полная версия

полная версияKatharine Frensham: A Novel

"Thou knowest we are here to enjoy ourselves. We have come a long way. And there have not been many funerals or weddings in the valley lately."

Knutty of course understood perfectly, and exerted herself heroically to amuse every one, drinking coffee with every one in a reckless fashion, and even flirting with the one man who was left behind, an aged Gaardmand (landowner) of about ninety years. So the time passed away cheerily for all; and when Bedstemor, Solli, and the Praest arrived home from the churchyard, followed in due time by the others, the feasting began. It seemed to be the etiquette that the women should eat separately from the men. They gathered together in the parlour, where rich soup was served to them sitting; and after this opening ceremony, they were expected to stroll into the great dining-room, where a huge table, beautifully decorated with leaves, was spread with every kind of food acceptable to the Norwegian palate: trout, cooked in various ways; beef, mutton, veal, sauces, gravies, potatoes, even vegetables (a great luxury in those parts), compots, and of course the usual accompaniment of smoked mysteries. The plates, knives, and forks were arranged in solid blocks, and the guests were supposed to wait on themselves and take what they wished. They walked round the table on a voyage of inspection and reflection, carrying a plate and a fork; and having into this one plate put everything that took their fancy, they retired to their seats, and ate steadily in a business-like fashion. There was scarcely any talking. When the women were served, the men came and helped themselves in the same way, retiring with their booty either into the hall or the adjoining room. All of them made many journeys to the generous table, returning each time with a heaped-up plate in their hands, and in their minds a distinct, though silent, satisfaction that the Sollis were doing the thing in a suitable style. Every one made a splendid square meal; but Bedstemor took the prize for appetite. She was very happy and excited. Hers was the only voice heard. As Knutty said, it was refreshing to know that there was at least one cheerful person amongst those solemn one hundred and twenty guests! Knutty herself rose to the occasion with characteristic readiness. She ate nobly without intermission, as though she had been attending Norwegian peasant-funerals all her life; and she gave a mischievous wink to Gerda and Katharine every time Bedstemor rose from her seat and strode masterfully to the table in search of further fodder. No one offered any courtesy to any one else. It seemed to be the custom that each person should look after herself; and there was a look of puzzled amusement on some of the faces when Katharine attempted to wait on one or two of the guests. Nevertheless, the attention, once understood, was vaguely appreciated; and the pretty little old lady whom Katharine had found in her bedroom, soon allowed herself to be petted and spoiled by the visitors. Indeed she abandoned all her relatives, and always sat with Knutty.

This meal came to an end about four o'clock, when there was another relay of coffee. Some of the guests strolled about and picked red-currants off the bushes in Bedstemor's garden. Knutty found her way to the cowhouse and learnt from her favourite Mette that all the servants and cotters were having a splendid meal too.

"Ja, ja," Mette said, "I have eaten enough to last for two years. And the young ox tasted lovely! Didst thou eat of him? Ak, there is old Kari crying her heart out because the young ox had to be killed. Thou knowest she was fond of him. Ak, nobody has cried for Bedstefar as much as old Kari has cried for the young ox. And she wouldn't eat an inch of him – only think of that, Fröken, isn't it remarkable?"

"It certainly is," said Knutty, with a twinkle in her eye. "For most of us generally do eat up the people we love best – beginning with the tenderest part of them."

For one moment Mette looked aghast, and then light broke in upon her.

"Nei da," she said brightly, "but as long as we don't really eat them, it doesn't matter, does it?"

"It is supposed not to matter," answered Knutty, moving off to comfort old Kari, who was not only mourning for the young black ox, but also continuing to feel personally aggrieved over her disappointment about Clifford's ghost.

"Ak, ak, the young black ox!" cried Kari, when she saw her Danish friend. "Eat him? Not I, dear Fröken, I was fond of him. Ak, ak!"

"Be comforted, Kari," said Knutty soothingly. "You loved him and were good to him and didn't eat him up. What more do you want?"

"Will you tell me whether he tasted good?" asked Kari softly. "I should like to know that he was a success."

"He was delicious," said Knutty, "and I heard the Praest and the doctor speaking in praise of him. Of course they must know."

Kari nodded as if reassured, and disappeared into the cowhouse, Tante's concert-room, wiping her moist eyes with her horny hands. She came back again, and stood for a moment in the doorway.

"I cannot believe that it was not the Englishman's ghost," she said, shaking her head mysteriously. "I felt it was a ghost. I trembled all over, and my knees gave way."

"But you surely believe now that my Englishman is alive, don't you, Kari?" asked Tante, who was much amused.

"I cannot be sure," replied Kari, and she disappeared again; but Tante, knowing that she always carried on a conversation in this weird manner, waited for her sudden return.

"That is Ragnhild's sweetheart," she said in a whisper, pointing to a tall fair young man who had come down with another guest to take a look at the horses. "Nei, nei, don't you tell her I told you. He is a rich Gaardmand from the other side of the valley."

"But I have seen them together, and they don't speak a word to each other," Knutty said.

"Why should they?" asked old Kari. "There is nothing to say."

And she disappeared finally.

"My goodness!" thought Knutty, "if all nations only spoke when there was anything worth saying, what a gay world it would be."

Then Tante took a look at the guests' horses, some of them in the stable, and others tethered outside, and all eating steadily of the Sollis' corn. For the hospitality of the Gaard extended to the animals too; and it would have been a breach of etiquette if any of the guests had brought with them sacks of food for the horses; just as it would have been a breach of etiquette not to have contributed to the collection of funeral-cakes which were now being arranged on the table in the dining-room, together with jellies, fancy creams, and many kinds of home-made wines. Alan was sent by Mor Inga to summon Tante to a private view of this remarkable show. Some of the cakes had crape attached to them and bore Bedstefar's initials in icing. They were of all imaginable shapes, and looked rich and tempting. Tante's mouth watered.

"Ak," she cried, "if I could only eat them all at one mouthful!"

Every right-minded guest had the same desire when the room was thrown open to the public. And all set to work stolidly to fulfil a portion of their original impulse. Bedstemor again distinguished herself; but Alan ran her very close. Katharine and Gerda did not do badly. In fact, no one did badly at this most characteristic part of the day's feasting. Then every one went up and thanked Solli and Mor Inga, saying, "Tak for Kagen" (Thanks for the cakes). Indeed, one had to go up and say "Tak" for everything: after wine and coffee, dinner, dessert, and supper, which began about nine o'clock. No sooner was one meal finished than preparations were immediately made for the next, etiquette demanding that variety should be the order of the day. The supper-table was decorated with fresh leaves arranged after a fresh scheme, the centre being occupied by all the funeral gifts of butter, some of them in picturesque shapes of Saeters and Staburs.

Cold meats, dried meats of every kind, cold fish, dried fish, smoked fish, and cheeses innumerable were the menu of this evening meal. The guests did astonishing justice to it in their usual business-like fashion; perhaps here and there Knutty remarked 'an appetite that failed,' but, on the whole, there was no falling off from the excellent average. Bedstemor was tired, and was persuaded to go to bed. But she said up to the very end that she was bra', bra', and had had a happy day. Her old face looked a little sad, and Knutty thought that perhaps she was fretting for Bedstefar after all. Perhaps she was.

So the first day's feasting in honour of Bedstefar came to an end. The second day was a repetition of the first, except that the guests began to be more cheerful. Those who lived in the actual neighbourhood, had gone away over night and returned in the morning; but most of them had been quartered in the Gaard itself. Knutty talked to every one, and continued her flirtation with the ancient Gaardmand of ninety years, who, so she learnt, had been noted as an adept at the Halling dance. She had made him tell her of the good old times and ancient customs, and once she succeeded in drawing him on to speak of the Huldre. She had to use great tact in her questionings; but, as she always said to herself, she had been born with some tact, and had acquired a good deal more in dealing with two generations of icebergs. So she sat amongst these reserved Norwegians, and little by little, with wonderful patience and perseverance, dug a hole in their frozen heart-springs. They liked her. They said to Mor Inga:

"The fat old Danish lady is bra', bra'."

And Mor Inga whispered to her:

"Thou art a good one. They all like thee. There was a calf born last night. We have settled to call it after thy name – Knuttyros."

"I am sure I do not deserve such an honour," Tante said, trying to be humble.

"Yes, thou dost," Mor Inga answered with grave dignity, as she went off to her duties as hostess.

But Tante did not understand until Clifford explained to her that a great mark of Norwegian approval had been bestowed on her.

"Then I suppose it is like your new order of merit in England," she said; "'honour without insult.' Ah, Clifford, I hope some day, in the years to come, that your name will be found amongst the favoured few."

"Not very likely, Knutty," he said. "I belong only to the rank and file of patient workers and gropers, whose failures and mistakes prepare the way for the triumph of brighter spirits."

"Sniksnak!" said Knutty contemptuously. "Don't pretend to me that you are content with that. And don't talk to me about patience. I hate the word. It is almost as bad as balance and self-control. Balanced people, self-controlled people, patient people indeed! Get along with them! The only suitable place for them is in a herbarium amongst the other dried plants."

"But, Tante," said Gerda, who always took Knutty seriously, "there would and could be no science without patience."

"And a good thing too!" replied Knutty recklessly, winking at Katharine.

"Tante's head is turned by the unexpected honour of being chosen as god-mother to a Norwegian cow," Clifford said. "We must bear with her."

Knutty laughed. She was always glad when her Englishman teased her. She watched him as he went back into the hall and sat down near the doctor and clergyman.

"My Clifford begins to look younger again," she thought.

She watched him when Alan came and stood by him for a moment, and then went off with Jens.

"Yes," she thought, "it is all right with my icebergs now."

She glanced across to Katharine, who was doing her best to make friends with the women in the parlour.

"Dear one," she thought, "will you remember, I wonder, that I told you he will never be able to speak unless you help him?"

She watched her when Alan came in his shy way and sat down near her.

"Dear one," she thought, "the other iceberg is in love with you too, and I am not jealous. What a wonderful old woman I am! Or is it you who are wonderful, bringing love and happiness to us all? Ah, that's it!"

So the second day's feasting in honour of Bedstefar came to an end; and on the third day the men played quoits in the courtyard, and smoked and drank more lustily. The Sorenskriver, who had had various quiet disputes on the previous days with the doctor, the Foged, and the Storthingsmand, now broke forth into violent discussions with the same opponents, and was pronounced by Knutty to be at the zenith of happiness because he was at the zenith of disagreeableness! All the men were enjoying themselves in one way or another; but the women sat in the big parlour looking a little tired and bored. It was Katharine who suggested that Gerda should sing to them.

"Sing to them their own songs," she said. "You will make them so happy. If I could do anything to amuse them, I would. But if one does not know the language, what can one do?"

"You have your own language, kjaere," Gerda answered, "the language of kindness, and they have all understood it. If Tante was not so conceited, she would know that you have really been sharing with her the approval of the company."

"Nonsense," laughed Katharine. "Why, they think I am a barbarian woman from a country where there are no mountains and no Saeters! Come now, sing to them and to me. I love to hear your voice."

"So does my Ejnar," said Gerda. "Ak, I wish he were here! He would pretend not to care; but he would listen on the sly. Well, well, it is good to be without him. One has one's freedom."

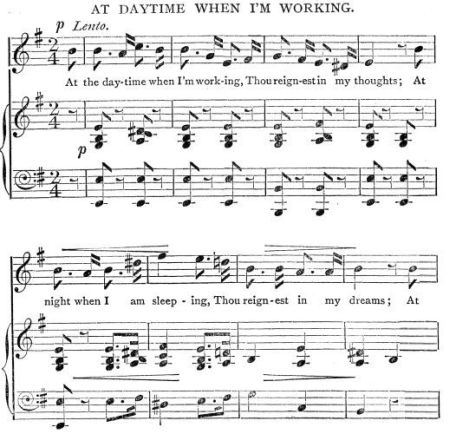

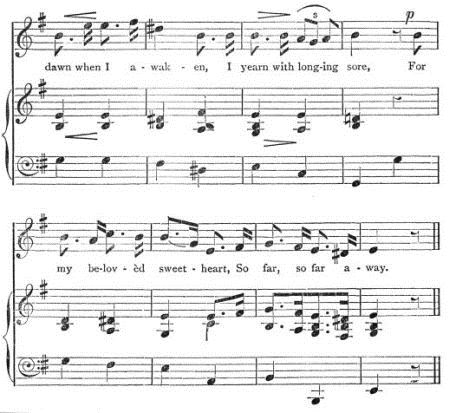

So she sat down and sang. She began with a little Swedish song:

"Om dagen vid mitt arbete" ("At daytime when I'm working").

"That is one of my Ejnar's favourites," she said, turning to Katharine.

The company began to be mildly interested. It was not the Norwegian habit of mind to be interested at once. Still, one or two faces betrayed a faint sign of pleasure; and one of the men peeped in from the hall. Then she sang another Swedish song, "Oh, hear, thou young Dora." It was so like Gerda to feel in a Swedish mood when she ought to have been feeling Norwegian.

The company seemed pleased. They nodded at each other.

Another man peeped in from the hall. Bedstemor strode masterfully into the room, and sat down near the little pocket edition of herself.

"That is another of my Ejnar's favourites," Gerda whispered, turning to Katharine again.

She paused for a moment, thinking. No one spoke.

Then she chose a Norwegian song – Aagot's mountain-song. This was it:

There was a stir of pleasure in the company. Mor Inga and Solli slipped in. Then she sang one of Kjerulf's songs, "Over de höje Fjelde."21

"Fain would I know what the world may beOver the mountains high.Mine eyes can nought but the white snow see,And up the steep sides the dark fir-tree,That climbs as if yearning to know.Ah! what if one ventured to go!""Up, heart, up! and away!Over the mountains high.For my courage is young and my soul will be gay,If no longer bound straitly and fettered I stay,But seeking yon summit to gain,No more beat my wings here in vain."The Sorenskriver came in and sat down by Katharine.

"Yes," he said, more to himself than to her, "I remember having those thoughts when I was a young boy. What should I find over the mountains? Ak, and what does one find in exchange for all one's yearning?"

Gerda had sung this beautifully. The natural melancholy of her voice suited to perfection the weird sadness of Norwegian music. The company was gratified. They knew and loved that song well, and some of them joined in timidly at the end of the last verse. The old Gaardmand crept into the room and sat near Knutty.

"I could sing as finely as I could dance the Halling," he said to Knutty, with a grim smile.

"Thou shouldst have heard me sing," said Bedstemor to Knutty. "I had a beautiful voice."

"And so had I," said the pocket edition of Bedstemor, clutching at Knutty's dress.

"Yes," answered Knutty sympathetically, "I can well believe it."

And she added to herself:

"We all had a voice, or think we had. It amounts to the same when the past is past. A most convenient thing, that past – that kind of past which only crops up when you want it!"

Then Gerda sang:

"Come haul the water, haul the wood."

This time the audience which, unbeknown to Gerda, had grown to large proportions, joined in lustily, led by Bedstemor's cracked old voice. She beat time, too, still playing the rôle of leading lady. Katharine, sitting by Gerda's side, but a little in front of the piano, saw that the hall was full of eager listeners, and that at the back of the guests were the servants of the Gaard, including Thea and the dramatic Mette, and some of the cotters, and old Kari. The music which they knew and loved had gathered them all together from courtyard, kitchen, and cowhouse. There was no listlessness on any face now: an unwilling animation, born of real pleasure, lit up the countenances of both men and women – an animation all the more interesting, so Katharine thought, because of its reluctance and shyness. It reminded her of Alan's shyness, of Clifford's too; she remembered that Clifford had said to her several times:

"I believe I am a Norwegian in spirit if not in body; I have always loved the North and yearned after it."

She glanced at him and caught him looking fixedly at her. He was thinking:

"To-morrow, when she and I go off to Peer Gynt's home together, shall I be able to speak to her as I spoke to her in my dream up at the Saeter?"

He turned away when he met her glance, and retired at once into himself.

Then Gerda sang other Norwegian songs, every one joining in with increasing enjoyment and decreasing shyness: songs about cows, pastures, Saeters, sweethearts, and Huldres, a curious mixture of quaint, even humorous words, and melancholy music.

Finally the Sorenskriver, scarcely waiting until the voices had died away, stood up, a commanding figure, a typical rugged Norwegian, and started the national song:

"Yes, we cherish this our country."

Long afterwards Katharine remembered that scene and that singing.

No voice was silent, no heart was without its thrill, no face without its sign of pride of race and country.

CHAPTER XIX

PEER GYNT'S STUE

The next morning all the guests went away. They were packed in their carioles, gigs, and carriages, and their cake-baskets were returned to them, etiquette demanding that each guest should take away a portion of another guest's funeral-cake offering. Ragnhild's sweetheart was the last to go. Knutty watched with lynx eyes to see if there was going to be any outward and visible sign of the interest which they felt in each other; but she detected none.

"Well, they must be very much in love with each other," she said to Gerda, "for there is not a single flaw in their cloak of sulkiness. Ak, ak, kjaere, I am glad the funeral is over. I have not borne up as bravely as Bedstemor; but then, of course, I have not lost a husband. That makes a difference. Now don't look shocked. I know quite well I ought not to have said that. All the same, Bedstemor's strength and spirits and appetite have been something remarkable. I believe she would like a perpetual funeral going on at the Gaard. And how lustily she sang last evening! That reminds me, you sang beautifully yesterday, and were most kind and gracious to the whole company. I think Mor Inga ought to have made you the godmother of the calf. I was proud of my Gerda. I am proud of my Gerda, although I do tease her."

"Never mind," said Gerda, "was sich liebt, sich neckt. And I am not jealous about the calf. I am a little jealous about the Englishwoman sometimes. Tante loves her."

"Yes," said Tante simply, "I love her, but quite differently from the way in which I love my botanical specimens. My botanists have their own private herbarium in my heart."

Gerda smiled.

"I like her too, Tante," she said. "You know I was not very jealous of her when my Ejnar began to pay her attentions."

"Because you knew they would not last," laughed Knutty. "You need never be anxious about him. He is not a sensible human being. He won't do anything worse than elope with a plant. Any way, he cannot elope with Miss Frensham just now, as he is safe in the Dovre mountains making love to the Ranunculus glacialis!"

"She told me she was going to Peer Gynt's stue with the Kemiker," Gerda said after a pause. "I wish I could have gone too. But my ankle is too bad."

"Ah, what a good thing!" remarked Knutty. "That gives them a chance. How I wish he would elope with her! But he won't, the silly fellow. I know him. If you see him, tell him I said he was to elope with her instantly. I am going off to the cowhouse to have a talk with my dramatic Mette and to learn the cowhouse gossip about the funeral-feast. So farewell for the present."

"I cannot think why Mette is such a favourite with you, Tante," Gerda said. "You know she isn't a respectable girl at all."

"Kjaere, don't wave the banner; for pity's sake, don't wave the banner," Tante said. "Who is respectable, I should like to know? I am sure I am not, and you are not. That is to say, we may be respectable in one direction; but that does not make up the sum-total. There, go and think that over, and be sure and keep your ankle bad; and if you see Alan, tell him to follow me to the cowhouse, for I want him to do something for me."

And so it came to pass that Clifford and Katharine were able to steal off alone to Peer Gynt's stue. They had tried several times during the funeral-feasting to escape from the company; but Mor Inga liked to have all the guests around her, and it would have seemed uncourteous if any of them had deliberately withdrawn themselves. But now they were free to go where they wished without breaking through the strict Norwegian peasant etiquette. They had long since planned this Peer Gynt expedition. It was Bedstemor who originally suggested it to Clifford. She was always saying that he must go to Peer Gynt's stue; and her persistence led him to believe that there really was some old house in the district which local tradition claimed to be Peer Gynt's childhood's home; where, as in Ibsen's wonderful poem, he, a wild, idle, selfish fellow from early years upwards, lived with his mother Ãse. Clifford had not been able to find out to his entire satisfaction whether or not this particular stue had been known as Peer Gynt's house before the publication of Ibsen's poem. Bedstemor had always known it as such, and gave most minute instructions for finding it. The old Gaardmand with whom Knutty had flirted said he had always known it as Peer Gynt's actual home; and even old Kari, when questioned, said, "Ja, Peer Gynt lived up over there." Bedstemor had a few vague stories to tell about Peer Gynt, and she ended up with, "Ja, ja, he was a wild fellow, who did wild things, and saw and heard wonderful things."

So apparently Peer Gynt was a real person who had had his home somewhere in this part of the great Gudbrandsdal; and Ibsen had probably caught up some of the stories about the real man, and woven them into the network of his hero's character. But, as Knutty said, the only thing which really mattered was the indisputable fact that Ibsen had placed the scene of three acts of his poem in the Gudbrandsdal and the mountains round about, and that they – herself, Clifford, Katharine, every one of them – were there in the very atmosphere, mental and physical, of the great poem itself.

"And the stue stands for an idea if not for a fact," she said, "like Hamlet's grave in my belovèd Elsinore. Go and enjoy; and forget, for once, to be accurate."

He thought of Knutty's words as he and Katharine left the Gaard and began to climb down the steep hillside on their way to the valley; for Peer Gynt's home was perched on another mountain-ridge, and they had first to descend from their own heights, gain the valley, walk along by the glacier-river, and pass by the old brown church before they came to the steep path which would lead them up to their goal. He said to himself: