полная версия

полная версияThe Cathedrals and Churches of the Rhine

The walls of the ancient "ecclesiastical city" enclose a plat nearly triangular in form. On one side are the canons' residences and other domestic establishments, and on the other the cathedral and the bishop's palace.

In the episcopal palace are a number of fine portraits, which are more a record of manners and customs in dress than they are of churchly history.

The small cathedral and all the other edifices date from an eighth-century foundation, and are in the manifest Romanesque style of a very early period.

Within the cathedral are a number of funeral monuments of not much artistic worth and a series of paintings by Holbein and Dürer. As an art centre Coire would appear to rank higher than it does as a city of architectural treasures, for it was also the birthplace of Angelica Kauffmann, who was born here in 1741.

Ragatz is more famous as a "watering-place" – for the baths of Pfeffers are truly celebrated – than as a treasure-house of religious art, though in former days the abbey of Pfeffers was of great renown. Its foundation dates from 720, but the building as it exists to-day was only erected in 1665. The church, in part of marble, contains some good pictures. The abbey was formerly very wealthy, and its abbot bore the title of prince. The convent is to-day occupied by the Benedictines, to whom also the baths belong.

From this point on, as one draws near the Lake of Constance, the Alpine character of the topography somewhat changes.

The Lake of Constance was known to the Romans as Brigantinus Lacus or the Lacus Rheni. It has not so imposing a setting as many of the Swiss or Italian lakes, but its eighteen hundred square kilometres give the city of Constance itself an environment that most inland towns of Europe lack. The Lake of Constance, like all of the Alpine lakes, is subject at times to violent tempests. It is very plentifully supplied with fish, and is famous for its pike, trout, and, above all, its fresh herring.

From Basel the Rhine flows westward under the last heights of the Jura, and turns then to the north beneath the shelter of the Vosges, and, as it flows by Strasburg, first begins to take on that majesty which one usually associates with a great river.

At the confluence of the Main, after passing Speyer, Worms, and Mannheim, the Rhine first acquires that commercialism which has made it so important to the latter-day development of Prussia.

At the juncture of the Main and Rhine is Mayence, one of the strongest military positions in Europe to-day. Here the Rhine hurls itself against the slopes of the Taunus and turns abruptly again to the west, aggrandizing itself at the same time, to a width of from five hundred to seven hundred metres.

Shortly after it has passed the last foot-hills of the Taunus, it enters that narrow gorge which, for a matter of 150 kilometres, has catalogued its name and fame so brilliantly among the stock sights of the globe-trotter.

No consideration of the economic part played by the Rhine should overlook the two international canals which connect that river with France through the Rhône and the Marne.

The first enters the Rhine at Strasburg, a small feeder running to Basel, and the latter, starting at Vitry-le-François, joins the Marne with the Rhine at the same place, Strasburg.

On the frontier of the former département of the Haut-Rhin, one may view an immense horizon from the south to the north. From one particular spot, where the heights of the Vosges begin to level, it is said that one may see the towers of Strasburg, of Speyer, of Worms, and of Heidelberg. If so, it is a wonderful panorama, and it must have been on a similar site that the Château of Trifels (three rocks) was situated, in which Richard Cœur de Lion was imprisoned when delivered up to Henry VI. by Leopold of Austria.

To distract himself he sang the songs taught him by his troubadour, to the accompaniment of the harp, says both history and legend, until one day the faithful Blondel, who was pursuing his way up and down the length of Europe in search of his royal master, appeared before his window.

Some faithful knights, entirely devoted to their prince, had followed in the wake of the troubadour, and were able to rescue Richard by the aid of a young girl, Mathilde by name, who had recognized the songs sung by Blondel as being the same as those of the royal prisoner in the tower of the château. When the troubadour was led to the door of the prince's cell, he heard a voice call to him: "Est-ce toi, mon cher Blondel?" "Oui, c'est moi, mon seigneur," replied the singer. "Comptez sur mon zèle et sur celui de quelques amis fidèles – nous vous deliverons."

The next day the escape was made through an overpowering of the guard; and Richard, in the midst of his faithful chevaliers, ultimately arrived in England.

Blondel had meanwhile led the willing Mathilde to the altar, and received a rich recompense from the king.

As the Rhine enters the plain at Cologne, it comes into its fourth and last phase.

Flowing past Düsseldorf and Wesel, it quits German soil just beyond Emmerich, and enters the Low Countries in two branches. The Waal continues its course toward the west by Nymegen, and through its vast estuary, by Dordrecht, to the sea.

The Rhine proper takes a more northerly course, and, as the Neder Rijn, passes Arnheim and Utrecht, and thence, taking the name of Oud Rijn, fills the canals of Leyden and goes onward to the German Ocean.

Twelve kilometres from Leyden is Katwyck aan Zee, where, between colossal dikes, the Rhine at last finds its way to the open sea. More humble yet at its tomb than in the cradle of its birth, it enters the tempestuous waters of the German Ocean through an uncompromising and unbeautiful sluice built by the government of Louis Bonaparte.

For more than eleven hundred kilometres it flows between banks redolent of history and legend to so great an extent that it is but natural that the art and architecture of its environment should have been some unique type which, lending its influence to the border countries, left its impress throughout an area which can hardly be restricted by the river's banks themselves.

We know how, in Germany, it gave birth to a variety of ecclesiastical architecture which is recognized by the world as a distinct Rhenish type. In Holland the architectural forms partook of a much more simple or primitive character; but they, too, are distinctly Rhenish; at least, they have not the refulgence of the full-blown Gothic of France.

Taine, in his "Art in the Netherlands," goes into the character of the land, and the struggle demanded of the people to reclaim it from the sea, and the energy, the vigilance required to secure it from its onslaughts so that they, for themselves and their families, might possess a safe and quiet hearthstone. He draws a picture of the homes thus safeguarded, and of how this sense of immunity fostered finally a life of material comfort and enjoyment.

All this had an effect upon local architectural types, and the great part played by the valley of the Rhine in the development of manners and customs is not excelled by any other topographical feature in Europe, if it is even equalled.

Coupled to the wonders of art are the wonders of nature, and the Rhine is bountifully blessed with the latter as well.

The conventional Rhine tour of our forefathers is taken, even to-day, by countless thousands to whom its beauties, its legends, and its history appeal. But whether one goes to study churches, for a mere holiday, or as a pleasant way of crossing Europe, he will be struck by the astonishing similarity of tone in the whole colour-scheme of the Rhine.

The key-note is the same whether he follows it up from its juncture with salt water at Katwyck or through the gateway of the "lazy Scheldt," via Antwerp, or through Aix-la-Chapelle and Cologne.

Sooner or later the true Rhineland is reached, and the pilgrim, on his way, whether his shrines be religious ones or worldly, will drink his fill of sensations which are as new and different from those which will be met with in France, Italy, and Spain as it is possible to conceive.

From the days of Charlemagne, and even before, down through the fervent period of the Crusades, to the romantic middle ages, the Rhine rings its true note in the gamut, and rings it loudly. It has played a great part in history, and to its geographical and political importance is added the always potent charm of natural beauty.

The church-builder and his followers, too, were important factors in it all, for one of the glories of all modern European nations will ever be their churches and the memories of their churchmen of the past.

III

THE CHURCH IN GERMANY

There have been those who have claimed that the two great blessings bestowed upon the world by Germany are the invention of printing by Gutenberg, which emanated from Mayence in 1436, and the Reformation started by Luther at Wittenberg in 1517. The statement may be open to criticism, but it is hazarded nevertheless. As to how really religious the Germans have always been, one has but to recall Schiller's "Song of the Bell." Certainly a people who lay such stress upon opening the common every-day life with prayer must always have been devoted to religion.

The question of the religious tenets of Germany is studiously avoided in this book, as far as making comparisons between the Catholic and Protestant religions is concerned.

At the finish of the "Thirty Years' War," North Germany had become almost entirely Protestant, and many of the former bishops' churches had become by force of circumstances colder and less attractive than formerly, even though many of the Lutheran churches to-day keep up some semblance of high ceremony and altar decorations. It is curious, however, that many of these churches are quite closed to the public on any day but Sunday or some of the great holidays.

In the Rhine provinces the Catholic faith has most strongly endured. In the German Catholic cathedrals the morning service from half-past nine to ten is usually a service of much impressiveness, and at Cologne, beloved of all stranger tourists, nones, vespers, and compline are sung daily with much devotion.

The ecclesiastical foundation in Germany is properly attributable to monkish influences. Between the Rhine and the Baltic there were no cities before the time of Charlemagne, although the settlements established there by the Church for the conversion of the natives were the origin of the communities from which sprang the great cities of later years.

The monkish orders were ever a powerful body of church-builders, and north of the Alps in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, even though they were the guardians of literature as well as of the arts, the monks were possessed of an energy which took its most active form in church-building.

Whatever may have been the origin of the later Romanesque church-building, whether it was indigenous to Lombard Italy or not, it was much the same in Spain, France, England, and Germany, though it took its most hardy form in Germany, perhaps with the cathedral of Speyer (1165-90), which is one of the latest Romanesque structures, contemporary with the early Gothic of France. In Italy, and elsewhere along the Mediterranean, the pure Romanesque was somewhat diluted by the Byzantine influence; but northward, along the course of the Rhine, the Romanesque influence had come to its own in a purer form than it had in Italy itself.

Here it may be well to mention one pertinent fact of German history, in an attempt to show how, at one time at least, Church and state in Germany were more firmly bound together than at present.

The Germanic Empire, founded by Charlemagne in the year 800, was dissolved under Francis II., who, in 1806, exchanged the title of Emperor of Germany for that of Emperor of Austria, confining himself to his hereditary dominions.

In the olden times the Germanic Empire was in reality a league of barons, counts, and dukes, who, through seven of their number, elected the emperor.

These electors were the Archbishops of Mayence (who was also Primate and Archchancellor of the Empire), Trèves, and Cologne; the Palatine of the Rhine, Arch-Steward of the Empire; the Margrave of Brandenburg, Arch-Chamberlain; the Duke of Saxony, Arch-Marshal; and the King of Bohemia, Arch-Cupbearer.

In no part of the Christian world did the clergy possess greater endowments of power and wealth than did those of the Rhine valley.

The Archbishop of Cologne was the Archchancellor of the Empire, the second in rank of the electoral princes, and ruler of an immense territory extending from Cologne to Aix-la-Chapelle; while the Archbishops of Mayence and Trèves played the rôle of patriarchs, and were frequently more powerful even than the Popes.

All the bishops, indeed, were invested with rights both spiritual and temporal, those of the churchman and those of the grand seigneur, which they exercised to the utmost throughout their dioceses.

St. Boniface was sent on his mission to Germany in 715, having credentials and instructions from Pope Gregory II. He was accompanied by a large following of monks versed in the art of building, and of lay brethren who were also architects. This we learn from the letters of Pope Gregory and the "Life of St. Boniface," so the fact is established that church-building in Germany, if not actually begun by St. Boniface, was at least healthily and enthusiastically stimulated by him.

Among the bishoprics founded by Boniface were those of Cologne, Worms, and Speyer, and it may be remarked that all of these cities have ample evidences of the round-arched style which came prior to the Gothic, which followed later. If anything at all is proved with regard to the distinct type known as Rhenish architecture, it is that the Lombard builders preceded by a long time the Gothic builders.

Charlemagne's first efforts after subduing the heathen Saxons was to encourage their conversion to Christianity. For this purpose he created many bishoprics, one being at Paderborn, in 795, a favourite place of residence with the emperor.

Great dignity was enjoyed by the Bishop of Paderborn, certain rights of his extending so far as the Councils of Utrecht, Liège, and Münster. The abbess of the monastery at Essen, near Düsseldorf, was under his rule; and the Counts of Oldenberg and the Dukes of Clèves owed to him a certain allegiance; while certain rights were granted him by the cities of Cologne, Verdun, Aix-la-Chapelle, and others.

These dignities endured, in part, until the aftermath of the French Revolution, which was the real cause of the disrupture of many Charlemagnian traditions.

After the Peace of Lunéville, in 1801, the electorates of Cologne, Trèves, and Mayence were suppressed, together with the principalities of Münster, Hildesheim, Paderborn, and Osnabrück, while such abbeys and monasteries as had come through the Reformation were dissolved.

Besides Charlemagne's bishoprics, others founded by Otho the Great were suppressed.

Upon the restoration of the Rhenish provinces to Germany in 1814, the Catholic hierarchy was reëstablished and a rearrangement of dioceses took place. A treaty with the Prussian state gave Cologne again an archbishopric, with suffragans at Trèves, Münster, and Paderborn, and Count Charles Spiegel zum Desenburg was made archbishop. Other provinces aspired to similar concessions, and certain of the suppressed sees were reërected.

The Lutherized districts, north and eastward of the Rhine, were very extensive, but the influence which went forth again from Cologne served to counteract this to a great extent.

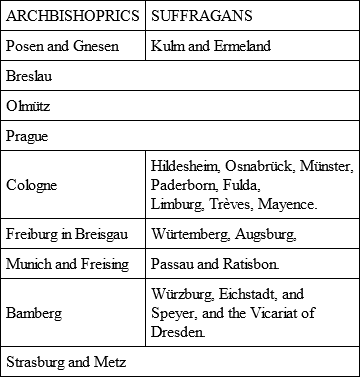

The Catholic hierarchy in Germany is made up as follows:

The religious population of Germany to-day is divided approximately thus: Protestants, 63 per cent; Catholics, 36 per cent; Jews, 1 per cent.

The reign of the pure Gothic spirit in church-building, as far as it ever advanced in Germany, was at an end with the wars of the Hussites and the Reformation of Luther. During these religious and political convulsions, the Gothic spirit may be said to have died, so far as the undertaking of any new or great work goes.

Just as we find in Germany a different speech and a different manner of living from that of either Rome or Gaul, we find also in Germany, or rather in the Rhenish provinces, a marked difference in ecclesiastical art from either of the types which were developing contemporaneously in the neighbouring countries.

The Rhine proved itself a veritable borderland, which neither kept to the strict classicism of the Romanesque manner of building, nor yet adopted, without question, the newly arisen Gothic of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Architecture and sculpture in its earliest and most approved ecclesiastical forms undoubtedly made its way from Italy to France, Spain, Germany, and England, along the natural travel routes over which came the Roman invaders, conquerors, or civilizers – or whatever we please to think them.

Under each and every environment it developed, as it were, a new style, the flat roofs and low arches giving way for the most part to more lofty and steeper-angled gables and openings. This may have been caused by climatic influences, or it may not; at any rate, church-building – and other building as well – changed as it went northward, and sharp gables and steep sloping lines became not only frequent, but almost universal.

The Comacine Masters, who were the great church-builders of the early days in Italy, went north in the seventh century, still pursuing their mission; to England with St. Augustine, to Germany with Boniface, and Charlemagne himself, as we know, brought them to Aix-la-Chapelle for the work at his church there.

The distinctly Rhenish variety of Romanesque ecclesiastical architecture came to its greatest development under the Suabian or Hohenstaufen line of emperors, reaching its zenith during the reign of the great Frederick Barbarossa (1152-90).

The churches at Neuss, Bonn, Sinzig, and Coblenz all underwent a necessary reconstruction in the early thirteenth century because of ravages during the terrific warfare of the rival claimants to the throne of Barbarossa.

Frederick, one claimant, was under the guardianship of Pope Innocent III., and Philip, his brother, was as devotedly cared for by the rival Pope, Gregory VIII. Finally Innocent compromised the matter by securing the election of Otho IV., of Brunswick.

With that "hotbed of heresies," Holland, this book has little to do, dealing only with three centres of religious movement there.

Holland was the storm-centre for a great struggle for religious and political freedom, and for this very reason there grew up here no great Gothic fabrics of a rank to rival those of France, England, and Germany. Still, there was a distinct and most picturesque element which entered into the church-building of Holland in the middle ages, as one notes in the remarkable church of Deventer. In the main, however, if we except the Groote Kerk at Rotterdam, St. Janskerk at Gouda, the archbishop's church at Utrecht, and the splendid edifice at Dordrecht, there is nothing in Holland architecturally great.

IV

SOME CHARACTERISTICS OF RHENISH

ARCHITECTURE

It cannot be claimed that the church-building of one nation was any more thorough or any more devoted than that of any other. All the great church-building powers of the middle ages were, it is to be presumed, possessed of the single idea of glorifying God by the building of houses in his name.

"To the rising generation," said the editor of the Architectural Magazine in 1838, "and to it alone do we look forward for the real improvement in architecture as an art of design and taste."

"The poetry of architecture" was an early and famous theme of Ruskin's, and doubtless he was sincere when he wrote the papers that are included under that general title; but the time was not then ripe for an architectural revolution, and the people could not, or would not, revert to the Gothic or even the pure Renaissance – if there ever was such a thing. We had, as a result, what is sometimes known as early Victorian, and the plush and horsehair effects of contemporary times.

In general, the churches of Germany, or at least of the Rhine provinces, are of a species as distinct from the pure Gothic, Romanesque, or Renaissance as they well can be. Except for the fact that of recent years the art nouveau has invaded Germany, there is little mediocrity of plan or execution in the ecclesiastical architecture of that country, although of late years all classes of architectural forms have taken on, in most lands, the most uncouth shapes, – church edifices in particular, – they becoming, indeed, anything but churchly.

The Renaissance, which spread from Italy just after the period when the Gothic had flowered its last, came to the north through Germany rather than through France, and so it was but natural that the Romanesque manner of building, which had come long before, had a much firmer footing, and for a much longer period, in Germany, than it had in France. Gothic came, in rudimentary forms at any rate, as early here as it did to France or England; but, with true German tenacity of purpose, her builders clung to the round-arched style of openings long after the employment of it had ceased to be the fashion elsewhere.

This, then, is the first distinctive feature of the ecclesiastical edifices erected in Germany in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries when the new Gothic forms were elsewhere budding into their utmost beauty.

One strong constructive note ever rings out, and that is that, while the Gothic was ringing its purest sound in France and even in England, at least three forces were playing their gamut in Germany, producing a species quite by itself which was certainly not Gothic any more than it was Moorish, and not Romanesque any more than was the Angevin variety of round-arched forms, which is so much admired in France.

One notably pure Gothic example, although of the earliest Gothic, is found in Notre Dame at Trèves, with perhaps another in the abbey of Altenburg near Cologne; but these are the chief ones that in any way resemble the consistent French pointed architecture which we best know as Gothic.

The Rhenish variety of Romanesque lived here on the Rhine to a far later period, notably at Bonn and Coblenz, than it did in either France or England.

German church architecture, in general, is full of local mannerisms, but the one most consistently marked is the tacit avoidance of the true ogival style, until we come to the great cathedral at Cologne, which, in truth, so far as its finished form goes, is quite a modern affair.

In journeying through Northeastern France, or through Holland or Belgium, one comes gradually upon this distinct feature of the Rhenish type of church in a manner which shows a spread of its influence.

All the Low Country churches are more or less German in their motive; so, too, are many of those of Belgium, particularly the cathedral at Tournai and the two fine churches at Liège (Ste. Croix and the cathedral), which are frankly Teutonic; while at Maastricht in Holland is almost a replica of a Rhenish-Romanesque basilica.

At Aix-la-Chapelle is the famous "Round Church" of Charlemagne, which is something neither French nor German. It has received some later century additions, but the "octagon" is still there, and it stands almost alone north of Italy, where its predecessor is found at Ravenna, the Templars' Church in London being of quite a different order.

Long years ago this Ravenna prototype, or perhaps it was this eighth-century church of Charlemagne's, gave rise to numerous circular and octagonal edifices erected throughout Germany; but all have now disappeared with the exception, it is claimed, of one at Ottmarsheim, a fragment at Essen, and the rebuilt St. Gérêon's at Cologne.

These round churches – St. Gérêon's at Cologne, the Mathias Kapelle at Kobern, and, above all, Charlemagne's Münster at Aix-la-Chapelle, and others elsewhere, notably in Italy – are doubtless a survival of a pagan influence; certainly the style of building was a favourite with the Romans, and was common even among the Greeks, where the little circular pagan temples were always a most fascinating part of the general ensemble.