полная версия

полная версияKatharine Frensham: A Novel

"Bedstemor is going to give trouble!" Ragnhild whispered. "Thou knowest she likes to have everything very, very grand. She wants us to do twice as much as we are doing. Ak! There she comes now. Wilt thou not keep her and talk with her? Let her tell thee again about her marriage, and how she danced her shoes through on her wedding-day."

Knutty captured Bedstemor, and the old lady sat in the porch and talked of poor Bedstefar.

"A ja," she said quaintly, "he is dead at last, poor man. He was two years dying. It seemed a long time." Then she added mysteriously:

"God has been very good to me. And I feel very happy."

"Aha, that is a good thing," said Knutty. "Nei, nei, Bedstemor, don't go and make yourself hotter in the kitchen. It is terribly hot this afternoon. Stay here with me and tell me about your wedding. Tell me the history of this old, old family. And is it true, Bedstemor, that when you were fifteen, you were carried off by the mountain-people? Tell me all about it. You can trust me. I won't breathe a word to any one."

So in this way Bedstemor was kept quiet, entertained and entertaining by speaking of herself and old days, and old ways. She told Knutty about Föderaad, the legal dues paid to the parents by the eldest son who takes over the management of the Gaard. Knutty learnt that Föderaad varied in different families; but in the Solli family it meant the possession of five cows, eight sheep, sixteen sacks of grain annually, a two-year-old calf for killing each autumn; also a pig, and a potato-field, or else the payment of 60 kroner a-year. Bedstefar's death would deprive Bedstemor of rather less than half this Föderaad; she would have three cows, five sheep, half the quantity of grain, half the value of the potato-field, and, of course, pig and calf entire; and the dower-house with all its belongings undisturbed.

But the moment arrived when Bedstemor could no longer be deterred from going into the Gaard which had once been hers, and making straight for the kitchen, in a masterful manner born of reawakened memories of ownership. Then Mor Inga came out and had a cry; but Tante patted her on the back and whispered cheering words which brought a smile to Mor Inga's tearful face.

"Ja," said Mor Inga, "thou art right, thou. One can never please one's relatives. It is stupid to expect to do so. It was a wise remark. Thou good Danish friend of mine!"

She told Tante that the old order of things was passing away, even in the more remote parts of the valley; but as Bedstefar belonged to the old order, he was to be buried according to the "gammel skik" (the old custom). But they intended to reduce the number of feast-days to the lowest number compatible with the dignity of the family and due honour to the dead – about four days; only in that case it would be necessary to show more than ordinarily lavish hospitality, so that none of the guests might feel that the family had not the means nor the desire to entertain them right royally. The kitchen had already become the scene of increased industry; and Ragnhild would soon be cooking countless jellies and innumerable fancy biscuits. No cakes were to be made; for, according to custom, the guests would bring them on the day of the funeral, or send them the day before. A sheep, an ox, and a calf were to be killed that very evening, and some one would be sent to bring back fresh Mysost from the Saeter. And two days before the burial, Jens and a fair-haired cousin Olaf would go up into the mountains to bring back a good supply of trout from the lake. Mor Inga reckoned that they would need about two hundred pounds. Then the main dwelling-house and all the brown houses would have to be thoroughly scoured and put in order.

"The guests must not see one speck of dust nor one unpolished door-handle," Mor Inga said. "For they will walk over the whole house and notice everything."

"Now remember," enjoined Knutty, as Mor Inga rose to go back to domestic difficulties, "do your best, and don't waste time trying to please any relation on earth; for it is an impossibility."

Solli passed by afterwards, and paused to say a few words to Tante. He did not often talk.

"We are in for a thunderstorm," he said. "I wish we had more water. Rain has been so scarce that we have no water with which to put the fire out, if the Gaard should be struck by lightning. There has not been such a dry season for years."

Old Kari paused a moment on her way to the house, where Bedstefar lay in sublime unconsciousness of life, the things of this world, and the bustling preparations which were being carried on for his funeral feast. He lay there decorated with scented geranium-leaves. The entrance-door of his resting-place was guarded by two young fir-trees, which Karl had cut down from the woods above. He was visited from time to time by different members of the family, and old Kari went in continually, sprinkling the ground with water, and strewing fresh sweet juniper-leaves on the floor which Bedstefar would never tread again. She held some juniper in her apron now.

"God morgen," she said, nodding to Tante. "Ak, ja! I knew Bedstefar would die yesterday. Lisaros was so restless. And there is still more trouble to come, for Fjeldros has a very sore throat!"

Then Jens and Alan came back in the gig.

"We are going to have an awful storm, Knutty," Alan said. "It is suffocating down in the valley. Where's father?"

"He went out," Knutty answered, pointing vaguely in the direction of the birch-woods.

"I'll go and meet him," Alan said.

"Don't go, Alan," Knutty said a little anxiously. "You don't know which way he will come back."

"Knutty," the boy asked shyly, "did he tell you we'd – we'd – we'd – "

"Yes," answered Knutty, with a comforting nod. "I know all about it."

"I feel quite a different fellow now," Alan said. "And father was so awfully good to me. He wasn't angry or upset or anything. And he was just splendid about mother, and – and, Knutty, I – I shall always hate myself."

"You may do that as much as you like, so long as you love him," Knutty said. "Now help me up, stakkar. I am going to take another lesson in the making of fladbröd. And Mette is beckoning to me that she is ready to begin."

As they strolled together across the courtyard to the hut where Mette was making the fladbröd, Knutty said:

"I feel ten stone lighter to-day to think that my darling icebergs have come together again. They must never drift apart any more."

"Never," said Alan eagerly; and Knutty, glancing at him out of the corner of her sharp little eyes, was satisfied that Clifford had won or was winning his son back to their old loving comradeship.

"Ah," she thought, "how unconscious the boy is of the wound he has inflicted on his father. Well, that's all right. It is only fair on the young that they should not realise the limits of their own understanding."

So they went in and watched the bright and dramatic Mette, with whom Tante had an affinity, making fladbröd for the funeral guests. She explained that she was making the best quality now: cooked potato, barley and rye, finely powdered and mixed, without water. Gaily she rolled this mystic compound until it was as thin as a sheet of paper, and she whipped it off with a flourish on to the top of the fladbröd-oven, known as a "Takke," a round, flat iron oven placed for the time being in the Peise. Then she turned it at the right moment on to its other side, and whisked it off with another flourish on to the top of a great pile of fladbröd, which looked like a ruined pillar of classic times.

"Certainly," said Tante, nodding approvingly, "thou art a true artiste, Mette."

"I do it best when I'm watched," said Mette, laughing. "Then I get excited."

"An artiste should get excited," said Knutty.

Then Knutty learnt that there were other kinds of fladbröd, the coarsest quality being made of beans, barley, and water. And she was still acquiring accurate knowledge on this important subject, and listening delightedly to Mette's animated explanations, when a clap of thunder was heard.

"Nei da!" cried Mette, "we are in for a storm. I must go and call my poor cows home. It is nearly milking-time."

Tante found Gerda, Katharine, and Alan standing together in the courtyard.

"Here comes my Ejnar," Gerda exclaimed, as a lone figure came into view on the hillside. "I am thankful he has not strayed far. Solli says we are in for an awful storm."

"And I see some one yonder," Katharine said. "I daresay that is Professor Thornton."

But it proved to be the Sorenskriver. He hastened back to the Gaard, hurrying the loitering Ejnar on with him. Every one had now returned except Clifford. The sky grew blacker and more threatening. There was no rain. Hesitating claps of thunder were heard. Knutty, Katharine, and some of the others gathered together on the verandah, which commanded the whole view of the valley, and watched the awe-inspiring exhibition of Nature's anger. The fury of the storm broke loose. The lightning was blinding, the thunder terrific. Time after time they all thought that the Gaard must have been struck. At last the rain fell heavily and more heavily. Every one was relieved to hear it; for the turf on the roofs of all the black houses and barns was as dry as matchwood. Every one in different corners of the Gaard was keeping a look-out for Clifford.

Knutty pretended to be philosophic, and said at intervals:

"He is quite safe, I am sure. He has taken shelter somewhere. Besides, he loves a thunderstorm, the silly fellow! Isn't it ridiculous? Now, I think the only pleasant place in a thunderstorm is the coal-cellar. I've found it a most consoling refuge."

And when Alan said:

"I'm getting awfully anxious about father, Knutty," she answered:

"Now, really, kjaere, don't be foolish. He can take care of himself. He was not born yesterday."

They all tried to reassure and divert the boy, all of them, including even Ejnar.

"If the Kemiker does not bring some treasure back from his long expedition," he said, "I, for one, will have nothing to say to such a contemptible wretch."

Mor Inga came to add her word of comfort.

"No doubt the Professor has taken shelter at that little lonely Saeter in the direction of F – ," she said.

"He will be comfortable there; and the old woman makes an excellent cup of coffee."

The storm died down. The early evening passed into the late evening; and still Clifford did not come. Ten o'clock struck, and still he did not come. At twelve o'clock the storm broke loose again and raged with redoubled fury. Knutty, Katharine, and Alan watched together, in Knutty's room. They could not induce the boy to go to bed. He was in great distress.

"If father would only come back," he kept on saying; "if he'd only come back. If he does not come soon, I must go and look for him."

"He will not return to-night," Katharine said. "And it would be useless to go out and look for him. As Mor Inga says, he has probably taken shelter in some Saeter, and there he will stay until the morning comes. Cheer up, Alan dear. It will be all right to-morrow."

It was she who finally persuaded the boy to go to bed; and when she looked into his room ten minutes later, he was fast asleep, worn out with the emotions and anxieties of that day. Then Knutty and she watched and waited.

"I should not be feeling so miserable about my poor iceberg," Knutty said, "if he had gone off in a happier mood. But he was quite knocked over by his interview with the boy. It was all so much worse than he had anticipated. That was what I had feared."

"But you see it is past now," Katharine said, reassuring her, – "I mean, the telling of it. He will come back, strengthened and soothed; while Alan's anxiety for his father's safety will help to put things right."

"My dear, I never thought of that," Knutty exclaimed, with a faint glimmer of cheerfulness on her old face. "You leap out to those things. You're an illuminated darling. That's what you are."

Gerda came to see them.

"Ejnar is fast asleep and dreaming of 'Salix,'" she said; "but I could not sleep, Tante. I have been thinking how dreadful it would be if the Professor had been struck by lightning."

"That is what we have all been thinking, stupid one," answered Tante gravely, "but we've had the sense not to say it. Go back to bed and dream of 'Salix' too. Much better for you."

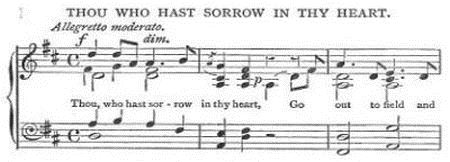

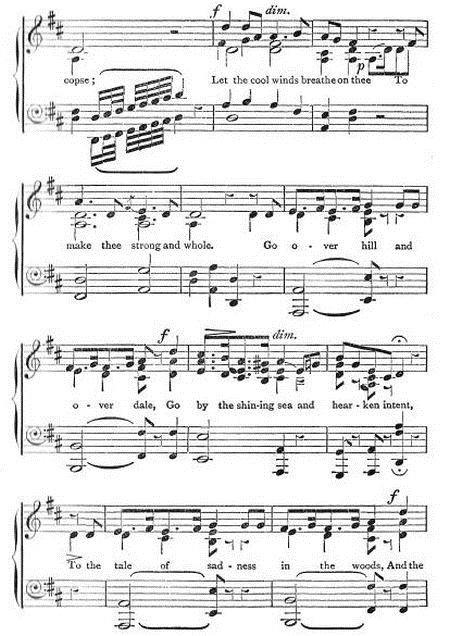

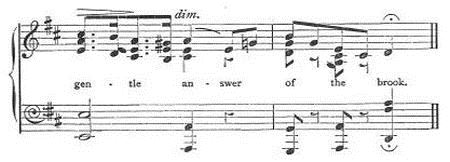

"But I came to comfort you," Gerda said "You must not send me away. Do you know, I have been thinking of that song you love so much, 'Thou who hast sorrow in thy heart.' Shall I sing to you now?"

Knutty nodded.

Gerda sang, softly, softly this Danish song: —

Knutty slept.

CHAPTER XIII

But Katharine did not sleep. Hour after hour she watched by the window, straining her eyes into the distance. And as he still did not come, and the suspense became intolerable, she went out to find him. It was five o'clock when she left the Gaard, and nearly nine when she returned.

"Has he come back?" she asked eagerly of Gerda, who was standing in the porch. Gerda shook her head.

Just then Ole Persen, the mattress-maker, arrived at the Gaard on his annual round to repair the mattresses or make up new ones from the year's accumulation of wool. Ole was the newsbringer of that part of the Gudbrandsdal, and, for a mattress-maker, was considered to be rather reliable. He would therefore have been quite useless on the staff of an Anglo-Saxon evening newspaper. He brought the news that over at Berg, about ten miles away, an Englishman had been struck dead by the lightning, and his body had been brought down from the mountains to the nearest Skyds-station (posting-station). Ole said that the people over there were sure he was an Englishman, and the doctor had said that the letters in his pocket were all from England. Ole had not seen him; but they had told him that the dead stranger was a tall thin man, with thin, clean-shaven face.

Mor Inga and Solli looked grave.

"Art thou sure he was an Englishman, Ole?" Mor Inga asked abruptly.

"I can only tell thee what they said," answered Ole. "The doctor declared only an Englishman would have so much money in his pocket."

Then Mor Inga told Knutty exactly what she had heard, neither more nor less.

"It may not be our Englishman," Mor Inga said gently, "but – "

And then Knutty told the others, first Gerda and Katharine.

"It may not be our Englishman," Knutty said, looking at them bravely, "but – "

She told Alan.

"Kjaere," she said, "it may not be your dear father, but – "

In a few minutes Knutty, Katharine, and Alan were on their way to Berg.

Solli whipped up the horses unsparingly, and admonished them with weird Norwegian words. His voice and the roar of the foss below were the only sounds heard; for at the onset no one of that anxious little company spoke a single syllable. They sat there with strained faces; they glanced at each other with silent questionings, and then as quickly turned away to look with sightless eyes at the country which was growing sterner and grimmer as the valley became narrower and shut them in from all generous share of sky and space. Suddenly there came a break in the valley, and a flood of light broke upon the travellers; they breathed a sigh of relief, and even smiled faintly, as though that unexpected blessing had, for the moment, eased the overwhelming burden of their hearts. They passed the place where the church had stood before it was swept away in the great avalanche of a hundred years ago; and on they went, skirting a fine old Gaard built near a great mound, said to be the resting-place of some renowned chieftain; on they went, in their silence and suspense. The two women glanced from time to time at the drawn face opposite, and the boy felt the silent comfort of their sympathy. When at last he spoke, the relief to them was as great as if there had been a second break in the valley. He bent forward and put his hands on their knees.

"I don't know what I should do without you both," he said simply, and he drew back again.

"Stakkar," Knutty said, "two or three miles more, and we shall know."

"Oh, Knutty," the boy cried in a sudden agony, "and I've been saying such cruel things to him, and never thinking about hurting him; and he went off all alone, and I can't bear to think that – "

Alan broke off; and once more Knutty saw before her the solitary figure of her beloved Englishman climbing up the steep hillside and disappearing into the birch-woods. She heard his words, "It will be all right for me later." Her eyes became dim; and she would have given way to her grief then and there, but for Katharine, who, notwithstanding her own great need, lent half her youthful courage, strength, and hopefulness to the old Danish woman.

"Tante," she said in her impulsive way, "for pity's sake don't forget that you are of Viking descent – a heartless, remorseless pirate, in fact."

There came a faint smile on the old Dane's face.

"Thank you for reminding me of my ancestors, kjaere," she said.

"And besides," continued Katharine, "we may yet find another break in the valley. We may find that all our fears have been only the fears of love and anxiety."

"Do you really, really think that?" the boy cried, turning to her with passionate eagerness.

"Yes, Alan," she answered, without flinching.

So she buoyed them up, and heartened herself as well, although she was saying to herself all the time:

"Oh, my love, my love, if it be indeed you lying there in the silence of death, then my womanhood lies buried with my girlhood."

At last the horses drew up at the entrance of an old Gaard which was also the Skyds-station of that district. Solli had called out immediately, and a young woman in the Gudbrandsdal dress stepped into the courtyard.

"Yes, yes, stakkar, he lies upstairs," she said, glancing sympathetically at the three travellers. "Come, I will lead the way."

They passed up the massive stairs outside the old house, and reached the covered verandah. She pointed to a door at the end of the passage.

"That is the room," she said gently; and with the fine understanding of the true Norwegian peasant, she left them.

Katharine put a detaining hand on Knutty and Alan.

"Shall I go in first and come and tell you?" she asked. "I am the stranger. It should be easier for me."

But they shook their heads, clung to her closer, and so all three passed into the room together. The room was not darkened; but sweet juniper-leaves had been spread over the floor. Katharine led them like two little stricken children to the bed of death: one of them a child indeed, and the other an old woman of seventy, childlike in her need of protecting help.

Then Katharine bent forward, and with trembling hands reverently lifted the covering from the dead man's face – and they looked.

A cry rose to their lips.

The dead man was not their beloved one.

CHAPTER XIV

Like children, too, Katharine led them from the room and took them into the old Peise-stue below. Tante had for the time being forgotten her Viking origin. Her nerve completely forsook her; and she cried abundantly, from the strain and the merciful loosening of the tension. Once she smiled through her tears as she pressed Katharine's hand and gave Alan a reassuring nod.

"Ak," she said, "this is not the correct behaviour of an abandoned sea-robber, is it?" And to Alan she added quaintly:

"Don't I make a beautiful comforter, kjaere? Ought not I to be proud of myself?"

He made no answer, but came close to her, to show that she was a comforting presence. He was painfully quiet – indeed, he seemed half-bewildered; and Katharine, glancing at his ashen face, knew that he was still under the spell of death's mysterious majesty. She wished that they had not suffered him to go into that room of death; and yet he would never have been satisfied to remain outside and take their word; it was perhaps his own father lying there, and he had to see for himself. But that part of it was over, and she felt she must break the spell for him at once. She thought of scores of things to say; but nothing seemed suitable. Suddenly, without thinking, she said:

"I know it sounds dreadfully prosaic; but I believe we should all be better for some food. I am famished. Do go and ask that nice woman if we can have breakfast, Alan."

The old Peise-stue in which they were sitting was a typical old Norwegian room, with its quaint painted furniture, its sideboard adorned with inscriptions, its Peise in the corner, fitted up in true old fashion with a shelf on the top, which was furnished with carved and painted jugs and bowls. There was, of course, a recess in the wall for the Langeleik, and a queer little cupboard for the housewife's keys. Old carved and painted mangles (manglebret), marriage gifts to several generations, hung on the walls. The Kubbe-stul,16 made from a solid block of wood, stood in the corner. At any other time Katharine and Knutty would have been deeply interested in seeing this characteristic old place. But now they scarcely noticed it. They sat together looking at nothing, and awaiting in silence the boy's return.

He came back with a different expression on his face.

"It's all right," he said. "We can have breakfast. I'm awfully hungry too."

"So am I," said Tante; and in a few minutes the servant, in her pretty costume of red bodice, white sleeves, and black skirt edged with green, served them a good meal of trout, fladbröd, and admirable flödemelk (milk with cream).

"Ripping, isn't it?" Katharine said, nodding approvingly to Alan.

"Ripping," he answered, always so glad and proud of her camaraderie.

"And now you'll go back to the Gaard," she went on, "and I believe you will find your father waiting for you there, Alan. This was a false alarm of danger, and I cannot think there is any more trouble in store."

"Do you really think that?" they both said to her.

"Yes," she answered, touched beyond words by their pathetic dependence on her. "I believe he will come down from the mountains, and that you will find him safe and sound."

"But you will be there too?" Alan said anxiously. And Knutty also said:

"But you will be there too?"

"I shall be with you in spirit," Katharine said; "but, you see, my place is here, upstairs, Knutty, with that dead Englishman, lying lonely and uncared for in a strange land. I could not go away until I, as an Englishwoman, had done something on his behalf: watched by him a little, written to his people, done something to show him that our gratitude to him for not being – ours – had passed into gentle concern for him and his."

Her voice faltered for the first time that morning when she paused at the word "ours."

"So you will go back without me," she said; "but you will tell Professor Thornton why I stayed behind. He will understand."

"Ah," said Knutty, looking at her lovingly, "you English people have the true secret of nationality."

So they left her there, sadly enough; yet knowing that for the moment her place was not with them, to whom she had already been so much, but with her dead countryman upstairs. Knutty, with many tender instructions, gave her into the charge of the people of the house. Solli's last words as he drove off were:

"Take care of the English lady. Send her safely back in your best cariole."

Katharine stood watching the carriage until it was out of sight; and then a great longing and loneliness seized her. The music and words of Gerda's Swedish song suddenly came into her remembrance:

"The lover whom thou lov'st so well,Thou shalt reach him never – ah … ah …!"And the wail of despair at the end of the verse smote as a piercing blast on her spirit.