полная версия

полная версияThe King's Threshold; and On Baile's Strand

William Butler Yeats

The King's Threshold; and On Baile's Strand

NOTE

Both these plays have been written for Mr. Fay’s “Irish National Theatre.” “The King’s Threshold” was played in October, 1903, and “On Baile’s Strand” will be played in February or March, 1904. Both are founded on Old Irish Prose Romances, but I have borrowed some ideas for the arrangement of my subject in “The King’s Threshold” from “Sancan the Bard,” a play published by Mr. Edwin Ellis some ten years ago.

W. B. Y.THE KING’S THRESHOLD

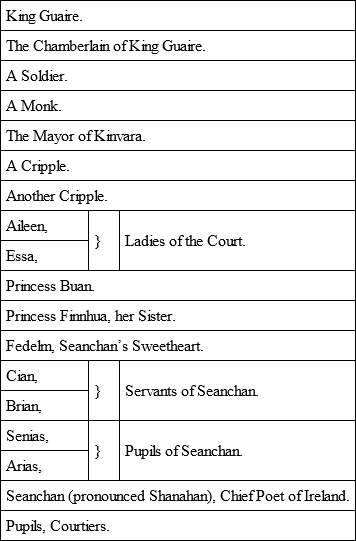

LIST OF CHARACTERS

A PROLOGUE.1

An Old Man with a red dressing-gown, red slippers and red nightcap, holding a brass candlestick with a guttering candle in it, comes on from side of stage and goes in front of the dull green curtain.

Old Man.

I’ve got to speak the prologue. [He shuffles on a few steps.] My nephew, who is one of the play actors, came to me, and I in my bed, and my prayers said, and the candle put out, and he told me there were so many characters in this new play, that all the company were in it, whether they had been long or short at the business, and that there wasn’t one left to speak the prologue. Wait a bit, there’s a draught here. [He pulls the curtain closer together.] That’s better. And that’s why I’m here, and maybe I’m a fool for my pains.

And my nephew said, there are a good many plays to be played for you, some to-night and some on other nights through the winter, and the most of them are simple enough, and tell out their story to the end. But as to the big play you are to see to-night, my nephew taught me to say what the poet had taught him to say about it. [Puts down candlestick and puts right finger on left thumb.] First, he who told the story of Seanchan on King Guaire’s threshold long ago in the old books told it wrongly, for he was a friend of the king, or maybe afraid of the king, and so he put the king in the right. But he that tells the story now, being a poet, has put the poet in the right.

And then [touches other finger] I am to say: Some think it would be a finer tale if Seanchan had died at the end of it, and the king had the guilt at his door, for that might have served the poet’s cause better in the end. But that is not true, for if he that is in the story but a shadow and an image of poetry had not risen up from the death that threatened him, the ending would not have been true and joyful enough to be put into the voices of players and proclaimed in the mouths of trumpets, and poetry would have been badly served.

[He takes up the candlestick again.

And as to what happened Seanchan after, my nephew told me he didn’t know, and the poet didn’t know, and it’s likely there’s nobody that knows. But my nephew thinks he never sat down at the king’s table again, after the way he had been treated, but that he went to some quiet green place in the hills with Fedelm, his sweetheart, where the poor people made much of him because he was wise, and where he made songs and poems, and it’s likely enough he made some of the old songs and the old poems the poor people on the hillsides are saying and singing to-day.

[A trumpet-blast.

Well, it’s time for me to be going. That trumpet means that the curtain is going to rise, and after a while the stage there will be filled up with great ladies and great gentlemen, and poets, and a king with a crown on him, and all of them as high up in themselves with the pride of their youth and their strength and their fine clothes as if there was no such thing in the world as cold in the shoulders, and speckled shins, and the pains in the bones and the stiffness in the joints that make an old man that has the whole load of the world on him ready for his bed.

[He begins to shuffle away, and then stops.

And it would be better for me, that nephew of mine to be thinking less of his play-acting, and to have remembered to boil down the knap-weed with a bit of three-penny sugar, for me to be wetting my throat with now and again through the night, and drinking a sup to ease the pains in my bones.

[He goes out at side of stage.

THE KING’S THRESHOLD

Scene: Steps before the Palace of King Guaire at Gort. A table in front of steps to right with food on it. Seanchan lying on steps to left. Pupils before steps. King on top of steps at centre.

King.I welcome you that have the masteryOf the two kinds of music; the one kindBeing like a woman, the other like a man;Both you that understand stringed instruments,And how to mingle words and notes togetherSo artfully, that all the art is but speechDelighted with its own music; and you that carryThe long twisted horn and understandThe heady notes that being without wordsCan hurry beyond time and fate and change;For the high angels that drive the horse of time,The golden one by day, by night the silver,Are not more welcome to one that loves the worldFor some fair woman’s sake.I have called you hitherTo save the life of your great master, Seanchan,For all day long it has flamed up or flickeredTo the fast-cooling hearth.Senias.When did he sicken?Is it a fever that is wasting him?King.He did not sicken, but three days agoHe said he would not eat, and lay down thereAnd has not eaten since. Till yesterdayI thought that hunger and weakness had been enough,But finding them too trifling and too lightTo hold his mouth from biting at the graveI called you hither, and have called others yet.The girl he is to wed at harvest-time,That should be of all living the most dear,Is coming from the South, and had I knownOf any other neighbours or good friendsThat might persuade him, I had brought them hither,Even though I’d to ransack the world for them.Senias.What was it put him to this work, High King?King.You will call it no great matter. Three days agoI yielded to the outcry of my courtiers,Bishops, soldiers, and makers of the law,Who long had thought it against their dignityFor a mere man of words to sit among themAt my own table; and when the meal was spreadI ordered Seanchan to good company,But to a lower table; and when he pleadedThe poet’s right, established when the worldWas first established, I said that I was KingAnd made and unmade rights at my own pleasure.And that it was the men who ruled the world,And not the men who sang to it, who should sitWhere there was the most honour. My courtiers,Bishops, soldiers, and makers of the lawShouted approval, and amid that noiseSeanchan went out, and from that hour to this,Although there is good food and drink beside him,Has eaten nothing. If a man is wronged,Or thinks that he is wronged, and will lie downUpon another’s threshold until he dies,The common people for all time to comeWill raise a heavy cry against that threshold,Even though it is the King’s. He lies there nowPerishing; he is calling against my majesty,That old custom that has no meaning in it,And as he perishes, my name in the worldIs perishing also. I cannot give wayBecause I am King, because if I give wayMy nobles would call me a weakling, and it may beThe very throne be shaken; but should youThat are his friends speak to him and persuade himTo turn his mouth from the ill-savouring graveAnd eat good food, he shall not lack my favour;For I will give plough-land and grazing-land,Or all but anything he has set his heart on.It is not all because of my good nameI’d have him live, for I have found him a manThat might well hit the fancy of a kingBanished out of his country, or a woman’s,Or any other’s that can judge a manFor what he is. But I that sit a throne,And take my measure from the needs of the state,Call his wild thought that over-runs the measure,Making words more than deeds, and his proud willThat would unsettle all, most mischievous,And he himself a most mischievous man.Senias.King, whether you did right or wrong in thisLet the King say, for all that I need sayIs that there’s nothing that cries out for deathIn the withholding of that ancient right,And that I will persuade him. Your own wordsHad been enough persuasion were it notThat he is lost in dreams that hunger makes,And therefore heedless, or lost in heedless sleep.King.I leave him to your love, that it may promisePlough-lands and grass-lands, jewels and silken wear,Or anything but that old right of the poets.[He goes out. The Pupils, who have been standing perfectly quiet, all turn towards Seanchan, and move a step nearer.

Senias.The King did wrong to abrogate our right,But Seanchan, who talks of dying for it,Talks foolishly. Look at us, Seanchan,Waken out of your dream and look at us,Who have ridden under the moon and all the day,Until the moon has all but come again,That we might be beside you.[Seanchan turns half round leaning on his elbow, and speaks as if in a dream.

Seanchan.I was but nowAt Almhuin, in a great high-raftered house,With Finn and Osgar. Odours of roast fleshRose round me and I saw the roasting spits,And then the dream was broken, and I sawGrania dividing salmon by a pool,And then I was awakened by your voice.Senias.It is your hunger that makes you dream of fleshRoasting, and for your hunger I could weep;And yet the hunger of the crane that starvesBecause the moonlight glittering on the poolAnd flinging a pale shadow has made it shy,Seems to me little more fantasticalThan this that’s blown into so great a trouble.Seanchan.[Who has turned away again.]There is much truth in that, for all things changeAt times, as if the moonlight altered them,And my mind alters as if it were the crane’s;For when the heavy body has grown weakThere’s nothing that can tether the wild mindThat being moonstruck and fantasticalGoes where it fancies. I had even thoughtI knew your voice and face, but now the wordsAre so unlikely that I needs must askWho is it that bids me put my hunger by?Senias.I am your oldest pupil, Seanchan;The one that has been with you many years,So many that you said at CandlemasThat I had almost done with school, and knewAll but all that poets understand.Seanchan.My oldest pupil. No, that cannot be;For it is someone of the courtly crowdsThat have been round about me from sunriseAnd I am tricked by dreams, but I’ll refute them.I asked the pupil that I loved the best,At Candlemas, why poetry is honoured,Wishing to know how he’d defend our craftIn distant lands among strange churlish Kings.And he’d an answer.Senias.I said the poets hungImages of the life that was in EdenAbout the childbed of the world, that it,Looking upon those images, might bearTriumphant children; but why must I stand hereRepeating an old lesson while you starve?Seanchan.Tell on, for I begin to know the voice;What evil thing will come upon the worldIf the arts perish?Senias.If the arts should perishThe world that lacked them would be like a womanThat looking on the cloven lips of a hareBrings forth a hare-lipped child.Seanchan.But that’s not all.For when I asked you how a man should guardThose images you had an answer also,If you’re the man that you have claimed to be,Comparing them to venerable thingsGod gave to men before he gave them wheat.Senias.I answered, and the word was half your own,That he should guard them, as the men of DeaGuard their four treasures, as the Grail King guardsHis holy cup, or the pale righteous horseThe jewel that is underneath his horn,Pouring out life for it, as one pours outSweet heady wine – but now I understandYou would refute me out of my own mouth;And yet a place at table near the KingIs nothing of great moment, Seanchan.How does so light a thing touch poetry?[Seanchan is now sitting up. He still looks dreamily in front of him.

Seanchan.At Candlemas you called this poetryOne of the fragile mighty things of GodThat die at an insult.Senias.[To other Pupils.] Give me some true answer.For on that day we spoke about the courtAnd said that all that was insulted thereThe world insulted, for the courtly life,Being the first comely child of the world,Is the world’s model. How shall I answer him?Can you not give me some true argument?I will not tempt him with a lying one.Arias.[Throwing himself at Seanchan’s feet.]Why did you take me from my father’s fields?If you would leave me now, what shall I love?Where shall I go, what shall I set my hand to?And why have you put music in my earsIf you would send me to the clattering houses?I will throw down the trumpet and the harp,For how could I sing verses or make musicWith none to praise me and a broken heart?Seanchan.What was it that the poets promised youIf it was not their sorrow? Do not speak.Have I not opened school on these bare steps,And are not you the youngest of my scholars?And I would have all know that when all fallsIn ruin, poetry calls out in joy,Being the scattering hand, the bursting pod,The victim’s joy among the holy flame,God’s laughter at the shattering of the world,And now that joy laughs out and weeps and burnsOn these bare steps.Arias.O Master, do not die.[Three men come in. Cian and Brian, old men carrying basket with food, and Mayor of Kinvara. They stand at the side listening.

Senias.Trouble him with no useless argument.Be silent; there is nothing we can doExcept find out the King and kneel to himAnd beg our ancient right. These three have comeTo say whatever we could say and more,And fare as badly. Come, boy, that’s no use;[He lifts the Boy up.

If it seem well that we beseech the King,Lay down your harps and trumpets on the stonesIn silence and come with me silently.Come with slow footfalls and bow all your heads,For a bowed head becomes a mourner best.[They lay the harps and trumpets down one by one and then go out very solemnly and slowly, following one another.

Cian.Let’s show the food that’s in the basket.Mayor.[Who carries an Ogham stick.] No,I must get through my speech or I’ll forget it;Besides, there is no reason why he’d eatTill he has heard my reasons.Cian.It were betterTo show what we have brought him in the basket,For we have nothing that he has not likedFrom boyhood.Brian.For we have not brought kings’ foodThat’s cooked for everybody and nobody.Mayor.You are not showing right respect to me,Or to the people of Kinvara, when you wishThat something else should come before my message.Seanchan.What brings you here? I never sent for you.Cian.He must be famishing, he looks so pale.We had better get the food out first. I tell you,That we have brought the things he likes the best.Mayor.No, no; I lost a word at every cross roadAnd maybe if I do not speak it nowI’ll have forgot it.Cian.Well, out with it quickly.Seanchan.Why, what’s this foolery?Mayor.No foolery;A message from the richest, best born townsmanOf your own town, and from your aged father.Cian.Run through it while I am getting out the food.Mayor.How was I to begin? What was the wordThat was to keep it in my memory?Wait, I have notched it on this Ogham stick.“Chief poet,” “Ireland,” “Townsman”; that is it.Chief poet of Ireland, when we heard that troubleHad come between you and the King of IrelandIt plunged us in deep sorrow, part for you,Our honoured townsman, part for our good town.The King was said to be most friendly to us,And we had reasons, as you’ll recollect,For thinking that he was about to giveThose grazing lands inland we so much need,Being pinched between the water and the rocks.But now his friendliness being ill repaidWill be turned from us and our town get nothing.But there was something else – I’ll find the wordThat was to keep it in my memory.“Pride” – that’s the word, – we would not have you think,Weighty as these considerations are,That they have been as weighty in our mindsAs our desire that one we take much pride in,A man who has been an honour to our town,Should live and prosper, therefore we beseech youTo give way in a matter of no moment,A matter of mere sentiment, a trifle,That we may always keep our pride in you.Seanchan.Their pride, their pride, what do they know of pride?My pupils do not know it, for they begFrom the King’s favour what is theirs by right,And how can men, that God has made so weakThey need a rich man’s favour every day,Know anything of pride?Cian.[To Mayor.] You have spoken it wrongly.You have forgotten something out of it about the cattle dying.Mayor.Maybe you do not know, being much away,How many of our cattle died last winterFrom lacking grass, and that there was much sicknessBecause the poor had nothing but salt fishTo live upon. The people all came outAnd stood about the doors as I went by.Seanchan.What would you have of me?For there are men that shall be born at lastAnd find sweet nurture that they may have voicesEven in anger like the strings of harps.Yet how could they be born to majestyIf I had never made the golden cradle?Mayor.What is it? “Father” – “Mother”; that is it;Your father sends this message.Cian.He is listening.Mayor.He says that he is old and that he needs you,And that the people will be pointing at himAnd he not able to lift up his headIf you should turn the King’s favour away.And he adds to it, that he cared you well,And you in your young age, and that it’s rightThat you should care him now.Cian.And when he spokeHe cried because the stiffness of his bonesPrevented him from coming.Mayor.But your motherHas sent no message, for when they had told herThe way it is between you and the KingShe said, “No message can do any good,He will not send the answer that you want;We cannot change him,” and she went indoors,Lay down upon her bed and turned her faceOut of the light. And thereupon your fatherSaid, “Tell him how she is, and that she sendsNo message.” I have nothing more to say.Cian and Brian, you can set out the food.[He sits down on steps. Seanchan is silent.

Mayor.I have a horse waiting outside the townTo bring me home, and all the neighbours waitYour answer. What answer am I to bring?Seanchan.Give them my answer – no, I have no answer:My mother knew it.Mayor.Maybe you have forgottenThat all our fields are so heaped up with stonesThat the goats famish, and the mowers mowWith knives, and that the King half promised us —Seanchan.Thrust that old cloak of yours into your mouthTill it’s done gabbling.Mayor.But —Cian.You have said enough;I knew that you would never speak it right.Seanchan.Our mothers know us, they know us to the bone,They knew us before birth, and that is whyThey know us even better than the sweetheartsUpon whose breasts we have lain.Brian.We have brought your honourThe food that you have always liked the best,Young pigeons from Kinvara, and watercressOut of the stream that’s by the blessed well,And dulse from Duras. Here is the dulse, your honour,It is wholesome, and has the good taste of the sea.Seanchan.O Brian, you would spread the table for meAs you would spread it when I was in my childhood;But all that’s finished.Mayor.I knew he would not careFor country things now that he’s grown accustomedTo the King’s dishes. I told Brian tooHe’d have his pains for nothing. But he’s old.[Goes over to table at right. While he is speaking Cian and Brian are in vain offering Seanchan food.

And what dishes! Venison from Slieve EchtgeFattened with poor men’s crops; flesh of wild pig;Not fat nor lean, but streaky and right well cured;Bread that’s the whitest that I’ve ever seen.Cian.You’re in the right, you’re in the right, he will not eat.[Pouring wine into cup.

Mayor.Bring him some wine, it will give him strength to eat.[Brian brings wine over towards Seanchan.

No wonder if the King is proud and merry,And keeps all day in the saddle, when even IAm well-nigh drunken with the odour of it,And if I dared – I dare not.Cian.Drink it, sir.Brian.Drink a few drops.Seanchan.Drink it yourself, old man,For you have come a journey, and I daresayYou did not eat or drink upon the road.Cian.How can I drink it when your honour’s thirsty?[He offers cup again. The King’s Household comes in. Chamberlain with long staff, a Soldier, a Monk, two Ladies, followed by Cripples who beg from the ladies, who keep close together at right, talking to each other at intervals. Soldier goes over to Mayor, and talks to him.

Chamberlain.Well, have you it in imagination stillTo overthrow the dignity of the King,Or is the game finished?[A pause.

How many daysWill you keep up this quarrel with the King,With the King’s nobles and myself and allWho’d gladly be your friends if you would let them?Soldier.[Who has been speaking to Mayor and Servants.]Was it you that sent his servants and the MayorOf his own town to wheedle him into life?Chamberlain.It was the King himself.Soldier.Was it worth our whileTo have got rid of him from the King’s tableIf he is to be humoured and made much of?Chamberlain.It seems that he has not eaten yet, althoughHe’s had another dozen hours of hunger.Soldier.If he’s so proud and obstinate a neckI’d let him starve.Monk.Persuade him to eat, my lord.His death would make a scandal, and stir upThe common people.Chamberlain.And I have a fancyThat if it brought misfortune on the King,Or the King’s house, we’d be as little thought ofAs summer linen when the winter’s come.Aileen.[To Cian.] You’ve had no luck, old man.Cian.We have not, lady.Aileen.Maybe he’s out of humour with your ways,Having grown used to sprightlier service.Cian.Maybe.But the King’s messengers have gone for oneThat will persuade him. [To Brian.] Come, let us go;For she might lose her way in this fine place.Come, we have been too long upon the tree,[Plucking sleeve of Mayor.

And there are little golden pippins here.Soldier.Give me the dish, I’ll hand it him myself.Aileen.I wonder if she is pretty.[Mayor and Servants have gone out.

Soldier.Eat this, old hedgehog.Sniff up the savour and unroll yourself.But if I were the King I’d make you do itWith wisps of lighted straw.Seanchan.You have rightly named me,I lie rolled up under the ragged thornsThat are upon the edge of those great watersWhere all things vanish away, and I have heardMurmurs that are the ending of all sound.I am out of life, I am rolled up, and yet,Hedgehog although I am, I’ll not unrollFor you, King’s dog. Go to the King, your master,Crouch down and wag your tail, for it may beHe has nothing now against you, and I thinkThe stripes of your last beating are all healed.Chamberlain.Don’t answer, you were never to his mind.And now you have angered him to no good purpose.But put the dish down and I will speak to him.Seanchan.You must needs keep your patience yet awhile,For I have some few mouthfuls of sweet airTo swallow before I have grown to be as civilAs any other dust.Chamberlain.You wrong us, Seanchan,There is none here but holds you in respect,And if you would only eat out of this dishThe King would show how much he honours you.Aileen.[Giving Cripple money.]You are always discontented. Look at this cripple,He has had to cover up his eyes with ragsBecause they are too weak to look at the sun,And has a crooked body, and yet he is cheerful.Stand there where he can see you.[Cripple goes over and stands in front of Seanchan, bowing and smiling.

Chamberlain.We have come to youBecause we wish you a long, prosperous life;Who could imagine you’d so take to heartBeing put from the high table.Seanchan.It was not IThat you have driven away from the high table,But the images of them that weave a dance,By the four rivers in the mountain garden.Monk.He means we have driven poetry away.Chamberlain.It is the men who are learned in the laws,Or have led the King’s armies that should sitAt the King’s table. Nor has poetryBeen altogether driven away, for I,As you should know, have written poetry,And often when the table has been clearedAnd candles lighted, the King calls for meAnd I repeat it him. My poetryIs not to be compared with yours, but stillWhere I am honoured, poetry is honouredIn some measure.Seanchan.If you are a poet,Cry out that the King’s money would not buy,Nor the high circle consecrate his head,If poets had never christened gold, and evenThe moon’s poor daughter, that most whey-faced metal,Precious; and cry out that none aliveWould ride among the arrows with high heartOr scatter with an open hand, had notOur heady craft commended wasteful virtues.And when that story’s finished, shake your coatWhere the little jewels gleam on it, and sayA herdsman sitting where the pigs had trampledMade up a song about enchanted kings,Who were so finely dressed one fancied themAll fiery, and women by the churnAnd children by the hearth caught up the songAnd murmured it until the tailors heard it.Monk.How proud these poets are! It was full timeTo break their pride.Seanchan.And I would have you sayThat when we are driven out we come againLike a great wind that runs out of the wasteTo blow the tables flat.Chamberlain.If you’d eat somethingYou’d find you have these thoughts because you are hungry.Seanchan.And when you have told them all these things, lie downOn this bare threshold and starve until the KingRestore to us the ancient right of the poets.Aileen.Let’s come away. There’s no use talking to him,For he’s resolved to die, and that’s no loss:We will go watch the hurley.Monk.You should obeyThe King’s commandment and not question it,For it is God himself who has made him king.Essa.Let’s hear his answer to the monk.Seanchan.Stoop down,For there is something I would say to you.Has that wild God of yours that was so wildWhen you’d but lately taken the King’s pay,Grown any tamer? He gave you all much troubleBeing so unruly and inconsiderate.Aileen.What does he mean?Monk.Let go my habit, Seanchan.Seanchan.Or it may be you have persuaded himTo chirp between two dishes when the KingSits down to table.Monk.Let go my habit, sir.What do I care about your insolent dreams.Seanchan.And maybe he has learnt to sing quite softlyBecause loud singing would disturb the KingWho is sitting drowsily among his friendsAfter the table has been cleared —Monk.Let go.[Seanchan has been dragged some feet, clinging to the Monk’s habit.