полная версия

полная версияIn the Land of Mosques & Minarets

This was only gossip, of course, but it was a sign of the times.

The population of Tunis is the most interesting of all nations under the sun, particularly of a spring or autumn evening as it sits on the broad terrace of one of the boulevard cafés, well dressed and gay, and the Arab the gayest of them all. The Arab of Tunis, when he arrives to a certain distinction, dresses in robes of silk, and silk stockings, too, which he holds up over his bare calves with a “Boston garter,” or a very good imitation thereof. Certainly an Arab whose burnous, haïk, gandurah, caftan, socks, and garters are silk must be a “personage.”

A curious thing to be remarked in the cafés of Tunis is the avidity with which the exiled French population devours the Paris papers upon the arrival of the mail-boat. Another curious thing is the fact that the newsboys sell them in twos and threes; there not being a mail every day, they arrive in bunches of two, three, and sometimes four. One glances at the last one first, but reads it last, at least most people do it that way. It’s human nature.

Throughout Tunis’ Arab quarter the wide-spread hand of Fatmah as a sign of good luck is seen everywhere. It may be stencilled on some shop window, painted over the chimney in a Moorish café, or even stained upon the flank of a horse or donkey. The main de Fatmah is the “good-luck” charm of the Arab, and, as a souvenir to be carried away by the stranger, in the form of a bangle or watch-charm, is about the most satisfactory and characteristic thing that can be had.

After the souks, the palaces and mosques are of chief interest to the traveller. One may not enter the mosques – the French authorities hold the temple of the Mussulman’s God inviolate; but the Dar el Bey and the Bardo, the chief administrative buildings of the native government, may be checked off the indefatigable tourist’s list of “things to see;” as have been Bunker Hill Monument, the Paris Morgue, and Ellen Terry’s cottage at Winchelsea, for presumably these have been “done” first. Such is the craze for seeing sights without knowing what they all mean. “Is it old?” “Does the King, Prince, Bey, or Sultan really live there?” “And are the blood-spots real?” are fair representatives of the class of information which most conventional tourists demand.

The great gates of the inner Arab city of Tunis are most fascinating, with their swarming hordes of passers-by and their grim battlemented walls and towers. The new boulevarded streets circle the old town, and an electric tramway runs in either direction from the Port de France back again to the Port de France. Outside, all is twentieth-century; within, all is a couple of hundred years behind the times at least.

High up above all, behind the Dar el Bey and overlooking the roof-tops of the souks and the town below, is the Kasba and the quaintly decorated minaret of its mosque, the oldest in Tunis, and quite the finest of all the decorative minarets of the world of Islam.

Other mosque minarets at Tunis are svelt and beautiful, dainty and more or less ornate, but they lack the massive luxuriance of that of the Kasba, which was the work, be it recalled, of Italian infidels, not of Mussulman faithful.

Within the charmed circle of the outer boulevards Tunis’ Arab town has an appearance as archaic as one may expect to find in these progressive days. Veiled women are everywhere, and turbaned; high-coiffed, fat, wobbly Jewesses, and Sicilians and Maltese with poignards in their belts. It’s a mixed crew indeed that makes up the life and movement of Tunis. This impression is heightened still further when you see the Bey drive by in state in a dingy carriage drawn by six black, silver-harnessed mules, the outriders yelling, “Arri! Arri! Arri!” like the donkey-boys of the more plebeian world. This sight is followed in the twinkling of an eye by a caravan of camels and nomads of the desert; then perhaps a couple of gaily painted Sicilian carts; an automobile of a very early vintage; another more modern (the dernier cri, in fact), and finally a troop of little bourriquets, grain-laden, making their way westward into the open country. This moving panorama, or another as varied, will pass you inside half an hour as you sit on the terrace of the café opposite the Residency.

At Bab Souika, just without the Arab town, and passed by the tram en route for the Kasba, is the centre of the popular animation of native life. In the Halfaouine quarter are the Moorish cafés, at Bab Djedid still another aspect of Arab loafing and idling, and all of it picturesque to the extreme.

The Jewish dancers of the cafés of the Place Sidi-Baian are recommended as “sights to be seen” by Baedeker and Jouanne. These dancers have eyes like merlans frits, and the ventre doré, and are of the same variety that one has become accustomed to on the “Midway” and the “Pike,” and in the “Streets of Cairo,” which have made the rounds of recent expositions. They are no better nor no worse. The only difference is that here at Biskra, at Constantine, and at Tunis one sees things on their native heath.

Everything in the way of a ceremonial at Tunis centres around the Bey and the Resident-General. The Bey gives a function at the Bardo or at his palace at La Marsa, and the Governor-General attends. The Resident-General has a reception at the Residency, and the Bey drives up behind his six black mules, and, with the first interpreter of his palace, goes in and pays his respects to the representative of Republican France, the real ruler of the “Régence.” “Bon jour” – “Au revoir,” is about the extent of the conversation expected at such functions, and with these simple words said, the ceremony is over. But it is impressive while it lasts, with much gold lace, much bowing and scraping, much music and much helter-skeltering of the entourage here, there, and everywhere.

Republican France still holds out for ceremony, and the President’s “Chasse Nationale” each year at Rambouillet is still reminiscent of “La Chasse Royale” of other days. Not so our bear-hunts in Louisiana cane-breaks. The Bey of Tunis is still the titular head of his people and their religion, but the hand that rules the destiny of his Régence is that of the representative of the French Republic.

CHAPTER XXIII

IN THE SHADOW OF THE MOSQUE

OLD Tunis fortunately remains old Tunis. It has not been spoiled, as has Algiers, in a way. Its crooked streets and culs-de-sac are still as they were when pachas kept their harems well filled as a matter of right, and not by the toleration of the French government.

Surrounding the vast spider’s web of narrow streets of old Tunis is a circling line of tramway, within which is as Oriental an aspect as that of old (save the electric lights and the American sewing-machines, which are everywhere). Without this magic circle, all bustles with the cosmopolitan clamour which we fondly designate twentieth-century progress and profess to like: automobiles, phonographs, type-writing machines, railway trains, great hotels, cafés and restaurants, always the same wherever found.

There is quite as much life and movement in the souks of the old town of Tunis as on the boulevards of the European quarter, and it is quite as feverish, but with a difference. The perfume-makers of the Souk des Parfums still pound their leaves and blossoms by hand in a mortar, and the saddle and shoe makers still stitch and embroider by hand the gold-threaded arabesques of their ancestors. You can get all the products of the souks, of the made-in-Belgium variety, which look quite like the real thing, but in fact are but base “Dutch metal,” unworthy of Arab, Turk, or Jew, and only fit for strangers. Here in the souks you must know how to “shop.” In Tunis, more than in any other city along the Mediterranean, one must know how to sift the dross from the fine metal, and only too frequently the dealer himself will not give you the frank counsel that you need.

Just off the Souk des Grains is the “Street of the Pearls.” In this romantically named thoroughfare, and huddled close beneath the squat, mushroom domes of the Mosque of Sidi-Mahrez is a great brass-studded and bolted doorway, closing an entrance between two svelt marble columns, stolen from Carthage long ago by some unscrupulous Turk or Arab. Above is a great Moorish horseshoe arch. This is the sole entrance to a magnificent, typical Oriental establishment, built three hundred years since by some Turkish pacha fled from Constantinople for political reasons and his country’s good.

Not long since the proprietor of this fine old house was “sold out.” He wasn’t exactly a “poor miserable,” but the establishment he was keeping up was not in keeping with the lining of his purse. He was not as his forefathers, who, if they toiled not nor yet did spin, had the good luck to gather riches by some means or other while they lived. Whilst he, on a scant patrimony to which nothing was being added, was going the pace a little too fast.

His creditors called in the bailiff, and the bailiff called in the auctioneer, and the “bel immeuble,” a “vaste bâtiment 30 mètres carrés, avec cour, fontaine et plusieures pièces au rez-de-chaussée, et balcon,” was put up at auction.

There were no takers, it appeared, – at the price. The “knock-down” was thirty thousand francs, and it was worth it, the finest house in the Oriental quarter of Tunis, high and dry and built of marble and tile, and safe-guarded by the pigeons de bonheur, which lodged on the great central dome of the mosque which overhung the roof-top terrace.

French and Italians, and strangers of all nationalities (including some affected Mussulmans as well), were piling themselves story upon story in great apartment houses in the flat, monotonous new town below, laid out on what a quarter of a century ago was a reedy marsh.

Not one of them would consider for a moment the question of taking on this fine establishment for a dwelling all his own. They all had their summer-houses out at Carthage, where they were spoiling the landscape, as well as that magnificent historic site, by erecting villas of questionable taste. For their town dwellings these ambitious folk were one and all bent on living in a flat.

It was in this manner that this fine example of Oriental domicile fell to our friend, the attaché of the Embassy. He, at least, knew a good thing when he saw it, and, though he was a bachelor (and never for a moment thought of setting up a harem in the vast zenana at the rear), he relished with good will the delights of dwelling in marble halls of his own, – particularly such splendid ones.

It was a problem as to what our friend should do, on account of the great size of the many apartments of this Moorish-Arab house; but like the Japanese and the Moors themselves, he did not make the mistake of filling them with trumpery bric-à-brac and saddle-bag furniture.

It was more or less a great undertaking for a young man to whom housekeeping had hitherto been an unknown accomplishment, – this taking of a great house to live in all alone. For days and weeks, as occasion offered, he stalked its marble halls and pictured the “Arabian Nights” over again, and hazarded many soft and sentimental imaginings as to the personalities of the veiled beauties who once made it their home.

Our friend’s first possession was a servant, of the indefinable species called simply a “man servant;” he at any rate could keep the marbles white and the tiles burnished, and the dust from out the crevices of the carved stone vaultings, if there was nothing else to do.

The serving man was readily enough found. He bore the name of Habib, the Algerian, at least that was the translation that he gave in French of its queer Arab characters, though his explanation as to how he came to descend from parents who were born in Kairouan, the Holy City of Tunisia, and still have the suffix of “the Algerian” tacked on at the end, was not very lucid.

Habib was gentle and faithful, but vain and superstitious. To begin with, he was perfectly willing to become a part and parcel of the ménage; but he must take rank as a body-servant (whatever his duties might be), and would not be a mere caretaker or a concierge. For that M’sieu René must have a Moroccan, the chiens fidèles of North African concierges, or he must go without. Sleep in the house Habib would not; the spirits of past dwellers – some of them perhaps wraiths of folk who had been murdered – would rise up in the dark hours and prevent that; of that he was sure. Stranger infidels might not believe in spooks and spirits, but it was a part of Habib’s faith that he should not put himself in a position where they might destroy his rest. Nothing of the kind had ever happened to him up to now, but the fear was always present, and he was minded to take all possible precautions.

Habib ultimately capitulated, and came to “sleeping in.” He made his plans stealthily for taking up his residence under the shadow of the mosque. Though Habib’s belongings were few, his preparations for moving in were elaborate and lengthy.

Habib had not much more than the clothes on his back, – and a silver-headed cane, without which he never walked the streets of the European quarter, day or night. “In the Arab town you were safe,” he said, “but ‘là-bas,’ with all the civilized and cosmopolitan riffraff of a great Mediterranean seaport, one’s life was not worth a piastre without a weapon of defence.”

You must have a license to carry a revolver in Tunis, a permission which the authorities do not readily grant to an Arab; and anyway Habib was afraid of firearms (he was afraid of most everything, as it appeared later, even work), so he resorted to a cane.

With Habib’s clothes on his back, and his cane, arrived a little plush pillow about the size of a pincushion. This was to be his protection against the real, or fancied, evil spirits which he still believed were lurking away between the walls, as indeed they probably had been for centuries. This little plush cushion had been deftly fashioned for him, doubtless, by some veiled Fatmah or Zorah. It may have honestly been thought by its maker, and of course by Habib, to be an effective antidote for the wiles of roving spirits, but certainly no one would ever attribute to it the least virtues as a pillow. The Japanese wooden head-rest were preferable to Habib’s spirit-charmer for wooing Morpheus.

Habib at last had taken the fatal step, he had become a part and parcel of the establishment. To be sure he had not much to do; the new patron, being alone, had furnished only a part of the chambers, apartments, and salons in semi-European fashion, and Habib’s chief duties consisted only in “turning them out” in succession, on consecutive days, and putting them in order again. There is not a great quantity of grime and dirt that ever penetrates beyond the courtyard of an Arab house, and the actual labour of keeping it clean would please the indolent mind of the laziest “maid of all work” that ever lived.

Habib handled the situation as well as might be expected – for a time. Afterwards he fell off a bit. He was faithful, obliging, smiling and sentimental, but he still slept bad o’ nights, or said he did. The powers of his pincushion pillow were evidently negative or neutral so far as the particular spirits which lodged here were concerned.

With his new station in life Habib came to an increased importance, and from a loose white cotton robe or burnous, he came to be the proud possessor of a flowing creation in crimson silk which was the envy of all his acquaintances. Beneath it he wore a yellow embroidered vest, red silk stockings, and yellow boots of Morocco leather, not really boots, nor yet shoes, but a sort of a cross between a shoe and a moccasin, which cost him the extravagant sum of twenty francs, half a month’s pay.

On his head was perched the conventional red Tunisian fez, with an inordinately long tassel dangling down behind, as effective a chasse-mouches as one would want. This was not all. A dollar watch, with a silver-gilt chain and fob of quaint Kabyle workmanship, – worth probably twenty times the value of the watch, – completed his personal adornment.

As an accessory, Habib became the proud possessor of a visiting-card, which, more than all else, was successful in impressing his confrères and the neighbouring shopkeepers with his importance.

They imagined him, doubtless, a sort of seneschal or majordomo of some kingdom in little.

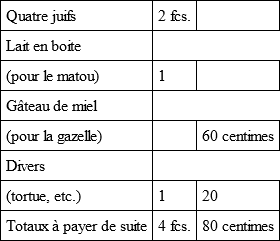

Habib bore his honours lightly and gaily. There was not much fault to be found with him, simply from the fact that he had so little to do that he would be a numskull indeed if he could not, or would not, perform it well. He did perform his duties well, ordinarily, but the first time a good round day’s work fell to his share, such as cleaning down the walls and mopping up the whole area of marbled floor, he rendered an account for the services of “quatre juifs, quarante sous.” Forty cents for the services of four house-cleaners for a day is not dear, and Habib was not even of the same faith as his workmen, so the châtelain paid it gracefully in the next week’s account which Habib rendered.

Habib’s bookkeeping was as original as himself. His accounts for the house-cleaning week read as follows:

How he made both ends meet with the sum total of his modest budget was ever a problem with our friend.

The city-bred Arab has the reputation of being unreliable in money matters, but certainly the hidden graft lying dormant in four francs eighty centimes can not be very great after paying two francs for four Jews, a franc for condensed milk for the cat, sixty centimes for honey-cakes for the gazelle, and a franc twenty centimes for sundry and diverse odds and ends like soap, metal-polish, barley for the turtle, etc. Habib was certainly a good thing!

Habib’s chief pride in the house and its belongings was for the cat, the gazelle, and the turtle, each of them gifts from the same amiable youth. Perhaps he had no place to keep them himself, and in this he saw an opportunity of getting them housed and fed free. Habib may have been wiser than he looked, but at any rate here the menagerie came to be installed as proper and picturesque occupants of this marble palace of other days.

The cat is a useful and even necessary animal in any home, and its virtues have often been praised. A gazelle is purely decorative, but as agreeable and affectionate a little beast as ever lived. The turtle catches flies and lives in a pool of the fountain, and is also useful in keeping down microbes which might otherwise be disseminated. This array of live stock ought to be an adjunct of every house with a fountain courtyard, and if it can be had on the terms as supplied by the faithful Habib, not forgetting the small cost of the animals’ keep, why so much the better.

The particular quarter where our friend’s house was situated was indeed the most quaintly variegated one in all Tunis. At Bab-Souika one turned sharply and entered a veritable labyrinth of narrow, twisting streets, never arriving at the great gate of the house by the same itinerary. Sometimes you arrived directly, and sometimes you circled and tacked like a ship at sea.

From the Place Bab-Souika itself, whence radiated a burning fever of the Arab life of all the ten tribes, it was but the proverbial stone’s throw, by a bird’s-eye view from the roof-top terrace, though by the twisting lanes and alleys it was perhaps a kilometre. There was an occultism and Orientalism here that was to be seen nowhere else in North Africa, and for “mystery” it beat that of the desert, over which poets and novelists rave, all to pieces. No one but an Arab and a Mussulman could ever be a part of that wonderful kaleidoscopic chapter of life. We poor dogs of infidels can only stand by and wonder.

All night long the Place Bab-Souika was as animated as in the day. It was fringed with many Moorish cafés, interspersed with the échoppes of the Tunisian Jews, who push in everywhere, and make a living off of pickings that others think too trivial for their talents. A few boulevard-like trees flank a group of transformed and remodelled Arab houses and give a suspicion of modernity, but the general aspect throughout is Oriental and mediæval. A regular ant-hill of hiving humanity: Moors, Arabs, Turks, Jews, Soudanese, and Touaregs, all with costumes as varied as their origins. Here a creamy-white burnous jostles with a baggy blue pantalon, and the cowled nodding head of a Bedouin rests on the shoulder of an equally somnolent red-fezzed soldier of the Bey. The more wide-awake members of the hangers-on of the cafés enliven the scene with singing and even dancing, perhaps with some Tunisian dancing-girl as a partner. All is gay and scintillating as if it were the most gorgeous café of the Boulevard des Italiens. One and all of the merrymakers are richly costumed, with broidered vests and flowing robes of silk, and clattering silver ornaments and bouquets of flowers, – or a single flower stuck behind the ear, like the Spaniard’s cigarette. All blends into a wonderful fanfare of colour, and it was through this stage-setting our friend had to pass every night as he made his way from the European town below to his Arab house on the height.

The Oriental, when he is making merry at a café, is wholly indifferent to the affairs of the workaday world, if he ever did occupy himself therewith. His point of view is peculiarly his own; we outsiders will never appreciate it, study the question as we may.

Besides the Moorish cafés, the fruit and sweetmeat sellers seem also to do as large a midnight traffic as that of the day. The after-theatre supper of the Arab, if he were given to that sort of thing, would not be difficult of consummation here.

The Arab old-clo’ dealer is another habitué of the neighbourhood. “T’meniach! ra sourdis! T’meniach ’ra T’meniach!” This is the Arab’s old clothes cry. And for a hundred sous, paid over on the Place Bab-Souika, you can be transformed into a Bedouin from head to heel, – with a ragged burnous full of holes and a pair of very-much-down-at-the-heel babouches which have already trod off untold kilometres on the Tunisian highway and are good for many more.

There is another class of ambulant merchant who is a frequenter of this most animated of Tunis’ native quarter. He deals in a better line of goods, in that his wares are new and not second-hand, though tawdry enough, many of them. If you wish you may buy – after appropriate and not to be avoided bargaining, at which you will probably come off second best – a collaret of false sequins, an Arab blanket, or a Turkish ink-pot, which may not be old in spite of its looks. All these things are made to order to-day, after the ancient models and styles, like the cotton goods of India with palm-leaf designs, which are mostly made in Manchester.

“Veux-tu un foulard, Sidi, un beau foulard de Tounis? Vois achète-moi ce poignard Kabyle! Tiens, veux-tu ce bracelet pour madame?” You want none of these things, but you make out as if you did and accordingly you buy “something” before you are through, guiltily thinking you have taken advantage of the poor fellow in that you beat him down from fifteen francs to five for a foulard which cost him, probably, not more than thirty sous of some Israelite “fournisseur” in the souks.

One day Habib the Algerian would work no more. He had succumbed to a bad case of the wandering foot, though what brought it about, save the ennui of his position, – not enough work to do – our friend René never knew. It was doubtful if Habib knew himself. It was as if the termination of Habib’s name had set him to thinking. Habib the Algerian! Why should he not travel a bit, as did these dogs of Christians who were overrunning his beloved land, to Algeria even, he who bore the name of the Algerian, though he had lived since his infancy beneath the shadow of Tunis’ mosques.

“Où vas-tu?” asked his employer, as Habib’s bag and baggage were on the door-sill, a parcel of worldly goods now grown to some proportions, including a nickel alarm-clock, a phonograph, and an oil-stove. American products all of them.