Полная версия

The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

… if a nation be so situated that it is neither forced to defend itself by land nor induced to seek extension of its territory by way of land, it has, by the very unity of its aim directed upon the sea, an advantage as compared with a people one of whose boundaries is continental.35

Mahan’s statement presumes, of course, a number of further points. The first is that the British government would not have distractions on its flanks – which after the conquest of Ireland and the Act of Union with Scotland (1707), was essentially correct, though it is interesting to note those occasional later French attempts to embarrass Britain along the Celtic fringes, something which London took very seriously indeed. An Irish uprising was much closer to home than the strategical embarrassment offered by the American rebels. Fortunately for the British, this vulnerability was never properly exploited by foes.

The second assumption in Mahan’s statement is the superior status of sea warfare and of sea power over their equivalents on land. This was a deeply held belief of what has been termed the ‘navalist’ school of strategy,36 and seemed well justified by post-1500 economic and political trends. The steady shift in the main trade routes from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic and the great profits which could be made from colonial and commercial ventures in the West Indies, North America, the Indian subcontinent, and the Far East naturally benefited a country situated off the western flank of the European continent. To be sure, it also required a government aware of the importance of maritime trade and ready to pay for a large war fleet. Subject to that precondition, the British political elite seemed by the eighteenth century to have discovered a happy recipe for the continuous growth of national wealth and power. Flourishing overseas trade aided the British economy, encouraged seamanship and shipbuilding, provided funds for the national Exchequer, and was the lifeline to the colonies. The colonies not only offered outlets for British products but also supplied many raw materials, from the valuable sugar, tobacco, and calicoes to the increasingly important North American naval stores. And the Royal Navy ensured respect for British merchants in times of peace and protected their trade and garnered further colonial territories in war, to the country’s political and economic benefit. Trade, colonies, and the navy thus formed a ‘virtuous triangle’, reciprocally interacting to Britain’s long-term advantage.

While this explanation of Britain’s rise was partly valid, it was not the whole truth. Like so many mercantilist works, Mahan’s tended to emphasize the importance of Britain’s external commerce as opposed to domestic production, and in particular to exaggerate the importance of the ‘colonial’ trades. Agriculture remained the fundament of British wealth throughout the eighteenth century, and exports (whose ratio to total national income was probably less than 10 per cent until the 1780s) were often subject to strong foreign competition and to tariffs, for which no amount of naval power could compensate.37 The navalist viewpoint also inclined to forget the further fact that British trade with the Baltic, Germany, and the Mediterranean lands was – although growing less swiftly than those in sugar, spices, and slaves – still of great economic importance;* so that a France permanently dominant in Europe might, as the events of 1806–12 showed, be able to deliver a dreadful blow to British manufacturing industry. Under such circumstances, isolationism from European power politics could be economic folly.

There was also a critically important ‘continental’ dimension to British grand strategy, overlooked by those whose gaze was turned outward to the West Indies, Canada, and India. Fighting a purely maritime war was perfectly logical during the Anglo-Dutch struggles of 1652–4, 1665–7, and 1672–4, since commercial rivalry between the two sea powers was at the root of that antagonism. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, however, when William of Orange secured the English throne, the strategical situation was quite transformed. The challenge to British interests during the seven wars which were to occur between 1689 and 1815 was posed by an essentially land-based power, France. True, the French would take this fight to the western hemisphere, to the Indian Ocean, to Egypt, and elsewhere; but those campaigns, although important to London and Liverpool traders, never posed a direct threat to British national security. The latter would arise only with the prospect of French military victories over the Dutch, the Hanoverians, and the Prussians, thereby leaving France supreme in west-central Europe long enough to amass shipbuilding resources capable of eroding British naval mastery. It was therefore not merely William III’s personal union with the United Provinces, or the later Hanoverian ties, which caused successive British governments to intervene militarily on the continent of Europe in these decades. There was also the compelling argument – echoing Elizabeth I’s fears about Spain – that France’s enemies had to be given assistance inside Europe, to contain Bourbon (and Napoleonic) ambitions and thus to preserve Britain’s own long-term interests. A ‘maritime’ and a ‘continental’ strategy were, according to this viewpoint, complementary rather than antagonistic.

The essence of this strategic calculation was nicely expressed by the Duke of Newcastle in 1742:

France will outdo us at sea when they have nothing to fear on land. I have always maintained that our marine should protect our alliances on the Continent, and so, by diverting the expense of France, enable us to maintain our superiority at sea.38

This British support to countries willing to ‘divert the expense of France’ came in two chief forms. The first was direct military operations, either by peripheral raids to distract the French army or by the dispatch of a more substantial expeditionary force to fight alongside whatever allies Britain might possess at the time. The raiding strategy seemed cheaper and was much beloved by certain ministers, but it usually had negligible effects and occasionally ended in disaster (like the expedition to Walcheren of 1809). The provision of a continental army was more expensive in terms of men and money, but, as the campaigns of Marlborough and Wellington demonstrated, was also much more likely to assist in the preservation of the European balance.

The second form of British aid was financial, whether by directly buying Hessian and other mercenaries to fight against France, or by giving subsidies to the allies. Frederick the Great, for example, received from the British the substantial sum of £675,000 each year from 1757 to 1760; and in the closing stages of the Napoleonic War the flow of British funds reached far greater proportions (e.g. £11 million to various allies in 1813 alone, and £65 million for the war as a whole). But all this had been possible only because the expansion of British trade and commerce, particularly in the lucrative overseas markets, allowed the government to raise loans and taxes of unprecedented amounts without suffering national bankruptcy. Thus, while diverting ‘the expense of France’ inside Europe was a costly business, it usually ensured that the French could neither mount a sustained campaign against maritime trade nor so dominate the European continent that they would be free to threaten an invasion of the home islands – which in turn permitted London to finance its wars and to subsidize its allies. Geographical advantage and economic benefit were thus merged to enable the British brilliantly to pursue a Janus-faced strategy: ‘with one face turned towards the Continent to trim the balance of power and the other directed at sea to strengthen her maritime dominance’.39

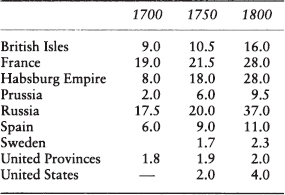

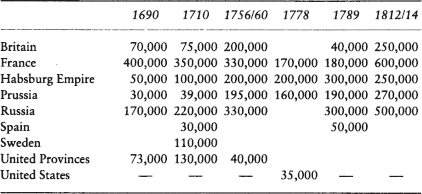

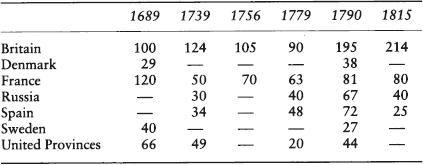

Only after one grasps the importance of the financial and geographical factors described above can one make full sense of the statistics of the growing populations and military/naval strengths of the powers in this period (see Tables 3–5).

As readers familiar with statistics will be aware, such crude figures have to be treated with extreme care. Population totals, especially in the early period, are merely guesses (and in Russia’s case the margin for error could be several millions). Army sizes fluctuated widely, depending upon whether the date chosen is at the outset, the midpoint, or the culmination of a particular war; and the total figures often include substantial mercenary units and (in Napoleon’s case) even the troops of reluctantly co-opted allies. The number of ships of the line indicated neither their readiness for battle nor, necessarily, the availability of trained crews to man them. Moreover, statistics take no account of generalship or seamanship, of competence or neglect, of national fervour or faintheartedness. Even so, it might appear that the above figures at least roughly reflect the chief power-political trends of the age: France and, increasingly, Russia lead in population and military terms; Britain is usually unchallenged at sea; Prussia overtakes Spain, Sweden, and the United Provinces; and France comes closer to dominating Europe with the enormous armies of Louis XIV and Napoleon than at any time in the intervening century.

TABLE 3. Populations of the Powers, 1700–1800 40

(millions)

TABLE 4. Size of Armies, 1690–1814 41

(men)

TABLE 5. Size of Navies, 1689–1815 42

(ships of the line)

Aware of the financial and geographical dimensions of these 150 years of Great Power struggles, however, one can see that further refinements have to be made to the picture suggested in these three tables. For example, the swift decline of the United Provinces relative to other nations in respect to army size was not repeated in the area of war finance, where its role was crucial for a very long while. The nonmilitary character of the United States conceals the fact that it could pose a considerable strategical distraction. The figures also understate the military contribution of Britain, since it might be subsidizing 100,000 allied troops (in 1813, 450,000!) as well as providing for its own army, and naval personnel of 140,000 in 1813–14;43 conversely, the true strength of Prussia and the Habsburg Empire, dependent on subsidies during most wars, would be exaggerated if one merely considered the size of their armies. As noted above, the enormous military establishments of France were rendered less effective through financial weaknesses and geostrategical obstacles, while those of Russia were eroded by economic backwardness and sheer distance. The strengths and weaknesses of each of these powers ought to be borne in mind as we turn to a more detailed examination of the wars themselves.

The Winning of Wars, 1660–1763

When Louis XIV took over full direction of the French government in March 1661, the European scene was particularly favourable to a monarch determined to impose his views upon it.44 To the south, Spain was still exhausting itself in the futile attempt to recover Portugal. Across the Channel, a restored monarchy under Charles II was trying to find its feet, and in English commercial circles great jealousy of the Dutch existed. In the north, a recent war had left both Denmark and Sweden weakened. In Germany, the Protestant princes watched suspiciously for any fresh Habsburg attempt to improve its position, but the imperial government in Vienna had problems enough in Hungary and Transylvania, and slightly later with a revival of Ottoman power. Poland was already wilting under the effort of fending off Swedish and Muscovite predators. Thus French diplomacy, in the best traditions of Richelieu, could easily take advantage of these circumstances, playing off the Portuguese against Spain, the Magyars, Turks, and German princes against Austria, and the English against the Dutch – while buttressing France’s own geographical (and army-recruitment) position by its important 1663 treaty with the Swiss cantons. All this gave Louis XIV time enough to establish himself as absolute monarch, secure from the internal challenges which had afflicted French governments during the preceding century. More important still, it gave Colbert, Le Tellier, and the other key ministers the chance to overhaul the administration and to lavish resources upon the army and the navy in anticipation of the Sun King’s pursuit of glory.45

It was therefore all too easy for Louis to try to ‘round off’ the borders of France in the early stages of his reign, the more especially since Anglo-Dutch relations had deteriorated into open hostilities by 1665 (the Second Anglo-Dutch War). Although France was pledged to support the United Provinces, it actually played little part in the campaigns at sea and instead prepared itself for an invasion of the southern Netherlands, which were still owned by a weakened Spain. When the French finally launched their invasion, in May 1667, town after town quickly fell into their hands. What then followed was an early example of the rapid diplomatic shifts of this period. The English and the Dutch, wearying of their mutually unprofitable war and fearing French ambitions, made peace at Breda in July and, joined by Sweden, sought to ‘mediate’ in the Franco-Spanish dispute in order to limit Louis’s gains. The 1668 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle achieved just that, but at the cost of infuriating the French king, who eventually made up his mind to be revenged upon the United Provinces, which he perceived to be the chief obstacle to his ambitions. For the next few years, while Colbert waged his tariff war against the Dutch, the French army and navy were further built up. Secret diplomacy seduced England and Sweden from their alliance with the United Provinces and quieted the fears of the Austrians and the German states. By 1672 the French war machine, aided by the English at sea, was ready to strike.

Although it was London which first declared war upon the United Provinces, the dismal English effort in the third Anglo-Dutch conflict of 1672–4 requires minimal space here. Checked by the brilliant efforts of de Ruyter at sea, and therefore unable to achieve anything on land, Charles II’s government came under increasing domestic criticism: evidence of political duplicity and financial mismanagement, and a strong dislike of being allied to an autocratic, Catholic power like France, made the war unpopular and forced the government to pull out of it by 1674. In retrospect, it is a reminder of how immature and uncertain the political, financial, and administrative bases of English power still were under the later Stuarts.46 London’s change of policy was of international importance, however, in that it partly reflected the widespread alarm which Louis XIV’s designs were now arousing throughout Europe. Within another year, Dutch diplomacy and subsidies found many allies willing to throw their weight against the French. German principalities, Brandenburg (which defeated France’s only remaining partner, Sweden, at Fehrbellin in 1675), Denmark, Spain, and the Habsburg Empire all entered the issue. It was not that this coalition of states was strong enough to overwhelm France; most of them had smallish armies, and distractions on their own flanks; and the core of the anti-French alliance remained the United Provinces under their new leader, William of Orange. But the watery barrier in the north and the vulnerability of the French army’s lines against various foes in the Rhineland meant that Louis himself could make no dramatic gains. A similar sort of stalemate existed at sea; the French navy controlled the Mediterranean, Dutch and Danish fleets held the Baltic, and neither side could prevail in the West Indies. Both French and Dutch commerce were badly affected in this war, to the indirect benefit of neutrals like the British. By 1678, in fact, the Amsterdam merchant classes had pushed their own government into a separate peace with France, which in turn meant that the German states (reliant upon Dutch subsidies) could not continue to fight on their own.

Although the Nymegen peace treaties of 1678–9 brought the open fighting to an end, Louis XIV’s evident desire to round off France’s northern borders, his claim to be ‘the arbiter of Europe’, and the alarming fact that he was maintaining an army of 200,000 troops in peacetime disquieted Germans, Dutchmen, Spaniards, and Englishmen alike.47 This did not mean an immediate return to war. The Dutch merchants preferred to trade in peace; the German princes, like Charles II of England, were tied to Paris by subsidies; and the Habsburg Empire was engaged in a desperate struggle with the Turks. When Spain endeavoured to protect its Luxembourg territories from France in 1683, therefore, it had to fight alone and suffer inevitable defeat.

From 1685, however, things began to swing against France. The persecution of the Huguenots shocked Protestant Europe. Within another two years, the Turks had been soundly defeated and driven away from Vienna; and the Emperor Leopold, with enhanced prestige and military strength, could at last turn some of his attention to the west. By September 1688, a now-nervous French king decided to invade Germany, finally turning this European ‘cold’ war into a hot one. Not only did France’s action provoke its continental rivals into declaring hostilities, it also gave William of Orange the opportunity to slip across the Channel and replace the discredited James II on the English throne.

By the end of 1689, therefore, France stood alone against the United Provinces, England, the Habsburg Empire, Spain, Savoy, and the major German states.48 This was not as alarming a combination as it seemed, and the ‘hard core’ of the Grand Alliance really consisted of the Anglo-Dutch forces and the German states. Although a disparate grouping in certain respects, they possessed sufficient determination, financial resources, armies, and fleets to balance the Sun King’s France. Ten years earlier, Louis might possibly have prevailed, but French finances and trade were now much less satisfactory after Colbert’s death, and neither the army nor the navy – although numerically daunting – was equipped for sustained and distant fighting. A swift defeat of one of the major allies could break the deadlock, but where should that thrust be directed, and had Louis the will to order bold measures? For three years he dithered; and when in 1692 he finally assembled an invasion force of 24,000 troops to dispatch across the Channel, the ‘maritime powers’ were simply too strong, smashing up the French warships and barges at Barfleur-La Hogue.49

From 1692 onward, the conflict at sea became a slow, grinding, mutually ruinous war against trade. Adopting a commerce-raiding strategy, the French government encouraged its privateers to prey upon Anglo-Dutch shipping while it reduced its own allocations to the battle fleet. The allied navies, for their part, endeavoured to increase the pressures on the French economy by instituting a commercial blockade, thus abandoning the Dutch habit of trading with the enemy. Neither measure brought the opponent to his knees; each increased the economic burdens of the war, making it unpopular with merchants as well as peasants, who were already suffering from a succession of poor harvests. The land campaigns were also expensive, slow struggles against fortresses and across waterways: Vauban’s fortifications made France virtually impregnable, but the same sort of obstacles prevented an easy French advance into Holland or the Palatinate. With each side maintaining over 250,000 men in the field, the costs were horrendous, even to these rich countries.50 While there were also extra-European campaigns (West Indies, Newfoundland, Acadia, Pondicherry), none was of sufficient importance to swing the basic continental or maritime balance. Thus by 1696, with Tory squires and Amsterdam burghers complaining about excessive taxes, and with France afflicted by famine, both William and Louis had cause enough to compromise.

In consequence, the Treaty of Ryswick (1697), while allowing Louis some of his earlier border gains, saw a general return to the prewar status quo. Nonetheless, the results of the Nine Years War of 1689–97 were not as insignificant as contemporary critics alleged. French ambitions had certainly been blunted on land, and its naval power eroded at sea. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 had been upheld, and England had secured its Irish flank, strengthened its financial institutions, and rebuilt its army and navy. And an Anglo-Dutch-German tradition of keeping France out of Flanders and the Rhineland was established. Albeit at great cost, the political plurality of Europe had been reasserted.

Given the war-weary mood in most capitals, a renewal of the conflict scarcely seemed possible. However, when Louis’s grandson was offered the succession to the Spanish throne in 1700, the Sun King saw in this an ideal opportunity to enhance France’s power. Instead of compromising with his potential rivals, he swiftly occupied the southern Netherlands on his grandson’s behalf, and also secured exclusive commercial concessions for French traders in Spain’s large empire in the western hemisphere. By these and various other provocations, he alarmed the British and Dutch sufficiently to cause them to join Austria in 1701 in another coalition struggle to check Louis’s ambitions: the War of the Spanish Succession.

Once again, the general balance of forces and taxable resources suggested that each alliance could seriously hurt, but not overwhelm, the other.51 In some respects, Louis was in a stronger position than in the 1689–97 war. The Spaniards readily took to his grandson, now their Philip V, and the ‘Bourbon powers’ could work together in many theatres; French finances certainly benefited from the import of Spanish silver. Moreover, France had been geared up militarily – to the level, at one period, of supporting nearly half a million troops. However, the Austrians, less troubled on their Balkan flank, were playing a greater role in this war than they had in the previous one. Most important of all, a determined British government was to commit its considerable national resources, in the form of hefty subsidies to German allies, an overpowering fleet, and, unusually, a large-scale continental army under the brilliant Marlborough. The latter, with between 40,000 and 70,000 British and mercenary troops, could join an excellent Dutch army of over 100,000 men and a Habsburg army of a similar size to frustrate Louis’s attempt to impose his wishes upon Europe.

This did not mean, however, that the Grand Alliance could impose its wishes upon France, or, for that matter, upon Spain. Outside those two kingdoms, it is true, events turned steadily in favour of the allies. Marlborough’s decisive victory at Blenheim (1704) severely hurt the Franco-Bavarian armies and freed Austria from a French invasion threat. The later battle of Ramillies (1706) gave the Anglo-Dutch forces most of the southern Netherlands, and that at Oudenarde (1708) brutally stopped the French effort to regain ground there.52

At sea, with no enemy main fleet to deal with after the inconclusive battle of Málaga (1704), the Royal Navy and its declining Dutch equivalent could demonstrate the flexibility of superior naval power. The new ally, Portugal, could be sustained from the sea, while Lisbon in turn provided a forward fleet base and Brazil a source of gold. Troops could be dispatched to the western hemisphere to attack French possessions in the West Indies and North America, and raiding squadrons could hunt for Spanish bullion fleets. The seizure of Gibraltar not only gave the Royal Navy a base controlling the exit from that sea, but divided the Franco-Spanish bases – and fleets. British fleets ensured the capture of Minorca and Sardinia; they covered Savoy and the Italian coasts from French attack; and when the allies went on to the offensive, they shepherded and supplied the imperial armies’ invasion of Spain and supported the assault upon Toulon.53