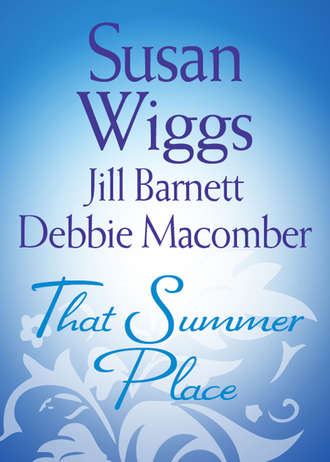

Полная версия

That Summer Place: Island Time / Old Things / Private Paradise

A few minutes later, the wind had picked up and the rain was coming down so hard it bounced back up from the ground. Over five times Catherine had read and followed the old instructions that were engraved on a metal plate attached to the lid, and still nothing happened.

“Who writes these things?” she muttered. “Probably the same people who write software manuals.”

She took the flashlight from Dana and banged the generator a good one.

The motor gave a half-hearted start, then suddenly died.

“Oh Mom! It almost started!” Dana reached for the flashlight. “Let me try.” She hit it a few times.

The generator started up with a loud coughing rev like a huge lawnmower.

She and the girls cheered, then she took the flashlight from Dana and turned to trudge back to the porch. The clouds slipped by steadily and the moon cracked through with bright silver light. The wind blew in sudden, whipping gusts and caught the umbrella; it slipped from Aly’s hands and tumbled across the yard like an shiny wet acrobat.

They chased after it, all of them yelling “I’ll get it! I’ll get it!” Dana made a grab for it at the same time as Aly. Both girls fell in the mud just as the umbrella danced away from their outstretched hands.

Catherine looked down at her muddy children and began to laugh. “First one to get the umbrella doesn’t have to do any dishes for a week!” She ran after the umbrella while her girls scrambled after her.

“You’re cheating, Mom! You had a head start!”

“That’s because I’m old!” she shouted over her shoulder as she ran in front of them.

It became a game, one of them reaching for the umbrella just as the wind snatched it away, leaving behind nothing but their laughter. They were so wet the umbrella wouldn’t have done them a bit of good, but it didn’t matter. Between the stubborn and wild Winslow women, one of them was going to get that blasted umbrella.

Soaking wet and shouting, Catherine was now the closest to it. She gave a triumphant holler and launched after it like a missile.

One moment she was standing, the next she slipped in the mud and skidded on her stomach across the wet grass, all to the sound of her daughters’ laughter being carried upward by that rascally wind.

Mud splashed up into her face and through her wet hair, but she didn’t care. She hadn’t had this much fun since she was ten and her dad had brought home a bright yellow Slip ‘n Slide he’d attached to the garden hose in the yard.

“Yahoo! I’ve got it!” She laughed and hooted, then scrambled up and chased the umbrella, until she realized she couldn’t run fast enough to catch it. So she dove toward the wet ground on purpose and just slid after it on her belly.

Right into a large pair of Wellington boots.

A man’s Wellington boots.

For a second she stared at the huge rubber tips, partially sunken in the new mud, then slowly raised her wet head to look up.

The moonlight was behind him and all she could see was a tall silhouette of a man holding the umbrella. He shined a flashlight in her face and held it there.

She squinted and held up her hand to block out the glare.

Without a word he turned the light away from her.

She stared up at him.

His features were blurred, so she swiped the mud and water from her face and slapped her wet hair out of her eyes. Just for good measure she pulled the flashlight out of her jacket and shone it upward, figuring she could either blind him or beat him with it if he meant them any harm.

The light shone on his face. Everything seemed to stop suddenly. The rain. The wind. Her heart. Her breath.

The whole world stopped.

She stared up at him and felt as if she were stepping into her most secret dreams. She whispered, “Michael?”

Seven

It took Michael a minute to realize just who he was looking at. Every emotion imaginable raced through him. Yet he didn’t react; he had spent too much time in Vietnam, where he’d learned to never be surprised, and had developed nerves of steel that served him in his business and his personal life.

Until this very moment.

This was a face he had seen only in his memory for the last thirty years.

She was covered in mud and soaking wet. Her hair was dark and stringy from the rain, her mouth open in stunned surprise.

But that face was still uniquely Catherine.

“Hi, Squirt.”

“Ohmygod…It is you.” She buried her head in her arms the way she had when she was eleven. It was as if she still thought her embarrassing moments would just go away if she didn’t look at him.

“How long have you been standing there?” she said into her arms.

“Long enough to be entertained.”

She took a deep breath. “That’s what I was afraid of.”

“Who are you?” A young girl stuck her wet and muddy face in front of him. It was almost exactly the same face he had seen hanging upside-down from a tree.

Michael felt as if he were in an episode of “Star Trek,” thrown back to a unique and significant time in his life just to teach him something.

The youngest girl looked exactly like Catherine did at eleven. Another Squirt.

For one brief moment—just a nanosecond of regret that had never hit him before—he was sorry he had never fathered a child.

While he stood there speechless and frozen in time, Catherine rolled over and sat up, resting her hands on her bent knees. She looked at the two girls. “This is Michael Packard, girls. An old friend.”

“There are no houses around here,” the older girl said after scanning the trees. She looked at him as if she expected him to grow horns. “Where’d you come from?”

He didn’t take his eyes off Catherine when he answered her. “The stork dropped me down the chimney.”

Catherine looked right into his eyes, half surprised and half amused. A moment later she began to laugh.

He could see she remembered that all those years ago he’d said those same words to her. A second later the older girl called him a weirdo under her breath, and Michael decided that time didn’t change people very much.

“He was teasing you, Dana,” Catherine said.

He stuck out a hand to help her up. “Here.”

She sat there for a second, her gaze wandering over him. She paused to look at the tool belt hanging on his hips. He wondered what she was thinking when she looked at him like that.

She looked down quickly as if to hide her thoughts, like she was embarrassed. She wiped her muddy hand off on her even muddier pants, then put it into his hand.

He started to pull her to her feet.

“Michael is the handyman on the island,” she told her daughters.

He had the sudden urge to drop her.

“Just like his grandfather was,” she added not looking at him and in a tone that was all too bright and cheery to be real.

Damn it if he didn’t just let go.

She plopped back down in the mud with a splat, and her daughters laughed.

“Sorry,” he said through a slightly tight jaw.

She looked up at him with a stunned expression.

He shrugged. “My hand slipped.” He stuck out his hand again.

“No, thanks. I can get up on my own.” She stood then with her back to him so he couldn’t see her face.

She thought he was a handyman. And from her voice he could tell she was disappointed.

He shouldn’t have let go of her. It was vindictive.

He looked away quickly because he thought he might smile. He took a deep breath, shoved his hands into his pockets, and with a straight face he turned back around.

The older girl was looking at him suspiciously. He waited a moment, then gave her the same speculative look she was giving him.

She stared at him longer than most. He wasn’t certain how to gauge that—as teenaged stubbornness or an innate strength of character he should respect.

She finally looked down and began to fiddle with her hand.

“These are my daughters. Dana and Aly.”

He nodded to them. Daughters meant there was a father. A husband. He glanced at her hand. No ring.

The rain changed meter and began to pound down in sheets. They all looked up for a second, then Catherine touched his shoulder. “Come on to the house!”

She half-ran, half-trudged toward the house with the girls running ahead of her.

At the crooked porch, she pried off her wet tennis shoes by stepping on her heel with one foot, then did the same with the other foot. Her daughters pulled off their shoes and rushed inside, while he sat on an old bench and pulled off his mud boots.

Catherine waited for him, watching him until he stood and she had to look up. She opened the old screen door, which creaked on its hinges the way it used to.

“Come on in,” she said in a rushed voice that was breathy and still too sexy for her own good.

He felt a little numb as he followed her inside and stood there while she took his wet jacket and hung it on a hook. They went into the big old living room where a red and yellow glow from an old lava lamp made the room seem warmer.

No husband on the sofa. No man’s jacket on the hook or boots on the porch. No man.

She walked a few feet into the room and stopped so suddenly it was as if she had hit an invisible wall.

He followed her gaze to the sofa where empty soda cans and boxes and ice cream cartons littered the sofa and floor. A low table was covered with a jigsaw puzzle.

She mumbled something that sounded like a swear word, then rushed over and began to scoop together the mess.

“Girls, help me here.” She jammed soda cans under her arms and he tried not to laugh.

“Don’t mess up the puzzle, Mom,” the youngest girl said as she bent down and picked up a spoon that had fallen on the rug next to a big gray cat that was sound asleep.

From the way Catherine darted all over the place snatching up empty food containers, he could see she was embarrassed.

Both girls stood there in front of him, soaking wet and staring at him as if they expected him to do something strange, like split and multiply.

He should just leave. Take his tool belt and go back to his cabin and forget Catherine was ever here.

Instead he squatted down and gave the cat a stroke on his back. “Hey, fella.”

“He likes you.”

Michael looked up at the kid called Aly and nodded. “You sound surprised.”

“He doesn’t usually let strangers touch him. His name is Harold.”

Harold rolled over on his side and began to purr loudly.

“What would you like to drink?” Catherine called out from the kitchen where she was stuffing trash into a bag under the sink. “I don’t have beer, but I have soft drinks and plenty of coffee.”

Michael sat down on the sofa and flinched. He reached behind him and pulled out an empty aluminum can.

Cream soda.

The youngest girl giggled and took it from him. He gave her a quick wink and said to Catherine, “Coffee’s fine.”

Catherine looked at her daughters and said, “Go upstairs and change out of those wet clothes, girls. I’m not sure which one of you is the muddiest.”

Dana gave him a look as if she were weighing whether he could be trusted to be left alone with her mom.

Aly jabbed her with an elbow. “Come on.”

They went upstairs together arguing over who looked the worst.

At the top of the landing Aly stuck her head out over the stair rail and looked down just as Catherine came out of the kitchen with a tray.

“We’re both wrong, Dana.”

Catherine stopped in front of the coffee table and looked up at her daughter, who was grinning down at her.

“Mother’s the muddiest!” she said, then disappeared after her sister.

He watched Catherine’s face as she looked down at herself for the first time. He could read her expression perfectly.

Again his first thought was that he should be a gentleman and leave. Instead he stood and took the tray from her. “Go get into some dry clothes.”

She nodded and muddy hair fell into her face and stuck to her lips. She looked at him rather helplessly, then raised her chin as if she wasn’t soaked and covered in mud and she walked toward the back bedroom.

Catherine Wardwell and her stubborn pride; it was still there after all these years.

He watched her, because she was Catherine and because he didn’t want to look away, even though he knew it would make her feel less conspicuous.

Just before she turned the corner of the hall, she flicked on the hall light and he caught the expression on her pale face. She looked like she wanted the ground to just open up and swallow her.

Catherine certainly had wanted the earth to open up and swallow her. The trouble was, she looked as if it already had and then spit her back out again.

She stood at the mirror in the bathroom and had trouble looking at herself without wincing. It was worse than she had imagined.

There was grass in her hair, which was glued to her head and plastered around her forehead and ears. Flecks of mud and slim green blades of grass were stuck to her cheeks and neck. Her sweatshirt was soaked and clung to her chest.

She stepped back and turned around. The muddy sweatpants were stuck to her butt, too. She continued to stare. Oh, why had she quit step-aerobics?

Shoot, shoot, shoot, shoot!

She shoved back the shower curtain, turned on the shower and stripped off her clothes, then hopped inside. She soaped up, washed her hair and was out in about two minutes. She dried off, shrugged into a robe, brushed her teeth longer than necessary, then went into the bedroom.

She changed clothes seven times in under five minutes, until she finally decided her bra was the problem and put on a different one, then hiked the adjustment on the straps up a good inch. After that her green cotton sweater looked better.

She hopped around the room, shoving her legs into the pair of jeans that made them look the longest, then she laid down on the bed so she could zip them up.

She stood and jerked the sweater down over her butt and ran back to the bathroom, where she swiped on some deodorant, brushed her wet hair back and twisted it up, then stuck in a hair pick to hold it.

She slapped on some makeup. She didn’t need any blush; her face was too flushed already. She was nervous, so she put on more deodorant, then stood back and looked at herself.

He had been attracted to her once, when they were young. But what would he see when he looked at her now?

When she looked at herself she saw her outside changing, growing older, while inside she still felt young. Aging was a strange thing—made you feel like you were wearing a striped shirt and plaid pants. Mismatched. Because you never felt as old inside as you looked on the outside.

There were those days now when she went to put on her eye shadow and little lines of it caked at the corners of her eyes. She had to smudge the eye shadow into her skin with a Q-tip.

And there were those little vertical lines along her lips that her old lipstick had recently started bleeding into. She’d had to change types of lip liner and lipstick, something matte that wouldn’t seep in the age cracks that were just beginning to show on her lips.

She put one finger at each end of her mouth and pulled her lips back. Collagen? A peel?

Neither appealed to her.

Bad pun.

She stood there for a long time, gripping the sides of the sink with her hands, hesitant to go out of the bathroom. Scared. Deep down inside, she wanted to still be young for him.

She stared at herself in the mirror. A moment later she pulled her bra straps out of the neckline of her sweater and tightened them another half an inch, then she bent over and grabbed the bottom of her bra and wiggled so she filled the cups differently. Higher. Younger?

She looked at the result in the mirror, then tugged down on her sweater. That was better. She wished she had packed perfume. She lifted her arm. She smelled like Camay soap and baby powder-scented deodorant.

Better than smelling like a garden slug.

Her hand closed over the glass door knob. She took a deep breath and finally mustered the courage to leave the bathroom.

Eight

Michael knew the exact moment she stepped into the room. It should have frightened him that he could be so attuned to another person that her mere presence could distract him. With anyone else he would have fought that awareness with a vengeance. Because it was a control thing, and he was a man who needed to be in control.

His awareness of Catherine was different; it didn’t threaten him. It somehow felt right, as if the power between them, this thread of something that linked them together, was an innate part of him.

He glanced up at her from over the rim of a coffee mug. She stood framed in the hall doorway as if she were a painting that had just come alive.

She had been a knockout when she was a young woman. Fresh and tall and sleek. Now she was thirty years older, still beautiful, but added to her face was something better than youthful beauty.

She had character.

He had lived long enough to understand and respect that life did that to you, etched lines of experience on you that said to the world, “I’ve been there, done that, and lived through it.”

On Catherine all that living only made her sexier.

“Hi,” she said and walked calmly into the room, which suddenly felt smaller and warmer.

Aly and Dana had come back downstairs earlier and had been talking to him. Well, Aly had been talking to him. Dana was sitting on the sofa, pretending to work on the puzzle when she wasn’t eyeing him like he was the Antichrist.

Catherine came over to the sofa in that same old long-legged walk of hers that after all these years could still get him hot and tight.

She poured herself a cup of coffee.

Aly scooted over and patted the spot next to him. “Sit here, Mom.”

“No!” Dana said so suddenly Catherine looked up from her coffee with a startled expression.

The only sound for that split second was the rain on the roof, tapping tensely. It was the kind of constant monotonous warning sound that made you follow it with your hearing sharp and your breath held, waiting for the explosion.

Catherine cast a quick apologetic glance at him, then gave a small shrug.

So this wasn’t Dana’s normal behavior with men, he thought. It was him alone and not just any man that made her oldest daughter so protective.

Catherine sat down next to Dana at the opposite end of the sofa. She looked up at him. “We were doing a jigsaw puzzle before the power went out.”

He nodded. “So I see.”

She looked at Dana, who was hunched over the table. “What piece are you looking for?”

“Steve Tyler’s belly button,” she said without looking up.

Catherine looked at him as if she didn’t know what to say to that, which Michael knew was why Dana had said it. Shock value.

He reached out and picked up a puzzle piece and held it out to her. “Here, try this one.”

Dana looked at it, then up at him, then took the piece.

It fit.

He winked at Catherine, who looked as if she wanted to strangle Dana. He shook his head slightly. It didn’t matter. Catherine needed to ignore her daughter’s behavior. It would work better than letting her teenager trap her into getting angry, which was Dana’s objective, even if she didn’t consciously know it.

The tension in the room was so taut you couldn’t have broken through it with two hundred pounds of muscle and a timber ax.

Aly was quietly sitting cross-legged next to him. She had a huge book propped in her lap and seemed oblivious to what was going on with her sister.

Catherine looked at her and asked, “What are you reading?”

“An encyclopedia.”

“Oh.” Catherine frowned. “Why?”

“I was just curious about something.”

“What?”

“Those slug things.” She looked up and grinned. “Slugs are just like you, Mom. They don’t have a mate.”

Michael choked on his coffee and tried hard not to laugh.

He had his answer. There was no man.

Catherine just sat there numbly looking like Christmas in her bright green sweater and her even brighter red face.

“It says here that they are mollusks.”

He caught Catherine’s eye and told her exactly what he had been thinking. “Not only does Aly look just like you did at that age, she is you.”

Catherine sighed and gave him a weak smile. “I know.”

Aly groaned and slammed the book shut. “Everyone says that.” Then she stopped and looked back at her mother. “Not that you aren’t pretty, Mom. It’s just weird, you know?”

“I understand, kiddo. At eleven you want your own identity, not your mother’s. I felt the same way. So did Dana.”

“And at school everyone knows I’m Dana Winslow’s younger sister. Mr. Johnson, the science teacher, even calls me Dana sometimes.”

Dana looked up then. “Do you answer him?”

“I have to. If I don’t he thinks I’m not participating.” Aly got up and trounced over to the bookcase.

There was another lapse of awkward silence.

Catherine took a sip of coffee. “So. The island hasn’t changed much, has it?” She didn’t look at him.

He should tell her now, that he had changed, that he wasn’t a handyman. He watched her and found himself staring at her hair. If she looks at me, he thought, I will tell her the truth.

She stared into her coffee cup as if she were searching inside of it for something to say.

Aly plopped back down next to him. “Mom says there’s plenty to do here. Fishing and sailing and stuff.”

Before he could answer Dana asked, “Do you have a boat?”

Michael nodded. “Yes.”

The girl brightened suddenly. “Good, then you can take us back to the mainland.”

“Dana!” Catherine looked at him then, clearly mortified. “I’m sorry. She seems to have forgotten her manners.” She paused and took a deep breath, clearly exasperated. “Dana doesn’t like it here.”

“There’s nothing to do here.”

Michael was quiet. He looked away from Catherine and into Dana’s sharp eyes. “The engine’s not running right.”

Dana looked like she didn’t believe him. “What’s wrong with it?”

Catherine groaned and buried her face in a hand, shaking her head.

But he answered her daughter. “The plugs are bad and the points need to be replaced.” He stood up then. “I should leave.”

Catherine stood up after him and followed him to the door as if she wanted to say something but didn’t know what. He could feel Dana watching them intently and figured she would have been walking in between them if she thought she could have gotten away with it.

He took his jacket off the hook and put it on, then stepped out onto the porch, sat on the bench and pulled on his boots.

Catherine was leaning against the door jamb with her arms crossed, watching him. She had one of those wistful smiles he remembered, the kind she had just before he used to grab her and kiss the hell out of her.

“The rain’s stopped,” was all she said.

He stood and took two steps to stand near her. He looked down at her face. “I’ve got good timing.”

“I’m sorry about Dana.” She dropped her arms to her sides. “These teenage years aren’t easy.”

He nodded, thinking that she was a teenager the last time he’d seen her.

They stood there like that, not saying anything that mattered. It was as if they were both afraid to say what they were thinking.

He looked away. “Thanks for the coffee.”

“Anytime.”

Neither of them spoke again for a long stretch of seconds. He felt like he was twenty again, standing on the same porch and wanting to touch her so badly he hurt with it. But knowing he couldn’t because her parents were right there on the other side of the door.

There were no parents this time; it was her children who were watching them, probably listening to them.