полная версия

полная версияThe Invasion of 1910

(1) THE MILITARY JURISDICTION is hereby established. It applies to all territory of Great Britain occupied by the German Army, and to every action endangering the security of the troops by rendering assistance to the enemy. The Military Jurisdiction will be announced and placed vigorously in force in every parish by the issue of this present proclamation.

(2) ANY PERSON OR PERSONS NOT BEING BRITISH SOLDIERS, or not showing by their dress that they are soldiers:

(a) SERVING THE ENEMY as spies;

(b) MISLEADING THE GERMAN TROOPS when charged to serve as guides;

(c) SHOOTING, INJURING, OR ROBBING any person belonging to the German Army, or forming part of its personnel;

(d) DESTROYING BRIDGES OR CANALS, damaging telegraphs, telephones, electric light wires, gasometers, or railways, interfering with roads, setting fire to munitions of war, provisions, or quarters established by German troops;

(e) TAKING ARMS against the German troops,

WILL BE PUNISHED BY DEATHIN EACH CASE the officer presiding at the Council of War will be charged with the trial, and pronounce judgment. Councils of War may not pronounce ANY OTHER CONDEMNATION SAVE THAT OF DEATH.

THE JUDGMENT WILL BE IMMEDIATELY EXECUTED.

(3) TOWNS OR VILLAGES in the territory in which the contravention takes place will be compelled to pay indemnity equal to one year’s revenue.

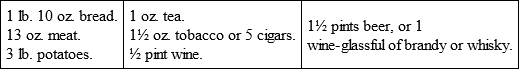

(4) THE INHABITANTS MUST FURNISH necessaries for the German troops daily as follows: —

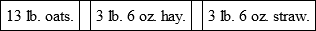

The ration for each horse: —

(ALL PERSONS WHO PREFER to pay an indemnity in money may do so at the rate of 2s. per day per man.)

(5) COMMANDERS OF DETACHED corps have the right to requisition all that they consider necessary for the well-being of their men, and will deliver to the inhabitants official receipts for goods so supplied.

WE HOPE IN CONSEQUENCE that the inhabitants of Great Britain will make no difficulty in furnishing all that may be considered necessary.

(6) AS REGARDS the individual transactions between the troops and the inhabitants, we give notice that one German mark shall be considered the equivalent to one English shilling.

The General Commanding the Ninth German Army Corps,VON KRONHELM.Beccles, September the Third, 1910.

of Westminster, couched in similar terms to that of the Lord Mayor; and a Royal Proclamation, brief but noble, urging every Briton to do his duty, to take his part in the defence of King and country, and to unfurl the banner of the British Empire that had hitherto carried peace and civilisation in every quarter of the world. Germany, whose independence had been respected, had attacked us without provocation; therefore hostilities were, alas, inevitable.

When the great poster printed in big capitals and headed by the Royal Arms made its appearance it was greeted with wild cheering.

It was a message of love from King to people – a message to the highest and to the lowest. Posted in Whitechapel at the same hour as in Whitehall, the throngs crowded eagerly about it and sang “God Save our Gracious King,” for if they had but little confidence in the War Office and Admiralty, they placed their trust in their Sovereign, the first diplomat in Europe. Therefore the loyalty was spontaneous, as it always is. They read the royal message, and cheered and cheered again.

As evening closed in yet another poster made its appearance in every city, town, and village in the country, a poster issued by military and police officers and naval officers in charge of dockyards – the order for mobilisation.

The public, however, little dreamed of the hopeless confusion in the War Office, in the various regimental dépôts throughout the country, at headquarters everywhere, and in every barracks in the kingdom. The armed forces of England were passing from a peace to a war footing; but the mobilisation of the various units – namely, its completion in men, horses, and material – was utterly impossible in the face of the extraordinary regulations which, kept a strict secret by the Council of Defence until this moment, revealed a hopeless state of things.

The disorder was frightful. Not a regiment was found fully equipped and ready to march. There was a dearth of officers, equipment, horses, provisions, of, indeed, everything. Some regiments simply existed in the pages of the Army List, but when they came to appear on parade they were mere paper phantoms. Since the Boer War the Government had, with culpable negligence, disregarded the needs of the Army, even though they had the object-lesson of the struggle between Russia and Japan before their eyes.

In many cases the well-meaning efforts on the part of volunteers proved merely a ludicrous farce. Volunteers from Glasgow found themselves due to proceed to Dorking, in Surrey; those from Aberdeen were expected at Caterham, while those from Carlisle made a start for Reading, and found themselves in the quiet old city of Durham. And in a hundred cases it was the same. Muddle, confusion, and a chain of useless regulations at Aldershot, Colchester, and York all tended to hinder the movement of troops to their points of concentration, bringing home to the authorities at last the ominous warnings of the unheeded critics of the past.

In that hour of England’s deadly peril, when not a moment should have been lost in facing the invader, nothing was ready. Men had guns without ammunition; cavalry and artillery were without horses; engineers only half-equipped; volunteers with no transport whatever; balloon sections without balloons, and searchlight units vainly trying to obtain the necessary instruments.

Horses were being requisitioned everywhere. The few horses that, in the age of motor-cars, now remained on the roads in London were quickly taken for draught, and all horses fit to ride were commandeered for the cavalry.

During the turmoil daring German spies were actively at work south of London. The Southampton line of the London and South-Western Railway was destroyed – with explosives placed by unknown hands – by the bridge over the Wey, near Weybridge, being blown up, and again that over the Mole, between Walton and Esher, while the Reading line was cut by the great bridge over the Thames at Staines being destroyed. The line, too, between Guildford and Waterloo was also rendered impassable by the wreck of the midnight train, which was blown up half-way between Wansborough and Guildford, while in several other places nearer London bridges were rendered unstable by dynamite, the favourite method apparently being to blow the crown out of an arch.

The well-laid plans of the enemy were thus quickly revealed. Among the thousands of Germans working in London, the hundred or so spies, all trusted soldiers, had passed unnoticed, but, working in unison, each little group of two or three had been allotted its task, and had previously thoroughly reconnoitred the position and studied the most rapid or effective means.

The railways to the east and north-east coasts all reported wholesale damage done on Sunday night by the advance agents of the enemy, and now this was continued on the night of Monday in the south, the objective being to hinder troops from moving north from Aldershot. This was, indeed, effectual, for only by a long détour could the troops be moved to the northern defences of London, and while many were on Tuesday entrained, others were conveyed to London by the motor-omnibuses sent down for that purpose.

Everywhere through London and its vicinity, as well as in Manchester, Birmingham, Sheffield, Coventry, Leeds, and Liverpool, motor-cars and motor-omnibuses from dealers and private owners were being requisitioned by the military authorities, for they would, it was believed, replace cavalry to a very large extent.

Wild and extraordinary reports were circulated regarding the disasters in the north. Hull, Newcastle, Gateshead, and Tynemouth had, it was believed, been bombarded and sacked. The shipping in the Tyne was burning, and the Elswick works were held by the enemy. Details were, however, very vague, as the Germans were taking every precaution to prevent information reaching London.

CHAPTER III

NEWS OF THE ENEMY

Terror and excitement reigned everywhere. The wildest rumours were hourly afloat. London was a seething stream of breathless multitudes of every class.

On Monday morning the newspapers throughout the kingdom had devoted greater part of their space to the extraordinary intelligence from Norfolk and Suffolk and Essex and other places.

That we were actually invaded was plain, but most of the newspapers happily preserved a calm, dignified tone, and made no attempt at sensationalism. The situation was far too serious.

Like the public, however, the Press had been taken entirely by surprise. The blow had been so sudden and so staggering that half the alarming reports were discredited.

In addition to the details of the enemy’s operations, as far as could as yet be ascertained, the Morning Post on Monday contained an account of a mysterious occurrence at Chatham, which read as follows: —

“Chatham, Sept. 1 (11.30 p.m.).“An extraordinary accident took place on the Medway about eight o’clock this evening. The steamer Pole Star, 1200 tons register, with a cargo of cement from Frindsbury, was leaving for Hamburg and came into collision with the Frauenlob, of Bremen, a somewhat larger boat, which was inward bound, in a narrow part of the channel about half-way between Chatham and Sheerness. Various accounts of the mishap are current, but whichever of the vessels was responsible for the bad steering or neglect of the ordinary rules of the road, it is certain that the Frauenlob was cut into by the stem of the Pole Star on her port bow, and sank almost across the channel. The Pole Star swung alongside her after the collision, and very soon afterwards sank in an almost parallel position. Tugs and steamboats carrying a number of naval officers and the port authorities are about to proceed to the scene of the accident, and if, as seems probable, there is no chance of raising the vessels, steps will be at once taken to blow them up. In the present state of our foreign relations such an obstruction directly across the entrance to one of our principal warports is a national danger, and will not be allowed to remain a moment longer than can be helped.”

“Sept. 2.“An extraordinary dénoûement has followed the collision in the Medway reported in my telegram of last night, which renders it impossible to draw any other conclusion than that the affair is anything but an accident. Everything now goes to prove that the whole business was premeditated and was the result of an organised plot with the object of ‘bottling up’ the numerous men-of-war that are now being hurriedly equipped for service in Chatham Dockyard. In the words of Scripture, ‘An enemy hath done this,’ and there can be very little doubt as to the quarter from which the outrage was engineered. It is nothing less than an outrage to perpetrate what is in reality an overt act of hostility in a time of profound peace, however much the political horizon may be darkened by lowering warclouds. We are living under a Government whose leader lost no time in announcing that no fear of being sneered at as a ‘Little Englander’ would deter him from seeking peace and ensuring it by a reduction of our naval and military armaments, even at that time known to be inadequate to the demands likely to be made upon them if our Empire is to be maintained. We trust, however, that even this parochially minded statesman will lose no time in probing the conspiracy to its depths, and in seeking instant satisfaction from those personages, however highly placed and powerful, who have committed this outrage on the laws of civilisation.

“As soon as the news of the collision reached the dockyard the senior officer at Kethole Reach was ordered by wire to take steps to prevent any vessel from going up the river, and he at once despatched several picket-boats to the entrance to warn in-coming ships of the blocking of the channel, while a couple of other boats were sent up to within a short distance of the obstruction to make assurance doubly sure. The harbour signals ordering ‘suspension of all movings,’ were also hoisted at Garrison Point.

“Among other ships which were stopped in consequence of these measures was the Van Gysen, a big steamer hailing from Rotterdam, laden, it was stated, with steel rails for the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway, which were to be landed at Port Victoria. She was accordingly allowed to proceed, and anchored, or appeared to anchor, just off the railway pier at that place. Ten minutes later the officer of the watch on board H.M.S. Medici reported that he thought she was getting under way again. It was then pretty dark. An electric searchlight being switched on, the Van Gysen was discovered steaming up the river at a considerable speed. The Medici flashed the news to the flagship, which at once fired a gun, hoisted the recall, and the Van Gysen’s number in the international code, and despatched her steam pinnace, with orders to overhaul the Dutchman and stop him at whatever cost. A number of the marines on guard were sent in her with their rifles.

“The Van Gysen seemed well acquainted with the channel, and continually increased her speed as she went up the river, so that she was within half a mile of the scene of the accident before the steamboat came up with her. The officer in charge called to the skipper through his megaphone to stop his engines and to throw him a rope, as he wanted to come on board. After pretending for some time not to understand him, the skipper slowed his engines and said, ‘Ver vel, come ‘longside gangway.’ As the pinnace hooked on at the gangway, a heavy iron cylinder cover was dropped into her from the height of the Van Gysen’s deck. It knocked the bowman overboard and crashed into the fore part of the boat, knocking a big hole in the port side forward. She swung off at an angle and stopped to pick up the man overboard. Her crew succeeded in rescuing him, but she was making water fast, and there was nothing for it but to run her into the bank. The lieutenant in charge ordered a rifle to be fired at the Van Gysen to bring her to, but she paid not the smallest attention, as might have been expected, and went on her way with gathering speed.

“The report, however, served to attract the attention of the two picket-boats which were patrolling up the river. As she turned a bend in the stream they both shot up alongside out of the darkness, and ordered her peremptorily to stop. But the only answer they received was the sudden extinction of all lights in the steamer. They kept alongside, or rather one of them did, but they were quite helpless to stay the progress of the big wall-sided steamer. The faster of the picket-boats shot ahead with the object of warning those who were busy examining the wrecks. But the Van Gysen, going all she knew, was close behind, an indistinguishable black blur in the darkness, and hardly had the officer in the picket-boat delivered his warning before she was heard close at hand. Within a couple of hundred yards of the two wrecks she slowed down, for fear of running right over them. On she came, inevitable as Fate. There was a crash as she came into collision with the central deck-houses of the Frauenlob and as her bows scraped past the funnel of the Pole Star. Then followed no fewer than half a dozen muffled reports. Her engines went astern for a moment, and down she settled athwart the other two steamers, heeling over to port as she did so. All was turmoil and confusion. None of the dockyard and naval craft present were equipped with searchlights. The harbourmaster, the captain of the yard, even the admiral superintendent, who had just come down in his steam launch, all bawled out orders.

“Lights were flashed and lanterns swung up and down in the vain endeavour to see more of what had happened. Two simultaneous shouts of ‘Man overboard!’ came from tugs and boats at opposite sides of the river. When a certain amount of order was restored it was discovered that a big dockyard tug was settling down by the head. It seems she had been grazed by the Van Gysen as she came over the obstruction, and forced against some portion of one of the foundered vessels, which had pierced a hole in her below the water-line.

“In the general excitement the damage had not been discovered, and now she was sinking fast. Hawsers were made fast to her with the utmost expedition possible in order to tow her clear of the piled-up wreckage, but it was too late. There was only just time to rescue her crew before she, too, added herself to the under-water barricade. As for the crew of the Van Gysen, it is thought that all must have gone down in her, as no trace of them has as yet been discovered, despite a most diligent search, for it was considered that, in an affair which had been so carefully planned as this certainly must have been, some provision must surely have been made for the escape of the crew. Those who have been down at the scene of the disaster report that it will be impossible to clear the channel in less than a week or ten days, using every resource of the dockyard.

“A little later I thought I would go down to the dockyard on the off-chance of picking up any further information. The Metropolitan policemen at the gate would on no account allow me to pass at that hour, and I was just turning away when by a great piece of good fortune I ran up against Commander Shelley.

“I was on board his ship as correspondent during the manœuvres of the year before last. ‘And what are you doing down here?’ was his very natural inquiry after we had shaken hands. I told him that I had been down in Chatham for a week past as special correspondent, reporting on the half-hearted preparations being made for the possible mobilisation, and took the opportunity of asking him if he could give me any further information about the collision between the three steamers in the Medway. ‘Well,’ said he, ‘the best thing you can do is to come right along with me. I have just been hawked out of bed to superintend the diving operations which will begin the moment there is a gleam of daylight.’ Needless to say, this just suited me, and I hastened to thank him and to accept his kind offer. ‘All right,’ he said, ‘but I shall have to make one small condition.’

“ ‘And that is?’ I queried.

“ ‘Merely to let me “censor” your telegrams before you send them,’ he returned. ‘You see, the Admiralty might not like to have too much said about this business, and I don’t want to find myself in the dirt-tub.’

“The stipulation was a most reasonable one, and however I disliked the notion of having probably my best paragraphs eliminated, I could not but assent to my friend’s proposition. So away we marched down the echoing spaces of the almost deserted dockyard till we arrived at the Thunderbolt pontoon. Here lay a pinnace with steam up, and, lighted down the sloping side of the old ironclad by the lantern of the policeman on duty, we stepped on board and shot out into the centre of the stream. We blew our whistles and the coxswain waved a lantern, whereupon a small tug that had a couple of dockyard lighters attached gave a hoarse ‘toot’ in response, and followed us down the river. We sped along in the darkness against a strong tide that was making up-stream, past Upnor Castle, that quaint old Tudor fortress with its long line of modern powder magazines, and along under the deeper shadows beneath Hoo Woods till we came abreast of the medley of mud flats and grass-grown islets just beyond them. Here, above the thud of the engines and the plash of the water, a thin, long-drawn-out cry wavered through the night. ‘Someone hailing the boat, sir,’ reported the lookout forward. We had all heard it. ‘Ease down,’ ordered Shelley, and hardly moving against the rushing tideway we listened for its repetition. Again the voice was raised in quavering supplication. ‘What the dickens does he say?’ queried the commander. ‘It’s German,’ I answered. ‘I know that language well. I think he’s asking for help. May I answer him?’

“ ‘By all means. Perhaps he belongs to one of those steamers.’ The same thought was in my own mind. I hailed in return, asking where he was and what he wanted. The answer came back that he was a shipwrecked seaman, who was cold, wet, and miserable, and implored to be taken off from the islet where he found himself, cut off from everywhere by water and darkness. We ran the boat’s nose into the bank, and presently succeeded in hauling on board a miserable object, wet through, and plastered from head to foot with black Medway mud. The broken remains of a cork life-belt hung from his shoulders. A dram of whisky somewhat revived him. ‘And now,’ said Shelley, ‘you’d better cross-examine him. We may get something out of the fellow.’ The foreigner, crouched down shivering in the stern-sheets half covered with a yellow oilskin that some charitable bluejacket had thrown over him, appeared to me in the light of the lantern that stood on the deck before him to be not only suffering from cold, but from terror. A few moments’ conversation with him confirmed my suspicions. I turned to Shelley and exclaimed, ‘He says he’ll tell us everything if we spare his life,’ I explained. ‘I’m sure I don’t want to shoot the chap,’ replied the commander. ‘I suppose he’s implicated in this “bottling up” affair. If he is, he jolly well deserves it, but I don’t suppose anything will be done to him. Anyway, his information may be valuable, and so you may tell him that he is all right as far as I’m concerned, and I will do my best for him with the Admiral. I daresay that will satisfy him. If not, you might threaten him a bit. Tell him anything you like if you think it will make him speak.’ To cut a long story short, I found the damp Dutchman amenable to reason, and the following is the substance of what I elicited from him.

“He had been a deck hand on board the Van Gysen. When she left Rotterdam he did not know that the trip was anything out of the way. There was a new skipper whom he had not seen before, and there were also two new mates with a new chief engineer. Another steamer followed them all the way till they arrived at the Nore. On the way over he and several other seamen were sent for by the captain and asked if they would volunteer for a dangerous job, promising them £50 a-piece if it came off all right. He and five others agreed, as did two or three stokers, and were then ordered to remain aft and not communicate with any others of the crew. Off the Nore all the remainder were transferred to the following steamer, which steamed off to the eastward. After they were gone the selected men were told that the officers all belonged to the Imperial German Navy, and by orders of the Kaiser were about to attempt to block up the Medway.

“A collision between two other ships had been arranged for, one of which was loaded with a mass of old steel rails into which liquid cement had been run, so that her hold contained a solid impenetrable block. The Van Gysen carried a similar cargo, and was provided with an arrangement for blowing holes in her bottom. The crew were provided with life-belts and the half of the money promised, and all except the captain, the engineer, and the two mates dropped overboard just before arriving at the sunken vessels. They were advised to make their way to Gravesend, and then to shift for themselves as best they could. He had found himself on a small island, and could not muster up courage to plunge into the cold water again in the darkness.

“ ‘By Jove! This means war with Germany, man! – War!’ was Shelley’s comment. At two o’clock this afternoon we knew that it did, for the news of the enemy’s landing in Norfolk was signalled down from the dockyard. We also knew from the divers that the cargo of the sunken steamers was what the rescued seaman had stated it to be. Our bottle has been fairly well corked.”

This amazing revelation showed how cleverly contrived was the German plan of hostilities. All our splendid ships at Chatham had, in that brief half-hour, been bottled up and rendered utterly useless. Yet the authorities were not blameless in the matter, for in November 1905 a foreign warship actually came up the Medway in broad daylight, and was not noticed until she began to bang away her salutes, much to the utter consternation of everyone!