing heavily from the bankers on the credit of future Castilian taxes or American treasure, in part by selling interest-bearing government bonds (juros), which in turn drew in funds that might otherwise have been invested in trade and industry. But the government’s debt policy was always done in a hand-to-mouth fashion, without regard for prudent limitations and without the control which a central bank arguably might have imposed. Even by the later stages of Charles V’s reign, therefore, government revenues had been mortgaged for years in advance; in 1543, 65 per cent of ordinary revenue had to be spent paying interest on the juros already issued. The more the crown’s ‘ordinary’ income became alienated, the more desperate was its search for extraordinary revenues and new taxes. The silver coinage, for example, was repeatedly debased with copper vellon. On occasions, the government simply seized incoming American silver destined for private individuals and forced the latter to accept juros in compensation; on other occasions, as has been mentioned above, Spanish kings suspended interest repayments and declared themselves temporarily bankrupt. If this latter action did not always ruin the financial houses themselves, it certainly reduced Madrid’s credit rating for the future.

Even if some of the blows which buffeted the Castilian economy in these years were not man-made, their impact was the greater because of human folly. The plagues which depopulated much of the countryside around the beginning of the seventeenth century were unpredictable, but they added to the other causes – extortionate rents, the actions of the Mesta, military service – which were already hurting agriculture. The flow of American silver was bound to cause economic problems (especially price inflation) which no society of the time had the experience to handle, but the conditions prevailing in Spain meant that this phenomenon hurt the productive classes more than the unproductive, that the silver tended to flow swiftly out of Seville into the hands of foreign bankers and military provision merchants, and that these new transatlantic sources of wealth were exploited by the crown in a way which worked against rather than for the creation of ‘sound finance’. The flood of precious metals from the Indies, it was said, was to Spain as water on a roof – it poured on and then was drained away.

At the centre of the Spanish decline, therefore, was the failure to recognize the importance of preserving the economic underpinnings of a powerful military machine. Time and again the wrong measures were adopted. The expulsion of the Jews, and later the Moriscos; the closing of contacts with foreign universities; the government directive that the Biscayan shipyards should concentrate upon larger warships to the near exclusion of smaller, more useful trading vessels; the sale of monopolies which restricted trade; the heavy taxes upon wool exports, which made them uncompetitive in foreign markets; the internal customs barriers between the various Spanish kingdoms, which hurt commerce and drove up prices – these were just some of the ill-considered decisions which, in the long term, seriously affected Spain’s capacity to carry out the great military role which it had allocated to itself in European (and extra-European) affairs. Although the decline of Spanish power did not fully reveal itself until the 1640s, the causes had existed for decades beforehand.

International Comparisons

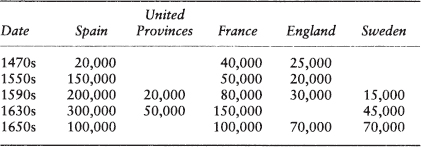

Yet this Habsburg failure, it is important to emphasize, was a relative one. To abandon the story here without examination of the experiences of the other European powers would leave an incomplete analysis. War, as one historian has argued, ‘was by far the severest test that faced the sixteenth-century state’.51 The changes in military techniques which permitted the great rise in the size of armies and the almost simultaneous evolution of large-scale naval conflict placed enormous new pressures upon the organized societies of the West. Each belligerent had to learn how to create a satisfactory administrative structure to meet the ‘military revolution’; and, of equal importance, it also had to devise new means of paying for the spiralling costs of war. The strains which were placed upon the Habsburg rulers and their subjects may, because of the sheer number of years in which their armies were fighting, have been unusual; but, as Table 1 shows, the challenge of supervising and financing bigger military forces was common to all states, many of which seemed to possess far fewer resources than did imperial Spain. How did they meet the test?

TABLE 1. Increase in Military Manpower, 1470–1660 52

Omitted from this brief survey is one of the most persistent and threatening foes of the Habsburgs, the Ottoman Empire, chiefly because its strengths and weaknesses were discussed in the previous chapter; but it is worth recalling that many of the problems and deficiencies with which Turkish administrators had to contend – strategical overextension, failure to tap resources efficiently, the crushing of commercial entrepreneurship in the cause of religious orthodoxy or military prestige – appear similar to those which troubled Philip II and his successors. Also omitted will be Russia and Prussia, as nations whose period as great powers in European politics had not yet arrived; and, further, Poland-Lithuania, which despite its territorial extent was too hampered by ethnic diversity and the fetters of feudalism (serfdom, a backward economy, an elective monarchy, ‘an aristocratic anarchy which was to make it a byword for political ineptitude’53) to commence its own takeoff to becoming a modern nation-state. Instead, the countries to be examined are the ‘new monarchies’ of France, England, and Sweden and the ‘bourgeois republic’ of the United Provinces.

Because France was the state which ultimately replaced Spain as the greatest military power, it has been natural for historians to focus upon the former’s many advantages. It would be wrong, however, to antedate the period of French predominance; throughout most of the years covered in this chapter, France looked – and was – decidedly weaker than its southern neighbour. In the few decades which followed the Hundred Years War, the consolidation of the crown’s territories vis-à-vis England, Burgundy, and Brittany, the habit of levying direct taxation (especially the taille, a poll tax), without application to the States General, the steady administrative work of the new secretaries of state, and the existence of a ‘royal’ army with a powerful artillery train made France appear to be a successful, unified, postfeudal monarchy.54 Yet the very fragility of this structure was soon to be made clear. The Italian wars, besides repeatedly showing how short-lived and disastrous were the French efforts to gain influence in that peninsula (even when allied with Venice or the Turks), were also very expensive: it was not only the Habsburgs but also the French crown which had to declare bankruptcy in the fateful year of 1557. Well before that crash, and despite all the increase in the taille and in indirect taxes like the gabelle and customs, the French monarchy was already resorting to heavy borrowings from financiers at high rates of interest (10–16 per cent), and to dubious expedients like selling offices. Worse still, it was in France rather than Spain or England that religious rivalries interacted with the ambitions of the great noble houses to produce a bloody and long-lasting civil war. Far from being a great force in international affairs, France after 1560 threatened to become the new cockpit of Europe, perhaps to be divided permanently along religious borders as was to be the fate of the Netherlands and Germany.55

Only after the accession of Henry of Navarre to the French throne as Henry IV (1589–1610), with his policies of internal compromise and external military actions against Spain, did matters improve; and the peace which he secured with Madrid in 1598 had the great advantage of maintaining France as an independent power. But it was a country severely weakened by civil war, brigandage, high prices, and interrupted trade and agriculture, and its fiscal system was in pieces. In 1596 the national debt was almost 300 million livres, and four-fifths of that year’s revenue of 31 million livres had already been assigned and alienated.56 For a long time thereafter, France was a recuperating society. Yet its natural resources were, comparatively, immense. Its population of around sixteen million inhabitants was twice that of Spain and four times that of England. While it may not have been as advanced as the Netherlands, northern Italy, and the London region in urbanization, commerce, and finance, its agriculture was diversified and healthy, and the country normally enjoyed a food surplus. The latent wealth of France was clearly demonstrated in the early seventeenth century, when Henry IV’s great minister Sully was supervising the economy and state finances. Apart from the paulette (which was the sale of, and tax on, hereditary offices), Sully introduced no new fiscal devices; what he did do was to overhaul the tax-collecting machinery, flush out thousands of individuals illegally claiming exemption, recover crown lands and income, and renegotiate the interest rates on the national debt. Within a few years after 1600, the state’s budget was in balance. In addition, Sully – anticipating Louis XIV’s minister, Colbert – tried to aid industry and agriculture by various means: reducing the taille, building bridges, roads, and canals to assist the transport of goods, encouraging cloth production, setting up royal factories to produce luxury wares which would replace imports, and so on. Not all of these measures worked to the extent hoped for, but the contrast with Philip III’s Spain was a marked one.57

It is difficult to say whether this work of recovery would have continued had not Henry IV been assassinated in 1610. What was clear was that none of the ‘new monarchies’ could properly function without adequate leadership, and between the time of Henry IV’s death and Richelieu’s consolidation of royal power in the 1630s, the internal politics of France, the disaffection of the Huguenots, and the nobility’s inclination toward intrigue once again weakened the country’s capacity to act as a European Great Power. Furthermore, when France eventually did engage openly in the Thirty Years War it was not, as some historians have tended to portray it, a unified, healthy power but a country still suffering from many of the old ailments. Aristocratic intrigue remained strong and was only to reach its peak in 1648–53; uprisings by the peasantry, by the unemployed urban workers, and by the Huguenots, together with the obstructionism of local officeholders, all interrupted the proper functioning of government; and the economy, affected by the general population decline, harsher climate, reduced agricultural output, and higher incidence of plagues which seems to have troubled much of Europe at this time,58 was hardly in a position to finance a great war.

From 1635 onward, therefore, French taxes had to be increased by a variety of means: the sale of offices was accelerated; and the taille, having been reduced in earlier years, was raised so much that the annual yield from it had doubled by 1643. But even this could not cover the costs of the struggle against the Habsburgs, both the direct military burden of supporting an army of 150,000 men and the subsidies to allies. In 1643, the year of the great French military victory over Spain at Rocroi, government expenditure was almost double its income and Mazarin, Richelieu’s successor, had been reduced to even more desperate sales of government offices and an even stricter control of the taille, both of which were highly unpopular. It was no coincidence that the rebellion of 1648 began with a tax strike against Mazarin’s new fiscal measures, and that such unrest swiftly led to a loss in the government’s credit and to its reluctant declaration of bankruptcy.59

Consequently, in the eleven years of Franco-Spanish warfare which remained after the general Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the two contestants resembled punch-drunk boxers, clinging to each other in a state of near-exhaustion to finish the other off. Each was suffering from domestic rebellion, widespread impoverishment, and dislike of the war, and was on the brink of financial collapse. It was true that, with generals like d’Enghien and Turenne and military reformers like Le Tellier, the French army was slowly emerging to be the greatest in Europe; but its naval power, built up by Richelieu, had swiftly disintegrated because of the demands of land warfare;60 and the country still needed a solid economic base. In the event, it was France’s good fortune that England, resurgent in its naval and military power under Cromwell, elected to join the conflict, thereby finally tilting the balance against a distressed Spain. The Treaty of the Pyrenees which followed was symbolic less of the greatness of France than of the relative decline of its overstretched southern neighbour, which had fought on with remarkable tenacity.61

In other words, each of the European powers possessed a mixture of strengths and weaknesses, and the real need was to prevent the latter from outweighing the former. This was certainly true of the ‘flank’ powers in the west and north, England and Sweden, whose interventions helped to check Habsburg ambitions on several critical occasions. It was hardly the case, for example, that England stood poised and well prepared for a continental conflict during these 140 years. The key to the English recovery following the Wars of the Roses had been Henry VII’s concentration upon domestic stability and financial prudence, at least after the peace with France in 1492. By cutting down on his own expenses, paying off his debts, and encouraging the wool trade, fishing, and commerce in general, the first Tudor monarch provided a much-needed breathing space for a country hit by civil war and unrest; the natural productivity of agriculture, the flourishing cloth trade to the Low Countries, the increasing use of the rich offshore fishing grounds, and the general bustle of coastal trade did the rest. In the area of national finances, the king’s recovery of crown lands and seizure of those belonging to rebels and rival contenders to the throne, the customs yield from growing trade, and the profits from the Star Chamber and other courts all combined to produce a healthy balance.62

But political and fiscal stability did not necessarily equal power. Compared with the far greater populations of France and Spain, the three to four million inhabitants of England and Wales did not seem much. The country’s financial institutions and commercial infrastructures were crude, compared with those in Italy, southern Germany, and the Low Countries, although considerable industrial growth was to occur in the course of the ‘Tudor century’.63 At the military level, the gap was much wider. Once he was secure upon the throne, Henry VII had dissolved much of his own army and forbade (with a few exceptions) the private armies of the great magnates; apart from the ‘Yeomen of the Guard’ and certain garrison troops, there was no regular standing army in England during this period when Franco-Habsburg wars in Italy were changing the nature and dimensions of military conflict. Consequently, such forces as did exist under the early Tudors were still equipped with traditional weapons (longbow, bill) and raised in the traditional way (county militia, volunteer ‘companies’, and so on). However, this backwardness did not keep his successor, Henry VIII, from campaigning against the Scots or even deter his interventions of 1513 and 1522–3 against France, since the English king could hire large numbers of ‘modern’ troops – pikemen, arquebusiers, heavy cavalry – from Germany.64

If neither these early English operations in France nor the two later invasions in 1528 and 1544 ended in military disaster – if, indeed, they often forced the French monarch to buy off the troublesome English raiders – they certainly had devastating financial consequences. Of the total expenditures of £700,000 by the Treasury of the Chamber in 1513, for example, £632,000 was allocated toward soldiers’ pay, ordnance, warships, and other military outgoings.* Soon, Henry VII’s accumulated reserves were all spent by his ambitious heir, and Henry VIII’s chief minister, Wolsey, was provoking widespread complaints by his efforts to gain money from forced loans, ‘benevolences’, and other arbitrary means. Only with Thomas Cromwell’s assault upon church lands in the 1530s was the financial position eased; in fact, the English Reformation doubled the royal revenues and permitted large-scale spending upon defensive military projects – fortresses along the Channel coast and Scottish border, new and powerful warships for the Royal Navy, the suppression of rebellions in Ireland. But the disastrous wars against France and Scotland in the 1540s cost an enormous £2,135,000, which was about ten times the normal income of the crown. This forced the king’s ministers into the most desperate of expedients: the sale of religious properties at low rates, the seizure of the estates of nobles on trumped-up charges, repeated forced loans, the great debasement of the coinage, and finally the recourse to the Fuggers and other foreign bankers.65 Settling England’s differences with France in 1550 was thus a welcome relief to a near-bankrupt government.

What this all indicated, therefore, was the very real limits upon England’s power in the first half of the sixteenth century. It was a centralized and relatively homogeneous state, although much less so in the border areas and in Ireland, which could always distract royal resources and attention. Thanks chiefly to the interest of Henry VIII, it was defensively strong, with some modern forts, artillery, dockyards, a considerable armaments industry, and a well-equipped navy. But it was militarily backward in the quality of its army, and its finances could not fund a large-scale war. When Elizabeth I became monarch in 1558, she was prudent enough to recognize these limitations and to achieve her ends without breaching them. In the dangerous post-1570 years, when the Counter-Reformation was at its height and Spanish troops were active in the Netherlands, this was a difficult task to fulfil. Since her country was no match for any of the real ‘superpowers’ of Europe, Elizabeth sought to maintain England’s independence by diplomacy and, even when Anglo-Spanish relations worsened, to allow the ‘cold war’ against Philip II to be conducted at sea, which was at least economical and occasionally profitable.66 Although needing to provide monies to secure her Scottish and Irish flanks and to give aid to the Dutch rebels in the late 1570s, Elizabeth and her ministers succeeded in building up a healthy surplus during the first twenty-five years of her reign – which was just as well, since the queen sorely needed a ‘war chest’ once the decision was taken in 1585 to dispatch an expeditionary force under Leicester to the Netherlands.