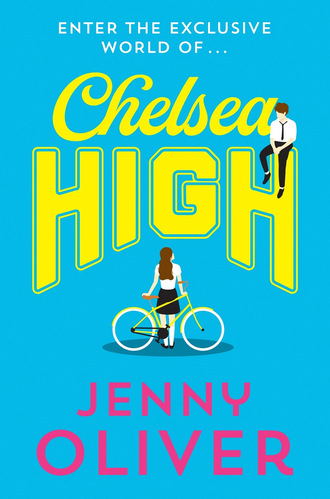

Chelsea High

First published in Great Britain 2020

by Egmont UK Limited

2 Minster Court, 10th floor, London EC3R 7BB

Text copyright © 2020 Jenny Oliver

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

ISBN 978 1 4052 9504 8

Ebook ISBN 978 1 4052 9505 5

www.egmont.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Stay safe online. Any website addresses listed in this book are correct at the time of going to print. However, Egmont is not responsible for content hosted by third parties. Please be aware that online content can be subject to change and websites can contain content that is unsuitable for children. We advise that all children are supervised when using the internet.

Egmont takes its responsibility to the planet and its inhabitants very seriously. We aim to use papers from well-managed forests run by responsible suppliers.

For KY, SW & LG

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CHELSEA HIGH 2

CHAPTER ONE

Back series promotional page

CHAPTER ONE

I stopped so suddenly, I nearly got hit by a taxi. The cabbie honked his horn, swerving to avoid my bike, but I barely noticed. All my attention had been caught by the sight in front of me – the teeming mass of beautiful people lolling on the wide concrete steps of the red-brick building, all in grey and white uniforms, all the same as mine but infinitely better, the chequered flags waving from turrets and the million mullioned windows sparkling through the haze of bus fumes, all stained glass like a church. My heart lurched. Surely this couldn’t be a school. It was a palace. A sightseeing dot on a map for tourists.

My eyes drank it all nervously in. The sun-kissed girls with big toothy grins who were draped like satin over the railings. The boys with their perfect shaggy hair, razor-sharp cheeks and ice-white shirts chucking rugby balls high in the air and laughing at stuff on their phones. My heart beat faster as they seemed to merge into one, a tangle of tanned limbs and glistening skin, posing for back-from-summer photos, shrieking, air-kissing, boys lifting girls into giant twirling hugs. All of them glowing like they’d been dipped in gold.

My every instinct was pulling my handlebars round, urging: go home, go home.

I thought about what would be happening at my old school right now. One of my friends would call a lazy ‘Hi’ as I ambled up the cracked tarmac path, toast in my mouth, hands trying to do something with my hair. On Mulberry Island, we saw each other every day regardless of whether it was school or holidays, so no one had a tan we didn’t know about. No one had new hair, no one shone like gold and the old sixties building looked nothing like a palace.

But this wasn’t my old life. And no one was waiting for me.

A huge black Rolls-Royce purred past me, so close it almost grazed my leg, pulling me back to the present. I felt everyone on the steps pause what they were doing. A chauffeur got out to open the passenger door, and I watched as none other than Coco Summers unfolded herself from the back seat – tall, blonde and impatient. I heard myself gasp. Model, influencer and selfie queen, Coco had maybe two million followers on Instagram, probably more. Her #cocostyle sold out within seconds. I recognised the slouchy silver backpack she’d just slung over her shoulder. I remembered how she once wore a grey woolly hat with a pink bobble that I owned, and then suddenly everyone had it. I was torn between a bubble of pleasure that we shared the same style and annoyance that she’d ruined my hat.

I stared, entranced, as she sauntered up the steps. Even if I hadn’t recognised her, I’d have known she was special. Her caramel hair with its over-long fringe was perfectly, artfully dishevelled, her skin was luminous. She walked like she owned the world, and she had an aura that made it impossible to look away.

From the school steps, a glossy brunette whooped and tottered down the steps to hurl herself into Coco’s arms before a guy with red hair and a deep golden safari tan leaped the bannister and grabbed them both, lifting them up as if they were weightless.

I had a panicked moment of tunnel vision. I couldn’t fit in here. As the Rolls-Royce cruised away, I wanted to jump inside, to drive back in time to the warmth of the island, to my desk with its graffiti carved with a compass, to the register taken by Mrs Wellington who always had a cup of tea and three plain digestives, to the café after school where we drank hot chocolate piled with marshmallows or played basketball with the boys on a court ravaged by tree roots. To a place where no one twirled anyone, no one pouted, no one wore rucksacks worth over a grand to school.

I looked up with a jolt of desperation. The turrets loomed sharp as daggers. I saw the gleaming gold sign above the doors: Chelsea High School, the words Vincere fecit inscribed underneath. And beneath that, for anyone unfamiliar with the Latin: Made to win.

Go home, my rusty old bike seemed to whisper again.

But my home had gone.

CHAPTER TWO

In a bit of a daze, I looked around for somewhere to lock my bike. The chatter from the steps filled the air. I felt like I was in an impenetrable bubble, watching a cinema screen. I self- consciously flattened my hair as I took off my helmet and tried to catch a glimpse of my fringe in the metal of my handlebars to check it wasn’t sticking up all over the place. The bike racks by the school were already full with spanking new Bianchis and other flash racing bikes, so I had to walk away, searching the side streets till I eventually found a spot much further up the road. I had to run back when I heard the bell ring – by which time the school steps were deserted. Everyone had vanished in a click of manicured fingers, leaving pigeons to peck at crisp crumbs and a forgotten school jumper slung on the railing.

I sprinted up the steps to catch the huge wooden doors just as they were closing. And then I stepped inside Chelsea High.

My eyes had to adjust to the darkness. As the fresco ceilings and gilded cornicing came into focus, I felt again like I’d come to the wrong building. This was a cathedral, not a school, and we should be silent in worship. Ahead of me, dark archways and low lighting led down endless empty corridors as doors slammed all around. The smoggy sunlight cast shadows like monsters across the gleaming parquet. I could hear my breath. I could hear my heart.

My old school came to mind again. The patches of damp on the plasterboard ceiling at Mulberry Island Academy, the Sellotaped window-pane cracks, my beloved locker. The railing I swung on to turn the corner every day. The smell of lunch cooking. The meadow with grass so long you could lie down and disappear. Eating Maltesers and talking to Jess about nothing. I would do almost anything to talk about nothing now. What a luxury – that careless boredom.

‘No dawdling. First day of term. Start as you mean to go on.’

A deep voice echoed down the empty corridor.

Instinctively I stood up straighter, hitching my old rucksack higher, starting to walk forward. But I didn’t know which way to go. I was completely lost. I vaguely remembered a map arriving in the post with all the other introductory papers in a brown envelope, but I had no idea where it had ended up. Everything at home now was just a mess of confusion.

I’ve lived on a houseboat all my life, and all my life I’ve loved it: the narrow cosiness, the cocooned security, the gentle lapping of the tangy water in summer and the harsh battering of the rain in winter. But this morning, the sharp rap on our front door had been like a crack splintering the boat’s hull. I watched my dad spill his coffee in his haste to answer the door. It was bad enough that he was dressed so differently today. He’d always been one for a bright shirt and, if he had to, a funny tie. ‘Hook them with a laugh,’ he’d say. This morning he had been wearing a pale yellow shirt, grey tie and suit trousers. Almost as if he was the one going to school.

My mum straightened up, visibly nervous as she said with vague dismissal: ‘Time to go to school, Norah. Quick, off you go.’ She’d put her arm round my shoulders and given me a distracted kiss on the top of my head.

‘I don’t want to go,’ I’d muttered.

But my mum just waved the statement away, her interest diverted by the front door. She moved away from me, and my shoulder felt suddenly empty.

Dad stood to one side to let a humourless man in a dark blue suit pass on the narrow steps, arm stretched out to show him which direction to go. On a houseboat, there is only one direction.

My mum beckoned for him to sit at the small, round table where the remains of our breakfast had been cleared away. She had wiped the table and was now retying the black bow at the end of her plait, looking uncomfortable and fidgety in her long yellow and black patterned skirt, white shirt and bright yellow sandals. Dressed up but trying to look casual.

‘Off you go, Norah,’ she said. Insistent.

I didn’t like the look of our visitor. No one in a suit had ever set foot on our boat. Our visitors usually wore old baggy shirts and carried musical instruments or bottles of home- brewed beer.

‘I’ve got to get my bag,’ I said, watchful and hesitant.

The man in the suit was pulling out one of our mismatched chairs, scraping it on the floor, setting his black briefcase on the table. It wasn’t my imagination that he gave the boat a disparaging once-over.

‘Get a move on, Norah!’

The snap in my mum’s voice surprised me. She’d never shouted at me before in my life. At my old school I would always scrape in just as registration ended. My best friend Jess would watch, bemused by how I could be late when she’d already squeezed a thousand and one things into her morning. As a family, we are always late. My mum doesn’t own a watch.

‘I’m going,’ I said, hoping someone might notice the hurt in my voice.

But my mum and dad were already taking their seats at the little wooden table.

The humourless man in the suit was a lawyer. To him I didn’t exist, a waste of time billed in five-minute increments. As I made my way to the door, my dad gave me a quick surreptitious wave, like displays of affection were no longer allowed.

Now, in the oppressive magnificence of the Chelsea High corridor, I was faced with another man in a suit. This one was older, wearing what looked like a cape over his black jacket and a white bow tie. Even the masters had a uniform here. He came nearer, stopping right in front of me. He unfolded his arms, pushed back his cape and put his hands in the pockets of his suit trousers. ‘Name?’ he said.

‘Norah Whittaker, Sir,’ I said, palms sweaty. I’d never called anyone Sir in my life, but nervousness made it roll off my tongue. At my old school we called the teachers by their first names, and half of them were our neighbours. ‘I’m –’ I saw his eyes squint as he processed the information.

‘Whittaker.’ His voice whistled on the W. ‘Well, well. We’ve been expecting you, haven’t we, Ms Whittaker?’ There was the whistle again. ‘Not the best first impression.’ He looked at his watch. ‘Late on your first day.’

I shook my head. ‘No, Sir,’ I said. ‘Sorry, Sir.’

He tilted his head like he was trying to get the measure of me. ‘Your father was always late,’ he said in the end. ‘Shows a sloppiness of character. Wouldn’t you agree?’

I swallowed, unable to reply. The reference to my father had caught me off guard.

For the whole of my life, Mulberry Island had been our home. The life my parents had led before they owned the boat was never mentioned. They talked only of life on the island – the river, the land, the community was ingrained in our blood. But just over a week ago I had learned the truth.

It still felt unreal. I had discovered, amidst the chaos – in hurried, snatched conversations – that my parents weren’t native islanders. In fact, my dad had gone to this school; to Chelsea High. It was where he had met my mother. They had been rich. Were rich. Might be rich. I didn’t know. His parents, the grandparents I’d been told were dead, were definitely rich, though. Very rich. It was them paying for the humourless lawyer who had arrived on our boat this morning. They were paying for everything. They were the reason our colourful old boat was now moored at one of the most exclusive docks in London, surrounded by stark grey floating palaces like sharks circling to eat us alive.

‘Look at me when I’m talking to you, Ms Whittaker!’

My eyes shot back to his. I could see them, watery and angry.

‘I warned them to steer well clear of you lot. Trouble. Always have been,’ he sneered.

‘Let’s leave it there, shall we, Mr Watts?’ A woman had swept up next to him, black pantsuit, cropped black hair, big pearl studs in her ears. ‘I think Ms Whittaker understands the importance of timekeeping. Am I right?’

I nodded, a lump forming in my throat. It all suddenly felt too much, too overwhelming. If this woman (whoever she was) had hugged me at that point, I would have gladly hugged her back. But this wasn’t Reception class. There would be no hugs.

Mr Watts straightened up. He folded his arms again, pursed his lips and said, ‘Late again, Ms Whittaker, and it will be detention.’ He gave a curt nod to Mrs Pearce before striding away.

Putting her hand on my shoulder, Mrs Pearce ushered me down the dusky corridor. Our footsteps echoed. There were closed classroom doors on one side of us and big windows with mottled glass and a view out to an elaborate courtyard on the other.

‘Don’t worry too much about Mr Watts,’ I heard her say softly. She was still facing ahead, as if what she was saying wasn’t quite by the book.

With the threat of tears welling in my eyes, I didn’t look her way. I focused on her shoes instead: Gucci loafers that clipped on the polished wood.

‘I think he might have been . . . shall we say, a disgruntled class mate of your father’s,’ Mrs Pearce went on.

I looked up at her then, frowning.

She smiled, her kind eyes crinkling. ‘He had quite a reputation here, your dad. On a sunny day it’s still possible to make out where he wrote his name in weedkiller on the cricket pitch on the last day of term. An interesting choice, wouldn’t you say? Writing one’s own name rather gives the culprit away.’ Mrs Pearce seemed to have the measure of my dad in an instant. ‘A loveable fool’ my mum always called him. ‘A bloody idiot’ seemed to be the kindest name currently on people’s lips.

As we walked beside walls lined with oil paintings of past masters and gold-leafed boards listing the well-known names of old alumni, I tried to imagine Dad as a boy walking these same corridors, but it was too hard to visualise. Instead I thought about him sitting on the bench in the patch of scrubland we’d called a garden, next to our old mooring, dressed in his jeans and favourite shirt with hair swept to one side, an image of his usual self – except for his eyes, which that day weren’t smiling.

‘Come and sit down, Nellie Norah.’ He’d patted the seat next to him. ‘There’s something I need to talk to you about.’

My immediate fear was that someone had died. That was the expression on his face. But no one had died. Except as he spoke, it felt like a death. A death of us, of what we had, of the life I knew and thought I would always know.

‘The thing is, Norah,’ he’d said, rubbing his chin, awkward, nervous, not quite able to look me in the eye. ‘The thing is . . . I’ve made a little mistake. Well, actually, quite a big mistake.’ He’d paused, glancing down at the weeds around our bench. ‘The film company. All the financing. It was a scam, Norah. The McGinty brothers are not quite as honest as they seemed.’

I frowned, not understanding. ‘It can’t be a scam,’ I said. ‘We made a film. Everyone on the island invested in us.’

I remembered the party we’d held when we reached the financing target. My dad, grinning from ear to ear, thwacking Jess’s dad on the back. ‘We’re gonna double your money, Keith, you just wait and see. ‘And Jess’s dad holding up his crossed fingers with a nervous smile. ‘It’s everything I’ve got, Bill. Look after it.’ As we sat on the bench, I saw the lines and wrinkles of my dad’s downcast face.

‘They’re going to give the money back, right?’ I said.

He didn’t reply. Just sat up and stretched his arms along the back of the bench, as if he hadn’t heard the question.

We sat side by side in silence. I kicked a dandelion with my foot. There are moments, I’ve realised, when you know your life is about to change, when everything around you gets much brighter, bigger, clearer. Right then I could see each individual petal of the dandelion, dazzling yellow, as big as a sunflower.

Mrs Pearce stopped at a polished wooden door. She seemed to steel herself for a second before pushing it open. Inside we were met with a wall of noise and laughter.

I stood, dumbfounded. If the entrance to Chelsea High was Victorian Gothic, then this was the Apple Store. The classroom was a gleaming cube of white, stripped back to stark white walls and achingly contemporary art. The pale grey floor gleamed like an ice rink. The light fittings were huge translucent orbs, and the windows had automatic blinds that responded to sunlight. People were everywhere, like ants. Phones were being passed around, music thumped, girls sniggered and swished their gleaming hair, boys lolled, kicking their feet against the expensive furniture. There was no compass-carved graffiti on manky old desks here, or hockey balls being chucked millimetres from the swanky art.

‘Here we are,’ Mrs Pearce said, ushering me into the mêlée. She clapped her hands together and shouted, ‘OK, everyone, settle down. Settle down! Music off, phones away!’

Chairs scraped and bashed and huddles dispersed with lazy insouciance.

I looked around for a place to sit, but my eyes were distracted. All I could see was wealth – the labels on the bags, the top-of-the-range phones and iPads chucked on every smart white table, even the diamond studs in earlobes and the flawless make-up – sparking in me a shameful, envious insecurity. And then I noticed the people looking at me, the assessing glances. My cheeks began to pink.

Mrs Pearce was unwrapping her own iPad from a turquoise-leather pouch. ‘OK, everyone, this is Norah,’ she said, glancing from her emails to the class to me. ‘She is joining us this year, so I hope you will all be your delightful selves and make her feel welcome. Freddie, feet off the desk, for Christ’s sake. You’re not in kindergarten.’

I stared at the scrutinising, disinterested faces in front of me. Aware of my hair, my skin, my bag, my shoes. Wishing I had put more thought into every item I was wearing. But of course my thoughts had been elsewhere.

‘There’s a spare seat at the back, Norah.’ Mrs Pearce gestured vaguely to where the glossy brunette I’d seen earlier was leaning against the window sill, watching my progress. Her fingers thrummed on the table that belonged to Freddie, the boy with jaw-length black hair who’d had his feet on the desk.

I willed my feet not to trip as I walked across the shiny floor, trying to ignore the stares. As I put my bag down on the empty table, I reminded myself that this was temporary. Once the lawyer had sorted it all out, we’d be turning our boat round and chugging back to Mulberry Island. These people, this place was just a blip on my life’s horizon. I could probably get through this without even having to talk to anyone.

The brunette was still watching me with narrowed eyes.

Then suddenly I was forgotten, as the door was thrown open and Coco Summers stalked into the room.

‘Sorry I’m late, Mrs Pearce!’ she called, breezing across the classroom in a cloud of blonde with her eyes glued to something on her phone. Without even pausing to register the fact I was standing by the desk getting my stuff out, she sat down in my seat.

I stood, not quite knowing what to do. My diary and biro were out on the table already. Coco had chucked her phone into her silver rucksack on the floor, her legs stretched out in front of her. It was only as she ruffled fingers through her blunt fringe and gave the room a cursory glance that she acknowledged me.

‘Yes?’ she said.

‘I was . . .’ I glanced at my things on the table, then to the front. Mrs Pearce was typing on her iPad, words appearing on the whiteboard screen behind her. I swallowed, pointing to the seat, wishing this wasn’t happening. ‘I was told to sit here.’ Coco shook her head with a dismissive frown. ‘I sit here.’

Mrs Pearce looked up. ‘Oh, Coco,’ she sighed, hands on her hips.

Coco looked bemused. ‘I always sit here. You know that, Mrs Pearce.’

Mrs Pearce rubbed her forehead, then gave a half-smile. Coco grinned, wide and confident.

‘Norah, if you could just find somewhere else for the moment, that would be great,’ said Mrs Pearce. She peered around the room. ‘There’s one over there.’

In the corner was a spare double desk.

‘I’m sorry, you’ll be on your own,’ Mrs Pearce said.

‘It’s fine,’ I muttered, scooping up my things, wishing that had been where I’d sat in the first place. Anything not to have drawn attention to myself.

Mrs Pearce watched me until I sat down and got myself ready. I didn’t have an iPad. I had a notepad and an old chewed biro. I didn’t even have a phone. My mum had confiscated it after reading a message thread over my shoulder. Surely these girls have something better to do! she’d said, as the messages laid into me and my family, full of vitriol about the damage my dad had done and the shame I should feel.

The worst part had been when my friends had joined in. People I’d always assumed would give us the benefit of the doubt. My mum hadn’t wanted me infected by the news stories either. Like the time she threw away the bathroom scales – better not to know, she’d said. But I’d seen enough already. The camera crews, the so-called friends of my dad who had sold stories to the paper. I told myself they were just doing it for the money. When you’ve lost everything, sometimes your principles have to go too.