Полная версия

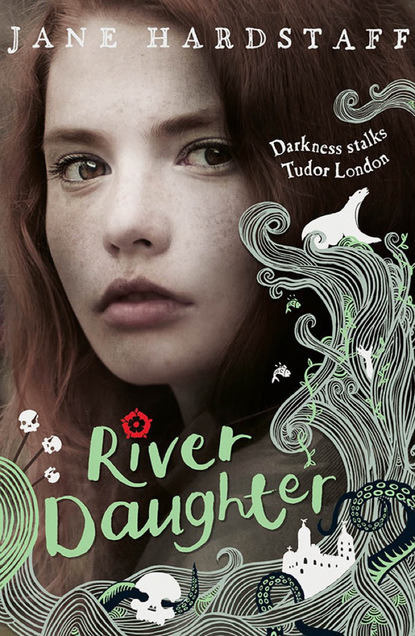

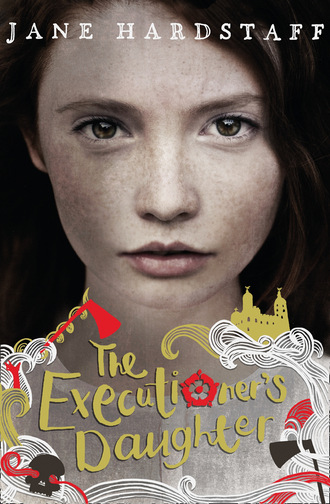

The Executioner's Daughter

First published in Great Britain 2014

by Egmont UK Limited, The Yellow Building,

1 Nicholas Road, London W11 4AN

Text copyright © 2014 Jane Hardstaff

Chapter illustrations © 2014 Joe McLaren

The moral rights of the author and illustrator have been asserted

First e-book edition 2013

ISBN 978 1 4052 6828 8

eISBN 978 1 7803 1388 7

www.egmont.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont cannot take responsibility for any third party content or advertising. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

For Mum and Dad

CONTENTS

Cover

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

1 Basket Girl

2 The Prisoner

3 The Song of the River

4 Escape

5 River Thief

6 Two-Bellies’ Revenge

7 The Queen’s Uncle

8 Keeping a Secret

9 A Hand in the Darkness

10 The Ragged Man

11 Truth and Lies

12 Leaving

13 Salter

14 Bread First Then Morals

15 Frost Fair

16 Salter’s Scam

17 Ice River Ride

18 Dragon’s Heart

19 The Queen and the Little Swan

20 The Riverwitch

21 Snatcher on the Shore

22 Ghosts in the Walls

23 A Trick

24 Drowning

25 The Great Wave

26 Friends

27 Bluebell Woods

A note from the author

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

Basket Girl

She’d never get used to beheadings. No matter what Pa said.

Peering through the arrow-slit window, Moss tried to catch a glimpse of the fields beyond Tower Hill. All she could see were people. Crazy people. Spilling out of the city. Scrabbling up the hill for the best view of the scaffold. Laughing and shouting and fighting. Madder than a sack of badgers. She could hear their cries, carried high on the wind, all the way up to the Tower.

‘Get your stinking carcass off my spot!’

‘Son-of-a-pikestaff, I ain’t goin nowhere!’

‘What are you? Dumb as a stump? Move your bum, I said! I’ve been camping here all night!’

‘Then camp on this, coloppe-breath!’

She shook her head in disgust. Execution Days brought a frenzied crowd to Tower Hill. The more they got, the more they wanted. Like a dog with worms.

Of course, London had always been execution-mad. If there was a monk to be drawn and quartered or a Catholic to be burned, the people liked nothing better than to stand around and watch. Preferably while eating a pie. But you couldn’t beat a good beheading. That’s what the Tower folk said. Up on the scaffold was someone rich. Someone important. Maybe even a Royal. That’s what people came for. Royal blood. Blood that glittered as it sprayed the crowd. It made Moss feel sick just thinking about it.

‘Moss!’

Pa was calling. She could hear his cries below, faint among the bustle on Tower Green.

‘Moss, MOSS!’

He’d be panicking by now. Well, let him panic. She’d sit tight. She’d wait. With luck, he wouldn’t find her. Judging by the rats’ nest in the fireplace, no one had used this turret for months. No prisoners, no guards and no one to find a girl somewhere she shouldn’t be.

Moss scraped her tangle-hair out of the way and pushed her freckle-face to the narrow gap. Up here, she was ten trees tall. She could see everything. On one side Tower Hill. On the other the river. And, in between, the Tower of London, planted like a giant’s fist in the middle of a deep moat, lookouts knuckled on all corners. It was said that the Tower was strong enough to keep out a thousand armies. Bounded by two massive walls, it guarded the city, arrow-slit eyes trained on the river. It was a fortress, a castle and a prison. Moss had lived here all her life. And in the summer the reek of the moat made it stink like a dead dog’s guts.

‘Moss!’

Pa’s voice was closer.

‘MOSS!’

Too late she heard his feet pounding up the twist of steps. Now there was no way out. She scowled and scrunched herself into a corner.

‘Are you up there?’

‘No! Go away!’

His face appeared in the doorway, full of frown.

‘What are you playing at? Don’t do this to me, Moss.’

‘I’m not doing anything.’

‘You know what day it is. Come on. It’s time.’ He stood over Moss, his bear-like frame blocking the light.

What choice did she have? She dragged herself to her feet and followed him down the winding staircase, all the way to the ground. The basket was waiting for her at the foot of the steps.

‘Take it and get behind me.’ Pa thrust the basket into her arms and picked up his axe.

A blast of trumpets screeched from the high walls. Everyone stopped what they were doing. The Armoury door yawned wide; two hundred soldiers poured out and marched across the courtyard to the gates.

Pa pulled the black hood over his face. Moss knew what was coming. All around them, people shrank back. Some shuddered, some crossed themselves. Some turned their heads as though a foul stench pricked their noses. Moss could have cried with shame. But what good would that do? So she stared at her boots, trying to shut out the whispers.

Stay back . . . The Executioner . . . the basket girl . . . don’t go near them. They touch death.

‘Come on,’ said Pa and yanked her into the march of the procession.

Over the walls of the Lion Tower came the howl of animals in the Beast House. Moss had never seen the beasts, but their roars echoed over Tower Green every time the bell was rung, or the cannons fired, or on a day like today when the shouts from the hill stirred them in their cages.

The procession marched on. Over the narrow moatbridge to the great gate. Once more the fanfare blasted from the turrets and the portcullis was raised. Moss was knocked back by the roar of the crowd. She dropped her basket, covering her ears.

‘Pick it up,’ said Pa. His voice was flat.

‘Pa, all these people . . . there must be twice as many as last time.’

‘Just walk.’

She walked, following the slow line of soldiers up the muddy path of Tower Hill. All around her the crowd heaved and pushed, and those that weren’t complaining cried out their business.

‘Carvings, carvings. Last true likeness of a condemned man!’

‘Tragic Tom on a tankard! A little piece of history to take home!’

‘Ladies and gents! The Ballad of Poor Sir Tom! Cry like a baby or yer money back!’

Moss hurried on beside Pa. They were nearly at the top of the hill. And though the crowd pressed her from all sides, she caught a glimpse of the sprawling city beyond. It was smoke and shadows, dark as a cellar. A mystery. A place she would never go. Her world was the Tower. And the only time she set foot outside its walls was the slow walk to the scaffold on Execution Days.

She glanced across at Pa. His hooded head was bowed, just like always. His axe held respectfully by his side, just like always. And, just like always, it made Moss cringe.

‘Out of the way, you wretches!’ Soldiers were shoving the front row, who shoved viciously back. ‘Make way for the Lord Lieutenant of the Tower!’

Lieutenant William Kingston. Doublet drawn tight round his girdled waist, chest puffed, savouring every step of his slow walk up the hill. He was a man with an eye to a title. That’s what people said. In the space of a month, he had organised the executions of three monks and a bishop. It seemed to Moss as though the whole of London flocked to the hill. To see the monks dragged to Tyburn. To see Bishop Fisher’s head roll. And today the beheading of the man who was once the King’s best friend. Sir Thomas More. No wonder people were calling it ‘the Bloody Summer’.

She felt the crowd surge forward and she struggled to stay in line while the soldiers pushed them back. The Lieutenant bowed low. His guests had arrived, sweeping towards the bank of seats by the scaffold. There was the tight-lipped man who came to every execution. Next to him another man, straight-nosed, eyes like stones. In front of them both was a lady, her face hidden, shrouded in a cloak of deep blue velvet. And now whispers were stirring in the crowd.

The Queen . . . Queen Anne Boleyn is watching . . .

Anne Boleyn. The Firecracker Queen. She’d come from nowhere. Dazzled the King and blown a country apart. People didn’t like her, Moss knew that. She’d stayed in the Tower once. The night before her coronation. And though Moss hadn’t seen the Queen herself, she’d heard plenty of tongues clacking. They said that her clothes were too showy. Her manners too French. That she was an upstart who didn’t know her place.

Moss took a good look. Was that really her? The velvet cloak, too heavy for summer, weighed down her small frame. She didn’t look much like a firecracker, thought Moss. More like a broken twig. Her movements seemed fragile. Hiding under the shadow of her cloak, her face was anxious. And when the stone-eyed man said something in her ear, she flinched.

Now the drum was beating. The Yeomen were coming. Forcing their way up the path to the hill, bright in their red and yellow livery.

Moss peered round Pa to get a better look. The Yeomen were bunched in a tight wall around the prisoner, but there he was. Slow as an old bull in the July heat. Sir Thomas More was a good man, people said. A devout man. But King Henry the Eighth had no time for goodness or devotion if it didn’t get him what he wanted. And Moss wondered at how quickly the King’s best friend could become his bitterest enemy, with all of London jostling for a glimpse of his death.

In the Tower the bell began to toll. Moss clutched her basket.

It was time.

All around her the crowd was pressing.

On the scaffold Pa was waiting.

Sir Thomas climbed the steps, his white cotton gown laced loosely about his neck. White so the blood would show. And at that moment, Moss wished so desperately that Pa would lay down his axe. Punch a soldier. Leap off the scaffold, grab her and dive into the crowd. Let them take their chances in one glorious dash for freedom.

She drilled her gaze at Pa.

He wasn’t going anywhere. That was obvious.

She saw his eyes flicker through the slits in his hood and there was a cheer as he took out the blindfold. She watched Sir Thomas push a pouch of coins into his hands. It was the custom of course, but she hated that Pa took it. Money for a good death. Make it quick. Make it painless. Pay and pray.

She fixed her eyes on the straw. Spread in a wide arc around the block, it would soon be soaking in wine-dark blood. Behind her the crowd hushed, looking on hungrily as Sir Thomas let Pa guide his neck into position.

The hill held its breath.

Pa raised his axe.

With a single blow, it hit the block. Clean. Just like always.

The crowd exhaled. From inside the Tower a cannon fired and a cloud of white doves fluttered over the turrets, their heads dyed red. Everyone gasped. It was all Moss could do to stop herself throwing up.

On the scaffold Pa stood over the slumped body of Sir Thomas, wiping his axe on the sack. That was her cue.

She thumped the basket on the ground. The Lieutenant plucked Sir Thomas’s dripping head from the straw and lobbed it over the edge of the scaffold, where it landed with a whack in the basket. The crowd went wild.

Moss picked up the basket. Pa was by her side now. She couldn’t look at him. Instead she concentrated on getting down the hill without stumbling. She was glad of the distraction and tried not to notice Sir Thomas’s unmoving eyes, rolled forever to the sky.

CHAPTER TWO

The Prisoner

‘I’m not touching that thing, so don’t even bother to ask!’

‘Leave the axe then, just help me with the broadswords –’

But Moss wasn’t listening. She clomped out of the forge, slammed the door and kicked the water bucket hard, sending a spray of drops into the bitter morning air. It was freezing. Even for January. Fog every night, frost every morning, with a chill that Moss couldn’t shake from her bones.

Six months had passed since the beheading of Sir Thomas. A bloody summer, a miserable autumn and a long, cold winter that wasn’t over yet.

It was barely dawn, but already the people of the Tower were up and busy. Stable lads were trundling oat barrels over the courtyard and kitchen girls bickered as they carried breakfast to the Lieutenant’s Lodgings. From the open shutter behind her came the rasp of bellows, breathing life into the fire. When he wasn’t chopping heads on the hill, Pa worked as Tower blacksmith. The little stone forge where they lived was set apart from the bigger buildings of the Tower. Huddled against the East Wall like a cornered mouse, it had been Moss’s home for as long as she could remember.

‘Moss! Come inside! Now!’

She shivered. A fog was rolling in from the river, curling over the high walls, fingers poking through the cold stone turrets. Tower folk crossed themselves when the river fog came. It was a silent creeper. A hider. A veil for the unseen things. Things that might crawl from the water. From the black moat, or from the swirling river that slipped and slid its way through London, treacherous as a snake. But whatever it was that made them afraid, it had never shown itself to Moss. The fog didn’t scare her.

‘Moss!’

She gave the bucket another kick.

‘Will you come in?’

She sighed and dragged herself back through the forge door. Inside, Pa was polishing the axe.

‘Bread and cheese for you on the table.’

‘I’m not hungry.’

Pa turned the axe, rubbing oil into the blade. It was his little ritual and he did it every morning.

‘When there’s food on the table, you should eat.’

Moss said nothing. What was there to say? This was her life and she just had to accept it. Pa was the Tower Executioner. She was his helper. They were prisoners and this was pretty much it, because they were never getting out. She’d asked Pa a thousand times how they’d ended up in the Tower. Each time she got the same gruff reply. Pa had been a blacksmith. And then a soldier. Accused of killing a man in his regiment, he and Ma had gone on the run. They’d hidden in a river, where the shock of the icy water sent Ma into labour.

‘If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I would never have believed it,’ Pa had said. ‘It was a miracle. You swam from your mother until your fingers broke the surface. Then you held on to me with those fierce little fists. And I didn’t let go.’

Of course, the soldiers got Pa in the end. And he would have been executed there and then had it not been for his captain. Pa was the captain’s finest swordsman. His kills were clean and accurate. And rather than waste such a talent, the captain wanted to put it to good use. For he was William Kingston, the new Lieutenant of the Tower of London. And he wanted Pa to be his Executioner.

That was all Pa would say. Every time Moss begged him to tell her more, he clammed up. ‘Your mother died on the day you were born. We’re prisoners now. End of story.’

But how could it be the end, thought Moss? Out there was a river and a city. Beyond that were fields. And beyond the fields were places she could only dream about. Places she would go one day.

She stared at Pa, and coiled the end of one of her tangle-curls round her finger. Rub rub. His knuckles were white, working the axe blade to a blinding shine. There was less than a week to go until he’d use that axe again. Moss felt her stomach sink to her boots. She wished she were anywhere but here.

‘Armourer’s keeping us busy today,’ said Pa. ‘Longswords and broadswords. Two boxes. Rusted and broken. Need to get that fire really hot. More wood from the pile . . .’ He stopped. There was a boy standing in the doorway. Moss had seen him before. He worked in the kitchens.

‘What do you want?’ said Pa gruffly.

‘Cook says she’s short-handed. Needs an extra body to fetch and carry fer the prisoners. Says to bring the basket girl.’

Pa hesitated. ‘We’re busy in here today.’

The boy cocked his head to one side. ‘You ever seen Mrs Peak angry? Got a temper hot as a bunch of burnin faggots. If she says bring the basket girl, that’s what I’m doin.’

‘Well, it’s not a good time –’

‘Forget it, Pa, I’m going,’ said Moss. Anything was better than being stuck in the forge with a father who chopped off heads. She was out of the door before he could stop her.

‘Frost is here! Ice is coming! And devil knows what crawling from the river! Close that door, you little scrag-end!’

Moss was quick enough to duck the blow from Mrs Peak’s fist.

‘Well, what are you waiting for? Christmas? Take this soup up to the Abbot and be quick about it or I’ll cut off yer ears and boil them for stock!’

Moss looked around eagerly. She’d never set foot in the kitchen before. Never spoken to a cook or a spit boy. Never carried a meal across the courtyard. But this was a chance, wasn’t it? To be one of them? A kitchen girl. Not a basket girl.

A bowl of steaming broth stood on a table near the fireplace. She reached for it and felt a sudden sting on her cheek.

‘Ow!’

A dob of hot apple dropped to the floor. On the other side of the table a kitchen girl licked her fingers, shooting Moss a scornful glance while another one sniggered behind her apron.

Moss wiped her burning cheek and turned away from the girls. Maybe fitting in wasn’t going to be so easy. She picked up the bowl of soup, then ducked as the lumpen fist of the Cook swung over her head once more. It clipped the spit boy in a puff of flour.

‘What was that for?’ he wailed, dropping his pail of water.

Mrs Peak clouted him again. ‘One for the basket girl and another for all this mess!’ The tide of water from the spit boy’s pail slopped against the table legs, sending the kitchen girls into a spasm of giggles.

‘Hell’s bells!’ bellowed Mrs Peak. ‘I’m surrounded by idiots! Lazy girls and halfwit boys! I’d get more help from a bag of mice!’

Moss walked slowly to the kitchen door, balancing the bowl as carefully as she could. She felt another hot slap on her shoulder.

Basket girl. Bloodstained girl. Filthy little basket girl.

Basket girl, when you’re dead, who will carry all the heads?

The chants of the girls rang after her down the corridor. She felt a sob rise from her chest and swallowed it back down. She would not cry.

It wasn’t easy carrying a bowl of soup, slip-sliding across Tower Green. In winter, the looming walls shut out every sliver of sunlight, turning the grass to mud. Her fingers clutched the warm bowl. There was a little less soup in it now and she hoped the Abbot would not be angry.

Moss had seen them bring the Abbot in a boat from the river through Traitors’ Gate, two months back. He’d wobbled when the soldiers hauled him to his feet. Maybe he’d never been in a boat before, thought Moss. Or maybe he was afraid. Behind him, the barred gate swung shut, jaws closing. The black water of the moat flickered with burning torches. Few who came through Traitors’ Gate ever made it back out. The Tower was a place of death.

Moss stood outside the Lieutenant’s Lodgings. In front of her two guards blocked her path, halberds crossed. This was the only way in to the Bell Tower. They’d put the Abbot right at the top in Sir Thomas’s old cell.

She hesitated. ‘Soup for the Abbot’s breakfast?’ she said, half expecting them to send her straight back to the forge with a clipped ear. But they let her pass. A wood-panelled corridor gave way to a narrow stone arch and a set of stone steps. Moss climbed, twisting up and up to a half-landing where another guard stood outside an oak door.

‘Soup for the Abbot?’ said Moss.

The guard unlocked the door. Moss gripped the bowl and stepped in.

The Abbot was on his knees, mumbling a prayer. In front of him was an empty fireplace. Wood had been scarce this winter and unless a prisoner could pay, his hearth stayed cold.

‘Frost is upon us,’ said the Abbot, without turning. ‘Frost, then ice. A real winter. Cold as the coldest I have known.’

He lifted his head. Straggling hair framed his face and his shaved crown sprouted wild tufts. Two months in a cell didn’t always turn you into a crazy man, but it made you look like one, thought Moss.

Moss offered the bowl and the Abbot motioned to a small table.

‘Soup?’ he said.

‘Yes,’ said Moss, ‘I . . . I carried it as best I could. But the mud and . . . I spilt some. I’m sorry.’

The Abbot wrinkled his eyes at Moss. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘I do believe you are.’

He creaked off his knees and hobbled to a chair by the table. Moss hovered by the door, unsure whether to go or wait for him to finish. The Abbot slurped the soup, his lips trembling a little each time he raised the wooden spoon to his mouth.

‘Well, I’ll say this,’ he said. ‘Even lukewarm, this is tasty soup. Better than I’d be getting back in the Abbey.’ He slurped some more. ‘And I’m used to silence of course. A cold room, a hard pallet; all part of a monk’s life. There’s one thing I do miss though.’ He put down the spoon, picked up the bowl and put it to his lips, draining the last of the soup. ‘Would you like to know what?’