полная версия

полная версияScotch Wit and Humor

Walter Henry Howe

Scotch Wit and Humor

Preface

Scotch Wit and Humor is a fairly representative collection of the type of wit and humor which is at home north of the Tweed – and almost everywhere else – for are not Scotchmen to be found everywhere? To say that wit and humor is not a native of Scotch human nature is to share the responsibility for an inaccuracy the author of which must have been as unobservant as those who repeat it. It is quite true that the humor is not always or generally on the surface – what treasure is? – and it may be true, too, that the thrifty habits of our northern friends, combined with the earnestness produced by their religious history, have brought to the surface the seriousness – amounting sometimes almost to heaviness – which is their most apparent characteristic. But under the surface will be found a rich vein of generosity, and a fund of humor, which soon cure a stranger – if he has eyes to see and is capable of appreciation – of the common error of supposing that Scotchmen are either stingy or stupid.

True, there may be the absence of the brilliancy which characterizes much of the English wit and humor, and of the inexpressible quality which is contained in Hibernian fun; but for point of neatness one may look far before discovering anything to surpass the shrewdness and playfulness to be found in the Scotch race. In fact, if Scotland had no wit and humor she would have been incapable of furnishing a man who employed such methods in construction as were introduced by the engineer of the Forth Bridge.

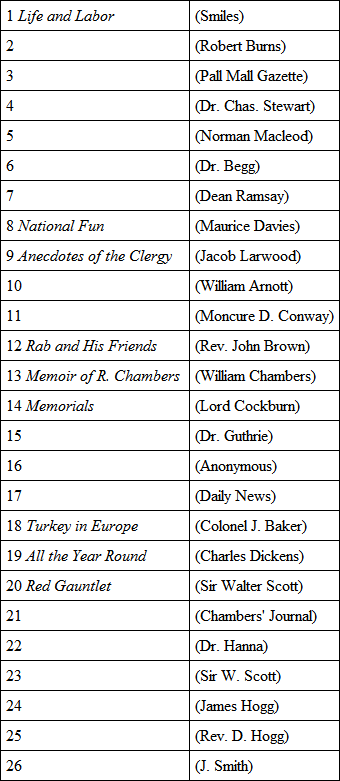

W. H. HOWE.LIST OF KNOWN WORKS AND AUTHORITIES QUOTED

(Indicated in the Text by a Corresponding Number)

Scotch Wit and Humor

Scoring a Point

A young Englishman was at a party mostly composed of Scotchmen, and though he made several attempts to crack a joke, he failed to evoke a single smile from the countenances of his companions. He became angry, and exclaimed petulantly: "Why, it would take a gimlet to put a joke into the heads of you Scotchmen."

"Ay," replied one of them; "but the gimlet wud need tae be mair pointed than thae jokes."

A Cross-Examiner Answered

Mr. A. Scott writes from Paris: More than twenty years ago the Rev. Dr. Arnott, of Glasgow, delivered a lecture to the Young Men's Christian Association, Exeter Hall, upon "The earth framed and fitted as a habitation for man." When he came to the subject of "water" he told the audience that to give himself a rest he would tell them an anecdote. Briefly, it was this: John Clerk (afterwards Lord Eldon) was being examined before a Committee of the House of Lords. In using the word water, he pronounced it in his native Doric as "watter." The noble lord, the chairman, had the rudeness to interpose with the remark, "In England, Mr. Clerk, we spell water with one 't.'" Mr. Clerk was for a moment taken aback, but his native wit reasserted itself and he rejoined, "There may na be twa 't's' in watter, my lord, but there are twa 'n's' in manners." The droll way in which the doctor told the story put the audience into fits of laughter, renewed over and over again, so that the genial old lecturer obtained the rest he desired. [3]

One "Always Right," the Other "Never Wrong"

A worthy old Ayrshire farmer had the portraits of himself and his wife painted. When that of her husband, in an elegant frame, was hung over the fireplace, the gudewife remarked in a sly manner: "I think, gudeman, noo that ye've gotten your picture hung up there, we should just put in below't, for a motto, like, 'Aye richt!'"

"Deed may ye, my woman," replied her husband in an equally pawkie tone; "and when ye got yours hung up ower the sofa there, we'll just put up anither motto on't, and say, 'Never wrang!'"

"A Nest Egg Noo!"

An old maid, who kept house in a thriving weaving village, was much pestered by the young knights of the shuttle constantly entrapping her serving-women into the willing noose of matrimony. This, for various reasons, was not to be tolerated. She accordingly hired a woman sufficiently ripe in years, and of a complexion that the weather would not spoil. On going with her, the first day after the term, to "make her markets," they were met by a group of strapping young weavers, who were anxious to get a peep at the "leddy's new lass."

One of them, looking more eagerly into the face of the favored handmaid than the rest, and then at her mistress, could not help involuntarily exclaiming, "Hech, mistress, ye've gotten a nest egg noo!"

Light Through a Crack

Some years ago the celebrated Edward Irving had been lecturing at Dumfries, and a man who passed as a wag in that locality had been to hear him.

He met Watty Dunlop the following day, who said, "Weel, Willie, man, an' what do ye think of Mr. Irving?"

"Oh," said Willie, contemptuously, "the man's crack't."

Dunlop patted him on the shoulder, with a quiet remark, "Willie, ye'Il aften see a light peeping through a crack!" [7]

A Lesson to the Marquis of Lorne

The youthful Maccallum More, who is now allied to the Royal Family of Great Britain, was some years ago driving four-in-hand in a rather narrow pass on his father's estate. He was accompanied by one or two friends – jolly young sprigs of nobility – who appeared, under the influence of a very warm day and in the prospect of a good dinner, to be wonderfully hilarious.

In this mood the party came upon a cart laden with turnips, alongside which the farmer, or his man, trudged with the most perfect self-complacency, and who, despite frequent calls, would not make the slightest effort to enable the approaching equipage to pass, which it could not possibly do until the cart had been drawn close up to the near side of the road. With a pardonable assumption of authority, the marquis interrogated the carter: "Do you know who I am, sir?" The man readily admitted his ignorance.

"Well," replied the young patrician, preparing himself for an effective dénouement, "I'm the Duke of Argyll's eldest son!"

"Deed," quoth the imperturbable man of turnips, "an' I dinna care gin ye were the deevil's son; keep ye're ain side o' the road, an' I'll keep mine."

It is creditable to the good sense of the marquis, so far from seeking to resist this impertinent rejoinder, he turned to one of his friends, and remarked that the carter was evidently "a very clever fellow."

Lessons in Theology

The answer of an old woman under examination by the minister, to the question from the Shorter Catechism, "What are the decrees of God?" could not have been surpassed by the General Assembly of the Kirk, or even the Synod of Dart, "Indeed, sir, He kens that best Himsell."

-An answer analogous to the above, though not so pungent, was given by a catechumen of the late Dr. Johnston of Leith. She answered his own question, patting him on the shoulder: "Deed, just tell it yersell, bonny doctor (he was a very handsome man); naebody can tell it better."

-A contributor (A. Halliday) to All the Year Round, in 1865, writes as follows:

When I go north of Aberdeen, I prefer to travel by third class. Your first-class Scotchman is a very solemn person, very reserved, very much occupied in maintaining his dignity, and while saying little, appearing to claim to think the more. The people whom you meet in the third-class carriages, on the other hand, are extremely free. There is no reserve about them whatever; they begin to talk the moment they enter the carriage, about the crops, the latest news, anything that may occur to them. And they are full of humor and jocularity.

My fellow-passengers on one journey were small farmers, artisans, clerks, and fishermen. They discussed everything, politics, literature, religion, agriculture, and even scientific matters in a light and airy spirit of banter and fun. An old fellow, whose hands claimed long acquaintance with the plow, gave a whimsical description of the parting of the Atlantic telegraph cable, which set the whole carriage in a roar.

"Have you ony shares in it, Sandy?" said one.

"Na, na," said Sandy. "I've left off speculation since my wife took to wearing crinolines; I canna afford it noo."

"Fat d'ye think of the rinderpest, Sandy?"

"Weel, I'm thinking that if my coo tak's it, Tibbie an' me winna ha' muckle milk to our tay."

The knotty question of predestination came up and could not be settled. When the train stopped at the next station, Sandy said: "Bide a wee, there's a doctor o' deveenity in one o' the first-class carriages. I'll gang and ask him fat he thinks aboot it." And out Sandy got to consult the doctor. We could hear him parleying with the eminent divine over the carriage door, and presently he came running back, just as the train was starting, and was bundled in, neck and crop, by the guard.

"Weel, Sandy," said his oppugner on the predestination question, "did the doctor o' deveenity gie you his opinion?"

"Ay, did he."

"An' fat did he say aboot it?"

"Weel, he just said he dinna ken an' he dinna care."

The notion of a D.D. neither kenning nor caring about the highly important doctrine of predestination, so tickled the fancy of the company that they went into fits of laughter. [38]

Double Meanings

A well-known idiot, named Jamie Frazer, belonging to the parish of Lunan, in Forfarshire, quite surprised people sometimes by his replies. The congregation of his parish had for some time distressed the minister by their habit of sleeping in church. He had often endeavored to impress them with a sense of the impropriety of such conduct, and one day when Jamie was sitting in the front gallery wide awake, when many were slumbering round him, the clergyman endeavored to awaken the attention of his hearers by stating the fact, saying: "You see even Jamie Frazer, the idiot, does not fall asleep as so many of you are doing." Jamie not liking, perhaps, to be designated, coolly replied, "An' I hadna been an idiot I wad ha' been sleepin', too." [7]

-Another imbecile of Peebles had been sitting in church for some time listening to a vigorous declamation from the pulpit against deceit and falsehood. He was observed to turn red and grow uneasy, until at last, as if wincing under the supposed attack upon himself personally, he roared out: "Indeed, meenister, there's mair leears in Peebles than me." [7]

-A minister, who had been all day visiting, called on an old dame, well known for her kindness of heart and hospitality, and begged the favor of a cup of tea. This was heartily accorded, and the old woman bustled about, getting out the best china and whatever rural delicacies were at hand to honor her unexpected guest. As the minister sat watching these preparations, his eye fell on four or five cats devouring cold porridge under the table.

"Dear me! what a number of cats," he observed. "Do they all belong to you, Mrs. Black?"

"No, sir," replied his hostess innocently; "but as I often say, a' the hungry brutes i' the country side come to me seekin' a meal o' meat."

The minister was rather at a loss for a reply.

Scotch "Fashion"

The following story, told in the "Scotch Reminiscences" of Dean Ramsay, is not without its point at the present day: "On a certain occasion a new pair of inexpressibles had been made for the laird; they were so tight that, after waxing hot and red in the attempt to try them on, he let out rather savagely at the tailor, who calmly assured him, 'It's the fashion – it's the fashion.'

"'Eh, ye haveril, is it the fashion for them no' to go on?'" [7]

Wattie Dunlop's Sympathy for Orphans

Many anecdotes of pithy and facetious replies are recorded of a minister of the South, usually distinguished as "Our Wattie Dunlop." On one occasion two irreverent young fellows determined, as they said, to "taigle" (confound) the minister. Coming up to him in the High Street of Dumfries, they accosted him with much solemnity: "Maister Dunlop, hae ye heard the news?" "What news?" "Oh, the deil's dead." "Is he?" said Mr. Dunlop, "then I maun pray for twa faitherless bairns." [7]

Highland Happiness

Sir Walter Scott, in one of his novels, gives expression to the height of a Highlander's happiness: Twenty-four bagpipes assembled together in a small room, all playing at the same time different tunes. [23]

Plain Scotch

Mr. John Clerk (afterwards Lord Eldon), in pleading before the House of Lords one day, happened to say in his broadest Scotch accent: "In plain English, ma lords."

Upon which a noble lord jocosely remarked: "In plain Scotch, you mean, Mr. Clerk."

The prompt advocate instantly rejoined: "Nae matter! in plain common sense, ma lords, and that's the same in a' languages, ye'll ken."

Caring for Their Minister

A minister was called in to see a man who was very ill. After finishing his visit, as he was leaving the house, he said to the man's wife: "My good woman, do you not go to any church at all?"

"Oh yes, sir; we gang to the Barony Kirk."

"Then why in the world did you send for me? Why didn't you send for Dr. Macleod?"

"Na, na, sir, 'deed no; we wadna risk him. Do ye no ken it's a dangerous case of typhus?"

Three Sisters All One Age

A Highland census taker contributed the following story to Chambers': I had a bad job with the Miss M'Farlanes. They are three maiden ladies – sisters. It seems the one would not trust the other to see the census paper filled up; so they agreed to bring it to me to fill in.

"Would you kindly fill in this census paper for us?" said Miss M'Farlane. "My sisters will look over and give you their particulars by and by."

Now, Miss M'Farlane is a very nice lady; though Mrs. Cameron tells me she has been calling very often at the manse since the minister lost his wife. Be that as it may, I said to her that I would be happy to fill up the paper; and asked her in the meantime to give me her own particulars. When it came to the age column, she played with her boot on the carpet, and drew the black ribbons of her silk bag through her fingers, and whispered: "You can say four-and-thirty, Mr. M'Lauchlin." "All right, ma'am," says I; for I knew she was four-and-thirty at any rate. Then Miss Susan came over – that's the second sister – really a handsome young creature, with fine ringlets and curls, though she is a little tender-eyed, and wears spectacles.

Well, when we came to the age column, Miss Susan played with one of her ringlets, and looked in my face sweetly, and said: "Mr. M'Lauchlin, what did Miss M'Farlane say? My sister, you know, is considerably older than I am – there was a brother between us."

"Quite so, my dear Miss Susan," said I; "but you see the bargain was that each was to state her own age."

"Well," said Miss Susan, still playing with her ringlets, "you can say – age, thirty-four years, Mr. M'Lauchlin."

In a little while the youngest sister came in.

"Miss M'Farlane," said she, "sent me over for the census paper."

"O, no, my dear," says I; "I cannot part with the paper."

"Well, then," said she, "just enter my name, too, Mr. M'Lauchlin."

"Quite so. But tell me, Miss Robina, why did Miss M'Farlane not fill up the paper herself?" – for Miss Robina and I were always on very confidential terms.

"Oh," she replied, "there was a dispute over particulars; and Miss M'Farlane would not let my other sister see how old she had said she was; and Miss Susan refused to state her age to Miss M'Farlane; and so, to end the quarrel, we agreed to ask you to be so kind as to fill in the paper."

"Yes, yes, Miss Robina," said I; "that's quite satisfactory; and so, I'll fill in your name now, if you please."

"Yes," she uttered, with a sigh. When we came to the age column – "Is it absolutely necessary," said she, "to fill in the age? Don't you think it is a most impertinent question to ask, Mr. M'Lauchlin?"

"Tuts, it may be so to some folk; but to a sweet young creature like you, it cannot matter a button." "Well," said Miss Robina – "but now, Mr. M'Lauchlin, I'm to tell you a great secret"; and she blushed as she slowly continued: "The minister comes sometimes to see us."

"I have noticed him rather more attentive in his visitations in your quarter of late, than usual, Miss Robina."

"Very well, Mr. M'Lauchlin; but you must not tease me just now. You know Miss M'Farlane is of opinion that he is in love with her; while Miss Susan thinks her taste for literature and her knowledge of geology, especially her pamphlet on the Old Red Sandstone and its fossils as confirming the old Mosaic record, are all matters of great interest to Mr. Frazer, and she fancies that he comes so frequently for the privilege of conversing with her. But," exclaimed Miss Robina, with a look of triumph, "look at that!" and she held in her hand a beautiful gold ring. "I have got that from the minister this very day!"

I congratulated her. She had been a favorite pupil of mine, and I was rather pleased with what happened. "But what," I asked her, "has all this to do with the census?"

"Oh, just this," continued Miss Robina, "I had no reason to conceal my age, as Mr. Frazer knows it exactly, since he baptized me. He was a young creature then, only three-and-twenty; so that's just the difference between us."

"Nothing at all, Miss Robina," said I; "nothing at all; not worth mentioning."

"In this changeful and passing world," said Miss Robina, "three-and-twenty years are not much after all, Mr. M'Lauchlin!"

"Much!" said I. "Tuts, my dear, it's nothing – just, indeed, what should be."

"I was just thirty-four last birthday, Mr. M'Lauchlin," said Miss Robina; "and the minister said the last time he called that no young lady should take the cares and responsibilities of a household upon herself till she was – well, eight-and-twenty; and he added that thirty-four was late enough."

"The minister, my dear, is a man of sense."

So thus were the Miss M'Farlanes' census schedules filled up; and if ever some one in search of the curiosities of the census should come across it, he may think it strange enough, for he will find that the three sisters M'Farlane are all ae year's bairns!

Distributing His Praises with Discernment

Will Stout was a bachelor and parish beadle, residing with his old mother who lived to the age of nearly a hundred years. In mature life he was urged by some friends to take a wife. He was very cautious, however, in regard to matrimony, and declined the advice, excusing himself on the ground "that there are many things you can say to your mither you couldna say to a fremit (strange) woman."

While beadle, he had seen four or five different ministers in the parish, and had buried two or three of them. And although his feelings became somewhat blunted regarding the sacredness of graves in general, yet he took a somewhat tender care of the spot where the ministers lay. After his extended experience, he was asked to give his deliberate judgment as to which of them he had liked best. His answer was guarded; he said he did not know, as they were all good men. But being further pressed and asked if he had no preference, after a little thought he again admitted that they were all "guid men, guid men; but Mr. Mathieson's claes fitted me best."

One of the new incumbents, knowing Will's interest in the clothes, thought that at an early stage he would gain his favor by presenting him with a coat. To make him conscious of the kindly service he was doing, the minister informed him that it was almost new. Will took the garment, examined it with a critical eye, and having thoroughly satisfied himself, pronounced it "a guid coat," but pawkily added: "When Mr. Watt, the old minister, gied me a coat, he gied me breeks as weel."

The new minister, who was fortunately gifted with a sense of humor, could not do less than complete Will's rig-out from top to toe, and so established himself as a permanent favorite with the beadle.

Mallet, Plane and Sermon – All Wooden

In olden times, the serviceable beadle was armed with a small wooden "nob" or mallet, with which he was quietly commissioned to "tap" gently but firmly the heads of careless sleepers in church during the sermon. An instance to hand is very amusing.

In the old town of Kilbarchan, which is celebrated in Scottish poetry as the birthplace of Habbie Simpson, the piper and verse maker of the clachan, once lived and preached a reverend original, whose pulpit ministrations were of the old-fashioned, hodden-gray type, being humdrum and innocent of all spirit-rousing eloquence and force. Like many of his clerical brethren, he was greatly annoyed every Sunday at the sight of several of his parishioners sleeping throughout the sermon. He was especially angry with Johnny Plane, the village joiner, who dropped off to sleep every Sunday afternoon simultaneously with the formal delivery of the text. Johnny had been "touched" by the old beadle's mallet on several occasions, but only in a gentle though persuasive manner. At last, one day the minister, provoked beyond endurance at the sight of the joiner soundly sleeping, lost his temper.

"Johnny Plane!" cried the reverend gentleman, stopping his discourse and eyeing the culprit severely, "are ye really sleeping already, and me no' half through the first head?"

The joiner, easy man, was quite oblivious to things celestial and mundane, and noticed not the rebuke.

"Andra," resumed the minister, addressing the beadle, and relapsing into informal Doric, "gang round to the wast loft (west gallery) and rap up Johnny Plane. Gie the lazy loon a guid stiff rap on the heid – he deserves 't."

Round and up to the "wast loft" the old-fashioned beadle goes, and reaching the somnolent parishioner, he rather smartly "raps" him on his bald head. Instantly, there was on the part of Johnny a sudden start-up, and between him and the worthy beadle a hot, underbreath bandying of words.

Silence restored, the reverend gentleman proceeded with his sermon as if nothing unusual had occurred. After sermon, Andra met the minister in the vestry, who at once made inquiry as to the "words" he had had with Johnny in the gallery. But the beadle was reticent and uncommunicative on the matter, and would not be questioned at the reception the joiner had given his salutary summons.

"Well, Andra," at length said the reverend gentleman, "I'll tell ye what, we must not be beaten in this matter; if the loon sleeps next Sunday during sermon, just you gang up and rap him back to reason. It's a knock wi' some force in't the chiel wants, mind that, and spare not."

"Deed no, sir" was the beadle's canny reply. "I'll no' disturb him, sleepin' or waukin', for some time to come. He threatens to knock pew-Bibles and hymn-books oot o' me, if I again daur to 'rap' him atween this and Martinmas. If Johnny's to be kept frae sleepin', minister, ye maun just pit the force into yer sermon."

Using Their Senses

The following story is told by one of the officers engaged in taking a census: One afternoon, I called up at Whinny Knowes, to get their schedule; and Mrs. Cameron invited me to stay to tea, telling me what a day they had had at "Whins" with the census paper.

"'First of all,' said she, 'the master there' – pointing to her husband – 'said seriously that every one must tell their ages, whether they were married or not, and whether they intended to be married, and the age and occupation of their sweethearts – in fact, that every particular was to be mentioned. Now, Mr. M'Lauchlin, our two servant lasses are real nice girls; but save me! what a fluster this census paper has put them in. Janet has been ten years with us, and is a most superior woman, with good sense; but at this time she is the most distressed of the two. After family worship last night, she said she would like a word o' the master himsel'.'