Полная версия

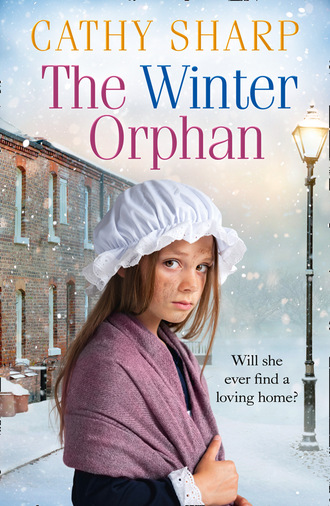

The Winter Orphan

THE WINTER ORPHAN

Cathy Sharp

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photograph © Lee Avison/Arcangel Images

Cathy Sharp asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008286712

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008363987

Version: 2019-08-06

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Cathy Sharp

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Snow was falling, coating trees, bushes and fields with a thick covering of soft, cold whiteness. From the landing window of what had once been an impressive family home and was now the local workhouse, a young girl of perhaps eleven summers watched the heart-wrenching scene as the young mother begged for help in the drive below and tears stung the child’s eyes. She had heard the story of how she herself was found on the steps of the rectory on such a night. Had her mother also begged for entry here and been turned away to die in the bitter cold?

‘Give me back my child,’ the young woman below wept as she was thrust out of the huge wrought-iron gates of the workhouse. ‘I know my babe lived, for I heard her cries!’

‘She died an instant after drawing breath,’ was the reply from the hard-faced warden, who had ordered her ejected from the property. ‘Your child died, Jane! Accept it as the will of God and be gone. If you dare to come here again I shall have you whipped.’ Dressed in black, her thin features showed no hint of sympathy or concern as she ordered the servants to shut and lock those formidable gates.

‘You are a wicked, evil woman!’ the wretched mother cried. ‘I know not my name, but it was not Jane – and I swear that my child lives. I feel it in here.’ She placed her hands to her left breast, tears running down her pale cheeks. It was but a few days since she’d given birth in great pain, her strength almost gone, but even so she knew she had heard a strong cry from a living child and the words of the midwife who had birthed the babe and from somewhere she’d summoned the will to live. ‘I know my child did not die and I know she was healthy for I heard them say that she was beautiful!’

‘The babe is dead to you,’ the spiteful voice said. ‘You are a whore and you do not deserve a child. If you ply your trade once more no doubt you will bear another …’

The gates shut with a clanging sound that was like a death knell to the unhappy woman who pressed herself against them, desperately looking at the grey walls and stout door. She’d struggled here in a raging storm to give birth in safety. Would to God that she had given birth under a hedgerow for her child might then be here in her arms!

It had begun to snow harder now and the wind was cold, biting through her ragged gown and thin shawl. Her feet were bare and felt frozen as she stubbornly stood staring at the door of the workhouse, which remained firmly shut. They had stolen her babe! Jane might not know her true name, for when she’d arrived at the isolated workhouse – ill, close to starving and near to giving birth – all her memories had gone. She knew not where she had been, nor where she was trying to go. Her own name, as well as that of her child’s father, had vanished from her mind with all the rest.

The women who cared for the sick in the workhouse infirmary had named her Jane. She had heard them talking when they thought she was dying. For some reason they were triumphant that the babe was healthy and spoke of someone being pleased that she was such a beautiful girl – but Jane had not died and when she finally began to look about her and ask for her child, they told her the babe had been all but stillborn.

Jane knew it was a lie. She would never believe that her babe had died soon after it drew breath, but if she stood here from now to kingdom come she knew they would not tell her what had happened to her child. Tears ran silently down her cheeks as she turned away. Night was closing fast and the snow was beginning to lie thickly. She was a mile from the nearest village and she knew that even if she reached it no one would help her; they would merely send her here. She was a vagrant. Nothing. No one. If she died this night it mattered not, but if she lived she would return and somehow she would have justice for what had been done here.

As she lingered at the gates, a young girl came rushing from the rear of the house. Jane knew her, for this girl had helped her in the infirmary, had given her a cup of milk and a piece of bread when she lay weeping after they’d told her that her babe was dead.

‘Thank you, child,’ Jane had whispered, because something in the girl’s face had touched her heart – and there was such sadness in those big brown eyes.

‘I am called Bella,’ the girl had whispered to her then. ‘They will beat me if they find me giving you sustenance, because you have angered the mistress …’ She’d gone quickly, afraid of being caught and punished.

Bella was dressed now in just her nightgown and a shawl, shivering with cold.

‘What are you doing here, child?’ Jane said. ‘You will catch your death on this terrible night.’

‘I had to tell you,’ Bella gasped. ‘I saw you from the window and I got out the back way! Don’t believe them when they say your babe died. She lived for I saw them take her out to the gates some two days later and give her to someone in a carriage. You were still ill and would not have heard her even if she cried, but I did.’

‘You saw it? You saw them give my child to someone?’ Jane clutched at the child’s arm, hope soaring. ‘Did you see her, Bella? Do you know if she lived?’

‘She did not die as they told you. Your babe was crying as they carried her away. I heard her and I saw them give her to someone in a carriage – but I am sorry, I do not know who it was.’

‘Thank you!’ Jane reached through the bars of the locked gate to catch Bella’s hands. ‘Go quickly before they discover you or you will be punished.’

The child had been going to say more but she nodded and, giving a little sob of fear, Bella fled the way she had come. Jane’s eyes filled with tears but her heart grew stronger. She had not imagined those cries. Her daughter lived somewhere and one day she would find her and take her back …

Raising her hand, Jane waved to Bella as she paused at the corner of the house, before disappearing round the corner. If she found her child perhaps she might come back and take Bella away from this terrible place … but for the moment it would take all her strength just to survive.

Once inside the scullery, Bella paused, listening for sounds, but the other inmates were in their beds and she knew she must hurry – if the mistress discovered her here at this hour she would be accused of stealing food from the kitchen and beaten. Her eyes stung with tears for she could not forget the look of despair in Jane’s eyes. There was nowhere the young woman would find proper shelter on such a night, for even the church was locked during the hours of darkness to deter those who would steal from God and the poor. It was likely that Jane would die unless she found a barn or a haystack to crawl inside. Bella shivered, feeling chilled, for there was little hope that Jane would recover her babe even if she survived the night.

‘God grant you peace,’ she prayed, knowing that Jane’s chances of survival were as small as Bella’s of finding happiness in this life. ‘If there is a God I think you need him this night …’

CHAPTER 1

On the lonely road, a carriage bowled smartly through the gathering gloom of a bitter night, both coachman and horses eager to find an inn, stables and warmth. Inside, the man, his eyes closed as he endured the jolting of his well-sprung vehicle, let out a cry of pain, but it was not for physical discomfort. In his mind, he had seen again the dying agony of the woman he loved, cradled in his arms but beyond his help.

‘Katharine …’ he murmured, tears on his cheeks. ‘Katharine, why did you leave me?’

Yet it was not her fault that she now lay in the icy ground. The brute who had killed her was punished but that did not ease Arthur Stoneham’s grief. It was for her memory that he was set upon this road this dread night, because she would not let him rest and he knew he would carry this agony until he had fulfilled his promise to her – a promise to find the sister she had loved.

After weeks of following clues that led nowhere, Arthur was no closer to discovering what had happened to Marianne Ross more than twelve years earlier than he had been when he left London. He had visited the man Katharine Ross had spoken of in her dying fever. Squire Thomas Redfern had seemed a pompous young man to Arthur and uninterested in Katharine or her sister and so he had simply told him of Katharine’s death and her wish that Arthur would look for her sister.

‘It is my intention to do all I can to find Marianne,’ Arthur told the squire, looking for some flicker of feeling but there was none.

‘I do not believe you will find any trace of that unfortunate young woman,’ Thomas said in a voice devoid of emotion. Married, with two young sons, he had clearly ceased to mourn her long ago. ‘A search was made at the time. Marianne unwisely walked home through the woods, though she had been warned gypsies were camping there. My father and hers made searches but no word of her was ever heard. I think she was murdered and her body concealed …’

For a moment there was a flicker of something but then it was gone. If this man had ever loved Katharine or her sister, he had only a fleeting interest now. Arthur decided that he must have mistaken Katharine’s last words; she could not have loved someone as unfeeling as this man! He would not give him another thought, nor, if Marianne were found, would he pass on news of her to such an unfeeling oaf.

The resolution helped to soothe his wounded heart a little, for he could not be jealous of such a man. Katharine must have been trying to say something other than the words that had burned into Arthur’s soul: ‘Tell Tom I loved him …’

He would not think of this man as a rival for Katharine’s love again. Perhaps she had meant to say, ‘Tell Arthur I loved him,’ and the words had come out wrong.

The squire had no clues to help Arthur find Marianne Ross, nor did any others he questioned in the household. It was no different in the village. No one remembered much of the old tragedy. Marianne had simply disappeared that night and never been heard of since. Most who remembered the old story believed her dead. Arthur himself thought it was the most likely explanation, but he would do his best to exhaust any leads that might help him to discover the truth, though they were few indeed. Gypsies had been in the woods and one of Marianne’s shoes had been found so it seemed to him that there were two possible explanations: either Marianne had been attacked and killed or she’d been abducted by the gypsies. He was unlikely to find her whatever the case, but he must exhaust all possibilities before admitting failure for his own peace of mind.

Arthur lounged back against the comfortable squabs in his carriage, closing his eyes as his coachman drove through the icy night. Although his journey had been fruitless, he was still in Hampshire and not ready to return to London and give up the search for Katharine’s lost sister. As Hetty, his true friend and colleague, had told him, he owed it to the memory of the woman he’d loved. Hetty ran Arthur’s refuges for women and children in London and had been Katharine’s friend, nursing her when she lay dying.

Katharine’s tragic death was still like a stone in Arthur’s breast and he could not face the anxious looks and concern of his friends, especially those who had also loved her. The man who had caused her death was locked away in a cold cell from which he would emerge only to meet death at the end of the hangman’s rope. The rogue’s fate was assured, but that did not ease Arthur’s state of mind. His grief was too bitter, too personal, to be shared – nor did he wish for sympathy, and together with the grief came the doubts and the guilt.

Was it Arthur’s fault that Sir Roger Beamish had seized the chance to send his beautiful Katharine to her death in front of that brewer’s waggon? Sir Roger’s insane jealousy was certainly one cause for the spiteful act, but Arthur now knew that the man had been ruined, his fortune lost, and that in his twisted mind he’d blamed Arthur, who’d caught him cheating and accused him publicly of it, for his downfall. Or was it because Katharine had refused him and accepted Arthur’s proposal that he’d given her the vicious push that ended her life beneath the flailing hooves of the heavy horses? Arthur knew he would never discover the answers to his questions and it haunted him.

He groaned and pushed his tortured thoughts to a distant corner of his mind. Katharine was lost to him and nothing would bring her back. His only hope of finding peace was to unravel the mystery of her sister’s disappearance. Perhaps then he might be able to sleep at night.

Suddenly, he heard a shout and his carriage was brought to a screeching halt as the coachman reined in his horses abruptly and Arthur was flung from one side of the carriage to the other. By some miracle, his man managed to hold the plunging, screaming horses and the coach did not overturn. Recovering swiftly, Arthur wrenched open the door and jumped out into the road.

‘What happened?’ he demanded of his driver, but even as he asked, Arthur saw what looked like a huddle of rags lying a few feet in front of his carriage. The horses were still snorting and stamping their feet, disturbed by being so misused, their breath white on the frosty air, and Arthur went to their heads to quieten them, whispering against their faces so that they calmed and responded to his voice before he walked on to investigate the bundle.

Arthur looked to either side of the road suspiciously for it might be a trick to take them unawares. Some thirty-odd years earlier, highwaymen had been the plague of these roads, but none had been seen since the last known gang was caught many years before. It was now 1883 and Arthur did not fear them but there were still rogues and thieves aplenty who might offer violence on a dark lonely road such as this, so it was best to be careful. Indeed, it was only the previous year that Her Majesty Queen Victoria had been shot at, so Arthur went prepared wherever he travelled. He patted the pistol in his greatcoat pocket, ready for the worst if this was a trick.

‘Be careful, sir,’ his groom warned. ‘It may be the work of rogues …’

Arthur had reached the huddle of rags and saw at once that it was a young woman lying there. Her face was pale and for a moment he thought her dead. Kneeling on the frozen surface of the road, Arthur felt for a pulse. It was faint but it was there. He swept her up in his arms as his groom came to join him.

‘What is it, sir?’

‘A young woman – and she’s barely alive, Kent. Had we not chanced on her she might have died this night. We need to get to the nearest inn.’

‘There’s a small one about a mile ahead. Let me help you, sir.’

‘Open the door of the carriage,’ Arthur said. ‘I have some brandy in my bag and I’ll see if I can get her to swallow a little. As soon as we reach the inn, I want you to discover the nearest doctor and bring him to us.’

Kent nodded, glancing at the woman as Arthur lifted her gently on to the seats and sat next to her, holding her against him. Another servant might have observed that she was a vagrant and warned his master, but all Arthur’s people knew that such a remark would earn them a severe glance. Arthur Stoneham would never leave a woman to die on the side of the road, even if, as it looked, she was a beggar.

‘Yes, sir,’ he said. ‘I’ll tell the coachman to get on now.’

He shut the door carefully and left Arthur to settle the unfortunate woman. Arthur took a small silver flask from his pocket and opened the stopper, then gently lifted the woman in his arms so that she was propped up against his shoulder as he put the flask to her lips.

‘Try to swallow a little please,’ he said gently. ‘It will warm you …’

Whether she heard or not, Arthur could not know, but she moaned slightly and, as her mouth opened, he poured a tiny drop on to her tongue. Her throat swallowed and he poured a few drops more. He thought she sighed and her body seemed to sag against him. He sat with his arms about her, holding his greatcoat around her frail body, instilling his warmth and vitality into her, willing her to live.

‘Be brave, lady,’ he murmured. ‘I have you and you are safe now.’

As the coach slowed to a halt and his groom opened the door and helped him ease the woman out, he saw a small inn with a lantern above its door and welcoming lights from a parlour window.

‘Run and secure rooms for us, Kent – and then fetch that doctor!’

‘Yes, sir.’

Kent ran ahead while Arthur gave instructions to his coachman about stabling the horses then assisted the shivering woman to walk. By the time he reached the lights and warmth of the inn hallway, Kent had secured a room for him and accommodation for himself and the coachman.

‘There is but the one room in the house but I thought it would do as you will want to watch over the young lady, sir – and me and Barrett are over the stables and the landlord has given me the doctor’s direction,’ Kent told him.

Arthur nodded to the landlord. ‘I shall require a fire lighting and food for us all. My companion is not well, so some warm milk, perhaps, if the doctor thinks it advisable.’

‘Yes, Mr Stoneham.’ The landlord bowed respectfully. Kent had made sure to speak of his master’s consequence, no doubt, for the landlord took a brass oil lamp and lit their way up to a large chamber at the rear of the house. ‘I fear there is but the one bed, sir.’

‘She is ill and must have it,’ Arthur said. ‘I shall take the chair and be comfortable enough; besides, she will need watching. I do not know what has befallen this poor girl, but I shall not let her die if I may prevent it.’

‘Your man said you were a philanthropist of the highest order, sir. My wife would take in all the waifs and strays if she could …’ He tutted as he saw the condition of the young woman. ‘She cannot be past twenty, sir. It is sad to see one so fair brought to this.’

‘Yes, you are right,’ Arthur agreed. ‘I fear it happens all too often but, with God’s aid, we help those we can.’ The landlord nodded and looked pious.

‘Amen to that, sir,’ he said. ‘I’ll send the chambermaid up to light the fire straight away.’ He paused, then, ‘Will you dine here or in the parlour?’

‘I’ll dine after the physician has been and we hear what he has to say.’

The host nodded and left Arthur to place the girl between the clean sheets and cover her. Despite her wretched clothes, he thought she had washed recently and her skin had a pleasant perfume of its own. She was pretty, he decided, as he pushed the long fair hair back from her cheek. If she lived, he would be interested to hear her story and would help her if she was willing to be helped. He could take her to Hetty, who would find her a bed at the refuge and perhaps a place to work, he thought as he turned away to take off his coat.

‘My baby! Give me back my baby!’

The cry from the young woman’s lips was so desperate that Arthur turned sharply and saw that she was sitting up in bed staring about her wildly.

‘Where is she? What have you done with her?’

‘I saw no baby …’ Arthur felt a stab of doubt. Had he missed the child? He had seen nothing of it when they rescued the woman. No, there had been no child nearby that he’d been aware of – but had it been lying hidden by the side of the road? ‘Forgive me, where was your child, madam?’

‘They took her. They said she was stillborn but I heard her cries,’ the woman said clearly, in the voice of one gently reared, and then fell back against the pillows, her eyes closing.

Arthur bent over her, fearing for a moment that a relapse had taken her life, but she was sleeping now and her breathing seemed a little easier. He was relieved, but the poor girl was feverish. He decided that he would not go and look for the missing babe for she seemed confused. Perhaps she had recently given birth to a child that had died, which might explain her distress, but why had she been lying in the middle of the road?

It was more than half an hour before Kent returned with the doctor. By that time the maid had a good fire burning and the room was pleasantly warm. The doctor examined his patient and confirmed Arthur’s belief that she had recently given birth.

‘She still has her milk,’ he told Arthur, ‘though I would say it was some days since the birth – perhaps more than a week.’

‘She was asking for the child and seemed confused. Do you think she has been attacked?’

‘I see little wrong with her,’ the doctor told Arthur. ‘I imagine she may not have eaten for some hours and she was probably on the verge of dying of the cold. It is a bitter night, Mr Stoneham – too cold for any of us to be out.’

He seemed a little annoyed that he had been brought from his warm house to tend a woman he did not consider sick, for bearing a child was the law of nature. Arthur kept his counsel, paid him generously and thanked him for his advice – which was that she should have rest, good food and be kept warm.

‘She is young and with some food inside her will soon recover her strength, sir. I think these young women are often back in the fields within days of giving birth.’

‘You think her a country woman?’

‘She is dressed like one of the travelling folk,’ the doctor said disparagingly. ‘Be careful, Mr Stoneham – these people can take advantage if you let them.’