полная версия

полная версияMr. Punch's History of Modern England. Volume 2 of 4.—1857-1874

Mr. Laing talked nonsense about the ideal of woman, said that Juliet, Ophelia and Desdemona had nothing to do with votes – the poets understood woman better than Mr. Mill.

Sir George Bowyer, like a gallant knight, supported your cause.

Lord Galway said the motion placed admirers of the fair sex in an awkward position.

Mr. Onslow said that two young ladies had told him they would vote for the man who gave them the best pair of diamond ear-rings.

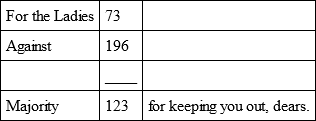

Mr. Mill was pleased, as well he might be, at the fearful debility of his opponents, and took the division, which was,

This speech of Mr. Mill's was the event of the week.

At any rate it cannot be said that Punch failed to do justice to the debate on its merits. His account is both ampler and fairer than many reports of important discussions in Parliament which appear in the daily press of to-day. But this was the day of verbatim reports. Punch mentions one debate which occupied thirty-six columns of closely-printed small type in The Times.

"Pray clear the way, there, for these – ah – persons."

By way of an offset to the admissions made in his Parliamentary report, Punch published a long, open letter to Mr. Mill. The argument founded on the derogatory word "person" need not detain us. The letter is signed "Judy," but the voice is the voice of Punch, who would not give women the vote because he believed they could exercise their political rights of sovereignty more effectually by proxy. Why should they wish to exercise power through the franchise when they were already omnipotent over those who had the franchise? Men were not much the happier or the better or the wiser for their politics. Mill's proposal to exclude married women from the franchise is dexterously turned to account as an admission that female influence was paramount as it was; that it was unnecessary to give women what they already exercised through their husbands. In fine, till women were married, they were learning to rule their husbands. After they were married they had their husbands to rule. Politics were the natural occupation of the inferior or slavish sex. When would Mill's logic open his eyes to the fact that, like the Constitutional Sovereign, la femme règne et ne gouverne pas?

Such a letter brought but cold comfort to the Suffragists. It was like feeding them with the East Wind. But at its worst it was an immense improvement on the heavy facetiousness of Punch's earlier manner.

In May, 1868, Punch virtually sided with his "dear enemy": —

Mr. Mill presented to the Commons a petition signed by 21,757 women, who asked for the Franchise. The first signature was that of Mrs. Somerville, Mechanist of the Heavens; the second that of Miss Florence Nightingale, Healer on Earth. Right or wrong, the request ought to have been granted to such petitioners.

Open Letter to Mrs. Fawcett

So when at a meeting in Manchester in December, 1869, it was resolved to form a guarantee fund of £5,000, Punch declared that if the Suffrage was to be had for love or money, women would shortly have it, and went on with characteristic effrontery to claim the credit of being "the Liberator of the Ladies": —

When ladies, ere many months shall have passed over their heads, rush to the poll and tender their votes for the men of their choice, let them not forget to whom they are mainly indebted for ability to exercise the birthright of a Britoness. It has ever been the aim of Mr. Punch to elevate Woman as well as Man. To this end he has directed pen and pencil to the special exposure of the peculiarities which distinguish silly from sensible women to derision. The consequence has been a very general relinquishment of those ludicrous peculiarities, and an awakening the female mind to logical perception, and a sense of the absurd and the grotesque. Hence will sooner or later inevitably result Female Emancipation, for which Female Intellect will have to thank Mr. Punch.

These indiscretions, which were apparently only meant in a Pickwickian sense, obliged Punch to regularize his position in a letter to "Mrs. Professor Fawcett" in the following April. He congratulates the Suffragists on dropping the limitation with which they started and going in for repealing the electoral disabilities of all women – married as well as single. In revising their claim they were at once logical and wise in their generation. But on the broad question Punch comes down on the anti-Suffragist side of the fence: —

Has it never occurred to you that in parcelling out life into two great fields, the one inside, the other outside the house-doors, and in creating two beings so distinct in body, mind, and affections as men and women, the Framer of the Universe must have meant the two for different functions? Can you deny, or shut your eyes to the fact that a similar distinction runs through the whole animal kingdom? Surely, so long as the masculine creature keeps aloof from the domain of the feminine, and leaves to her the nursing and rearing and training of the family, and the ordering and gracing of the home, there lies a tremendously strong presumption against the wisdom of the feminine entry on the masculine domain of business and politics.

The conclusion he comes back to is his old argument: Why give women votes when they have them already?

In a word here is my dilemma, dear Mrs. Professor. Either women don't care for votes – in which case they will make a bad use of them; or they do care for them, in which case they have ours.

Look how you rule in that Parliament for the business of which you do care, and whose budget you control and appropriate. What man dares call his home his own? What man, that deserves to be called a man, with a good wife, wishes to be other than her humble servant, breadwinner, hewer of wood and drawer of water, within the walls of that sacred sphere, of which the household hearth is the central sun? Depend upon it, if Nature had meant you for the franchise, you would have had it long ago. But then, if you had been in our place, we should have been in yours. Do you think it would be a better world for the change?

The worldly wisdom and common sense shown in this letter is also to be found in Punch's review of the whole question of Women's disabilities in the same year. The facetious, patronizing tone is largely dropped, and though the cartoon on the "Ugly Rush," inspired by the rejection of Jacob Bright's Suffrage Bill, clearly approves of the result, it fully recognizes the seriousness of the onslaught on man's monopoly of the franchise. The time for chaff on the subject, as Fawcett said, had gone by.

Short of the vote, however, about which he remained recalcitrant, Punch supported the claims of women to official employment in connexion with the Poor Law, Education, Local Government generally. He bestows a tempered approval on the appointment of Women Parish Officers in Bucks in 1868, and when the first elections to the London School Board were held at the close of 1870, unofficially but strenuously championed the three women candidates – Miss Garrett, M.D., Mrs. Grey and Miss Davies: —

There are some very good men in the candidature, but they are well known, and can speak for themselves. Mr. Punch only wishes to point out that three ladies desire to do Woman's Work, and he hopes that they will be accredited to the Board. He seldom condescends to treat of mere political elections, but these Educational Elections are important, and wise men had better look to them.

Mr. Bull: "Not if I know it!" (See Division on the Woman's Vote Bill.)

Mrs. Nassau Senior

The appointment of Mrs. Nassau Senior by the President of the Local Government Board to inspect and report on pauper schools, and her contribution to the Third Annual Report of that Department, meet with unqualified approval: —

In the midst of that vast blue-book of seven hundred pages there is a bit of motherly writing by Mrs. Nassau Senior, which is delightful to read, and cannot fail to be of immense use. Mrs. Senior has visited pauper schools, and has traced about seven hundred girls who had been educated at pauper schools; and her brief biographies of these poor little waifs are perfect in their simplicity. She believes that the Poor Law system will, in time, come to an end through improvement in education. Mr. Punch is not so sanguine. Mendicity is eternal. But the pauper may be gradually raised to a higher level; and such an inquiry as Mrs. Senior's is likely to do great good in this way.

Mr. Punch is delighted when a lady does in this direction what no man could possibly do. The terse memoirs of these poor little pauper maids are much more pathetic than anything in modern fiction. We trace the poor children from place to place – we see them stunted, sulky, squinting, suffering from ophthalmia, the very refuse of the world. Mrs. Senior, kind and keen in her investigations, tells the Guardians of the Poor (who too often deem themselves mere guardians of the ratepayers) how they may gradually diminish this evil. Mr. Stansfeld did a wise thing when he asked her to undertake the inquiry; if the lessons of it are rightly read, her second contribution to the blue-book will have a far rosier tinge.

The treatment of the Higher Education of Women follows much the same course – from ridicule to respect. When a Women's Library was founded in New York, it is seriously suggested in 1860 that a similar institution might with advantage be established in London, with Miss Bessie Parkes, who was an active promoter of the Social Science Association, as Librarian. But when in the summer of 1862 Mlle. Emma Chenu was admitted to the degree of Bachelor of Science at the Sorbonne, Punch contents himself with drawing up a burlesque list of Lady Professors for the University of Cambridge, most of them popular actresses of the time, including Marie Wilton, Patty Oliver, Lydia Thompson, etc. By way of contrast to this carnival of punning facetiousness we may note the rebuke administered in May, 1863, to the students of University College, who hissed the proposal to admit women to degrees.

Girton College

Great capital was made out of "Sweet Girl Graduates" by Du Maurier in many characteristic variations on the "Princess Ida" theme. But the movement was rapidly passing beyond the stage in which it could only be treated sentimentally or in a spirit of ridicule. Huxley was lecturing to women at South Kensington in 1870, and in 1871 the Ladies' College at Hitchin (founded in 1869), which owed its origin to the enterprise and liberality of Madame Bodichon – the friend of George Eliot and the zealous advocate of the improvement of women's position in the state – had so far justified itself as to earn Punch's commendation, under the typically frivolous heading of "The Chignon at Cambridge," a good example of inept alliteration's artless aid: —

At the examination lately held at Cambridge a number of students from the Ladies' College at Hitchin passed their "Little-go"; the first time that such undergraduates ever underwent that ordeal. It is gratifying to be enabled to add, that out of all those flowers of loveliness, not one was plucked. Bachelors of Art are likely to be made look to their laurels by these Spinsters, and Masters must work hard or they will be eclipsed by Mistresses, more completely than the Sun was the other day by the Moon. And we may expect that when such competitors of both sexes come to perform upon the classical and mathematical Tripos, a Pythoness will be first upon the former, and another young lady will dance off triumphantly Senior Wrangler.

Punch's prophecy was fulfilled by the exploits of Miss Ramsay (afterwards Mrs. Montagu Butler) and Miss Philippa Fawcett, daughter of Henry and Millicent Garrett Fawcett. The College at Hitchin was moved to Cambridge in 1873, when it entered on a new and prosperous career under the title of Girton. But Punch, reverting to his facetious manner, availed himself of the opportunity to publish a set of burlesque regulations and syllabus of lectures for the new College. The same spirit is betrayed in the comments on the proposed Ladies' Club in 1869: —

A Ladies' Club is said to be in process of formation. How the male mind shudders at this most tremendous news! What a field for fearful questions the intelligence suggests! Will there be a Club Committee? and, if so, at its meetings how many ladies' tongues will be allowed to speak at once? Will there be a smoking-room? And, if so, will cigars be suffered to be lighted, or will the fear of being ill restrain the ladies from indulgence in anything except the very mildest cigarettes? Will conversation be restricted to the politics of the nursery and the latest news in bonnets; or what will be the limits sanctioned to recounters of a thrilling bit of scandal, or to narrators of a tale of love, or marriage, or divorce, which has just been set a-wagging in high life? Instead of billiards we presume the younger members will amuse themselves with tatting, while the elder are engaged in a fierce battle at Bézique…

The ladies will, of course, want a title for their Club. Perhaps "The Femineum" would be a fitting name for it; or would its members prefer to call themselves "The Chatterers" while the present fashion lasts? Should the Ladies' Club prove popular, there may doubtless be some little ducks desirous to belong to it. But we trust, however silly may be certain of its members, nobody will ever dream of calling it "The Goose Club."

The promoters might have retorted that such criticisms were worthy of the members of the "Asineum." But Punch was fairly entitled to make such capital as he could out of the advertisement quoted in 1874: "Philosopher wanted, as Secretary to a Ladies' Club."

The Economics of Marriage

As we have seen, Punch had frankly recognized that matrimony was not and could not be the be-all and end-all of all women – that there were some girls who, though they might marry if they chose, did not wish to; girls who preferred independence to matrimonial servitude; girls, again, who would make excellent wives, but were not chosen because men were stupid enough to be governed in their choice by looks and looks alone. The economics of marriage, again, were becoming an increasingly important consideration as a result of the raising of the standard of life and the cost of living. In the 'forties Punch printed a song of which the refrain was "If I had a thousand a year," which represented a sum almost beyond the dreams of middle-class avarice, to judge by all the things the dreamer would do and all the luxuries he would indulge in, if his income reached four figures. In 1858 The Times started a serious discussion of the problem "Marriage on £300 a year," which the same audience nowadays would regard not as practical politics but an act of insanity. Punch, however, satirized the discussion from the point of view of an agricultural labourer earning a wage of 10s. a week.

Though in the golden days of Gladstonian finance the income tax came down to 4d. and even 3d. in the pound, the standard of living rose, and £500 a year is mentioned in 1867 as a possible basis for matrimony. From whatever the cause – possibly the prevalence of large families had something to say to it – the rapidity with which married people of both sexes grew old, as compared with the juvenile grandparents of to-day, is strikingly illustrated in the pages of Punch. Take for example the two pictures "Twelve months after Marriage" and "Twenty years after Marriage" in 1862. When we take into account the earlier age at which people married sixty years ago, the couple in the picture on p. 265 need no be more than forty-five; yet they both look at least seventy. One is reminded of a passage in Sense and Sensibility (though, that, of course, was fifty years earlier), in which John Dashwood, speaking of his mother, who is "hardly forty," suggests that "she may live another fifteen years." The pictures given here represent a happy marriage. Punch had no panacea for unhappy marriages; but he remained of the same opinion, so often expressed in his earlier days, that a cheap Divorce Act was a better cure than the punishment of cruel wife-beaters. And throughout this period he remained constant in his support of the campaign for the amendment of the Women's Property Acts, on the lines of his summary of Lord Brougham's three resolutions moved in the House of Lords on February 13, 1857. They were "First, that their present rights were all wrongs. Second, that a woman was entitled to her own property; and third, that if our ridiculous theory of marriage prevented a woman from having this justice, at all events a profligate husband should be restrained from wasting her possessions." Lastly, he remained unshaken in his adhesion to the cause of marriage with a deceased wife's sister, or, as he termed it, "the Bill for Emancipation of Sisters-in-Law from the tyrannical disqualification which prevents their taking the matrimonial oath when elected by a Briton and a widower."

"Bobby ought to love his pet for taking such care of his beautiful whiskers."

The English Feminine Type

By way of conclusion we may add that if Punch reserved to himself the right of castigating the follies of his countrywomen, he was valorous in their defence when they were depreciated or caricatured by foreign critics or artists. In 1858 he falls foul of a German journalist, under the head of "British and German Beauty": —

The Berlin Charivari contains the following humorous remarks on English beauty: —

"Each Nation thinks itself the handsomest in the world. We paint the devil black; the blacks will have him white. Miss Pastrano delights in her beard, and every Englishman thinks his red-haired, crooked-nosed, rabbit-toothed, goggle-eyed, loose-legged, calfless Dulcinea the very perfection of human beauty."

Not quite that. Not so perfect as the raven-haired, Grecian-nosed, white-and-sound-toothed, sloe-eyed, neat-legged young Teutonic lady, with such pretty little feet and ankles at the end of her legs. Of course the Prussian Charivari's notion of an English girl is a bit of fun, complimentary irony; and we are sure our fair countrywomen will feel highly honoured by the mock-depreciation of our cousin German.

Much later on the French caricaturists, who habitually represented Englishwomen as lean, gaunt, ill-favoured and ill-dressed, and with long projecting teeth, roused him to protest with equal vigour against their gross and unseemly libels.

"My dear Bobby, you must let me pull it off your nose; it looks so ugly."

LITERATURE

There is probably no better means of testing a man's literary sense than his estimate of poetry other than that written by authors of established reputation. And as with individuals so is it with papers. Punch deserves no special credit for his devotion to Shakespeare, or for his ridicule of the Baconians who, in his phrase, sought to make the Swan of Avon a Goose. It is curious, however, in this context to note that, on Punch's authority, Lord Palmerston suspended judgment on the question. In the arm-chair commentary on current events which appeared in 1865 under the heading, "Punch's Table-Talk," we read: —

When Ben Jonson's verses, in laudation of William Shakespeare, were mentioned to the late Premier, he said, "Oh, these fellows always stand up for one another. Besides, he may have been deceived like the rest."

It is only one and a small proof of Shakespeare's "myriad-mindedness" that Punch throughout his career has drawn more freely from his plays for subjects for cartoons than from any other source. Shakespeare, as a modern writer puts it, "has always been there before." It was partly no doubt due to Punch's distrust of the national capacity to organize and carry out picturesque demonstrations that led him to treat the Shakespeare Tercentenary Celebrations in 1864 with scant respect. But an honourable jealousy for the repute of our greatest writer was enough to warrant his dissatisfaction. There were wide divergences of opinion and considerable friction among the members of the National Memorial Committee, a huge unwieldy body representing all professions and interests, and containing, along with many great and honoured names, not a few thrusting notorieties and even nonentities. The festival at Stratford was a fiasco, and the grandiose schemes of the promoters came to little practical result. One is indeed tempted to draw the conclusion that it is almost unnecessary to attempt a special celebration of one who is being celebrated every day and all the time.

As a critic of letters Punch is subjected to more searching ordeal in his references to living and rising than to dead or risen authors. His recognition of James Montgomery – the author of one of the very few fine modern hymns – has been noticed elsewhere. There was chivalry as well as appreciation in his defence of Alexander Smith when the charge of plagiarism was brought against the "City Poems" by the Athenæum. The ridicule of the "Spasmodic" school in Aytoun's brilliant burlesque drama Firmilian was a much more damaging criticism, but in recognizing Smith's force and originality Punch ranges himself on the side of Clough and Matthew Arnold, John Forster, Arthur Helps and G. H. Lewes – in other words, the most enlightened and best equipped critics of the time.

Though Tennyson had been Laureate for several years, he was still regarded – surprising and even painful as it may seem to the neo-Georgian reader – with a certain amount of suspicion by austere critics bred up in eighteenth century traditions. Both as regards matter and manner he was considered to be an innovator. Punch's admiration for Tennyson was already an old story. He had lent him the hospitality of his pages in 1846 to reply to Bulwer Lytton's defamatory abuse in The New Timon. But in some quarters judgment was still suspended, and Tennyson was not yet held to have completed the period of probation. So when in 1859 the bust of the Laureate was denied admission to the Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, on the ground that the honour was premature, Punch printed a satirical "Fragment of an Idyll" in which the poet's detractors were rebuked in his own manner.

A Wonderful Three-penny-worth

Punch's championship of Tennyson never faltered, though he was reconciled to Bulwer Lytton, who had called the Laureate a "School-miss," and it dated back to a time when Tennyson's claims to recognition were vehemently canvassed. Still we are inclined to regard as a much more remarkable sign of his flair and enlightenment, the quoting of Meredith's poem, Modern Love, in his "Essence of Parliament," in the year 1865. It is only a scrap – four words; yet when one remembers how remarkably small Meredith's audience was in the 'sixties, even for his prose, the quotation is a notable sign of grace. But Shirley Brooks, who distilled the "Essence," was a scholar and something of a poet into the bargain. There was also a special bond between Punch and George Meredith. In 1860, under the heading "An Honest Advertisement," Punch refers to Once a Week as having been enlarged to thirty-two pages, and speaks of it as "already one of the most extraordinarily cheap publications in the world when you consider the brilliancy of the literature and the beauty of the illustrations." This was admittedly a puff, for the proprietors of Punch and Once a Week were the same, but it was no more than the truth. Once a Week was the most wonderful three-penny-worth in the whole journalistic history of the nineteenth century, with Millais, Rossetti, Sandys, Frederick Walker, G. J. Pinwell and Charles Keene as regular illustrators. As for the letterpress, it is enough to say that Meredith's Evan Harrington (illustrated by Charles Keene) appeared in its pages, as well as many of his and Tennyson's poems. In spite of this galaxy of talent the magazine was not a commercial success, and after a few years passed into other hands.