полная версия

полная версияIn the Land of Mosques & Minarets

The young girl asked what might be her wooer’s position in life, whereupon his friend replied: “He is a warrior; when the fight is at its thickest, it is he who cleaves a passage through the ranks of the foe. He is taciturn and sober and knows well how to take adversity.” This seems a good enough send-off for a proxy to give, but the maid would have none of it. She said simply: “Go back to your friend. It is a lion that you tell me of. He wants a lioness, not a woman. I would not suit.”

The suitor for a young girl’s hand among the Arabs often does make his demand of her parents by proxy; and much bargaining and giving and taking of concessions goes on, all without embarrassment to the swain. It’s not a bad plan! A contract follows, and finally legal sanction. Every Mussulman marriage must have the consideration of the dot as a part of the legal agreement. The dot may vary with the fortunes of the girl’s family, or with the condition of the suitor; and, in case of divorce, this dot must be returned to the unfortunate lady’s parents, not to her, whatever may be the cause.

The wedding trousseau of the young wife, that which she brings in the way of clothes and jewelry, must comport with her former station in life; but her dot, which may be in kind, not necessarily in money, may be as great as the prospective husband can worm out of the girl’s parents. A rich Arab of the “Great Tents” whom we heard of at Jouggourt gave up the following: Three camels, fifty sheep, eighteen skins, three bolts of cotton cloth (made in Manchester – the “Manchester goods” of commerce as it is known in the near and far East); a gun (a Remington so-called, most likely made in Belgium), with brass and silver inlaid in the stock; two pairs of silver rings for ankles and wrists; two buckles for the haïk, a silken burnous, a silk sash, a string of coral beads (made of celluloid at Birmingham), earrings, a mirror (of course) and a red haïk, and a melhafa or haïk of cotton.

Among the desert tribes the women of all classes of society frequently have their faces unveiled; but, as they approach the great trade-routes and the cities, they closely enwrap the face so that only a pair of glittering black eyes peep out. Without regard to class distinctions or age all Arab women are passionately fond of jewelry of all kinds, finger-rings, anklets, bracelets, chains, and brooches.

Repudiation, or divorce, is legal among the Arabs if accomplished in a legal way, and is simply and expeditiously brought about. The following is an account reported recently in an Algerian journal: —

El Batah had presented himself before the Cadi for the purpose of “repudiating” his wife, “une femme grande et forte, d’une éclatante beauté.” “Well, what is it?” said the Cadi, scenting in the affair a big fee, at least big for him. The Cadi was very much smitten by the lady, it appears, though he did not know it, or at any rate admit it, at the time.

“I come to complain of my wife, who has beaten me and nearly broken in my head,” said the poor man.

“It is true,” echoed the woman, “but I did not mean to do it, I am sorry; I ought not to be punished.” (This doesn’t seem logical, does it?)

“Well, I shall ‘repudiate’ her” said the man; “I will have none of her.”

“Return her dot, then, to her family,” said the Cadi.

“Great Allah! It is impossible, it is four thousand dirhems, how can I pay it?”

By this time the Cadi saw his fat fee vanishing, and his ardour for the lady of the striking beauty rising. He had just lost his fourth wife, the Cadi, and there was a place in the ranks for another.

“If I will give you the sum,” said he, “will you ‘repudiate’ this woman?”

“Yes, willingly,” said the fellow.

“Well, here’s your money,” said the accommodating official.

No consideration of the women of North Africa ought to terminate without a reference to the Mauresque, that gracious type found all through Northwestern Africa, a product of the mixture of the races, an outcome of civilization and the growth of the great cities of the seaboard. They are usually named Fathma, Zohra, Aicha, Houria, Mami, Mimi, Roza, Ourida, Kheira, etc.; and they leave the bed and board of their parents usually between the ages of twelve and fourteen to be married, or for other reasons. Practically all the world looks upon the Mauresques as social outcasts. The class had become so numerous about the middle of the nineteenth century that the hand of philanthropy was held out to them to enable them to better their condition in life. They were given a rudimentary book education, and were taught the art of Oriental embroidery with all its extravagance of capricious arabesques and threads of gold.

As for the other class of Mauresques, the rikats, those who have become contaminated, – for not all are saved, nor ever will be, – one recognizes them plainly as of the world worldly whenever they take their walks abroad. The sad amusement of visiting mosques and cemeteries is not their sole pleasure, as it is that of the legitimate Arab wife, or Mauresque, even though her spouse be wealthy.

The Mauresque partner de convenance of a wealthy indigène or European may have her own horses and carriages, perhaps by this time even her own automobile; and rolls off the kilometres in her daily promenades on the fine suburban roads of Algiers, in company with the haute société of the city, and the thronging American, English and German tourists from Mustapha. She even dines at the cabarets of Saint Eugène, Pointe Pescade or the Jardin d’Essai, and no one does more than look askance at her. Algiers is very mondaine, and its morals as varied as its population.

Even though the rikat dresses after the European mode, there is no mistaking her origin. Her great, snappy black eyes, livened and set off by dashes of koheul, are fine to look upon; and her figure, as she sits in her cabriolet or opera-box, is so well hidden that one does not realize its cumbersomeness. At home she wears the seraglio “pantalon” of the Arabian Nights, ankles bare and feet stuffed into babouches– which an Indian or a plainsman would call moccasins. Over all is the r’lila, a sort of cloak of gold-embroidered, silken stuff, very light and wavy. It’s not so graceful as the kimona of the Japanese, but it’s far more picturesque and useful than the most ravishing tea-gown ever donned in Fifth Avenue or Mayfair.

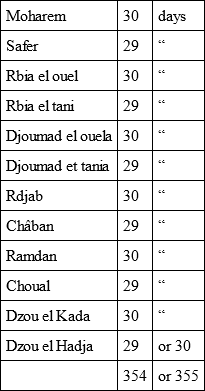

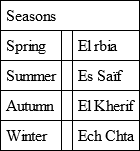

The Mussulman calendar is simple, and, except in the nomenclature of its divisions, is not greatly different from our own. The Arab year has twelve lunar months, making in all three hundred and fifty-four or three hundred and fifty-five days.

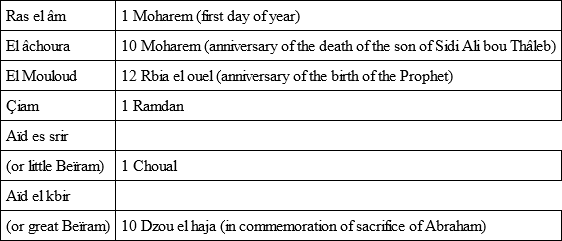

The principal fêtes of the Arab are those of the Mussulman religion, the same one observes in Bombay, Constantinople and Cairo.

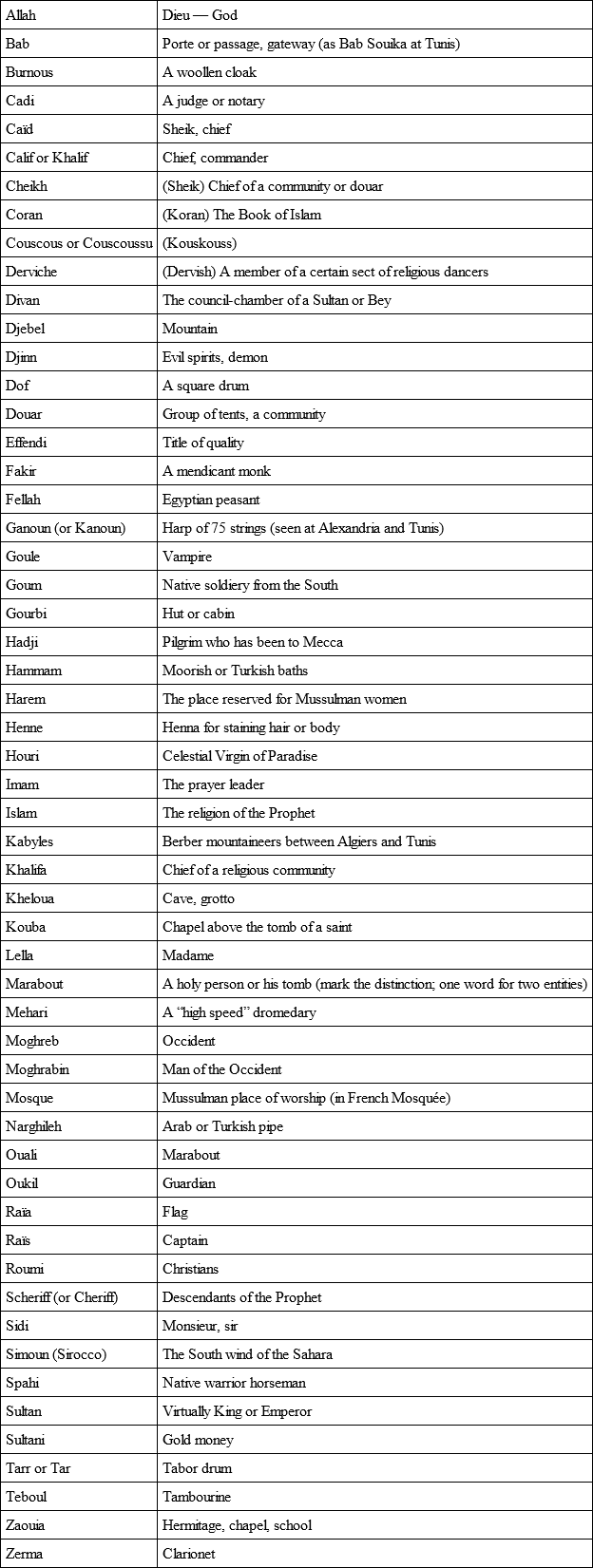

The following glossary of commonly met with Arab words is curious and useful: —

CHAPTER X

“THE ARAB SHOD WITH FIRE”

(Horses, Donkeys, and Mules)AS a Kentucky colonel once said, the pure-bred Arabian horse is a fine thing in his native land; but there is more good horse-flesh, per head of population, in the United States than the first home of the ancestor of the blooded horse ever possessed. Everything points to the fact that the gentleman knew what he was talking about, as fine specimens of Arabian horse-flesh are rare to-day, even in Arabia and North Africa. They exist, of course, but the majority of horses one sees in Algeria and Tunisia are sorry-looking hacks.

In the desert the case is somewhat different. There the beautiful Arabian horses of which romance and history tell are more numerous than the diminutive bronchos of the coast plains and mountains. The descendants of the Anazeh mares, the parent branch of royal Arabian blood, are not many; but an Arab of good lineage may still be had by one who knows how to pick him out, or gets some friendly Sheik to give him his.

No one seems to know where the original Arabian horse was bred, though it was known in the Mauritania of the Romans, in the environs of Carthage, long before that little affair of Romulus and Remus startled an astonished world. In all probability he was a descendant of the same horses which made up the Numidian cavalry which overran Rome during the Punic wars, and that’s a pretty ancient pedigree.

To-day all through North Africa, in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Tripoli, Egypt, and in Arabia across the Red Sea, the type is recognizable in all variations of purity and debasement.

The “Arab shod with fire” of the Bedouin love-song may not be all that sentiment has pictured, but he is an exceedingly high-bred animal nevertheless.

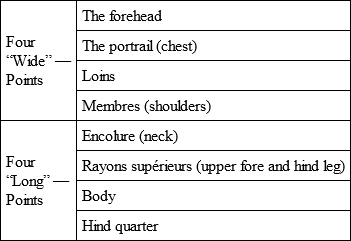

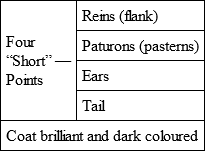

Here are his fine points: —

This is the formulæ upon which the French remount officers choose their Arabian horses, and for hard work they take always a “traineur avec sa queue,” a horse of seven years or more.

Each chief of an Arab family possesses one or more of the blooded Arabians of classic renown. It is his friend in joy and sorrow, and his constant companion when he is away from his family. If the Arab chief has many horses he always keeps one, the favourite, as a war-charger. If there are no wars or rumours of war in sight, he only rides this favourite on gala or parade occasions; but at all times he gives it more care and attention than many heads of families, in more conventionally civilized lands, give their wives. The Arab knows the ancestors of his horse as well as he knows his own; and he has its pedigree writ on parchment, which is more trouble than he has taken to perpetuate the memory of his own remote parents. The Algerian Arab horse has been called a “mixed-pur sang,” whatever that may mean, but certainly it will take somebody more expert than a mere “horsey” person (the kind that go around talking about their “mounts” and how “fit and saucy” was the one they rode that morning) to mark the distinction between the best of the Algerian variety and those of Egypt, Syria or Arabia.

The Arab trains his horses for his own personal use, to pace, canter, or gallop, never to trot, a gait which is only fit for the European who is afraid to sit on, or behind, a horse with a quick-moving pace. This is the Arab version of it, and an Arab horse owner will hobble his beast with a rope if he shows the least inclination to trot or single foot. If this won’t break him, why he sells him to some one who will stand for it – at the best price he can get. The Arab horse owner thinks with the late A. T. Stewart: “If you have got a loss to meet, meet it at once and get your capital working on something else.”

The writer recently met an Italian trying to bargain with an Arab for a saddle-horse. The Arab was with difficulty convinced that the gentleman was not an Englishman who would buy only a “trotting saddle-horse.” Quel horreur! “Allah be praised!” said Ali-something-or-other, the trader, all Europeans are not imitators of the English taste in saddle-horses. Once in awhile an Italian or a Spaniard or a Frenchman wants a horse for a carrousel and not for an amble in the Bois, which is his idea of doing as they do in London.

The reputation of the blooded Arabian horse, whether it is found in Arabia, Algeria or Morocco, is classic, and the mule, too, seems here to take on qualities not its birthright elsewhere. With the donkey, the petit âne with a cross down its back and a silver museau, the same thing holds good. North Africa is the donkey’s paradise. Here, if he finds herbage scant once and again, he thrives as nowhere else, and attains often an age of thirty-five years. The donkey in Africa is worked hard, but is neither unduly maltreated nor misunderstood. Perhaps that is why he lives long, though if the present race of donkey boys, who have been trained at the Paris and Chicago exhibitions, go on their unruly ways now they have got back to their homes at Cairo, Tunis or Algiers, even the patient, sad little donkeys may take on moods that hitherto they have never known.

The horses and donkeys of the big towns may well become spoiled by vanity, for they are often the subjects of an assiduous and inexplicable care on the parts of their owners, who comb their locks, and braid them, and cosmétique them and put rouge on their foreheads, and even stain them with henna until they are a regular “Zaza” tint. Darkest Africa is not so backward as one might think!

All classes of native riders, whether on the camel, mehari, horse, mule, or donkey, beat the ribs of the creature with a heel-tap tattoo in what must be an annoying manner for the beast. From the way the native, rich or poor, sits on his horse, spurs would be of no use to him, and only the Spahi, or native cavalry, has adopted them.

Donkey riding is the same dubious rocheting proceeding in all Mediterranean countries. It is no worse here than in Greece or on the Riviera. “The donkey’s a disgrace,” says the Arab; and he runs along behind, beating his onery little beast and calling it a fille de chacal, a graine de calamité or a chienne. This need awaken no sentiments of pity whatever – for the donkey. They are as much terms of endearment as the occasion calls for. The most common four-footed beast of burden in Algeria is undoubtedly the despised donkey of tradition. Every one does seem to despise the donkey, except the Mexican “greaser,” who asks as affectionately after his neighbour’s burro as he does his wife or children. Here the bourriquet or h’mar is quite a secondary consideration in the Arab’s domestic entourage.

The bourriquet is an economical little beast, costing only from ten francs upward. He usually feeds himself, browsing as he goes, and trots twenty or thirty kilometres a day, encouraged by the whacks and expletives of his driver who may often be found perched on top of the donkey’s load of a hundred and fifty pounds or more.

To us it all savours of cruelty, and perhaps some real cruelty does take place; but much of the “coaxing” of a donkey into his gait is necessary, unless one is disposed to let him stand still for hours at a time, too lazy to do anything but swish and kick the flies away. Æsop’s ass prayed to Jove for a less cruel master, but that deity replied that he could not change human nature nor that of donkeys, so things were left to stand as before.

The Arabs often slit the nostrils of their donkeys, on the supposition that the Maker did not fashion them amply enough to allow them to breathe readily. The more readily the donkey breathes, the more capable he is to carry heavy burdens long distances. Logical, this! And the procedure, too, improves the tonal quality of the donkey’s bray. Well, perhaps, though most of us are not devotees of that sort of music. Compared to Italy or Spain, there are considerably fewer suffering sore-backed donkeys in Algeria or Tunisia.

There is no question but that for economical service the donkey will kill any horse or mule; and it is clear that, weight for weight and load for load, he daily outdoes the camel. The latter, weighing fifteen hundred pounds, carries perhaps a weight of three to five hundred. The ass weighs two hundred and fifty to four hundred pounds, and, carrying one hundred and fifty to two hundred, outpaces the camel by a mile an hour.

The donkey is guided by the voice, a stick, or a rope halter, which lies on the left side, and is pulled to turn him to the left, or borne across his neck to turn him to the right. The stick serves the double purpose of striking and guiding, and the stick must needs come into play only too often.

The donkey here in the Mediterranean countries is often very small, not thirty-two inches in many cases, no bigger than a St. Bernard. When one hires a donkey to carry him over an étape on some mountain road, it is often a beast from whose back one’s toes touch the ground, though one is seated on a pad, not a saddle, and measures only five feet seven.

CHAPTER XI

THE SHIP OF THE DESERT AND HIS OCEAN OF SAND

A CAMEL may be a cumbersome, ungainly and unlovely creature, and may be destined to be succeeded by the automobile, to which he seems to have taken a violent dislike; but there is no underrating the great and valuable part which he has played in the development of the African provinces and protectorates of France. He has borne most of their burdens, literally; has ploughed their fields, pumped their water, and even exploited the tourists, to say nothing of having been the companion of the Mussulman faithful on their pilgrimages.

The camel caravans which set out across the desert from Tlemcen, Tunis, and Constantine (there are no camels nearer Algiers than Arba) are in charge of a very exalted personage, – or he thinks he is. His official title is gellâby. Each and every beast of burden is loaded to the limit, and pads his way with his great nubbly hoofs across untold leagues of sand or brush-covered soil without complaint. At every stop, however, and every time a start is made, he always gives vent to shrieks and groans; but as this procedure takes place at each end of a day’s journey as well, it is probably pure bluff, as the camel-sheik claims. To one unused to it the noise seems like the wails which are supposed to come up out of the inferno.

The camel of Africa, so-called, is really not a camel, he is a dromedary; the camel has two humps, the dromedary but one, but camel is the word commonly used. The two-humped quadruped, then, is a camel, – the direct descendant of the camel of Asia, whilst that of the single hump is the dromedary of Africa. The distinction must be remembered by all who talk or write on the subject, with the same precision that one differentiates between African and Indian elephants.

The camel has by no means the rude health and strength which has so often been attributed to him, indeed he is a very delicate beast and demands a climate dry and hot. Cold and snow and persistent rains are death to a camel. A camel must be well nourished, and with a certain regularity, or he soon becomes ill and dies. He is easily frightened and can spread a panic among his fellows with the rapidity of wild-fire.

For the most part the camel is kindly and temperate, but he can get in a rage and can be very dangerous to all who approach him on foot.

The camel of the south cannot live in the north and vice versa. They are not acclimated to the varying conditions. One judges a good camel (dromedary) by his hump; firm and hard, it is a sure sign of a good-natured, hard-working, friendly sort of a camel; if flabby and mangy, then beware.

A camel eats normally thirty or forty kilos of fodder a day, and must be allowed four hours to do it in. As to drink, once in two or three days in summer is enough, but in winter he can go perhaps ten days, and his food bill is increased nothing thereby.

He can carry 150-160 kilos, a parcel hung over each side in saddle-bag fashion. The mehari, or long-distance, fast-gaited camel of the Sahara, is to the ordinary dromedary what a blooded Arabian is to a Percheron. He can better stand hunger and thirst, and on an average needs drink only once in five days; furthermore is not as liable to fright as is the djemel, as the Arab calls the camel, and is more patient and more courageous. Less rapid than a race-horse for short distances, the mehari, well-trained and well-driven, can make his hundred kilometres a day, day in and day out.

The saddle is called a rahala and has a concave seat, a large, high back, and an elevated pommel. The rider sits in the bowl-like saddle, his legs crossed on the beast’s neck. The mehari is driven through a ring in its nose, to which is attached a rope of camel’s hair. The beast is somewhat difficult to drive, more so than the djemel, and only its master can get good results. To mount, the beast kneels as do ordinary camels.

En route the mehari does not graze, but waits for a decent interval and takes its meal comfortably. A mehari, not accustomed to the sight of a horse, is often put into a terrible fright thereby. The education of a mehari is very difficult; it takes a year to break one.

The policing of the great Saharan tracts would not be possible without troops mounted on mehara, – the plural of the word mehari, – and France owes much of the development of her African provinces to the mehari and the slower-going camel.

The dromedary, or camel, as it is referred to in common speech, was an importation into Algeria away back in some unrecalled epoch, at any rate anterior to the Arab invasion of the eleventh century.

The mehari was a warlike beast as far back into antiquity as the days of Herodotus, Tacitus, and Pliny. Herodotus, recounting the battle of Sardes, said, according to Pliny: “Camelos inter jumeuta pascit Oriens, quorum duo genera Bactriani et Arabici…”

If an Arab is owner of a thousand camels, he wards off any evil that may befall them by leading out the oldest and blinding it with a rod of white hot iron.

A camel that has fallen ill may be cured, many superstitious Arabs believe, by allowing it to witness the operation of searing the hoofs of another, tied and thrown upon the ground. This is auto-suggestion surely, though where the curative powers come in it is hard to see.

When a bayra, a female camel, has given birth to five camels, the last being a male, her ears are bored and she is sent out to pasture, never more to be put to the rough work of caravaning. Like putting an old horse to pasture in perpetuity, it seems a humane act, and it solves the race question in the camel world, or would if the camels only knew the why and the wherefore.

The camel’s feet are admirably made for the sands of the desert; they form by nature a sort of adapted ski or snow-shoe. The hoof (though really it is no hoof) is bifurcated and has no horny substance, merely a short, crooked claw, or nail, at the rear of each bifurcation, a sort of elastic sole – the predecessor of rubber heels, no doubt – covering the base. The camel travels well in sand, but with difficulty over stony ground, where frequently the Arabs envelop his feet with cloths or leather wrappings.

The camel possesses further four other callosities, one on each knee, and he uses them all four every time he gets up or lies down. These callous places are something the beast is born with; they get ragged and mangy-looking with time, but they are there from birth.

The boss, or hump, of the camel-dromedary is mere gristle; it contains no bone, and is more or less abundant according to the health of the animal.

A well-fed and happy camel, starting out on a long march, regards his well-rounded hump with pride. Excessive travel and forced marches diminish its shape and size and the beast seemingly becomes ashamed and literally feels sore about it. But, like the conquered general on a battle-field who loses his sword, he ultimately gets it all back again, and a little rest, a change of diet, and a good, long drink – “a camel’s neck,” you might call it – makes a difference with the camel and his hump in the course of a very few days.

A camel gets unruly and cries out at times, and often becomes unmanageable, but an application of a sticky gob of tar or pitch on his forehead usually quiets him down.

The baby camels usually come into the world one at a time; and can stand up on their four legs the first day, and run around like their elders at the end of a week.