полная версия

полная версияThe Works of Robert Louis Stevenson – Swanston Edition. Volume 14

XXXI

Sing clearlier, Muse, or evermore be still,Sing truer or no longer sing!No more the voice of melancholy JaquesTo wake a weeping echo in the hill;But as the boy, the pirate of the spring,From the green elm a living linnet takes,One natural verse recapture – then be still.XXXII

A CAMP 2

The bed was made, the room was fit,By punctual eve the stars were lit;The air was still, the water ran,No need was there for maid or man,When we put up, my ass and I,At God’s green caravanserai.XXXIII

THE COUNTRY OF THE CAMISARDS1

We travelled in the print of olden wars;Yet all the land was green;And love we found, and peace,Where fire and war had been.They pass and smile, the children of the sword —No more the sword they wield;And O, how deep the cornAlong the battlefield!XXXIV

SKERRYVORE

For love of lovely words, and for the sakeOf those, my kinsmen and my countrymen,Who early and late in the windy ocean toiledTo plant a star for seamen, where was thenThe surfy haunt of seals and cormorants:I, on the lintel of this cot, inscribeThe name of a strong tower.XXXV

SKERRYVORE

THE PARALLEL

Here all is sunny, and when the truant gullSkims the green level of the lawn, his wingDispetals roses; here the house is framedOf kneaded brick and the plumed mountain pine,Such clay as artists fashion and such woodAs the tree-climbing urchin breaks. But thereEternal granite hewn from the living isleAnd dowelled with brute iron, rears a towerThat from its wet foundation to its crownOf glittering glass, stands, in the sweep of winds,Immovable, immortal, eminent.XXXVI

My house, I say. But hark to the sunny dovesThat make my roof the arena of their loves,That gyre about the gable all day longAnd fill the chimneys with their murmurous song:Our house, they say; and mine, the cat declaresAnd spreads his golden fleece upon the chairs;And mine the dog, and rises stiff with wrathIf any alien foot profane the path.So too the buck that trimmed my terraces,Our whilome gardener, called the garden his;Who now, deposed, surveys my plain abodeAnd his late kingdom, only from the road.XXXVII

My body which my dungeon is,And yet my parks and palaces: —Which is so great that there I goAll the day long to and fro,And when the night begins to fallThrow down my bed and sleep, while allThe building hums with wakefulness —Even as a child of savagesWhen evening takes her on her way(She having roamed a summer’s dayAlong the mountain-sides and scalp),Sleeps in an antre of that alp: —Which is so broad and high that there,As in the topless fields of air,My fancy soars like to a kiteAnd faints in the blue infinite: —Which is so strong, my strongest throesAnd the rough world’s besieging blowsNot break it, and so weak withal,Death ebbs and flows in its loose wallAs the green sea in fishers’ nets,And tops its topmost parapets: —Which is so wholly mine that ICan wield its whole artillery,And mine so little, that my soulDwells in perpetual control,And I but think and speak and doAs my dead fathers move me to: —If this born body of my bonesThe beggared soul so barely owns,What money passed from hand to hand,What creeping custom of the land,What deed of author or assign,Can make a house a thing of mine?XXXVIII

Say not of me that weakly I declinedThe labours of my sires, and fled the sea,The towers we founded and the lamps we lit,To play at home with paper like a child.But rather say: In the afternoon of timeA strenuous family dusted from its handsThe sand of granite, and beholding farAlong the sounding coast its pyramidsAnd tall memorials catch the dying sun,Smiled well content, and to this childish taskAround the fire addressed its evening hours.BOOK II

IN SCOTS

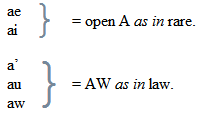

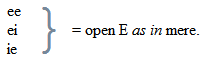

The human conscience has fled of late the troublesome domain of conduct for what I should have supposed to be the less congenial field of art: there she may now be said to rage, and with special severity in all that touches dialect: so that in every novel the letters of the alphabet are tortured, and the reader wearied, to commemorate shades of mispronunciation. Now, spelling is an art of great difficulty in my eyes, and I am inclined to lean upon the printer, even in common practice, rather than to venture abroad upon new quests. And the Scots tongue has an orthography of its own, lacking neither “authority nor author.” Yet the temptation is great to lend a little guidance to the bewildered Englishman. Some simple phonetic artifice might defend your verses from barbarous mishandling, and yet not injure any vested interest. So it seems at first; but there are rocks ahead. Thus, if I wish the diphthong ou to have its proper value, I may write oor instead of our; many have done so and lived, and the pillars of the universe remained unshaken. But if I did so, and came presently to doun, which is the classical Scots spelling of the English down, I should begin to feel uneasy; and if I went on a little further, and came to a classical Scots word, like stour or dour or clour, I should know precisely where I was – that is to say, that I was out of sight of land on those high seas of spelling reform in which so many strong swimmers have toiled vainly. To some the situation is exhilarating; as for me, I give one bubbling cry and sink. The compromise at which I have arrived is indefensible, and I have no thought of trying to defend it. As I have stuck for the most part to the proper spelling, I append a table of some common vowel sounds which no one need consult; and just to prove that I belong to my age and have in me the stuff of a reformer, I have used modification marks throughout. Thus I can tell myself, not without pride, that I have added a fresh stumbling-block for English readers, and to a page of print in my native tongue have lent a new uncouthness. Sed non nobis.

I note again, that among our new dialecticians, the local habitat of every dialect is given to the square mile. I could not emulate this nicety if I desired; for I simply wrote my Scots as well as I was able, not caring if it hailed from Lauderdale or Angus, from the Mearns or Galloway; if I had ever heard a good word, I used it without shame; and when Scots was lacking, or the rhyme jibbed, I was glad (like my betters) to fall back on English. For all that, I own to a friendly feeling for the tongue of Fergusson and of Sir Walter, both Edinburgh men; and I confess that Burns has always sounded in my ear like something partly foreign. And indeed I am from the Lothians myself; it is there I heard the language spoken about my childhood; and it is in the drawling Lothian voice that I repeat it to myself. Let the precisians call my speech that of the Lothians. And if it be not pure, alas! what matters it? The day draws near when this illustrious and malleable tongue shall be quite forgotten; and Burns’s Ayrshire, and Dr. MacDonald’s Aberdeen-awa’, and Scott’s brave, metropolitan utterance will be all equally the ghosts of speech. Till then I would love to have my hour as a native Maker, and be read by my own countryfolk in our own dying language; an ambition surely rather of the heart than of the head, so restricted as it is in prospect of endurance, so parochial in bounds of space.

TABLE OF COMMON SCOTTISH VOWEL SOUNDS

ea = open E as in mere, but this with exceptions, as heather = heather, wean = wain, lear = lair.

oa = open O as in more.

ou = doubled O as in poor.

ow = OW as in bower.

u = doubled O as in poor.

ui or ü before R = (say roughly) open A as in rare.

ui or ü before any other consonant = (say roughly) close I as in grin.

y = open I as in kite.

i = pretty nearly what you please, much as in English, Heaven guide the reader through that labyrinth! But in Scots it dodges usually from the short I, as in grin, to the open E as in mere. Find and blind, I may remark, are pronounced to rhyme with the preterite of grin.

I

THE MAKER TO POSTERITY

Far ’yont amang the years to be,When a’ we think, an’ a’ we see,An’ a’ we luve, ’s been dung ajeeBy time’s rouch shouther,An’ what was richt and wrang for meLies mangled throu’ther,It’s possible – it’s hardly mair —That some ane, ripin’ after lear —Some auld professor or young heir,If still there’s either —May find an’ read me, an’ be sairPerplexed, puir brither!“What tongue does your auld bookie speak?”He’ll speir; an’ I, his mou’ to steik:“No’ bein’ fit to write in Greek,I wrote in Lallan,Dear to my heart as the peat-reek,Auld as Tantallon.“Few spak it than, an’ noo there’s nane.My puir auld sangs lie a’ their lane,Their sense, that aince was braw an’ plain,Tint a’thegither,Like runes upon a standin’ staneAmang the heather.“But think not you the brae to speel;You, tae, maun chow the bitter peel;For a’ your lear, for a’ your skeel,Ye’re nane sae lucky;An’ things are mebbe waur than weelFor you, my buckie.“The hale concern (baith hens an’ eggs,Baith books an’ writers, stars an’ clegs)Noo stachers upon lowsent legsAn’ wears awa’;The tack o’ mankind, near the dregs,Rins unco law.“Your book, that in some braw new tongueYe wrote or prentit, preached or sung,Will still be just a bairn, an’ youngIn fame an’ years,Whan the hale planet’s guts are dungAbout your ears;“An’ you, sair gruppin’ to a sparOr whammled wi’ some bleezin’ star,Cryin’ to ken whaur deil ye are,Hame, France, or Flanders —Whang sindry like a railway carAn’ flie in danders.”II

ILLE TERRARUM

Frae nirly, nippin’, Eas’lan’ breeze,Frae Norlan’ snaw, an’ haar o’ seas,Weel happit in your gairden trees,A bonny bit,Atween the muckle Pentland’s knees,Secure ye sit.Beeches an’ aiks entwine their theek,An’ firs, a stench, auld-farrant clique.A simmer day, your chimleys reek,Couthy and bien;An’ here an’ there your windies keekAmang the green.A pickle plats an’ paths an’ posies,A wheen auld gillyflowers an’ roses:A ring o’ wa’s the hale enclosesFrae sheep or men:An’ there the auld housie beeks an’ dozes,A’ by her lane.The gairdner crooks his weary backA’ day in the pitaty-track,Or mebbe stops a while to crackWi’ Jane the cook,Or at some buss, worm-eaten-black,To gie a look.Frae the high hills the curlew ca’s;The sheep gang baaing by the wa’s;Or whiles a clan o’ roosty crawsCangle thegither;The wild bees seek the gairden raws,Weariet wi’ heather.Or in the gloamin’ douce an’ greyThe sweet-throat mavis tunes her lay;The herd comes linkin’ doun the brae;An’ by degreesThe muckle siller müne maks wayAmang the trees.Here aft hae I, wi’ sober heart,For meditation sat apairt,When orra loves or kittle artPerplexed my mind;Here socht a balm for ilka smartO’ humankind.Here aft, weel neukit by my lane,Wi’ Horace, or perhaps Montaigne,The mornin’ hours hae come an’ ganeAbüne my heid —I wadna gi’en a chucky-staneFor a’ I’d read.But noo the auld city, street by street,An’ winter fu’ o’ snaw an’ sleet,A while shut in my gangrel feetAn’ goavin’ mettle;Noo is the soopit ingle sweet,An’ liltin’ kettle.An’ noo the winter winds complain;Cauld lies the glaur in ilka lane;On draigled hizzie, tautit weanAn’ drucken lads,In the mirk nicht, the winter rainDribbles an’ blads.Whan bugles frae the Castle rock,An’ beaten drums wi’ dowie shock,Wauken, at cauld-rife sax o’clock,My chitterin’ frame,I mind me on the kintry cock,The kintry hame.I mind me on yon bonny bield;An’ Fancy traivels far afieldTo gaither a’ that gairdens yieldO’ sun an’ Simmer:To hearten up a dowie chield,Fancy’s the limmer!III

When aince Aprile has fairly come,An’ birds may bigg in winter’s lum,An’ pleesure’s spreid for a’ and someO’ whatna state,Love, wi’ her auld recruitin’ drum,Than taks the gate.The heart plays dunt wi’ main an’ micht;The lasses’ een are a’ sae bricht,Their dresses are sae braw an’ ticht,The bonny birdies! —Puir winter virtue at the sichtGangs heels ower hurdies.An’ aye as love frae land to landTirls the drum wi’ eident hand,A’ men collect at her command,Toun-bred or land’art,An’ follow in a denty bandHer gaucy standart.An’ I, wha sang o’ rain an’ snaw,An’ weary winter weel awa’,Noo busk me in a jacket braw,An’ tak my placeI’ the ram-stam, harum-scarum raw,Wi’ smilin’ face.IV

A MILE AN’ A BITTOCK

A mile an’ a bittock, a mile or twa,Abüne the burn, ayont the law,Davie an’ Donal’ an’ Cherlie an’ a’,An’ the müne was shinin’ clearly!Ane went hame wi’ the ither, an’ thenThe ither went hame wi’ the ither twa men,An’ baith wad return him the service again,An’ the müne was shinin’ clearly!The clocks were chappin’ in house an’ ha’,Eleeven, twal an’ ane an’ twa;An’ the guidman’s face was turnt to the wa’An’ the müne was shinin’ clearly!A wind got up frae affa the sea,It blew the stars as clear’s could be,It blew in the een of a’ o’ the three,An’ the müne was shinin’ clearly!Noo, Davie was first to get sleep in his head,“The best o’ frien’s maun twine,” he said;“I’m weariet, an’ here I’m awa’ to my bed.”An’ the müne was shinin’ clearly!Twa o’ them walkin’ an’ crackin’ their lane,The mornin’ licht cam grey an’ plain,An’ the birds they yammert on stick an’ stane,An’ the müne was shinin’ clearly!O years ayont, O years awa’,My lads, ye’ll mind whate’er befa’ —My lads, ye’ll mind on the bield o’ the law,When the müne was shinin’ clearly.V

A LOWDEN SABBATH MORN

The clinkum-clank o’ Sabbath bellsNoo to the hoastin’ rookery swells,Noo faintin’ laigh in shady dells,Sounds far an’ near,An’ through the simmer kintry tellsIts tale o’ cheer.An’ noo, to that melodious play,A’ deidly awn the quiet sway —A’ ken their solemn holiday,Bestial an’ human,The singin’ lintie on the brae,The restin’ plou’man.He, mair than a’ the lave o’ men,His week completit joys to ken;Half-dressed, he daunders out an’ in,Perplext wi’ leisure;An’ his raxt limbs he’ll rax againWi’ painfü’ pleesure.The steerin’ mither strang afitNoo shoos the bairnies but a bit;Noo cries them ben, their Sinday shüitTo scart upon them,Or sweeties in their pooch to pit,Wi’ blessin’s on them.The lasses, clean frae tap to taes,Are busked in crunklin’ underclaes;The gartened hose, the weel-fllled stays,The nakit shift,A’ bleached on bonny greens for days,An’ white’s the drift.An’ noo to face the kirkward mile:The guidman’s hat o’ dacent style,The blackit shoon we noo maun fyleAs white’s the miller:A waefü’ peety tae, to spileThe warth o’ siller.Our Marg’et, aye sae keen to crack,Douce-stappin’ in the stoury track,Her emeralt goun a’ kiltit backFrae snawy coats,White-ankled, leads the kirkward packWi’ Dauvit Groats.A thocht ahint, in runkled breeks,A’ spiled wi’ lyin’ by for weeks,The guidman follows closs, an’ cleiksThe sonsie missis;His sarious face at aince bespeaksThe day that this is.And aye an’ while we nearer drawTo whaur the kirkton lies alaw,Mair neebours, comin’ saft an’ slawFrae here an’ there,The thicker thrang the gate an’ cawThe stour in air.But hark! the bells frae nearer clang;To rowst the slaw their sides they bang;An’ see! black coats a’ready thrangThe green kirkyaird;And at the yett, the chestnuts spangThat brocht the laird.The solemn elders at the plateStand drinkin’ deep the pride o’ state:The practised hands as gash an’ greatAs Lords o’ Session;The later named, a wee thing blateIn their expression.The prentit stanes that mark the deid,Wi’ lengthened lip, the sarious read;Syne wag a moraleesin’ heid,An’ then an’ thereTheir hirplin’ practice an’ their creedTry hard to square.It’s here our Merren lang has lain,A wee bewast the table-stane;An’ yon’s the grave o’ Sandy Blane;An’ further ower,The mither’s brithers, dacent men!Lie a’ the fower.Here the guidman sall bide aweeTo dwall amang the deid; to seeAuld faces clear in fancy’s e’e;Belike to hearAuld voices fa’in’ saft an’ sleeOn fancy’s ear.Thus, on the day o’ solemn things,The bell that in the steeple swingsTo fauld a scaittered faim’ly ringsIts walcome screed;An’ just a wee thing nearer bringsThe quick an’ deid.But noo the bell is ringin’ in;To tak their places, folk begin;The minister himsel’ will shüneBe up the gate,Filled fu’ wi’ clavers about sinAn’ man’s estate.The tünes are up —French, to be shüre,The faithfü’ French, an’ twa-three mair;The auld prezentor, hoastin’ sair,Wales out the portions,An’ yirks the tüne into the airWi’ queer contortions.Follows the prayer, the readin’ next,An’ than the fisslin’ for the text —The twa-three last to find it, vextBut kind o’ proud;An’ than the peppermints are raxed,An’ southernwood.For noo’s the time whan pows are seenNid-noddin’ like a mandareen;When tenty mithers stap a preenIn sleepin’ weans;An’ nearly half the parochineForget their pains.There’s just a waukrif twa or three:Thrawn commentautors sweer to ’gree,Weans glowrin’ at the bumlin’ beeOn windie-glasses,Or lads that tak a keek a-gleeAt sonsie lasses.Himsel’, meanwhile, frae whaur he cocksAn’ bobs belaw the soundin’-box,The treasures of his words unlocksWi’ prodigality,An’ deals some unco dingin’ knocksTo infidality.Wi’ sappy unction, hoo he burkesThe hopes o’ men that trust in works,Expounds the fau’ts o’ ither kirks,An’ shaws the best o’ themNo’ muckle better than mere Turks,When a’s confessed o’ them.Bethankit! what a bonny creed!What mair would ony Christian need? —The braw words rummle ower his heid,Nor steer the sleeper;An’ in their restin’ graves, the deidSleep aye the deeper.Note. – It may be guessed by some that I had a certain parish in my eye, and this makes it proper I should add a word of disclamation. In my time there have been two ministers in that parish. Of the first I have a special reason to speak well, even had there been any to think ill. The second I have often met in private and long (in the due phrase) “sat under” in his church, and neither here nor there have I heard an unkind or ugly word upon his lips. The preacher of the text had thus no original in that particular parish; but when I was a boy, he might have been observed in many others; he was then (like the schoolmaster) abroad; and by recent advices, it would seem he has not yet entirely disappeared. – [R. L. S.]

VI

THE SPAEWIFE

O, I wad like to ken – to the beggar-wife says I —Why chops are guid to brander and nane sae guid to fry.An’ siller, that’s sae braw to keep, is brawer still to gi’e.– It’s gey an’ easy speirin’, says the beggar-wife to me.O, I wad like to ken – to the beggar-wife says I —Hoo a’ things come to be whaur we find them when we try.The lassies in their claes an’ the fishes in the sea.– It’s gey an’ easy speirin’, says the beggar-wife to me.O’ I wad like to ken – to the beggar-wife says I —Why lads are a’ to sell an’ lasses a’ to buy;An’ naebody for dacency but barely twa or three.– It’s gey an’ easy speirin’, says the beggar-wife to me.O, I wad like to ken – to the beggar-wife says I —Gin death’s as shüre to men as killin’ is to kye,Why God has filled the yearth sae fu’ o’ tasty things to pree.– It’s gey an’ easy speirin’, says the beggar-wife to me.O, I wad like to ken – to the beggar-wife says I —The reason o’ the cause an’ the wherefore o’ the why,Wi’ mony anither riddle brings the tear into my e’e.– It’s gey an’ easy speirin’, says the beggar-wife to me.VII

THE BLAST – 1875

It’s rainin’. Weet’s the gairden sod,Weet the lang roads whaur gangrels plod —A maist unceevil thing o’ GodIn mid July —If ye’ll just curse the sneckdraw, dod!An’ sae wull I!He’s a braw place in Heev’n, ye ken,An’ lea’s us puir, forjaskit menClamjamfried in the but and benHe ca’s the earth —A wee bit inconvenient denNo muckle worth;An’ whiles, at orra times, keeks out,Sees what puir mankind are about;An’ if He can, I’ve little doubt,Upsets their plans;He hates a’ mankind, brainch and root,An’ a’ that’s man’s.An’ whiles, whan they tak’ heart again,An’ life i’ the sun looks braw an’ plain,Doun comes a jaw o’ droukin’ rainUpon their honours —God sends a spate out ower the plain,Or mebbe thun’ers.Lord safe us, life’s an unco thing!Simmer and Winter, Yule an’ Spring,The damned, dour-heartit seasons bringA feck o’ trouble.I wadna try ’t to be a king —No, nor for double.But since we’re in it, willy-nilly,We maun be watchfü’, wise an’ skilly,An’ no’ mind ony ither billy,Lassie nor God.But drink – that’s my best counsel till ’e;Sae tak’ the nod.VIII

THE COUNTERBLAST – 1886

My bonny man, the warld, it’s true,Was made for neither me nor you;It’s just a place to warstle through,As Job confessed o’t;And aye the best that we’ll can doIs mak’ the best o’t.There’s rowth o’ wrang, I’m free to say:The simmer brunt, the winter blae,The face of earth a’ fyled wi’ clayAn’ dour wi’ chuckies,An’ life a rough an’ land’art playFor country buckies.An’ food’s anither name for clart;An’ beasts an’ brambles bite an’ scart;An’ what would WE be like, my heart!If bared o’ claethin’?– Aweel, I canna mend your cart:It’s that or naethin’.A feck o’ folk frae first to lastHave through this queer experience passed;Twa-three, I ken, just damn an’ blastThe hale transaction;But twa-three ithers, east an’ wast,Fand satisfaction.Whaur braid the briery muirs expand,A waefü’ an’ a weary land,The bumble-bees, a gowden band,Are blithely hingin’;An’ there the canty wanderer fandThe laverock singin’.Trout in the burn grow great as herr’n’;The simple sheep can find their fair’n’;The winds blaws clean about the cairnWi’ caller air;The muircock an’ the barefit bairnAre happy there.Sic-like the howes o’ life to some:Green loans whaur they ne’er fash their thumb,But mark the muckle winds that come,Soopin’ an’ cool,Or hear the powrin’ burnie drumIn the shilfa’s pool.The evil wi’ the guid they tak’;They ca’ a grey thing grey, no’ black;To a steigh brae a stubborn backAddressin’ daily;An’ up the rude, unbieldy trackO’ life, gang gaily.What you would like’s a palace ha’,Or Sinday parlour dink an’ brawWi’ a’ things ordered in a rawBy denty leddies.Weel, then, ye canna hae’t: that’s a’That to be said is.An’ since at life ye’ve ta’en the grue,An’ winna blithely hirsle through,Ye’ve fund the very thing to do —That’s to drink speerit;An’ shüne we’ll hear the last o’ you —An’ blithe to hear it!The shoon ye coft, the life ye lead,Ithers will heir when aince ye’re deid;They’ll heir your tasteless bite o’ breid,An’ find it sappy;They’ll to your dulefü’ house succeed,An’ there be happy.As whan a glum an’ fractious weanHas sat an’ sullened by his laneTill, wi’ a rowstin’ skelp, he’s ta’enAn’ shoo’d to bed —The ither bairns a’ fa’ to play’n’,As gleg’s a gled.IX

THE COUNTERBLAST IRONICAL

It’s strange that God should fash to frameThe yearth and lift sae hie,An’ clean forget to explain the sameTo a gentleman like me.Thae gusty, donnered ither folk,Their weird they weel may dree;But why present a pig in a pokeTo a gentleman like me?Thae ither folk their parritch eatAn’ sup their sugared tea;But the mind is no’ to be wyled wi’ meatWi’ a gentleman like me.Thae ither folk, they court their joesAt gloamin’ on the lea;But they’re made of a commoner clay, I suppose,Than a gentleman like me.Thae ither folk, for richt or wrang,They suffer, bleed, or dee;But a’ thir things are an emp’y sangTo a gentleman like me.It’s a different thing that I demand,Tho’ humble as can be —A statement fair in my Maker’s handTo a gentleman like me:A clear account writ fair an’ broad,An’ a plain apologie;Or the deevil a ceevil word to GodFrom a gentleman like me.X

THEIR LAUREATE TO AN ACADEMY CLASS DINNER CLUB