полная версия

полная версияIn the Land of Mosques & Minarets

Paper money, in values of twenty and fifty francs, takes the place of gold; the Arab thinks that it is something that is perishable, and accordingly spends it and keeps the country prosperous. The French understand the Arab and his foibles; there is no doubt about that. They solved the question of a circulating currency in Algeria. New York and Washington representatives of haute finance might take a few lessons here.

With regard to the money question, the stranger in Algeria must beware of false and non-current coin. Anything that’s a coin looks good to an Arab, and for that reason a large amount of spurious stuff is in circulation. It was originally made by counterfeiters to gull the native, but to-day the stranger gets his share, or more than his share.

To replace the gold “louis” of France, the Banque d’Algérie issues “shin-plasters” of twenty francs. They are convenient, but one must get rid of them before leaving the country or else sell them to a money changer at a discount. These Algerian bank-notes now pass current in Tunisia, a branch of the parent bank having recently been opened there.

The commercial possibilities of Algeria have hardly, as yet, begun to be exploited, though the wine and wheat-growing lands are highly developed; and, since their opening, have suffered no lack of prosperity, save for a plague of phylloxera which set back the vines on one occasion, and a plague of locusts which one day devastated almost the entire region of the wheat-growing plateaux. It was then the Arabs became locust-eaters, though indeed they are not become a cult as in Japan. With the Arab it was a case of eating locusts or nothing, for there was no grain.

This plague of locusts fell upon the province of Constantine in 1885, and from Laghouat to Bou-Saada, and from Kenchela to Aumale they were brought in myriads by the sirocco of the desert from no one knows where.

For two years these great cereal-growing areas were cleared of their crops as though a wild-fire had passed over them, until finally the government by strenuous efforts, and the employment of many thousands of labourers, was able to control and arrest the march of the plague.

During this period many of the new colonists saw their utmost resources disappear; but gallantly they took up their task anew, and for the past dozen years only occasional slight recurrences of the pest have been noted, and they, fortunately, have been suppressed as they appeared.

Besides wheat and wine, tobacco is an almost equal source of profit to Algeria. In France no one may grow a tobacco plant, even as an embellishment to his garden-plot, without first informing the excise authorities, who, afterwards, will come around periodically and count the leaves. In Africa the tobacco crop is something that brings peace and plenty to any who will cultivate it judiciously, for the consumption of the weed is great.

Manufactured tobacco is cheap in Algeria. Neither cigars, cigarettes nor pipe mixtures, nor snuff either, pay any excise duties; and even foreign tobaccos, which mostly come from Hungary and the Turkish provinces, pay very little.

Two-thirds of the Algerian manufactured product is made from home-grown tobacco, and a very large quantity of the same is sent to France to be sold as “Maryland;” though, indeed, if the original plants ever came from the other side of the water, it was by a very roundabout route. Certainly the broom-corn tobacco of France does not resemble that of Maryland in the least. The hope of France and her colonies is to grow all the tobacco consumed within her frontiers, whether it is labelled “Maryland,” “Turkish” or “Scaferlati.” The French government puts out some awful stuff it calls tobacco and sells under fancy names.

The tobacco tax in Algeria is nil, and that on wine is nearly so. Four sous a hectolitre (100 litres) is not a heavy tax to pay, though when it was first applied (in 1907) it was the excuse for the retail wine dealer (who in Algeria is but human, when he seeks to make what profit he can) to add two sous to the price of his wine per litre. There is a law in France against unfair trading, and the same applies to Algeria. It has been a dead law in many places for many years, but when a tax of four sous a hectolitre, originally paid to the state, by the dealer, finally came out of the consumer’s pocket as ten francs, an increase of 5,000 per cent., popular clamour and threats of the law caused the dealer to drop back to his original price. This is the way Algeria protects its growing wine industry. Publicists and economists elsewhere should study the system.

The African landscape is very simple and very expressive, severe but not sad, lively but not gay. The great level horizon bars the way south towards the wastes of the Sahara, and the mountains of the Atlas are ever present nearer at hand. The desert of romance, le vrai désert, is still a long way off; and, though there is now a macadamized road to Bou-Saada and Biskra, and a railway to Figuig and beyond, civilization is still only at the vestibule of the Sahara. The real development and exploitation of North Africa and its peoples and riches is yet to come.

As for the climate, that of California is undoubtedly superior to that of Algeria, but the topographical and agricultural characteristics are much the same. The greatest difference which will be remarked by an American crossing Algeria from Oran to Souk-Ahras will be the distinct “foreign note” of the installation of its farming communities. Haystacks are plastered over with mud; carts are drawn by mules or horses hitched tandemwise, three, four or five on end, and the carts are mostly two-wheeled at that. There are no fences and no great barns for stocking fodder or sheltering cattle; the farmhouses are all of stone, bare or stucco-covered, and range in colour from sky-blue to pale pink and vivid yellow. There is some American farming machinery in use, but the Arab son of the soil still largely works with the implements of Biblical times.

The winter of Algeria is the winter of Syria, of Japan, and reminiscent to some extent of California; perhaps not so mild on the whole, but still something of an approach thereto. Another contrast favourable to California is that in Algeria there is a lack of certain refinements of modern travel which are to be had in the “land of sunshine.” Winter, properly speaking, does not come to Algeria except on the high plateaux of the provinces of Oran, Alger and Constantine, and on the mountain peaks of the Atlas, and in Kabylie.

South of Algiers stretches the great plain of the Mitidja, which is like no other part of the earth’s surface so much as it is like Normandy with respect to its prairies, “la Beauce” for its wheat-fields and its grazing-grounds, and the Bordelais for its vineyards.

At the western extremity of the Mitidja commence the orange-groves of Blida, the forests of olive-trees, and the eucalyptus of La Trappe. The scene is immensely varied and suggestive of untold wealth and prosperity at every kilometre.

Suburban Algiers is thickly built with villas, more or less after the Moorish style, but owned by Europeans. Recently the wealthy Arab has taken to building his “country house” on similar gracious lines; and, when he does, he keeps pretty near to accepted Moorish elements and details, whereas the European, the colon, or the commerçant grown rich, carries out his idea on the Meudon or St. Cloud plan. The Moorish part is all there, but the thing often doesn’t hang together.

To the eastward back of the mountains of Kabylie lies the great plateau region of the Tell.

The Tell is a region vastly different in manners and customs from either the desert or the Algerian littoral. The manners of the nomad of the Sahara here blend into those of the farming peasant; but, by the time Batna is reached, they become tainted with the commercialism of the outside world. At Constantine there is much European influence at work, and at the seacoast towns of Bona or Philippeville the Oriental perfume of the date-palm is lost in that of the smells and cosmopolitanism usually associated with great seaports. These four distinct characteristics mark four distinct regions of the Numidia of the ancients, to-day the wheat-growing region of the Tell.

The principal mountain peaks in Algeria rise to no great heights. Touabet, near Tlemcen, is 1,620 metres in height; the highest peak of the Grand Kabylie Range, in the province of Alger, is 2,308 metres; and Chelia, in Constantine, 2,328 metres. They are not bold, rugged mountains, but rolling, rounded crests, often destitute of verdure to the point of desolation.

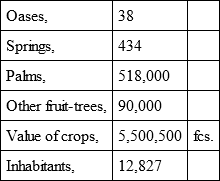

The development of the regions forming the hinterland– practically one may so call the Sahara – is of constant and assiduous care to the authorities. They have done much and are doing much more as statistics indicate.

In the valley of the Oued-Righ and the Ziban, one of the most favoured of these borderlands, the government statistics of springs and oases are as follows (1880-90): —

And as the population increases and fruit-growing areas are further developed, the military engineers come along and dig more wells.

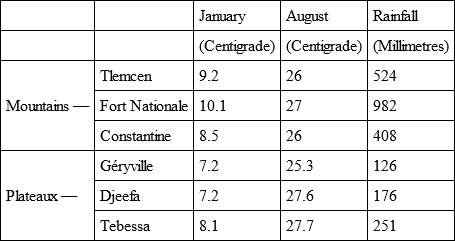

The following average temperatures and rainfall show the contrast between various regions: —

It will be noted that, normally, there is very little difference in temperature, and a very considerable difference in rainfall.

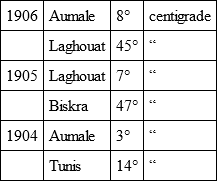

The extreme recorded winter temperatures are as follows: —

Algeria has something like 3,100 kilometres of standard gauge railway, and various light railways, or narrow gauge roads, of from ten to fifty kilometres in length, aggregating perhaps five hundred kilometres more. Railway building and development is going on constantly, but they don’t yet know what an express train is, and the sleeping and dining car services are almost as bad as they are in England. The real up-to-date sleeping-car has electric lights and hot and cold water as well as steam heat. They have dreamed of none of these things yet in England or Africa.

The railway is the chief civilizing developer of a country. The railway receipts in Algeria in 1870 were 2,500,000 francs. In 1900 they were 26,000,000 francs. That’s an increase of a thousand per cent., and it all came out of the country.

The “Routes Nationales” of Algeria (not counting by-roads, etc.), the real arteries of the life-blood of the country, at the same periods numbered almost an equal extent, and they are still being built. Give a new country good roads and good railways and it is bound to prosper.

Four millions of the total population of Algeria (including something over two hundred thousand Europeans) are dependent upon agriculture for their livelihood. Wheat, wine and tobacco rank in importance in the order named.

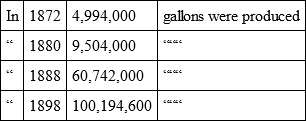

The growth of the wine industry has been most remarkable.

None of it is sold as Bordeaux or Burgundy, at least not by the Algerian grower or dealer. It is quite good enough to sell on its own merits. Let Australia, then, fabricate so-called “Burgundy” and Germany “Champagne” – Algeria has no need for any of these wiles.

Grapes, figs and plums are seemingly better in Algeria than elsewhere. Not better, perhaps, but they are so abundant that one eats only of the best. The rest are exported to England and Germany. The little mandarin oranges from Blida and about there, are one of the stand-bys of Algerian trade. So are olives and dates.

CHAPTER IV

THE RÉGENCE OF TUNISIA AND THE TUNISIANS

FOR twenty years France has been putting forth her best efforts and energies into the development of Tunisia, to make it a worthy and helpful sister to Algeria. From a French population of seven hundred at the time of the occupation in 1882, the number has risen to fifty thousand.

Tunisia of to-day was the Lybia of the ancients; but whether it was peopled originally from Spain, from Egypt or from peoples from the south, history is silent, or at least is not convincingly loud-voiced.

Lybian, Punic, Roman, Vandal and Byzantine, the country became in turn, then Mussulman; for the native Tunisian has not yet become French. The Bey still reigns, though with a shorn fragment of his former powers. The Bey is still the titular head of his Régence, but the French Résident Général is really the premier fonctionnaire, as also he is the Bey’s Ministère des Affaires Étrangères.

The ancient governmental organization of the Bey has been retained with respect to interior affairs. The Caïds are the local governors or administrators of the territorial divisions and are appointed by the Bey himself. They are charged with the policing of their districts, the collecting of taxes, and are vested with a certain military authority with which to impress their tribes. Associated with the Caïds, as seconds in command, are a class called Khalifas, and as tax collectors, mere civil authorities, there are finally the Sheiks.

It was a bitter pill for Italy when France took the ascendancy in Tunis. The population of the city of Tunis to-day still figures 30,000 Italians and Maltese as against 10,000 French, – and ever have the French anti-expansionists called it a “chinoiserie.” Call it what you will, Tunis, in spite of its preponderant Italian influence, is fast becoming French. It is also becoming prosperous, which is the chief end of man’s existence. This proves France’s intervention to have been a good thing, in spite of the fact that it accounts for seventy-five per cent. of the Italian’s animosity towards his Gallic sister.

The death of S. A. Saddok-Bey in 1882, by which the Tunisian sovereign became subservient to the French Resident, was an event which caused some apprehension in France.

The new ruler, Si-Ali-Bey, embraced gladly the French suzerainty in his land that his sons might see the institutions of the Régence prosper under the benign guidance of a world power. Ali-Bey resisted nothing French, – even as a Prince, – and when he came to the Beylicale throne in 1882 he gave no thought whatever to the ultimate political independence of his country. He was ever, until his death, the faithful, liberal coöperator with the succession of Résidents Généreaux who superseded him in the control of the real destinies of Tunisia.

As a sovereign he formerly stood as the absolute ruler of a million souls, not only their political ruler, but their religious head as well. The latter title still belongs to the Bey. (The present ruler, Mohammed-en-Nacer-Bey, came into power upon the death of his predecessor, Mohammed-el-Hadi-Bey in 1906.)

French political administration has robbed the power of the Bey of many of its picturesque and romantic accessories; but the usages of Islam are tolerated not only in the entourage of the Bey, but in all his subjects as well. This toleration even grants them the sanctity of their mosques, and does not allow the hordes of Christian tourists, who now make a playground of Mediterranean Africa from Cairo to Fez, to desecrate them by writing their names in Mohammedan sacred places. In other words, Europeans are forbidden to enter any of the Tunisian mosques save those at Kairouan.

It was Ali-Bey who achieved the task of making the masses understand that their duty was to obey the new régime; that it was a law common to them all that would assure the prosperity of the nation; and that it was he, the Bey, who was still the titular head of their religion, which, after all, is the Mussulman’s chief concern in life.

Might makes right, often enough in a maladroit fashion, but sometimes it comes as a real blessing. This was the case with the coming of the French to Tunisia. A highly organized army was a necessity for Tunisia, and within the last quarter of a century she has got it. The French were far-seeing enough to anticipate the probable eventuality which might grow out of England’s side-long glances towards Bizerte, and the Italian sphere of influence in Tripoli. Now those fears, not by any means imaginary ones at the time, are dead. England must be content with Gibraltar, and Italy with Sardinia. There are no more Mediterranean worlds to conquer, or there will not be after France absorbs Tripoli in Barbary, and Morocco, and the mortgages are maturing fast.

To-day the Tunisians are taxed less than they ever were before, and are better policed, protected and cared for in every way. Their millennium seems to have arrived. France, with the coöperation of the Bey, dispenses the law and the prophets after the patriarchal manner which Saint Louis inaugurated at Carthage in the thirteenth century.

The justice of Ali-Bey and Mohammed-el-Hadi-Bey was an improvement over that of their predecessors, which was tyrannical to an extreme. The Spartan or Druidical under-the-oak justice, and worse, gave way to a formal recognized code of laws which the French authorities evolved from the heritage of the Koran, and very well indeed it has worked.

The Bey had become a veritable father of his people, and was accessible to all who had business with him, meriting and receiving the true veneration of all the Tunisian population of Turks, Jews and Arabs. He interpreted the laws of Mahomet with liberality to all, and from his palace of La Marsa dispensed an incalculable charity.

The present Bey is not an old and tried law-maker or soldier like his predecessors, and beyond a few simple phrases is not even conversant with the French language. He is a Mussulman in toto, but his régime seems to run smoothly, and day by day the country of his forefathers prospers and its people grow fat. Some day an even greater prosperity is due to come to Tunisia, and then the Beylicale incumbent will be covered with further glories, if not further powers. This will come when the great trade-route from the Mediterranean to the heart of Africa, to Lake Tchad, is opened through the Sud-Tunisien and Tripoli, which will be long before the African interior railway dreamed of by the late Cecil Rhodes comes into being.

French influence in Africa will then receive a commercial expansion that is its due, and another Islamic land will come unconsciously under the sway of Christian civilization.

The obsequies of the late Bey of Tunis were an impressive and unusual ceremony. The eve before, the prince who was to reign henceforth received the proclamation of his powers at the Bardo, when he was invested with the Beylicale honours by the authorities of France and Tunisia.

The funeral of the dead Bey was more pompous than any other of his predecessors. He died at his palace at La Marsa and lay in state for a time in his own particular “Holy City,” Kassar-Saïd, on the route to Bizerte, where were present all his immediate family. Prince Mohammed-en-Nacer, the Bey to be, was so overcome with a crisis of nerves that he fell swooning at the ceremony, with difficulty pulling himself together sufficiently to proceed.

The progress of the cortége towards Tunis, the capital, was through the lined-up ranks of fifty thousand Mussulmans lying prostrate on the ground. Entrance to the city was by the Sidi-Abdallah Gate, and thence to the Kasba. The Mussulman population crowded the roof-tops and towers of the entire city. The military guard of the Zouaves, the Chasseurs d’Afrique, and the Beylicale cavalry formed a contrasting lively note to the solemnity of the religious proceedings, though nothing could drown the fervent wails and shouts of “La illah allah, Mohammed Rassone Allah! Sidi Ali-Bey!” the Arabic substitute for “The King is dead! Long live the King!”

Before the Grande Mosquée the Unans-Muftis and the Bach-Muftis recited their special prayers, and all the dignitaries of the new court came to kiss the hand of the reigning prince, who, at the Gate of Dar-el-Bey, was saluted by the Résident Général of France.

The Tomb of the Beys, the Tourbet et Bey, is the sepulchre of all the princes of the house, each being buried in a separate marble sarcophagus, but practically in a common grave.

A fanatical expression which was not countenanced, but which frequently came to pass nevertheless, was the crawling beneath the litter on which reposed the remains of the defunct Bey by numerous Mussulman devotees. The necromancy of it all is to the effect that he who should pass beneath the body of a dead Mussulman ruler would attain pardon for any faults ever afterwards committed. Seemingly it occurred to the authorities that it was putting a premium on crime, and so it was suppressed, and rightly enough.

The political status of the native of Tunisia to-day is similar to that of his brother of Algeria. It is incontestable that the Tunisian’s status under Beylicale rule was not wholly comfortable, for the indigènes were ruled in a manner little short of tyrannical; but the Arab lived always in expectation of bettering his position, in spite of being either a serf or a ground-down menial. To-day he has only the state of the ordinary French citizen to look forward to, and has no hope of becoming a tyrant himself. This is his chief grievance as seen by an outsider, though indeed when you discuss the matter with him he has a long line of complaints to enumerate.

Things have greatly improved in Tunisia since the French came into control. Formerly the native, or the outlander, had no appeal from the Beylicale rule short of being hanged if he didn’t like his original sentence. To-day, with a mixed tribunal of Tunisian and French officials, he has a far easier time of it even though he be a delinquent. He gets his deserts, but no vituperative punishments.

One thing the Tunisian Arab may not do under French rule. He may not leave the Régence, even though he objects to living there. The French forbid this. They keep the indigènes at home for their country’s good, instead of sending them away. It keeps a good balance of things anyway, and the law of the Koran as interpreted by the powers of Tunis is as good for the control of a subject people as that of the Code Napoleon.

The Tunisians, the common people of Tunis, are protégés of France, and France is doing her best to protect them and lead them to prosperity, assisted of course by the good-will and influence of the ruling Bey, whom she keeps in luxury and quasi-power.

Formerly when the native ruler did not care to be bothered with any particular class of subjects, whether they were Turks or Jews, he banished them, but the French officials consider this a superfluous prodigality, and keep all ranks at home and as contented as possible in their work of developing their country.

The one thing that the French will not have is a wholesale immigration of the Arab population of either Algeria or Tunisia. To benefit by a change of air, the indigène of whatever rank must have a special permission from the government before he will be allowed to embark on board ship, or he will have to become a stowaway. Very many get this special permission, for one reason or another, but to many it is refused, and for good and sufficient reasons. To the merchant who would develop a commerce in the wheat of the plateau-lands, the barley of the Sahel, or the dates of the oasis, permission is granted readily enough; and to the young student who would study law or medicine at Aix, Montpellier or Paris; but not to the able-bodied cultivator of the fields. He is wanted at home to grow up with the country.

Tunis la ville and Tunisia le pays are more mediæval and more Oriental than Algiers or Algeria. In Tunis, as in every Arab town, as in Constantinople or Cairo, you may yet walk the streets feeling all the oppression of that silence which “follows you still,” and of a patient, lack-lustre stare, still regarding you as “an unaccountable, uncomfortable work of God, that may have been sent for some good purpose – to be revealed hereafter.”

The morality and the methods of the traders of the bazars and souks remain as Kinglake and Burton described them in their day, something not yet understood by the ordinary Occidental.