полная версия

полная версияIn the Land of Mosques & Minarets

In spite of its strangeness, Algiers is not at all Oriental. The Arabs of Algiers themselves lack almost totally the aspect of Orientalism. The Turk and Jew have made the North African Arab what he is, and his Orientalism is simply the Orientalism of the East blended and browned with the subtropical rays of the African sun. It is undeniably picturesque and exotic, but it is not the pure Eastern or Byzantine variety which we at first think it. To realize this to the full, one has only to make the comparison between Algiers and Cairo and Tunis.

It is the cosmopolitan blend of the new and the old, of the savage with the civilized, that makes cosmopolitan Algiers what it is. This mixture of many foreign elements of men and manners is greatly to be remarked, and nowhere more than in Algiers’ cafés, where French, English, Americans, and Arabs meet in equality over their café-cognac, though the Arab omits the cognac. The cosmopolitanism of Marseilles is lively and varied, that of Port Saïd ragged and picturesque, but that of Algiers is brilliantly complicated.

Algiers is the best kept, most highly improved, and, by far, the most progressive city on the shores of the great Mediterranean Lake, and this in spite of its contrast of the old and new civilizations. San Francisco could take a lesson from Algiers in many things civic, and the street-cleaners of London and Paris are notably behind their brothers of this African metropolis.

The marchand de cacaoettes is the king of Algiers’ Place du Gouvernement; or, if he isn’t, the bootblack with his “Cire, m’ssieu!” holds the title. Anyway, the peanut-seller is the aristocrat. He sits in the sun with a white or green umbrella over his head, and is content if he sells fifty centimes worth of peanuts a day. His possible purchasers are many, but his clients are few, and at a sou for a fair-sized bag full, he doesn’t gather a fortune very quickly. Still he is content, and that’s the main thing. The bootblack is more difficult to satisfy. He will want to give your shoes a “glace de Paris,” even if another of his compatriots has just given them a first coating of the same thing. The bootblacks of Algiers are obstinate, importunate, and exasperating.

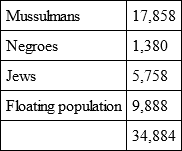

From a document of 1621 one learns that Algiers had a population of 100,000 in 1553, a half a century later 150,000, and in 1621 200,000. Then came the decadence; and, at the coming of the French in 1832, Algiers was but a city of 34,000, Moors, Turks, Jews, Negroes, and Arabs all counted.

They were divided as follows:

By 1847 a European population had crowded in which brought the figures up to 103,610 and gave Algiers a rank of fifth among French cities.

Algiers’ busy port is picturesque and lively in every aspect, with the hourly comings and goings of great steamships from all the length and breadth of the Mediterranean, and from the seven seas as well. Over all is the great boundless blue of a subtropical, cloudless sky; beneath the restless lapping of the waves of the still bluer Mediterranean; and everywhere the indescribable odour of bitume, of sea salt, and of oranges. The background is the dazzling walls of the arcaded terraces of the town, and the still higher turrets and towers of a modern and ancient civilization. Still farther away are the rolling, olive-clad hills and mountains of the Sahel. Sunrise or sunset on Algiers’ port are alike beautiful; one should miss neither.

The best-remembered historical and romantic figures of Algiers are Pedro Navarro, who built the Peñon; the brothers Barberousse, Corsairs from the Dardanelles, whom the Algerians called in to help them fight their battles against Christianity; and Cervantes, the author of “Don Quixote,” who was imprisoned here, and who left an imperishable account of the city of his captivity, ever useful to later historians.

Charles V and Louis XIV both had a go at Algiers, but it fell not to their attack; and it was only with later times, incident upon an insult offered the French ambassador by Hussein Dey, the Turkish ruler of the El-Djezair of the ancients, that Algiers first capitulated to outside attack.

Old Algiers was not impregnable, perhaps, but such weapons of warfare as were used against the Turks were inefficient against its thick walls, its outposts, and its fortified gates.

The historic Peñon underwent many a mediæval siege, but was finally captured from its Spanish defender, De Vegas, and his little band of twenty-five survivors, who were summarily put to death. Khair Ed Din pulled down, in part, the fortifications and joined the remainder by a jetty to the mainland, the same break-water which to-day shelters the port on the north. A fragment of one of the original signal towers was built up into the present lighthouse, and a system of defences, the most formidable on the North African coast, was begun. The fortifications of Algiers were barriers which separated the growing civilization of Europe from the barbarian nether world, and they fell only with the coming of the French in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Such is the story of the entering wedge of progressive civilization in Algeria.

Algiers’ veiled women are one of the city’s chief and most curious sights for the stranger within her walls. On Friday, the jour des morts of the Arab women, they go to the cemetery to weep or to make gay, according as the mood is on. For the recluse Arab women it is more apt to be a fête-day than a day of sorrow. They dress in their finest, their newest, and their cleanest, and load themselves down with jangling jewelry to the limit of their possessions. By twos and threes, seldom alone, they go to make their devotions at the Kouba of Didi-Mohammed Abd-er-Rahman Bou Kobrin.

Poor prisoner women; six days a week they do not put foot outside their doors; and on the seventh they take a day’s outing in the cemetery. “Pas gai!” says the Frenchwoman, and no wonder.

When the sun commences to lower, they quit the cemetery of Bou-Kobrin and file in couples and trios and quartettes back to their homes in the narrow shut-in streets which huddle about the grim walls of the hilltop Kasba. They toddle and crawl and almost creep, as if they feared entering their homes again; they have none of that proud, elastic, jaunty step of the Kabyle women or of the Bedouins of the “Great Tents;” they are only poor unfortunate “Arab women of the walls.”

One after another these white-veiled pyramids of femininity disappear, burrowing down through some low-hung doorway, until finally their weekly outing is at an end and they are all encloistered until another seventh day rolls around.

That these Mauresque women of Algiers are beautiful there is no doubt, but their beauty is of the qualified kind. The chief attribute to the beauty of the Mauresque woman is kohl or kohol or koheul, a marvellous preparation of sulphur, of antimony of copper and of alum – and perhaps other things too numerous to mention, all of which is made into a paste and dotted about all over the face as beauty-spots. Sometimes, too, they kalsomine the face with an enamel, like that on a mediæval vase. Those of the social whirl elsewhere use a similar concoction under another name which is sold by high-class chemists and perfumers, but they don’t let you know what it is made of, or at any rate, don’t take you into their confidence – neither the chemists nor the women.

When a Mauresque dyes herself to the eyes with kohl, and dips her finger-tips in henna until they are juicy red, then she thinks she is about as ravishing as she can be in the eyes of God, her lover, and herself. She has to do this, she thinks, to keep her favour with him, because others might perchance put it on a little thicker and so displace her charms, and his affection.

It is a belief among Mussulman women that Mahomet prescribed the usage of kohl, but this idea is probably born of the desire. Certainly no inspiration of God, nor the words of his prophet, ever suggested such a thing.

CHAPTER XVI

ALGIERS AND BEYOND

TO get into the interior back of Algiers, you make your start from Maison Carrée. Here one gets his first glimpse of the real countryside of Algeria. These visions of the Arab life of olden times are quite the most interesting features of the country. Civilization has crept in and rubbed shoulders very hard here and there; but still the Arab trader, workman, and shopkeeper conducts his affairs much as he did before he carried a dollar watch and lighted his cigarettes with safety matches.

The kaleidoscopic life of the market at Maison Carrée is one of the sights of suburban Algiers. Here on a vast, dusty down, packed everywhere with donkeys, mules and blooded Arabians, and there in a great enclosure containing three or five thousand sheep, is carried on as lively a bit of trading as one will observe anywhere outside a Norman horse-fair or a land sale on some newly opened reservation in the Far West.

Horses, donkeys, mules, and sheep cry out in all the varied accents of their groans and bleatings, the sheep and their lambs, lying with their four feet tied together, complaining the loudest. Hundreds of Arabs, Kabyles, Turks, Jews, and Europeans bustle and rustle about in picturesque disorder, doing nothing apparently, but vociferating and grimacing. All sorts of footwear and head-gear are here, turbans, fezes, haiks, sandals, sabots, and espadrilles. Gay broidered vestments and dirty rent burnouses jostle each other at every step.

Mutton is up or down to-day, a sheep may sell for eight francs or it may sell for twenty, and the buyer or seller is glad or sorry, he laughs, or he weeps, – but he smokes and drinks coffee at all times nevertheless.

In a snug corner are corralled some Arab steers and cows, a rare sight even in the markets of Algiers. One eats mutton all the time and everywhere, but seldom beef. The butchers of Algiers corner it for the milords and millionaires of the Mustapha hotel, who demand “underdone” beefsteaks and “blood-running” roasts of beef for breakfast, dinner, and supper.

An Arabian horse, so-called, but not a blooded beast, sells here for from eighty to two hundred francs. High-priced stock is rare here, hence there is little horse-trading of the swindling variety, and no horse thieving. The Arab maquignons, dressed in half European and half desert fashion, bowler hats and a burnous, sandals and bright blue socks with red clocks on them, are, however, more insistent, if possible, than their brothers of Brittany.

“You want to buy a horse, un chiv’l?” says a greasy-looking blackamoor. “Moi, z’en connaiz-un, 130 francs, mais z’i peux ti l’avoir pour 95.” You don’t want to buy a horse, of course, but you ask its age. “Moi, s’i te sure, neuf ou dix ans peut-être – douze ans, mais ze, ze le connais, il trotte comme la gazelle.” It’s all very vague, including the French, and you get away as soon as you can, glad at any rate that you have lost neither time nor money.

All the trading of the Arab market is, as the French say, pushed to the limit. Merchandizing describes the process, and describes it well. A hundred sous, a pièce only, refused or offered, will make or break a bargain almost on the eve of being concluded.

An Arab trader in – well, everything – has just sold half a ton of coal to a farmer living a dozen kilometres out in the country. The farmer bought it “delivered,” and the Arab coal merchant of the moment bargains with a Camel Sheik for fifty sous to deliver the sooty charge by means of three camels. Three camels, twenty-four kilometres (a day’s journey out and back), and a driver costs fifty sous, two francs and a half, a half a dollar. It’s a better bargain than you could make, and you marvel at it.

A troop of little donkeys comes trotting up the hillside to the market, loaded with grain, dates, peanuts, and some skinny fowls and ducks. They have “dog-trotted” in from Rovigo, thirty kilometres distant, and they will trot back again as lively after breakfast, their owner beating them over the flanks all the way. Poor, patient, clever little beasts, docile, but not willing! Yes, not willing; a donkey is never willing, whatever land he may live in.

Booths and tents line the sides of the great square, filled with the gimcrack novelties of England, France, Germany, and America, – and the more exotic folderols of Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco. Jews sell calico, and Turks and Greeks sell fraudulent gold and silver jewelry and coral beads made of glass melted in a crucible. Merchandise of all sorts and of all values is spread on the bare ground. A pair of boxing gloves, an automobile horn, a sword with a broken blade, and all kinds of trumpery rubbish cast off from another world are here; and before night somebody will be found to buy even the boxing-gloves.

Europeans, too, are stall-holders in this great rag-fair. Spaniards and Maltese are in the greatest proportions, and the only Frenchmen one sees are the strolling gendarmes poking about everywhere.

Noon comes, and everybody with a soul above trade repairs to a restaurant of the middle class near by, a great marble hall fitted with marble top tables. Here every one lunches with a great deal of gesticulation and clamour. It is very primitive, this Algerian quick-lunch, but it is cleanly and the food is good. For twenty-five sous you may have a bouillabaisse, a dish of petits pois, two œufs à la coque, goat’s-milk cheese, some biscuits and fruit for dessert, a half-bottle of wine and café et kirsch. Not so bad, is it?

“The better one knows Algeria,” says the brigadier of gendarmes, or the lieutenant in some army bivouac, “the less one knows the Arab.” The point of view is traditional. The serenity and taciturn manner of the Arab is only to be likened to that of the Celestial Wong Hop or Ah Sin. What the Arab thinks about, and what he is likely to do next no one knows, or can even conjecture with any degree of certainty. All one can do is to jump at conclusions and see what happens – to himself or the Arab.

When the Duc d’Aumale conquered Biskra, the Arabs promptly retook it, practically, if not officially, and gave themselves up to such abandoned orgies that not even the military authorities could make them tractable. The authorities at Paris were at their wits’ ends how to win the hearts of the Arabs, and conquer them morally as well as physically. Louis-Philippe made a shrewd guess and sent Robert Houdin, the prestidigitateur, down into the desert. From that time on the Arab of Algeria has been the tractable servant of the French.

Straight south from Maison Carrée, across the Mitidja, eighteen kilometres more or less, lies Arba, the beginning of the real open country. A steam-tram goes on ten kilometres farther, to Rovigo. At Arba, however, the “Route Nationale” to the desert’s edge branches off via Aumale to Bou-Saada and beyond, where the real desert opens out into the infinite mirage.

The nearest the camel caravans of the desert ever get to Algiers is at this little market town of Arba. Here on a market day (Wednesday) may be seen a few stray, mangy specimens of the type loaded with grapes, figs, or dates, though usually the bourriquet, or donkey, is the beast of burden. The Arab never carries his burdens himself, as do other peasants. It is beneath his dignity; for no matter how ragged or rusty he is, his burnous is sacred from all wear and tear possible to be avoided.

Except for its great market back of its modern ugly mosque, there is not much to see in Arba. Here is even a more heterogeneous native riffraff than one sees at Maison Carrée, Blida, or Boufarik. And indeed it is all “native,” for the Turks and Jews of the coast towns are absent. The trading is all done in produce. And if the native merchant, in his little shop or stall where he sells foreign-made clothes and gimcracks, cannot sell for cash, he is willing to barter for a sack of grain or a few sheep or some goat skins. The Jew trader will not bother with this kind of traffic. He wants to deal for cash, either as buyer or seller, he doesn’t care which.

Here a native shoemaker, or rather maker of babouches, sits beneath a rude shelter and fashions fat, tubby slippers out of dingy skins and sole leather with the fur left on. On another side is a sweetmeat seller, a baker of honey cakes, and a vegetable dealer, and even a butcher, who tries to lead his Mussulman brother astray and get him to become a carnivorous animal like us Christians. He doesn’t succeed very well, because the Arab eats very little meat.

In a tent, beneath a great palm, sits the physician and dentist of the tribe, with all his paraphernalia of philters and potions and tooth-pulling appliances. Like the rest of us, the Arab suffers from toothache sometimes; and he wastes no time but goes and “has it out” at the first opportunity. The procedure of the Arab tooth-puller is no more barbaric than our own, and the possessor of the refractory molar has an equally hard time. All these things and more one sees at Arba’s weekly market. It is all very strange and amusing.

Aumale is nearly a hundred kilometres beyond Arba, with nothing between except occasional settlements of a few score of Europeans and a few hundreds of Arabs. Communication with Algiers from Aumale is by a crazy, rocking seven-horse diligence which covers the ground, by night as often as by day, in nine or ten hours, at a gait of six or seven miles an hour, and at a cost of as many francs.

Aumale is nothing but the administrative centre of a commune blessed with two good enough inns and a long, straight main street running from end to end. As the Auzia of the Romans, it was formerly occupied by a strong garrison. The Turks in turn built a fortress on the same site, and the French occupied it as a military post in 1846, giving it a second baptism in the name of the Duc d’Aumale, the son of Louis-Philippe.

From Aumale on to Bou-Saada is another hundred and twenty-four kilometres over a new-made “Route Nationale.” It is a good enough road for a diligence, which makes the journey in sixteen or eighteen hours, including stops. There is no accommodation en route save that furnished by the government bordjs, the caravanserai and the café-maures.

Here, at last, one is launched into the desert itself. The journey is one of strange, impressive novelty, though nothing very venturesome. In case of a prolonged breakdown, there is nothing to do but to drink the water of the redir (a sort of a natural pool reservoir hollowed out of the rock), and be thankful indeed if your curled-up Arab travelling companion will share his crust with you. To him white bread, if only soaked in water, is a great luxury; to you it will seem pretty slim; but then we are overfed as a rule and an Arab dietary for a time will probably prove beneficial. The life of the nomad Arab is a very full one, but it is not a very active nor luxurious one.

Through wonderful ocean-like mirages and clouds of dust whirled up by the sirocco, a veritable “tourbillon de poussière,” as Madame de Sévigné would have called it, we rolled off the last kilometres of our tiresome journey, just as the last rays of the blood-red sun were paling before the coming night. We arrived at Bou-Saada’s Hotel Bailly just as the last remnants of the table d’hôte were being cleared away, which, in this little border town, half civilized and half savage, means thrown into the streets to furnish food for chickens. How the inhabitant of the Algerian small town ever separates his own fowls from those of his neighbours is a great question, since they all run loose in the common feeding-ground of the open street.

Bou-Saada is even of less importance than Aumale to the average person. But for the artist it is a paradise. It is not Tlemcen, it has no grand mosques; it is not Tunis, it has no great souks and bazaars; but it is quaintly native in every crooked street huddled around the military post and the hotels. The life of the leather and silver workers, and of the butcher, the baker and the seller of blankets and foodstuffs is, as yet, unspoiled and uncontaminated with anything more worldly than oil-lamps. The conducted tourist has not yet reached Bou-Saada, and consequently the native life of the place is all the more real.

Here is an account of a café acquaintance made at Bou-Saada. Zorah-ben-Mohammed was a pretty girl, according to the standards of her people, with a laugh like an houri. She confessed to eighteen years, and it is probable that she owned no more. The rice powder and the maquillage were thick on her cheek, whilst the rest of her face was frankly ochre. For all that she was a pretty girl and came perilously near convincing us of it, though hers was a beauty far removed from our own preconceived standards.

Great black eyes and a massive coiffe of raven-black hair topped off her charms. Below she was clad in a corsage of gold-embroidered velvet and an ample silk pantalon that might indeed have been a skirt, so large and thick were its folds. Bijoux she had galore. They may have been of gold and silver and precious stones, or they may not; but they were precious to her and added not a little to her graces. Bracelets bound her wrists and her ankles, and her finger-tips were dyed red with henna.

Zora or Zorah Fatma, or in Arab, Fetouma, are the girlish names which most please their bearer, and our friend Zorah was a queen in her class. Zorah served the coffee in the little Moorish café in Bou-Saada’s market-place, into which we had tumbled to escape a sudden sandstorm blown in from the desert. Her powers of conversation were not great; she did not know many French words and we still fewer Arab ones, so our respective vocabularies were soon exhausted. We admired her and made remarks upon her, – which was what she wanted, and, though the charge for the coffee was only two sous a cup, she was artful enough to worm a pourboire of fifty centimes apiece out of us for the privilege of being served by her.

As we left, Zorah, with her professional little laugh on her lips, cried out, “redoua, redoua!” (to-morrow, to-morrow!) “Well – perhaps!” we answered. “Peut-être que oui! Peut-être que non!”

A visit to the marabout at El Hamel, fifteen kilometres from Bou-Saada, is one of the things to do. We descended upon him in his hermit shrine, and found him seated on a great carpet of brilliant colouring and reclining on an enormous cushion of embroidered silk, – not the kind the Tunisian workers try to sell steamship-cruising tourists during their day on shore, but the real gold-embroidered, silky stuff, such, as dressed the characters of the Arabian nights.

Hung about the marabout’s neck was his chaplet of little ebony beads, and behind his head hung an embroidered silken square, its gold olive branches and fruit glittering with sun’s rays like an aureole.

Grouped about the marabout in a squatting semicircle and listening to his holy words were a half-dozen or more faithful Mussulmans. One of them was very old, with a visage ridged like a melon rind, and a fringe of beard that once was probably black, but was now a scant gray collaret. His face was the colour of brown earth, but he was manifestly a pure blooded Arab; there was not even the telltale pearly-blue tint in the eyes which always marks the half-bred Berber-Arab type. Another, rolled snug in an old burnous, was by his side, his eyes quite closed and his head and body rocking as though he was asleep. He probably was. A third was younger, of perhaps three and thirty, but he was quite as devout as his elders, though he was more wide-awake, and looked curiously and interestedly upon us as we stood in the doorway of the little white temple of a sanctuary awaiting the time when the marabout should be free of his religious duties.

Our visit was appreciated. We had brought the holy man a few simple gifts of chocolate, matches, and a couple of candles, and donated twenty copper sous to his future support. After the adieux of convention were exchanged, we jogged our little donkeys back to the town by a short cut through the bed of the Oued Bou-Saada.